Backstage on election night, sometime around 11:30 p.m., Rob Russo collapsed.

It happened before the results were final, but after it had already become obvious that his boss, Hillary Clinton, would not be the next president. He was with three friends from the campaign, waiting for senior aides to arrive in the staff hold room at the Jacob Javits Center. In the crowd, excitement turned to anxiety, then to shock, then to tears. “The air just got sucked out of the whole place,” Russo says. “It was silent. Nobody was saying anything to anyone.”

When he got up, “it sort of became a dream. I felt detached from it, from everything.”

What happened next is still a dim blur. He remembers leaving around 4 a.m., because he took a cab, “which I never do.” He remembers dressing in black the next morning — a dark gray “H” T-shirt, a black cardigan, his only pair of black pants — because he has worn black clothes almost every day since. And he remembers the somnambulant trek back to headquarters in Brooklyn, because the whole staff was there wandering around the office — suddenly without direction for the first time in years.

Russo started packing up his desk. “I didn’t know what else to do,” he says. “It was very unclear to us all what we should be doing.”

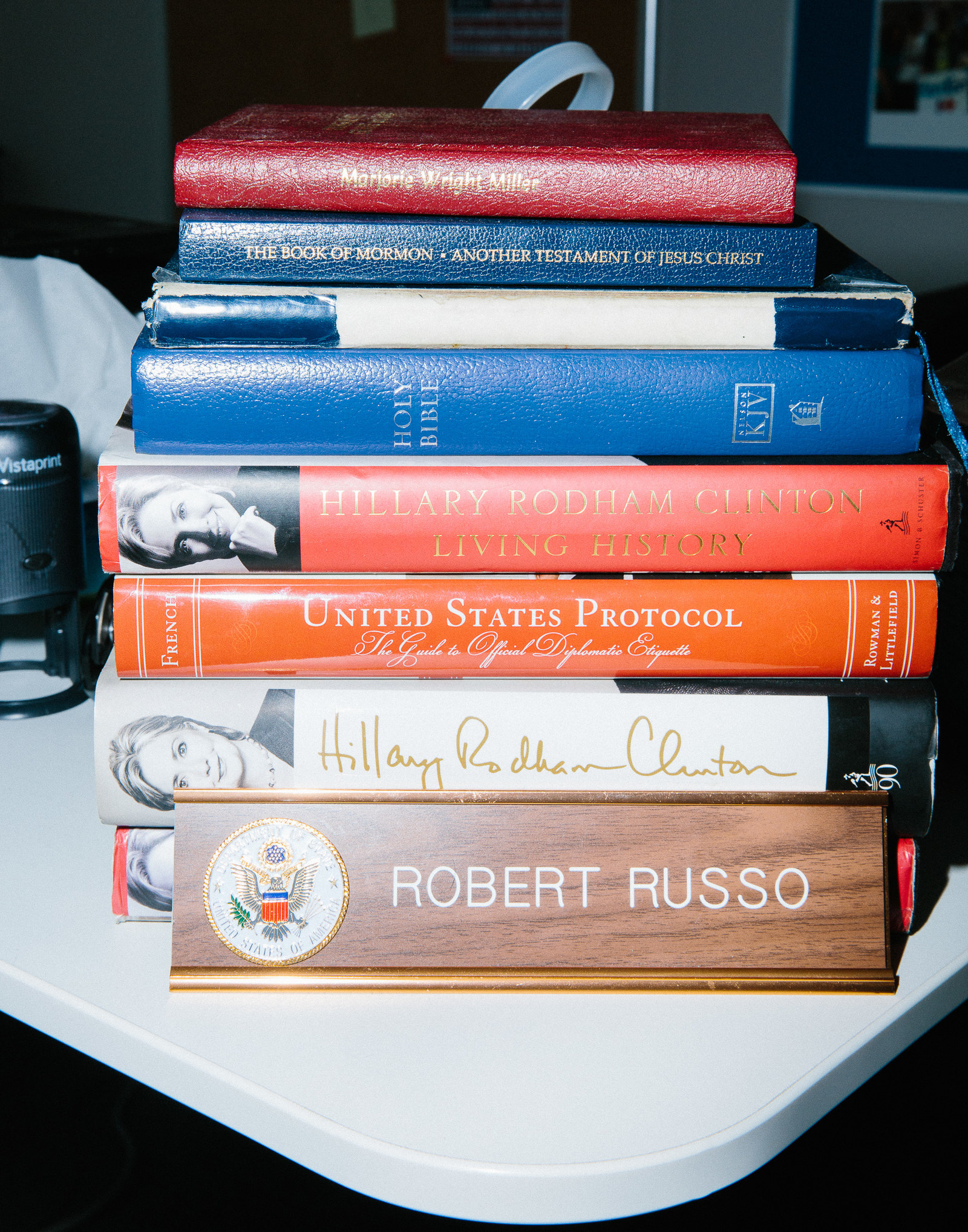

This was a new sensation for the 30-year-old director of correspondence and briefings. Russo has spent more than a decade managing Clinton’s “paper process,” a job he approaches with extreme diligence and care and order. He compiles her briefing books, handles her mail, and drafts letters to every corner of the vast and layered network known as Clintonworld: thank-yous, condolences, graduations, and weddings. Maybe you’ve seen some of the them, the letters from Clinton that pop up on staffers’ Instagram feeds or in news stories about the friends and voters who have received them. Clinton is the sender, but each note is also the product of a long-worked-out system that this aide steers.

Russo, slim with a small swept-back pompadour and a neatly trimmed beard, has made a decade-long study of Clinton’s paper process — aka “her paper,” aka “the flow of paper” — passing every draft to his boss in shared “To Sign”/“To Read” folders, then internalizing each one of her edits until writing in “her voice” became something close to “second nature.”

He could show you any one of the 110,000 letters he has drafted since 2008, because he keeps them scanned and alphabetized in a folder on his computer. He could tell you that Clinton’s personal stationery was once cream-colored, with her name at the top in blue, but that now the paper is white with a blue border. He could tell you that for most of her life, she signed her name without looping the “y” in “Hillary,” but that after her first presidential campaign eight years ago, a small almond-shaped sliver suddenly appeared at the base of the “y.” (He would also note, however, that in letters from the ’70s and ’80s, “every once and awhile she does loop the ‘y.’”) And he could tell you that, for about nine years, every letter has been written in Poor Richard, a squat typeface with tiny curled serifs, originally used in Poor Richard’s Almanac, because at some point in 2008, a letter from a friend arrived and Clinton exclaimed, “I love that font,” sending her executive assistant on a hunt to identify it.

Over the years, Russo has developed his own Clinton-themed style and usage guide, governed by a few simple rules for both the letters (“consistent use of the Oxford comma”) and the briefing book (bio photos should be an inch and a half wide, 2 inches tall, closely cropped to the face, high resolution, but not too big of a file). At the State Department, he learned that letters should be more formal. No contractions, for instance. (“It was ‘I am delighted,’” not “‘I’m delighted.’”) And fewer flourishes, which he realized early on when a draft came back with the word “fabulous” crossed out. (“Let’s try to tone down some of the adjectives,” Clinton suggested to him.) He has followed her from the State Department to her personal office in Manhattan to the campaign in Brooklyn, tasked along the way with drafting letters to diplomats and voters from rope lines in Iowa. On the campaign, he managed a staff of 10 people, sorting every email submitted to the website and overseeing every briefing book, for not only Clinton, but also for 10 of her top surrogates. He had anxiety dreams about categorizing emails. He lost 15 pounds from the stress.

By Election Day, there was one thing left to do: send the final three-ring binder and set of tabs, prepared to his precise specifications, to Clinton’s suite at the Peninsula Hotel, where aides would fill it with transition materials — her first briefing book as president-elect.

Interviews with Russo over the last three years — before, during, and after the campaign — depict a career spent producing the materials that, as he describes it, “neatly catalog the experience” of Hillary Clinton’s life. So he was not prepared, a few days after the blow of November 8, for the letters that started showing up in P.O. Box 5256, the one listed on Clinton’s website. They came by the hundreds, then thousands, most from people his boss had never met — all about the loss.

Russo put off the writing as long as he could. “Because I didn’t — I didn’t know where to begin,” he says. “I didn’t know what to say.”

Few living people know what it’s like to run for president and lose. It is a singular kind of defeat — a personal, disorienting rejection, delivered overnight at the hands of the American people, thrusting the candidate, her voters and her campaign, however many decades in the making, into the political wilderness of Wednesday morning.

On the night of his loss in 1992, President George H.W. Bush described it in a short diary entry, made at 12:15 a.m.: “The election is over — it’s come and gone. It’s hard to describe the emotions of something like this... But it’s hurt, hurt, hurt and I guess it’s the pride, too.” He was “absolutely convinced,” he said, that his campaign would defy the polls and pundits, “but I was wrong and they were right and that hurts a lot.”

“Now into bed, prepared to face tomorrow.”

For Hillary Clinton, the weeks after November 8 played out in private. After 18 months of non-stop campaign coverage, she appeared now only in flashes. There were the Facebook and Instagram posts from neighbors who passed her on wooded walking paths in Westchester, the videos of standing ovations at Broadway shows. And there was the photo, circulated on Twitter, of Clinton eating breakfast at a resort in upstate New York, seated alone, no makeup, scrolling through her iPhone, nails painted the sort of dark shade she never wore as a candidate.

What has remained out of public view are the letters that come into P.O. Box 5256. Rob Russo has spent the six months since Election Day reading, sorting, and answering each one — a job still months from completion — as the staff around him has dwindled steadily to the small cadre of aides who preceded the campaign, working once again out of Clinton’s old personal office in Midtown Manhattan.

The space is clean and nondescript and more or less what you’d expect of a big office building above a Bobby Van’s Grill on 45th Street: the shaded glass entryway, the reception desk, the hallway of gray carpet, the line of adjacent offices. And then, you see the mail room. Piles of white corrugated postal bins sit in stacks of five and six across from Russo’s office, spilling out of the room, into the hallway, filled with packages and envelopes of different shapes, sizes, colors — all waiting for a response.

Forty-eight hours after Election Day, Clinton started emailing Russo again, forwarding him messages to print or save for a response, as per the routine they’d developed over the years. (“I’m here to help,” Russo told her in one reply. “And she responded, ‘You always are. And that means so much to me.’”) When it came to the letters, Clinton had little instruction for what should be said, but one absolute directive for what should be done: “She is insistent that every message should get a response,” he says.

Their process is the same as before: the Oxford commas, the alphabetized PDFs. But handling Clinton’s paper is a job that has also been fundamentally altered by that night in the Javits Center. Every letter Clinton receives now reflects the loss. They come from friends and political figures, from academics offering an analysis of the race. The vast majority come from members of the public: people who want to say something to Clinton, to vent or to tell her a story or to give advice.

Since Election Day, about 100,000 letters have arrived — two times the amount that Clinton received during the 18-month campaign, according to Russo. People send art. Kids send drawings. One person sent a Thanksgiving turkey, which was thrown away upon discovery. (“I don’t know if it was cooked,” Russo notes.) About a month after the election, Russo had to rent a U-Haul to pick up 50 boxes from the post office. “We’re still digging through stuff from December and January.”

When he first started reading the letters, Russo was surprised. “They’re incredibly personal. They’re incredibly well-crafted,” he says, sitting in the office of Clinton’s longtime spokesman, Nick Merrill. “I’ve been so blown away by the eloquence of the American people in the aftermath of this campaign. The quality of the writing...I mean, we still get casual ‘I’m a fan!’ or ‘I love you!’ Short things. But we get so many that are beautifully written — like people really sat down and took time to write something,” he says. “It’s probably draft three.” One day this spring, as if to provide an example, Russo pulled out an unopened letter at random from one of the bins. It was three pages, handwritten. The ending read, I hope you know it’s OK to cry. We won’t tell anyone.

Most of the letters are like that: positive, gentle. It’s a big change from the campaign, when the aides tasked with reading online submissions to Clinton’s website would have to take breaks during the day because the hate mail was so “coarse and horrifying,” Russo says. “That was their job. We responded in batches to as much as we could. But to read the stuff that people would write would be so hateful, it was… just imagine Twitter, or like the comments section of a news article, where people become so unhinged, and so mean, and so personal.”

Now, a lot of the letters start the same way: “Some version of, ‘I’ve started writing this five times. I finally sat down to do it.’ Or, ‘I’ve been putting this off for months.’”

What people have said next hits every note on the emotional spectrum. Some are “just angry” about Donald Trump. Some apologize to her. Older women in particular “offer some sort of regret,” Russo says. “Like, ‘For 20 years now, I’ve watched you just be dragged in the public, and I’m sorry that happened.’ And those from younger generations often tell Clinton that the election set off a new “political awakening.”

Clinton’s own future, a subject addressed in many of the letters, has drawn debate among Democrats, some of whom would like to see the former candidate, her husband, and their unwieldy universe of political allies recede quietly into the background of American politics, clearing the way for a new generation of leaders in the party. Her first post-election project, an effort launched earlier this month to fund and support activists and organizers on the left, was met with division among progressives.

"Where are you?" they ask.

Even admirers who write to Clinton are split on the question. In one camp, people say she should assume a “global platform,” embrace a status more historic than partisan, away from “day-to-day politics,” Russo says, recounting the letters they’ve received. “It’s a little more common than I even expected, that particular spin on it: ‘Don’t run for office, don’t even necessarily get involved in domestic politics in any way. ... You’ve now earned this position of respect around the world that you should use.’

“And then there are other people who say ‘I miss you.’ That’s pretty common. ‘I miss you. You were a part of my life for two years, and now you’re gone. You were on my TV every night. You were in my news every day. And I miss you, and I want you to be back.’ You know?” Those letters take two forms. The first, infused with the same shock that sent Russo to the floor on the night of November 8, demand that Clinton come back. “Where are you?” they ask. “You need to be giving speeches. You need to be standing up to Donald Trump. You need to be in the news every day. You need to be out there.” The second form: “We’re here for you whenever your time is ready…” “You’ve earned the right to do whatever you want.” If there is a third strain, it’s the people who simply encourage her: “Don’t think that it wasn’t worth it, that it didn’t mean anything to people.”

Russo attaches many of the original letters to the drafts he passes to Clinton, “and she reads them all.” She isn’t deeply involved with each one — there are too many for that, Russo says — but she checks in frequently on his progress. “She wants to make sure we’re doing it.”

“You know, the secretary said this to me herself: that so much of what we receive — like that” — Russo points to the bins of mail across the hall — “for so many people is catharsis.”

“It’s like they have so much to say. And there’s no one they can say it to.”

A few days before Thanksgiving, Russo sat down to write.

He started with the language in Clinton’s concession speeches, using key passages as his “baseline” — a loose boilerplate for answering each letter. The drafts are forward-looking — always with some note about keeping up the fight — but in many cases, particularly in letters to friends, there are reminders of what has ended for Clinton. Short, stark phrases: “This is hard,” “These weeks have been difficult.” Clinton hasn’t once cut or softened the lines. “I’ve been very blunt in my writing,” Russo says.

Some days, reading and responding to the letters still piled high in Clinton’s Midtown office, Russo is “brought to the brink of tears,” he says. “Some days, yeah, it completely chews me up.” Others, “despite the fact that I live in this” — in work that now revolves again and again around the loss — “I don’t really think about it.”

“It’s just what I do every day.”

It was August 2005, his freshman year at George Washington University, the first week of classes, when he first signed up to volunteer in her Senate campaign office. He was 18, shy with longer hair, from Lido Beach, a small town on the South Shore of Long Island. That semester, three or four times a week, he stuffed envelopes at a big table in the volunteer room on K Street. When he learned that it had been the Clintons’ dining room table in Arkansas, he was stunned. “That was my real entry into her world.”

After interning for Clinton during the 2008 primary, Russo was hired and tasked with drafting thank-you notes to thousands of the campaign’s top supporters. He worked with the political team to come up with a list of people, hung a large map on the wall and worked from state to state (first New York, then Arkansas, then in alphabetical order), crossing each state out in red when complete. The “Thank You Project,” as it became known internally, ended with a total of 16,054 letters. Most were sent electronically, but some, about 6,000, Russo did by hand, working with Clinton to add a more “personal touch,” tailored to each individual.

That summer introduced Russo to the vast landscape of people who have followed the Clintons through three decades at the highest levels of American politics: friends and advisers, current aides and former aides, donors, fundraisers, old colleagues — a shifting topography of people, with its own “eras” and phases and worlds within “the world.”

Every letter Clinton receives now reflects the loss.

The makeup of their extended network has been a subject of fascination and scrutiny for almost as long as Bill and Hillary themselves. Often, it seems, the story of the Clintons cannot be told without a supporting cast: “Hillaryland,” “FOBs” (Friends of Bill), staffers who become the story (Sidney Blumenthal, Doug Band), unsavory ties to donors, and warring internal factions. In 2013, the New York Times Magazine mapped Clintonworld as a solar system of 133 people scattered across planets like “Arkansas Pals” and “2008 Victims.” In 2015, the Washington Post valued it as a $3 billion enterprise.

Bill Clinton, who does not use email, also has his own dedicated correspondence team. Other members of his extended network have taken on an unofficial role in its care and maintenance. In Arkansas, a woman named Lynda Dixon has maintained “Lynda’s List,” a sort of informal newsletter updating members of the Clinton network on recent happenings and deaths. Last year, on the campaign, Clinton also hired a “director of engagement,” De’Ara Balenger, who, among other duties, had the job of keeping old friends in the loop, in line, and happy. Critics might attribute these efforts to a fixation with maintaining a political network that has helped power four combined presidential campaigns and a sprawling foundation. Others would say it’s simply a reflex that plays out personally as well as politically, sometimes to a comical degree. (The former president, an adviser said, recently spent the better part of an afternoon fine-tuning his response to a letter from a fourth-grader.)

Russo, meanwhile, describes his work as a practice in “the discipline of gratitude.” The phrase is one of Clinton’s favorites from the early ’90s, borrowed from the Jesuit priest Henri Nouwen. It’s the idea that gratitude should be practiced almost like an exercise or academic pursuit, something you commit to and work at. “That’s sort of her whole mantra in terms of her correspondence,” he says.

What began in 2005 as a something closer to a casual extracurricular — “I thought, Sure, I’ve always loved Hillary Clinton...Why not?” — quickly deepened into a cause. Russo has adopted her mantras as his own, worked on her behalf with quiet and steadfast rigor, and subscribed wholly, as he puts it, to her “unerring belief in the power” of every thank-you letter. He is what you’d call a true believer, without agenda. When he sees a phrase she’s used for decades (“God-given potential” is one), “it’s like home base.” When he worked full-time at the State Department while also earning his law degree at night, he kept himself going by recalling the inscription of a plaque on Clinton’s desk: “Never, never, never give up.” On jogs, when he’d feel the need to stop or slow down, “I’d think, You know what, Hillary Clinton would keep running. So I literally would keep running.” He has taken his post-2016 commitment to a black wardrobe just as seriously, buying more black clothes after the election, even changing his Facebook avatar to a black square.

Russo, diligent and meticulous in that diligence, is aware that his work ethic borders at times on the ridiculous. (If he has to be out for a wedding, a colleague joked, “He’ll email and be like, I’ll be at the dinner for 1 hour and 46 minutes.”) Around age 5, he memorized the names and order of the US presidents from a placemat in his house. Before college, he mapped out a course plan in an Excel spreadsheet that would allow him to graduate in three years, five classes per semester, plus summer courses. He followed it to the letter, while also volunteering and then interning for Clinton, founding the GW chapter of “Students for Hillary,” and acting in a play every semester. (Theater, second to Clinton, is his passion. In 2016, his contribution to a fill-in-the-blank campaign exercise was “‘Theatre-going Oxford comma enthusiasts with good hair’ for H.”)

For all his actual, rare proximity to Clinton, Russo still regards his boss and her world with the reverence and humility of the 18-year-old amazed to have a seat at her dining room table. “I would never deign to say that I'm a member of the Hillaryland,” he said in an interview before the start of the campaign, when he was one of fewer than 10 people working for Clinton. “If others want to say I'm a member, that's great. I would never say so myself.” And although he will admit now that he has achieved a sort of “mind-meld” with Clinton after 10 years of handling her paper, he is quick to qualify any such assessment as “a charitable view.” (“Not to draw the parallel,” he’ll say, “but…”)

He treats his entry into Hillaryland as a series of sacred memories, still preserved in sharp, perfect detail. He can describe the Senate office hallway where, as a new intern, he froze mid-stride like “a deer in headlights” after crossing paths for the first time with Clinton; the way she glanced at him, headset on, “probably to acknowledge the idiot that was just staring at her”; and the feeling of the last day of that internship, when he handed back his badge and stood outside the Russell Senate Office Building, “tears streaming down my face,” crushed that it was over, never imagining that he would not only work for Clinton’s 2008 campaign, but also follow her to the State Department and back to New York as one of her most trusted staffers — the point of connection between Hillary Clinton and an entire universe of people, personal and political, all moving together through the last decade.

For Russo, all of it, in a way, had been leading to the start of the 2016 election — to the “excitement” and “relief,” as he once described it a few months into the campaign, of the moment he was able to draft a letter with the words, “I am running for president.”

This phase of his work, he knows, is now something of the past.

In November, a few days after he started writing, Russo went home for Thanksgiving on Long Island. He was in the den, playing with his 4-year-old niece, when suddenly she looked up at him sweetly and said, “Donald Trump is our president. But next time, I’m going to help Hillary run faster.” Oh god, Russo thought, looking back at her, unable to explain.

About a week later, on November 29, Russo packed up his apartment near the Brooklyn Heights campaign office and moved to the West Village. The next day, he and the small group of aides still working for Clinton returned to her old personal office waiting on 45th Street. “We had to get out of Brooklyn,” he says on a recent spring afternoon, the mail still piled high across the hall. “It was too much to face.”

There are reminders of the loss across the office: the old campaign posters; the bins of letters waiting for replies; Russo still in black. (His button-down on this particular day is dark gray, “so I’m cheating.” His undershirt, he notes, is black.) The atmosphere, though, is not dark. “It’s funny,” offers Merrill, Clinton’s press secretary, now 10 years into his tenure on staff. “This place does not make me sad. At all... Our daily lives are not depressing.”

“Those of us who remain are incredibly fortunate to be here,” Russo says, “but feel a sense of wanting to have that continuity.” That word — continuity — is one you hear often from those still working in Clinton’s personal office. It was the same way when she became secretary of state after 2008, Russo says, “for her to have people around her who have been around her, supporting her — and I feel that way now that we are sort of in that transition period.”

Russo is only 30. He has a law degree, has passed the bar. Despite what he describes as an ongoing “mourning” phase, the director of correspondence and briefings is in no hurry to leave or move on to another phase of his career.

“I’m not gonna lie and say that I haven’t thought about the future. Of course I have,” he says. But when he thinks about his options, “I’m having a hard time getting excited about the idea of anything else,” finding something “as rewarding and exciting and relevant.” For the time being, Russo admits, “the answer is that maybe there is nothing.”

“Not to be maudlin about it all, but something died. And something broke. And so much of what people write addresses that."

The reason he stays, however new and uncertain Clinton’s place in national politics may be, isn’t just the “tremendous sense of loyalty.” It’s “the mission” behind his work, he says. That mission has changed now in essential ways since the first summer he spent writing thank-you letters in 2008, moving state by state across a map.

One afternoon in the fall of 2014, on the cusp of his second presidential campaign with his boss, Russo described the project in straightforward terms, saying that Clinton wanted to a) take the time to thank the people who helped her campaign, and b) give them something to remember it by — a letter to keep or frame or pass down in the family. “A piece of history,” he said back then. “It was about creating something tangible. A campaign is intangible. It’s a memory, it’s fleeting, it’s ephemeral.” When it ends, “you don’t have anything to latch onto.”

On the other side of 2016, as Clinton transitions out of electoral politics, handling her paper has come to mean something else, something more intangible. Russo is helping shepherd a new phase, one that “does feel a little uncertain, because for so long it has been about electoral politics,” he says. “There are people for whom I am their connector to Hillary Clinton. That’s something that I take very seriously. They’re someone’s relationships.”

This is true for friends and longtime supporters — people she’s known since before the 1970s, he says. And it is true for the members of the public — people who write to Clinton to say that they’ve followed her since before 1992, that they saw her at this event or that convention.

There’s a whole lifespan that America has had with Hillary Clinton as a political candidate, and for all the things that entailed — for admirers, for detractors, and for Russo — it has ended.

“Not to be maudlin about it all, but something died. And something broke. And so much of what people write addresses that. And in a way,” he says, “I think in what we’ve written, we’ve addressed that.”

“There’s so much more that she’s going to do. But it will be different. It will absolutely be different.” ●