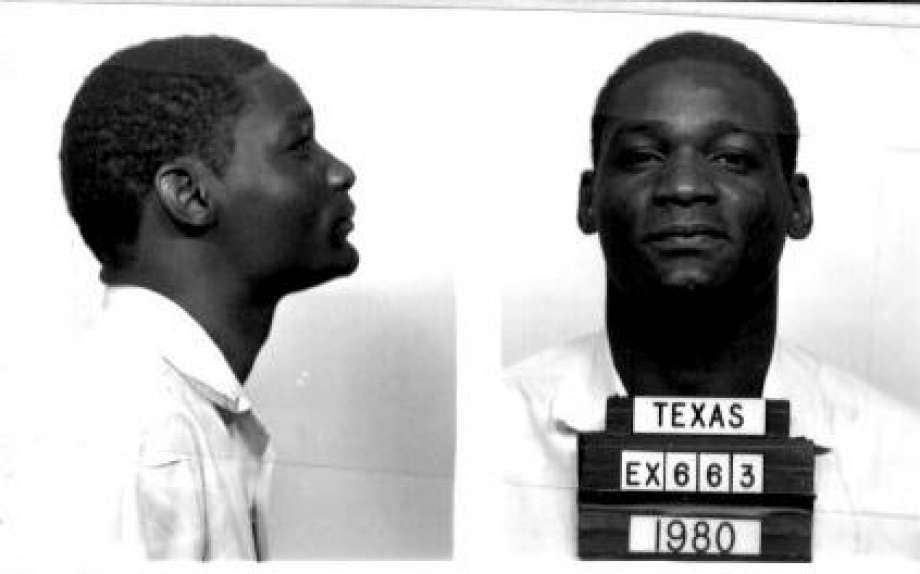

In April 1980, 20-year-old Bobby James Moore and two other men attempted to rob the Birdsall Super Market in Houston. Moore carried a shotgun, and one of his accomplices had a pistol. As an accomplice opened a bag to fill with money, Moore, wearing a wig and sunglasses, pointed his gun at two store clerks. When one of the clerks shouted, Moore shot the other in the head, killing him instantly.

Moore has been on death row for 36 years. His guilt is not in question, but his lawyers say he does not have the mental capacity to justify executing him for his crime.

In 2002, the Supreme Court ruled that executing someone with an intellectual disability is a “cruel and unusual punishment,” prohibited by the Eighth Amendment. Now, in the court’s new term, Moore’s case will require the justices to consider how to define intellectual disability.

Psychologists typically diagnose intellectual disability with tests of a person’s IQ and “adaptive behavior,” meaning the interpersonal and practical skills needed for everyday life. The tests examine a broad range of abilities, including whether the person can clothe and feed themselves, handle money, read and write, and whether they are gullible and easily led. But in Moore’s case, the state of Texas instead relied in part on a stereotype based — literally — on a tragic character from John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men.

Leading medical and scientific organizations claim that Texas conjured up this bizarre literary standard to prevent people on death row from being deemed to have a disability. But 16 other states that use the death penalty have lined up in support of Texas, arguing that this issue should not be ceded to “a small professional elite” — that is, doctors and scientists specializing in intellectual disability — who may be motivated by their opposition to the death penalty.

The stakes are high, and not only because Texas — responsible for more than 40% of the 841 executions in the United States since 2000 — has the most active death row in the nation.

“There are other states that deviate from the clinical consensus of what intellectual disability is,” John Blume, a legal scholar who heads the Cornell Death Penalty Project, told BuzzFeed News. So if the court takes a firm line on how adaptive behavior should be measured, the decision could reverberate beyond the Lone Star State, forcing all states to align their assessments with scientific standards.

This isn’t the first time that the Supreme Court has been asked to define intellectual disability. In 2014, in an opinion written by Justice Anthony Kennedy, the court ruled that Florida was wrong to use a rigid cutoff of 70 IQ points or less. Today’s IQ tests, which are set so that 100 points is the average score, have a measurement error of three points or more. This means that any score should be considered as a range, not an absolute value. After that court decision, Florida reduced the sentence of convicted killer Freddie Lee Hall, who had scored 71 on one IQ test, from death to life in prison.

Moore’s case is expected to hinge not on IQ, but on the trickier measures of adaptive behavior. Although standardized tests for adaptive behavior give scores similar to IQ, they are not always used, and different states measure adaptive behavior in different ways.

In 2004, when ruling on the case of José García Briseño, convicted of murdering a sheriff, the Texas Court of Criminal Appeals took inspiration from a character in Of Mice and Men: Lennie Small, a lumbering migrant worker who understands neither the world around him nor his own strength, and ends up killing a woman who flirts with him.

“Most Texas citizens might agree that Steinbeck’s Lennie should, by virtue of his lack of reasoning ability and adaptive skills, be exempt,” Judge Cathy Cochran wrote in her opinion. But she questioned whether the scientific definitions of “mental retardation” should apply to the death penalty.

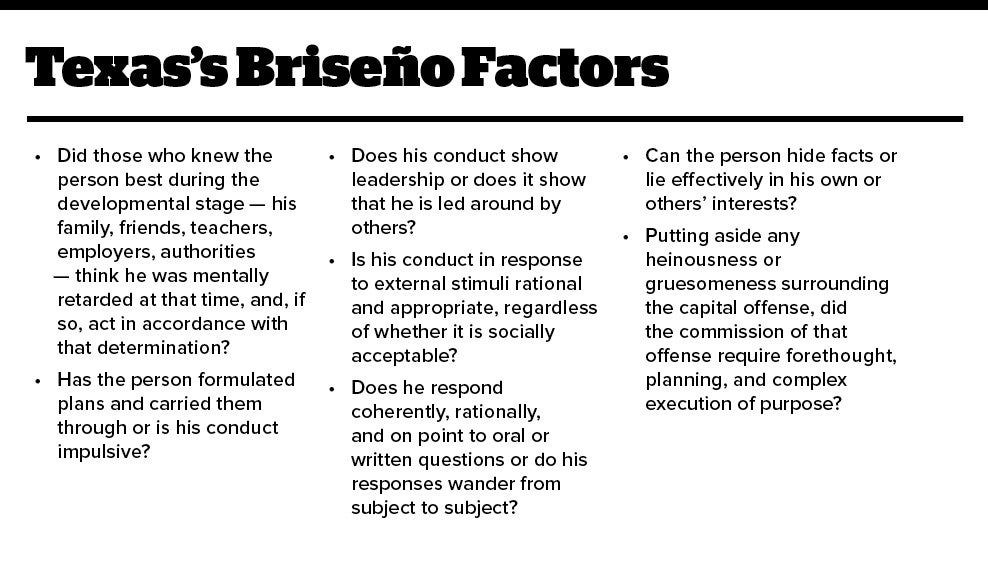

Calling the measurement of adaptive behavior “exceedingly subjective,” Cochran proposed seven questions, now called the “Briseño factors,” to help judge whether a convicted killer has the intellectual capacity to justify facing the death penalty. She did not specify exactly how they should be used.

The Briseño factors use specific abilities — such as whether the person can lie, and whether their crime required planning — to judge whether someone has a disability, rather than assessing every aspect of their adaptive behavior. Experts say the Briseño factors do not reflect modern clinical standards of disability.

“It’s not how adaptive behavior is measured by anyone, anywhere, and it sets an unreasonable standard,” Margaret Nygren, executive director of the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities (AAIDD), told BuzzFeed News.

One big problem, Nygren added, is that the Briseño factors turn the diagnosis of intellectual disability into a series of trade-offs, in which behavioral deficits are countered by abilities such as a facility for lying.

“It’s absolutely normal for people with intellectual disability to have strengths and weaknesses,” she said. “Those don’t balance each other out.”

In a brief submitted to the Supreme Court in the Moore case, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton downplayed the importance of the Briseño factors, describing them as “entirely optional” considerations.

Still, the brief stresses specific abilities that the state’s forensic psychologist, Kristi Compton, noted when she examined Moore in 2014, including that he “played pool for money, and mowed lawns.” Her report also argued that Moore’s decisions to wear a wig when robbing the store, to conceal his gun in a plastic bag, and to flee to Louisiana, where he was later arrested, showed that he was capable of “abstract thought.”

According to Blume, several other states — including Alabama, where death-penalty sentencing has faced a wider constitutional challenge — similarly focus on convicted killers’ abilities, rather than their behavioral impairment, when judging whether they are eligible for the death penalty.

Researchers also worry that the Briseño factors, based on a fictional character with a severe disability, don’t represent the reality of intellectual disability on death row.

“They’re driven by stereotypes and misconceptions,” Marc Tassé, a clinical psychologist at Ohio State University in Columbus, told BuzzFeed News. “There is no Lennie in real life.”

In fact, most people who have successfully challenged their death sentences with disability claims have more subtle intellectual impairments. “They’re generally in the mild range,” Keith Widaman, a specialist in intellectual disability at the University of California, Riverside, told BuzzFeed News. “A lot of them are identified for the first time when they interact with the criminal justice system.”

“There is no Lennie in real life.”

Between the 2002 Supreme Court ruling and the end of 2013, 147 cases in which death row inmates claimed they had an intellectual disability were decided in court on their merits, according to a study led by Blume. The average IQ score of the 81 inmates who succeeded in overturning their death sentence was 68 — just two points lower than the generally accepted threshold for “normal” intelligence.

Similarly, when a case hinges on adaptive behavior, the inmate is usually near the boundary of “normal,” and so may not fit a stereotypic view of a person with a disability.

“There is a strong impulse to conjure up our own image of what people with intellectual disability are like, and then to evaluate individuals by how closely they seem to resemble that preconceived image of ‘a mentally retarded person,’” argues a brief submitted to the Supreme Court in the Moore case by the AAIDD.

Rather than falling back on stereotypes, scientists argue that adaptive behavior should be assessed using validated tests, such as the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales and the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System (ABAS). These tests consist of structured interviews in which someone who knows the person well, such as a parent or caregiver, is asked a series of questions about their specific abilities, such as counting change, following a work schedule, or wiping up after spilling a drink.

On an ABAS test, a score of 0 means the subject cannot perform the skill, 1 means they almost never perform it, 2 means they can sometimes perform it, and 3 means they always or almost always do. ABAS divides adaptive behavior into three domains — conceptual skills including reading and numeracy, social skills, and practical living skills — and makes a diagnosis of impairment if the person falls outside the normal range for any one of the three.

Moore was never tested with either the Vineland or the ABAS scales. In her 2014 assessment, Compton, the Texas forensic psychologist, administered another test, called the Texas Functional Living Scale, that is often used to judge whether people with dementia need help with daily living. Although Moore scored outside of the normal range, Compton concluded that his score was “not an accurate reflection of his abilities” because Moore lacked experience with two of the tasks — operating a microwave oven and writing a check.

While the Vineland and ABAS tests are considered the current gold standard for assessing adaptive behavior, Tassé says they have one drawback when it comes to death-penalty cases: These tests were designed to assess the full range of abilities across the entire population, rather than to make precise distinctions at the border between normal and impaired behavior. Tassé and Widaman are finalizing a new test, called the Diagnostic Adaptive Behavior Scale, to give better assessments near this threshold.

The fact that the science of measuring adaptive behavior is still a work in progress helps explain why 16 other death-penalty states are supporting Texas in the Moore case. In their brief, submitted by the attorney general of Arizona, these states argue that they shouldn't have to amend their rules every time a scientific body publishes new diagnostic guidelines.

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) — which, with other professional bodies, has filed a brief supporting Moore — overhauled its diagnostic manual. One of the changes was to replace “mental retardation,” which judged the condition’s severity by IQ test scores, with a diagnosis of intellectual disability focusing mainly on adaptive behavior. That brought the APA’s definition broadly into line with the AAIDD’s — which was last overhauled in 2010. Yet just four states have specifically adopted either organization’s latest diagnostic guidelines in death-penalty cases.

In its brief, Texas noted that Moore himself denied that he had an intellectual disability in the penalty phase of his retrial in 2001, a year before the Supreme Court ruled that intellectual disability should protect a convicted killer from execution.

Some inmates say they would rather be executed than called “retarded.”

But Tassé, who has testified as an expert witness for about 20 death-row inmates (not including Moore), has found that some still say they would rather be executed than called “retarded.” The stigma against intellectual disability is particularly powerful in prison, Tassé said, because of threats of violence from other inmates: “If you’re weak or perceived as weak, you’ll be victimized.”

When the Supreme Court hears arguments on the Moore case on Nov. 29, the justices are expected to get conflicting accounts of Moore’s trajectory to murderer. Texas’s brief depicts him as a street-smart drug abuser whose mental abilities reflected his failure to regularly attend school, rather than a disability. “He financed his drug habit with proceeds from stealing cars, burglarizing houses, and hustling pool,” the brief says.

The brief submitted by Moore’s lawyers, in contrast, describes his struggles to keep up at school, an abusive father who called him “stupid,” and an incident when 12-year-old Moore was hit in the head with a chain and a brick during violent protests against the racial integration of Texas’s schools.

Whatever the justices make of Moore’s life story, in the end they must rule on whether Texas has adopted a definition of intellectual disability that allows unconstitutional executions.

In the 2014 Florida case, the court ruled that the state’s failure to treat IQ scores as a range “disregards established medical practice.” But legal experts are unsure whether the court will be similarly aggressive about the trickier measurements of adaptive behavior.

“I’m skeptical that they’re going to say the Briseño factors are OK,” Cornell’s Blume said. “But how much they’re going to wade in beyond that remains to be seen.”