NEW YORK CITY — The Supreme Court ruled Tuesday that states cannot limit the bar on executions of persons with intellectual disabilities to those with an IQ of 70 or below.

Although the ruling was on a Florida law, it could have consequences for states across the country that have adopted similar IQ-based standards for determining whether a person's intellectual disability precludes use of the death penalty.

Twelve years ago, the court ruled that the Constitution bars the execution of those with intellectual disabilities. On Tuesday, the court considered "how intellectual disability must be defined" in order to meet that standard — deciding 5-4 that Florida's bright-line threshold rule is unconstitutional.

Justice Anthony Kennedy — writing for himself and Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan — examined the "the framework followed by psychiatrists and other professionals in diagnosing intellectual disability," including professional understanding of the standard error of measurement, or SEM, which reflects fluctuations in IQ scores.

In accordance with that, the court found that "the vast majority of States" rejected such a "strict 70 cutoff" and found a "trend toward recognizing" the SEM, which Kennedy wrote is "a reflection of the inherent imprecision of the test itself." The rejection and trend, Kennedy wrote, are "strong evidence of consensus that our society does not regard this strict cutoff as proper or humane."

Concluding — and relevant in other states — he wrote, "The flaws in Florida's law are the result of the inherent error in IQ tests themselves. An IQ score is an approximation, not a final and infallible assessment of intellectual functioning." As such, Florida's bright-line rule that those with an IQ above 70 could not show other evidence of intellectual disability, the court ruled, is unconstitutional.

Justice Samuel Alito, dissenting from the court's decision, was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts and Justices Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas.

They differed from the majority on several points, including the court's understanding of the 2002 case, Atkins v. Virginia, as well as the court's reliance on what Alito called "positions adopted by private professional associations" and the court's assessment of what states' laws and any "trend" might be.

Kennedy, in his ruling, had found that "at most nine States mandate a strict IQ score cutoff at 70" — including Florida, Kentucky, Virginia, and Alabama, as well as, possibly, Arizona, Delaware, Kansas, North Carolina, and Washington. "Thus in 41 States an individual in Hall's position — an individual with an IQ score of 71 — would not be deemed automatically eligible for the death penalty," he wrote.

Alito found the court's reliance on those states that have no death penalty punishment to be inappropriate here because "[t]he fact that a State has abolished the death penalty says nothing about how that State would resolve the evidentiary problem of identifying defendants who are intellectually disabled." He also found there to be no evidence to show that any "trend" exists regarding SEM being considered by states.

Because of all this, Alito wrote, "[T]he resolution of this case should be straightforward: Just as there was no methodological consensus among the States at the time of Atkins, there is no such consensus today. And in the absence of such a consensus, we have no basis for holding that Florida's method contravenes our society's standards of decency."

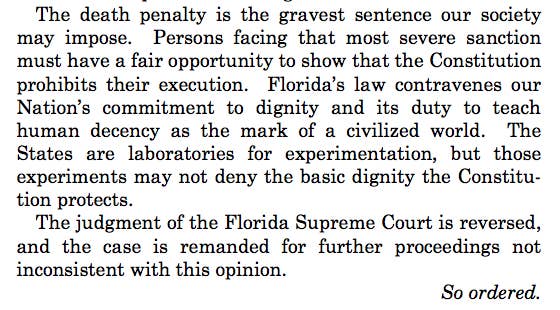

The Supreme Court's conclusion, written by Justice Anthony Kennedy: