Helping straight white men look less fascist was the last thing I thought I’d be doing when I started cutting hair at a queer-owned salon in Park Slope, Brooklyn, back in 2014.

But November 8, 2016, changed everything, and not long after Election Day one of my clients came in for a trim. Connor could go months between visits, and it was a surprise to see him come back sooner than expected, asking for an adjustment to his cut. At a dinner with his wife and friends, he explained, he’d been told he looked like “one of the Breitbart guys.”

Two weeks earlier, I had given Connor an undercut. Although he didn’t ask for the cut by name, it fit the description of what he wanted: a low-maintenance, easy-to-groom style that made him look handsome. But the undercut has a backstory — and parts of that story were becoming increasingly visible as white supremacists celebrated what they considered a breakout political triumph.

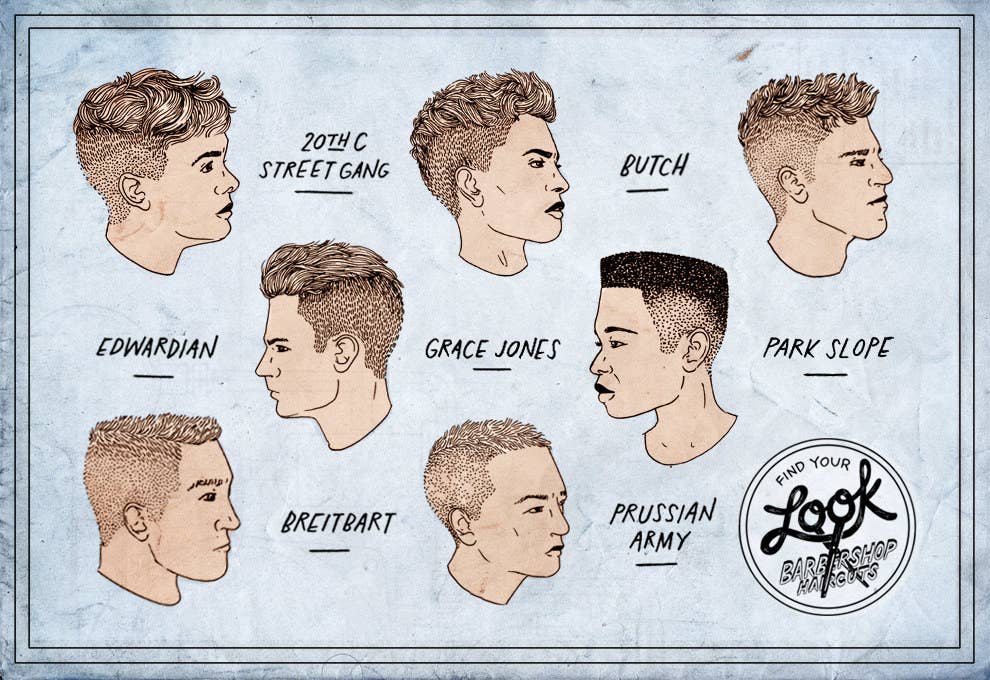

We love our race, the alt-right began to loudly proclaim. They also love their undercuts — the “fashy” look, as fascists like to call it. But many others have loved the undercut before them.

When the undercut grew popular in the German empire ruled by Prussian kings in the late 1800s, it was known as der Inselhaarschnitt — the island cut, in reference to the patch of hair sitting atop a shaved head. English street gangs, like the Peaky Blinders in Birmingham, were soon wearing the same style, and it made it to the United States on the heads of working-class European immigrants.

As Hitler’s Third Reich rose to power, its members embraced the undercut as a way to connect with the military success of the Prussian armies that came before them. Later, it became popular in the US Armed Forces, but in the wake of World War II it became associated with wartime violence, and European men chose looser, short hairstyles to counter the military connection.

It resurfaced in black barbershops, where fades and military cuts transformed into edgy sharp styles. The hi-top fade emerged in part out of the undercut in those barbershops during the 1980s and early '90s, wrote Quincy Mills in Cutting along the Color Line: Black Barbers and Barber Shops in America, and was most popularized by the coolest of the cool, Grace Jones.

"Nobody has been immune to the trauma of 2017."

What’s fascinating is how one haircut has signified so many different things, across different historical moments and different constituencies. As a queer stylist, it’s a cut I saw in militaristic homoerotic photography in the 1990s and fashion magazines in the 2000s. It’s a cut I’ve given many times at Badlands, the salon where I work. It has been part of the aesthetic language in the queer community for years, put to particularly good use by people identifying themselves as she or the nonbinary they/them. The cut is androgynous and sharp, and can be used in many different ways. It can pull long hair away from femininity without going into masculinity.

But with its new profile as the chosen cut of the white nationalists, it’s causing some white men to rethink a cut that has long been in the mainstream of hipsterdom. It means that the aesthetics of the racist alt-right made their way into my salon in one of the US's most liberal enclaves.

Which isn’t that surprising, because nobody has been immune to the trauma of 2017. It played out in my cutting chair just as it did in bars and office blocks and everywhere else where Americans behold our current moment. The government is in the hands of racists, anti-gay and anti-trans bigots, misogynists, predators, and opportunists, and I’ve seen the results. Connor’s wish to avoid bumping up against a specific brand of maleness and whiteness was one of many ways I saw the political climate articulated as I wielded my scissors and razors.

"What may seem like a simple conversation about a snip, trim, chop, fade, shave, or layer often has a lot more substance to it."

The transitions that take place in a hair salon can be very powerful. In Connor’s case, the election made him want to distance himself from what he saw as a fascist alliance. I also saw it as a shifting perspective for Connor — from what he is seeing to how he is seen, both personally and politically. Changing your hair for political or even religious purposes is not new. Many communities and individuals have changed their hair when their community, identity, or values has come under attack. Shaved heads, natural hair, and short hair have all been used as a language to express politics and values.

In that context, what may seem like a simple conversation about a snip, trim, chop, fade, shave, or layer often has a lot more substance to it. At our salon, we work hard to embrace our queer community and make a space where everybody is friendly and nobody tolerates hate. I’ve found comfort sharing personal stories with my clients this year, and sharing their moments of change while cutting their hair.

After the Orlando massacre, one of my clients, a teacher, teared up in my chair because no one mentioned the tragedy at work. He felt isolated and alone with his grief, and said he felt comfort on the way to his cut, knowing he was going to a place where the queer flag hung in the window.

That same week, another client came in, and we talked about how androgynous haircuts help articulate a person’s transition from a feminine to a masculine appearance. I loved that they were choosing very specifically what articulated their identity, and that I could be of service not only to their "look" but their evolution.

Personally, I cut the sides of my hair short and leave the back long — which to my happy surprise made me more visibly queer and more in line with the women I was attracted to. It also led to a friend suggesting that I should let my hair grow out before leaving on an upcoming trip to a country where being a lesbian is still illegal. ●

Patty Suarez is a New York based artist and barber, working at Badlands Salon and Barbershop in Brooklyn. On Instagram she is @mrjulianray.