The day after America elected Donald Trump as president, Emin Gün Sirer, a computer science professor at Cornell University, received three emails from prospective graduate students. They were hoping to be admitted to Cornell, they wrote, but were foreign nationals. Should they be worried about the outcome of the election?

Sirer, who moved from Turkey in 1989 to Princeton University as a student himself, wrote back: Absolutely not. Any serious threats by Trump to block highly skilled foreign immigrants would be opposed by technology companies, he reckoned — immigrants are, after all, a key part of the scientific enterprise in the US. (As of 2013, 18% of the 29 million scientists and engineers living in the US were immigrants.)

But like many university leaders, Sirer is concerned that the president-elect’s anti-immigration campaign legacy, as well as his tone of intolerance to minority groups of all stripes, will repel students and scientists from other countries who flock to the US for study and work.

“There are many other European nations who are chomping at the bit to get at the flow of young bright minds,” Sirer told BuzzFeed News. “These processes are slow, they will outlast any president — a decade from now we may find ourselves falling behind in critical fields.”

Since Trump was elected, university leaders have been circulating letters that tacitly or explicitly condemn the exclusionary tone adopted by the incoming administration during the campaign — an attempt to quell the fears of minority groups on campus, as well as the thousands of foreign nationals who are part of those communities.

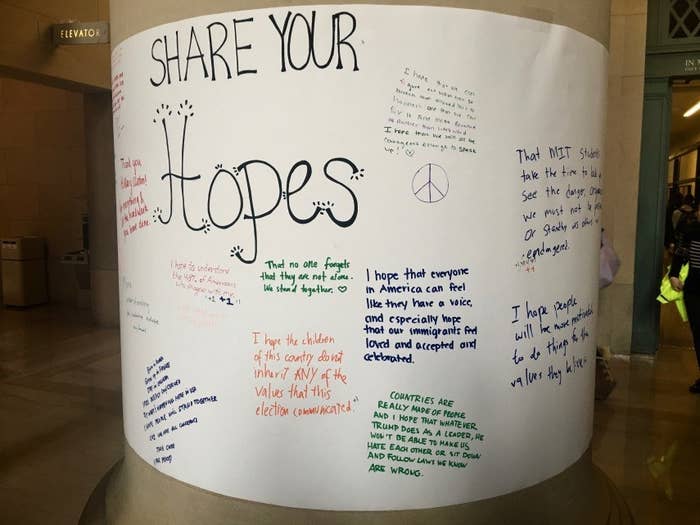

At MIT, where 65% of postdoctoral researchers and 43% of the graduate community are foreign nationals and potential immigrants, students papered the pillars inside the lobby of Building 7, in the heart of campus, and publicly shared their “hopes” and “fears” following the election.

On Thursday, MIT president Rafael Reif wrote to all students and faculty that “a new administration in Washington that promises a great deal of change,” but added that those shifts “will not change the values and the mission that unite us.” He noted the university’s commitment to tackling clean energy and climate change — two issues that the new administration is expected to underfund or ignore.

In the closing months of her Rhodes Scholarship at Oxford University, anthropologist Jess Auerbach found herself choosing between PhD programs in the US and the UK.

“I wanted to be somewhere that was forward-looking and on the cutting edge,” Auerbach, a South African citizen, told BuzzFeed News. She chose Stanford University for its well-funded research program, and moved to Palo Alto in 2010.

Auerbach is now set to graduate in December. She kicked her job search outside the US into high gear when she realized Trump was running an earnest campaign. Part of her concern was the anti-science rhetoric of the campaign, and particularly Trump calling climate change a “hoax.”

She also recoiled from the divisive tone of a campaign that pledged to end immigration and ban Muslims. Following the election, she feels validated in her choice to leave the US for a faculty position at a college in Mauritius, an island country in the Indian Ocean.

“There is a sense of relief, but a sense of relief mixed with grief,” she said. “There is somebody elected to president that can destroy a lot of that ecosystem” that wooed her to the US, she said.

Perhaps mindful of losing top talent like Auerbach, on Thursday the Stanford faculty senate passed a new resolution stating that the university was committed to “an open and inclusive community that embraces all members, irrespective of race, ethnicity, religion, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, citizenship, abilities and political views, and that celebrates and learns from diversity.”

Heidy Khlaaf, who is a US citizen but grew up in Egypt and Florida, moved to the UK for graduate school because she wanted to escape the racism and sexism that she had experienced growing up in Jacksonville as an Arab with an accent.

After the Brexit vote, which also espoused an anti-immigrant position, she considered returning to the US to work, after completing a PhD in computer science.

But the results of Tuesday’s election changed her mind about returning to work in the US. “He preached a message of hate, specially towards Muslims, specially towards Arabs,” she said of Trump.

But Khlaaf also recognized the dilemma she is now in: “The hatred seems to be in both countries, so I guess it doesn’t matter where I live.”

Like many scientists, Carnegie Mellon University associate professor of computer science Jean Yang is panicked that the new administration will underfund science and roll back progress.

But as a recent immigrant who moved to Pittsburgh from China in 1991, she told BuzzFeed News, she’s as worried about racism. “A big concern for me about where to do science involves being in a country where I feel like I don't feel racial discrimination,” she said. “I'm worried that this won't be the case anymore in the US.”

At CMU, 62% of the graduate student population and 13% of faculty and postdocs are foreign visitors to the US. The day after the election, Andrew Moore, the dean of the School of Computer Science, sent an email to the department underscoring his commitment to inclusion.

“This is basically Starfleet Academy for computer science,” he wrote. “We don't merely embrace the mix of domestic and international computer scientists here...it defines us.”