One afternoon in October, a skinny 6-year-old boy in navy Crocs plodded into a nondescript Tampa clinic clutching a stuffed monkey. His mom followed him in with a big bag of toys.

Like an estimated 70% of kids with autism, Luke was a picky eater who had been battling an achy tummy, a yeast infection, and chronic constipation for years. He had tried antibiotics, gluten- and sugar-free diets, and therapy. Nothing worked. So now his mom, Julie, was about to try a last-ditch procedure.

Luke lay on his side on a cushioned exam table while his mom held his arms and kept him from squirming. A clinic technician plunged a syringe into a box next to the sink, pulled up a small volume of a brown, smoothie-like liquid — human feces — and pushed it into his colon through a catheter tube.

Luke scrunched his legs together, and Julie soothed him: “Good job, buddy.”

Five minutes later, Luke was off the table and back to his energetic self, playing with a Toby the Tram Engine, chewing on a rubber toy, squatting on the floor, and slinking out into the hallway when his mom’s back was turned.

For Julie, this was a rare moment of relief. This infusion of “healthy” bacteria from someone else’s poop could heal Luke’s gut, she hoped, and maybe even spur him to speak a full sentence for the first time.

“I'm happy we're at this point where we can actually do this,” she said later that afternoon. “I think it's going to help us quite a bit.”

A spate of studies over the last decade have convinced microbiologists and doctors that “fecal microbiota transplantation,” or FMT, works for at least one disease: a deadly bacterial infection in the gut known as Clostridium difficile, or C. diff. No one knows whether the procedures work on other conditions, though dozens of clinical trials are testing them on people with irritable bowel syndrome, Crohn's disease, obesity, diabetes, epilepsy, autism, and even HIV.

The science is advancing rapidly, with more and more scientists excited about the potential and potency of fecal matter and the microbes in it. The FDA regulations on these procedures, however, keep them out of reach for most patients: Since 2013, the agency has banned doctors from doing fecal transplants on anything except C. diff.

It’s difficult, and perhaps futile, to control a “drug” that’s so abundant, free, and 100% natural.

This rogue clinic in Tampa has found ways around the rules. Although the FDA could technically shut it down, hit it with fees, or even pursue criminal prosecution, the clinic has decided it's worth the risk. So far, an FDA spokesperson told BuzzFeed News, it “has not taken action to date against any clinic or doctor.”

Even some critics of poop clinics are sympathetic to the FDA’s plight: It’s difficult, after all, and perhaps futile, to control a “drug” that’s so abundant, free, and 100% natural. Experts estimate that tens of thousands of people worldwide have already figured out how to get access to the treatment, and are eagerly sharing the information with others online.

In a YouTube video that has been viewed 92,000 times, for example, a mom with a blender in her bathroom demonstrates how she prepared a transplant sample, using her own poop, for her daughter. In private Facebook groups, people solicit samples from young donors, and trade tips about battling side effects and diet swings. One Reddit user, LuckyJenny, shared that their wife “reported having a Dunkin' Donuts medium latte and a double chocolate donut prior to donating ‘the specimen.’”

Raphael Lataster, a theology student at the University of Sydney and a member of one of the Facebook groups, told BuzzFeed News that he’d spent more than $7,000 getting 10 transplants at a clinic in Sydney. The good news was that he’d been feeling leaner and fitter since the transplants. The bad news was that it had not fixed the problem he was hoping to solve: “I was desperate to be cured of my dandruff.”

Many doctors and scientists, however, are wary of these experimental procedures, seeing them as a money-making racket for any condition other than C. diff. No one knows the long-term effects of co-opting someone else’s bacteria. It could well be dangerous: Poop from an unscreened stranger could carry serious infections, like hepatitis or gonorrhea, or dormant viruses.

“If you start having a lot of this craziness,” said Colleen Kelly, a gastroenterologist and assistant professor of medicine at Brown University, “something's going to happen to a patient, or there will be some infection transmission or some bad outcome and that's going to really delegitimize the real value to this treatment.”

Ever since Luke was a newborn, he often refused to eat, and was consistently underweight. Julie felt like she was failing her fundamental responsibility as a mother. “It was just very hard for me that he didn’t eat,” she said.

Just before Luke turned 1, Julie and her husband moved from Maryland to Tampa. Julie struggled to find a support system, and the right kind of medical help. Once, when she asked a speech therapist if Luke might have a swallowing problem, the doctor turned her focus from Luke to his mother. “They told me to take a feeding class,” Julie said. She was crushed, and felt chastised.

The family lived by Tampa Bay, and Luke enjoyed feeding the ducks. One of his first words, at about 18 months, was “quack.” He didn’t say many more.

He was also fiercely stubborn: He wouldn’t eat a banana unless Julie gave it to him whole. At the Gymboree play area, when the Gymbo puppet was put away, the toddler would cry without reprieve. By the time he was 2, he had stopped making eye contact.

Julie and her husband put Luke in speech therapy, but avoided getting an evaluation for autism. Julie couldn’t fathom the idea that her son might never talk. “Autism was very scary for me,” she said. “It was terrifying.” They eventually got a diagnosis in 2012, before Luke turned 3.

That’s about when he began getting intense bouts of constipation, often going a week or even 10 days without a bowel movement. At a National Autism Association conference in St. Petersburg in 2014, Julie met Scott Smith, a local physician assistant who suspected that Luke had a yeast infection. Smith’s tests later confirmed an abundance of Clostridium bacteria in the toddler’s gut, along with yeast.

Julie felt a wave of guilt for not catching it sooner, or finding a doctor who could. But she was also relieved that finally, someone understood the struggles she faced with Luke.

Julie first heard about fecal transplants from her friend Bonnie, who had a young daughter with autism and had also consulted with Smith. Bonnie had considered fecal transplants for her daughter, but ultimately didn’t try them. She did give the little girl antibiotics and antifungal medications. After a few months taking these drugs, the girl started talking — a transformation that Julie later watched, astonished, on a video recording Bonnie sent her.

Maybe Luke’s autism, Julie thought, was connected to the bacteria in his gut.

Gastroenterologist Roland David Shepard sees patients at the Tampa clinic where Luke got his first fecal transplant. The tidy, one-story building sits on quiet, leafy street, with an acupuncturist on one side and an allergy clinic on the other. Shepard’s is among a handful of clinics in the US where anyone curious about poop transplants can get walked through the procedure, even if they don’t have C. diff.

Shepard, who also sees patients for routine colonoscopies and general GI queries, estimates that he’s done a few hundred fecal transplants since 2010, when he tried it for the first time at a patient’s request.

“This has been the most rewarding part of my practice,” he said one afternoon in October, leaning against the exam table in an empty room. “Some of the people who come in are gray — they look like skeletons. If you see them again a month later they’re totally different people, with a smile on their face. It doesn’t take too many of those to see why we do this.”

Shepard usually sees four or five cases of C. diff every week. He will initially consult with these patients in the clinic, but fecal transplants happen at one of two endoscopy centers in Tampa, set up to do colonoscopies under anesthesia. He drives there with the freshly made sample stashed in a cooler in the back seat.

For patients with any other illness, however, those centers won’t do fecal transplants, complying with FDA rules. So Shepard and his team will show new patients, like Luke’s mom, how to do an ever-so-slightly modified version of the procedure themselves, without anesthesia or colonoscopy, and sell them prepared poop samples. Then the patients go home and repeat the procedure, typically buying fresh supplies every month.

Shepard argues that this is not a transplant, but a “tutorial” or “instructional infusion,” and therefore does not violate FDA rules. (Patients entering the clinic sign a form affirming that they, assisted by the doctor or staff, will “self-administer” the procedure.) “The main thing is that we’re teaching, behind the door, we’re teaching,” Shepard said.

His clinic is owned by Florida Medical Clinic, a company that runs multiple medical facilities near Tampa. But because of concerns over the regulatory gray zone, Shepard said, he bills his transplant work through a Florida LLC, RDS Infusions, that is separate from Florida Medical Clinic.

A colonoscopy for patients with C. diff is $675, plus fees to the endoscopy center, and three office tutorial sessions cost about $1,000. Shepard said that these rates just about cover the costs of testing donors, buying equipment, and paying his staff for the work. Last year’s revenue was “above a break even point, but it wasn’t much over that,” Shepard said. And if the price is too high for a family, he said, he sometimes does the procedures for free.

(The CEO of Florida Medical Clinic, Joe Delatorre, confirmed through his executive assistant that he is “aware and supportive of Dr. Shepard’s Fecal Transplant program, and this program is conducted separate from FMC.”)

A handful of other clinics in the US are willing to help patients get fecal transplants, but take a more conservative approach. The Bright Medicine Clinic in Portland, Oregon, for example, offers “counseling” for patients with irritable bowel diseases who want to try the procedure on their own at home. It’s a way to lower the risk for patients who are determined to try it anyway, the clinic founder said.

“There are all kinds of crazy stories of people who are doing FMTs at home with unscreened stool or animal stool, using material that may not help them in any way,” Mark Davis, a licensed naturopath who built the Bright Medicine Clinic practice in Portland and now practices in Maryland, told BuzzFeed News.

Davis believes that, for many patients, the benefit of these procedures outweighs the risks. So he will screen poop donors for medical conditions, he said, and has drawn up a hygienic protocol for DIYers who want to try it at home in the safest way possible.

Scientists and doctors know quite a bit about the effect of fecal transplants on gut woes like Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. But other conditions are less understood. Although there are links between gut bacteria and psychiatric disorders, for example, no one knows for sure whether fecal transplants will reliably offer relief.

There’s been one published study of poop transplants for autism.

There’s only been one published study of poop transplants for autism, out this January, involving just 18 children with an autism diagnosis and gut problems. Half the group received prepared fecal samples orally, mixed in juice or milk, thrice a day over two days; the other half had the transplant by enema. Then they all drank a more dilute mixture once every day for eight weeks. The groups were then monitored for two months.

By the end of the study, most of the kids had fewer digestive symptoms like constipation and indigestion, and most also showed improvements in their communication and social behaviors. The study found no adverse effects related to the fecal transplants.

“We saw that it was remarkably safe,” said James Adams, who heads the autism research program at Arizona State University and led the study. Still, the trial was small, and the treatment was not compared to a placebo.

Despite the dearth of evidence, Shepard has no doubt that poop transplants help kids with autism. He said he has seen between 100 and 200 cases of autism, and heard from many parents that fecal transplants do wonders for digestive symptoms.

Has he seen the changes in children himself? “Oh, absolutely,” he said. Patients kept ordering prepared samples — they wouldn’t be doing so, he figured, if it didn’t work.

There is perhaps no one who understands the growing demand for poop better than Catherine Duff. The 61-year-old mother of three is a transplant veteran.

“When I had to do my own with my husband, there weren’t any videos on YouTube,” she said, recounting her ordeal over cinnamon rolls at a café in the Virginia suburbs.

Duff did her first transplant in 2012, when she was dying from the bacterium Clostridium difficile, her seventh infection in as many years. She was in constant pain, could rarely keep meals down, and was bedridden from incessant diarrhea.

Her daughter Caroline, a lawyer, stumbled across a Grey’s Anatomy clip that described fecal transplants. She printed out a few studies on transplants she found online, along with a protocol a DIYer had posted, and offered the pages to her mom’s doctors at the hospital, begging them to try it. When they refused, Duff went home, figuring she didn’t have much to lose. Her husband had his stool tested for infections, and a few weeks later, lying on her bed with the bottom elevated on risers, she received a homemade enema with a slurry of his poop.

Within a day, she recalled, she was out of bed and joining her husband for a meal at the table. The chronic diarrhea and pain vanished, and her energy returned. Her rebound was so successful that when she contracted C. diff again, six months later, she was able to persuade a doctor to do a fecal transplant at the hospital.

She couldn’t stop thinking about the thousands of other C. diff patients who couldn’t get a transplant — “this easy, low-risk way to save their lives.” So she founded a nonprofit, the Fecal Transplant Foundation, to advocate for patients who were having trouble convincing doctors to do the procedure. She also started a private Facebook group for people contacting her with questions.

At first, Duff only heard from people infected with C. diff. But over the years, she received more and more queries from patients with conditions that are not typically associated with the gut.

“The science seemed to really explode,” Duff said. In the past few years, scientists have linked the trillions of bugs in our digestive tissues — the gut “microbiome” — to everything from autism to cancer to depression.

Now everybody has heard of the microbiome, and lots of sick people are wondering whether their problem could be gut bacteria. Every day, Duff fields dozens of phone calls, emails, and texts from strangers asking which doctor she recommends for the procedure, where they can find equipment online, or what they should do about their father-in-law’s trouble with gas.

She responds to as many as she can, though has grown increasingly worried about some of the things these DIYers have tried putting in their colons.

“People are doing kefir enemas!”

“It’s like a wild west: ‘I’m gonna use my 4-year-old’s [poop], I’m gonna get my dog’s poop,’” Duff said. Breast milk, goat milk, kimchee, coffee, pickle juice. “People are doing kefir enemas!”

Duff’s Facebook group hovers at just over 1,000 members. Most of the posts ask about members’ transplant experiences, like how quickly they found relief, or if anyone had experienced a certain side effect. Sometimes people make specific requests: Someone wanted poop samples near Santa Fe, a woman with chronic fatigue was looking in Seattle, and a Las Vegas resident wanted poop gluten-free. Sometimes members simply announce that they are about to try the procedure, as a call for moral support. Duff tries to remind everybody that donors need to be tested for infections first. And she does her best to prevent people from passing on amateur medical advice.

Duff is troubled by the fact that, partly because of the FDA’s restrictions, wealthy people are far more likely to gain access to the procedure. They can fly to clinics in Argentina, the Bahamas, the UK, or Australia. But people who rely on medical insurance aren’t likely to coverage for the experimental procedure — even if they are C. diff patients who can convince a doctor to do it.

“One woman in one of these groups, her car has been repo'ed, her TV has been repo'ed, all because of C. diff,” Duff said. “And now she is having trouble arranging for rides just getting to her appointments.”

Because of her own experience, Duff empathizes with those resorting to repurposed kitchen tools and poop donated by strangers. “Unless you can get into the clinical trials for some of these other conditions, people really have no choice,” she said.

She has mixed feelings about the Tampa clinic and others like it. She doesn’t like the idea of skirting medical regulations, but knows better than anyone that it’s the only way for most people to access the treatment. “I try to be Switzerland on that,” she said.

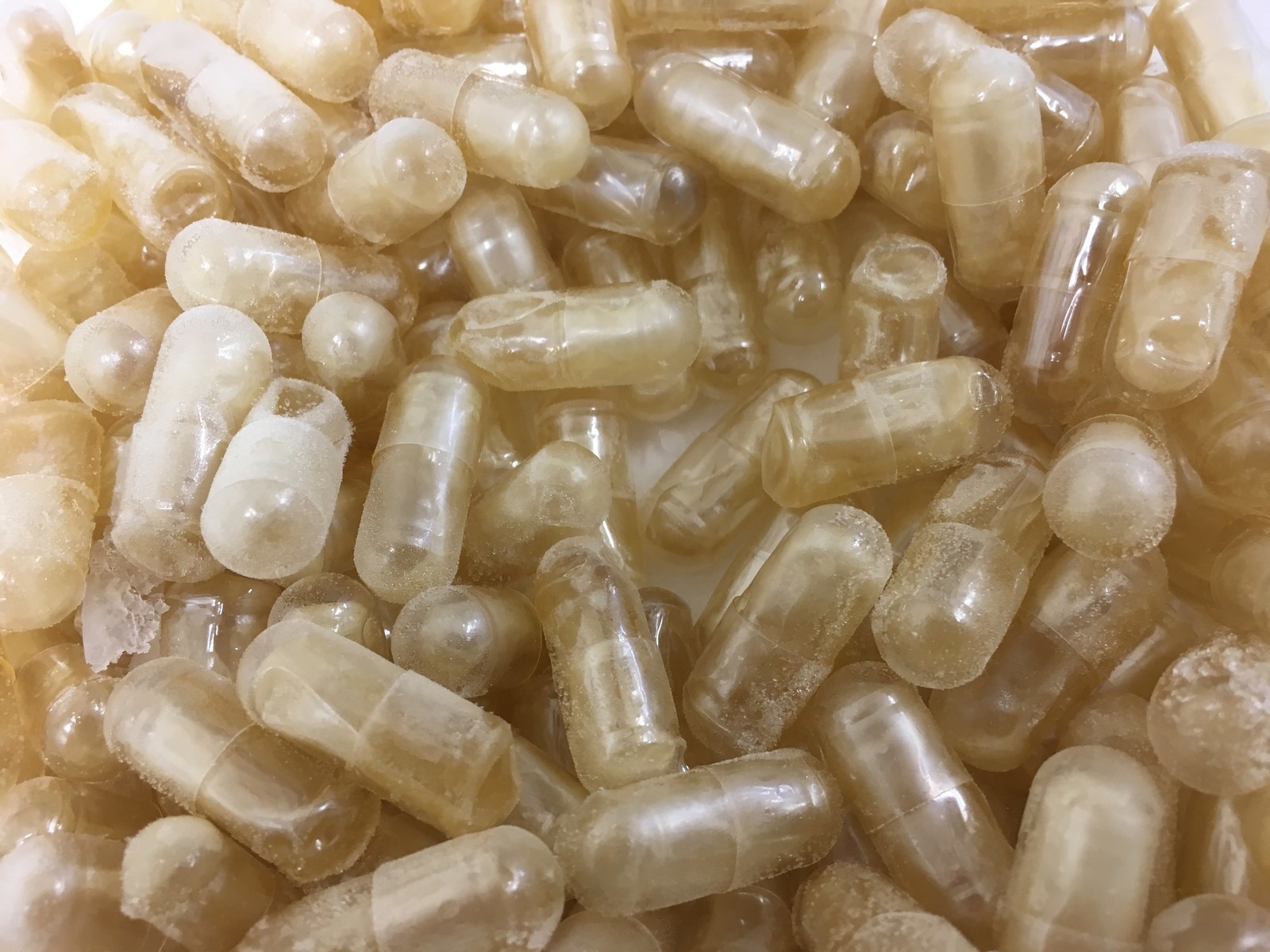

When the Tampa office first started doing fecal transplants, Shepard made the samples himself, adding bottled water to stool and mixing the two in an electric blender. He also made poop capsules, by filling empty pill shells with an eyedropper, for patients who needed a transplant but were too sick to travel.

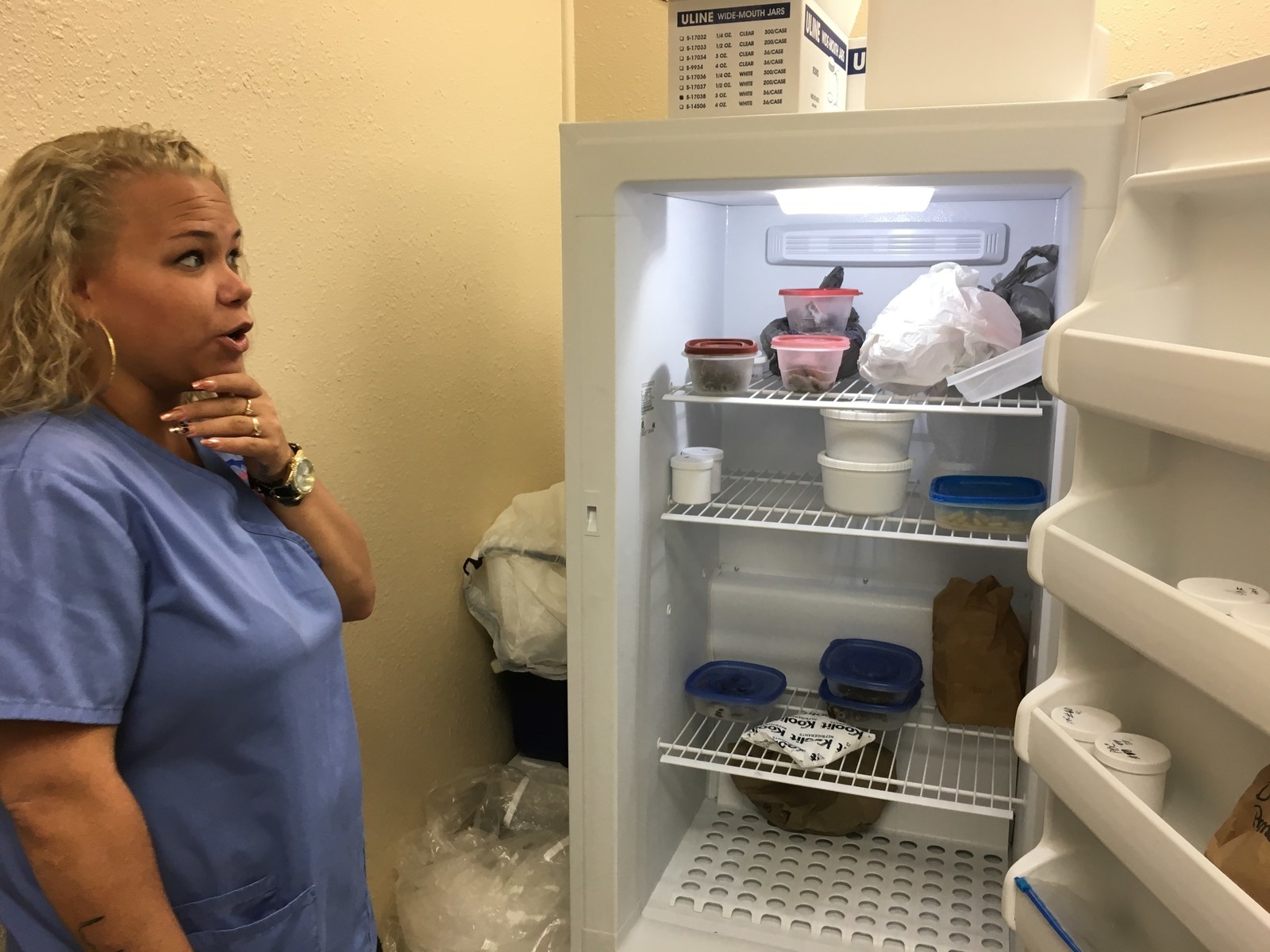

These days, his clinic’s poop is prepped by Helena Lebron, a clinical assistant and steward of the “Transplant Room,” a fluorescent-lit exam room with a sink, freezer, and private bathroom. This is where she shows patients how to perform an “infusion” — a poop transplant delivered through a clear plastic catheter that travels a few inches into the rectum.

Lebron has worked at the clinic for six years, and has been preparing fecal samples for about three. The morning Luke came in for his transplant, she slipped off her finger rings, dropped them into the pocket of her nurse’s smock, and snapped on a pair of lavender disposable gloves.

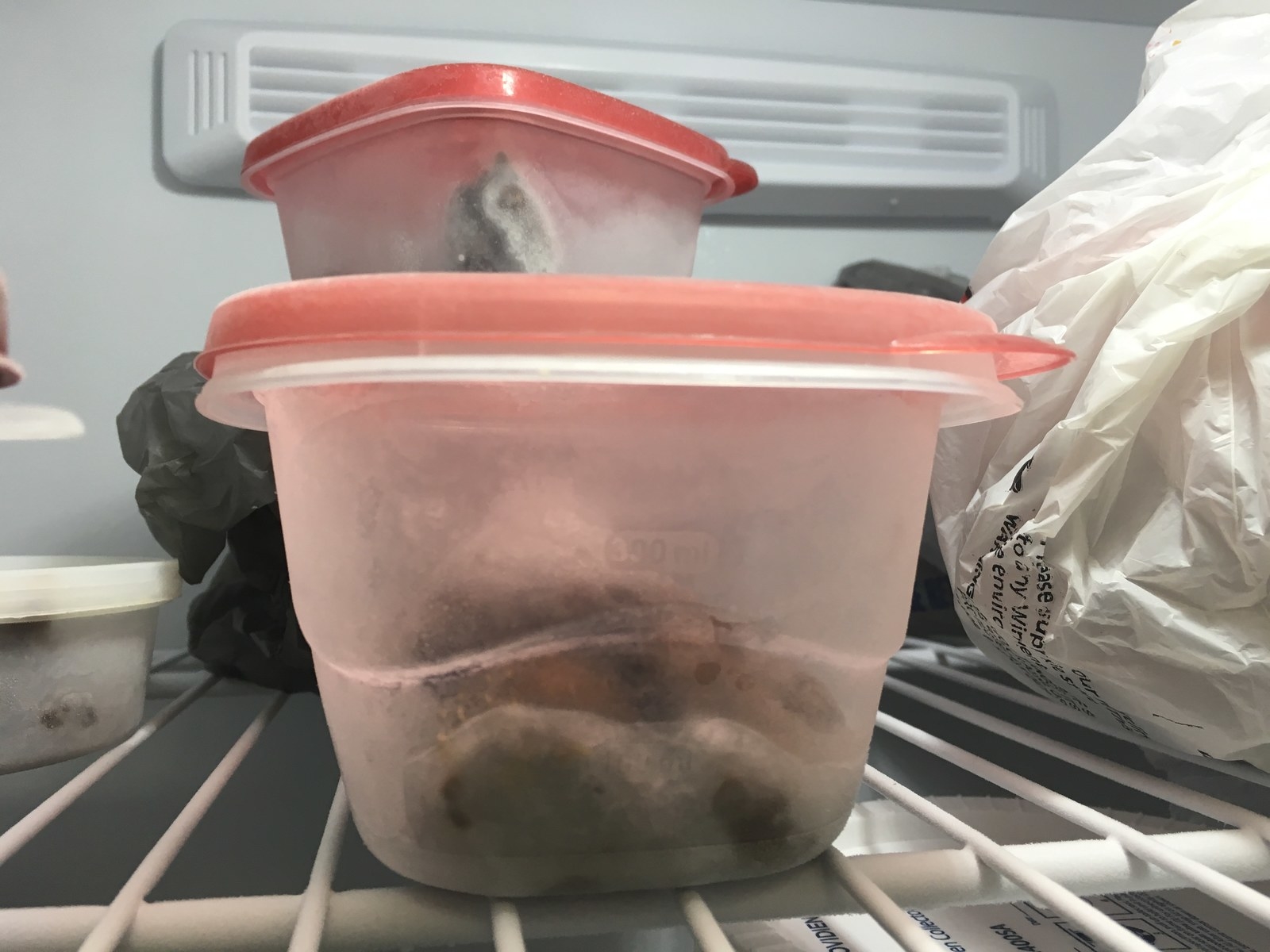

A Tupperware box from the freezer was thawing in the sink. She extracted her tools from a cabinet underneath: a white collecting tub, a bigger vessel to act as a lid and to prevent splashing, a wire strainer, and a handheld mixer with twin metal attachments.

The metal blades hitting the frozen turd sounded like a drill. The smell enveloped the bathroom, then crept into the adjoining exam room. Lebron barely noticed.

The Tampa office gets its stool samples from three donors. One is Michael Garcia, a goateed 27-year-old fitness trainer who will go to graduate school for physical therapy in the fall. He found out about it through his cousin, who works with Shepard.

Garcia does his best to keep his samples pristine, eating mostly complex carbs like brown rice and quinoa, and lean meat like fish and chicken breasts. He’s sworn off junk food and almost never drinks.

“I know it’s helping people so I have that in my head — I have to do this the right way,” he said.

Garcia collects a sample about once a day. He simply squats holding a Tupperware jar in position, then puts on the lid and throws it into a separate freezer he has reserved for poop tubs. He drops off between four and six frozen samples about once a week, and gets $40 for each. Every year, he estimates, he makes at least $7,000 on these donations, money he plans to put toward grad school.

One of the clinic’s other donors is the 14-year-old daughter of two Shepard employees. She wants to be a competitive dancer, so exercise and strict diet are part of her lifestyle anyway.

Lebron has done the procedure often enough that she can tell the donor from the sample. Nodding to the tub in the sink, labeled “MG,” she said, “I know he does a lot of rice and beans.”

He drops off his frozen samples about once a week, and gets $40 for each.

As the mass melted, Lebron held a wire strainer over a collecting box with one hand and swirled the tub containing poop with the other. Then she poured the liquid through, revealing a tattoo in the shape of an EKG pulse running up her forearm. “We really want it to be kind of thick, like a milkshake, or maybe even thicker than that,” she said, adding a little more water into the bowl.

Lebron aims for just over 40 milliliters of filtered product. After about 45 minutes of drilling, swirling, and straining, she closes the lid and the white tub disappears into a cooler, due to be deposited into a patient that afternoon.

Lebron wiped down the basin and platform with napkins soaked in hand sanitizer. Before the equipment disappeared under the sink, she flashes the name of the model: Hamilton Beach.

“Same thing you make your mashed potatoes with,” Lebron said. “Needless to say I make mine by hand.”

Later that afternoon she made another sample. That one was for Luke.

The FDA didn’t weigh in on poop transplants until May 2, 2013, when the agency announced it would consider the procedure an “investigational new drug” — the same label it gives to experimental pharmaceutical medications. That was a big problem for patient advocates like Duff, because it suddenly meant that any C. diff patient getting the procedure at a hospital had to first enroll in a clinical trial.

The announcement was also surprising to the scientific community because of a landmark Dutch study that had just come out. In a randomized control trial of 43 C. diff patients, researchers showed that fecal transplants offered relief 94% of the time. The researchers were so stunned by the results they stopped the trial early, arguing that was unethical to keep the poop treatment from people who could benefit from it.

The FDA made the announcement at a two-day workshop on poop transplants, attended by about 140 doctors, scientists, and other transplant experts, including Duff. When she heard them describe the new regulation, she felt a panic attack coming on. She persuaded the workshop moderator to give her the microphone between speakers.

Duff doesn’t remember exactly what she said, but she tearfully begged the agency to reconsider. In written comments to the FDA later on, doctors and policymakers backed her up: Such a stringent regulation, many wrote, would keep the procedure from saving dying patients.

Two months later, in July 2013, the FDA clarified its position on fecal transplants: The agency would allow doctors to perform the procedure on patients with recurrent C. diff. But anyone else would need to enroll in a formal clinical trial.

Nearly four years have passed, and the science is moving fast. Many studies suggest that chronic GI diseases like Crohn’s disease and irritable bowel syndrome could be helped with fecal transplants (though trials indicate that success might depend on the choice of donor and a longer course of treatment). Stool banks like OpenBiome in Boston have sprung up to furnish researchers with a steady supply of prescreened frozen poop. But the FDA’s stance has only become more restrictive. In 2016, it proposed an effective ban on doctors buying samples from stool banks.

Some scientists and legal experts have suggested that poop be regulated like a tissue — something that was derived from the body, and therefore subject to less stringent regulation than an artificial substance. A handful of startups and pharmaceutical companies are attempting to identify and isolate active bacterial species, and turn them into poop pills, but only two of those attempts are being expanded into large-scale trials. No one has yet been able to distill the combination of ingredients in some people’s poop that has such a seemingly miraculous effect.

It’s unlikely that the FDA will change its position until the messy procedure is replaced with such a pill. Once that happens, some experts expect the FDA will probably shut down poop transplants. That’s Rachel Sachs’s bet, anyway.

In two cases, the procedure reversed “alopecia”: Bald patients grew back some of their hair.

“We don’t actually know because in some ways it’s without precedent,” Sachs, a professor of law at Washington University in St. Louis, told BuzzFeed News.

Some doctors wish the FDA would better enforce the rules already on the books. Take Colleen Kelly, the gastroenterologist at Brown, who was one of the first doctors in the country to offer the procedure. Kelly said she has done about 350 procedures on C. diff patients since 2008. For other infections, she thinks it’s time to hit the pause button on clinical use: No one knows why poop transplants work, which bacteria are key to their success, or what the long-term consequences may be.

“I want this to be legitimate. I want this to be scientifically driven, I want it to be data driven, I want it to be done right,” she said.

She’s seen some weird outcomes herself. In a case report published in 2015, for example, she described how a patient had ballooned from 136 pounds to 170 pounds in the year and a half after a poop transplant. In two other cases, the procedure reversed “alopecia”: Bald patients grew back some of their hair.

In 2016 Kelly and others launched a study in which 4,000 patients with recurrent, antibiotic-resistant C. diff will undergo the procedure and then be watched for 10 years. Until that data is collected, she thinks doing the procedure on other conditions is premature, and that clinics like Shepard’s cross an ethical boundary she holds sacred. It’s why she hasn’t done the procedure on people who don’t have C. diff, though plenty have asked her to.

“I never wanted to be a snake oil salesman,” she said. “To me, doing it for these other indications is like researching on a person without their consent.”

Julie and her husband knew that the FDA hadn’t approved poop transplants, and weighed their options carefully for at least a year. When Luke, at 6, was still nonverbal and beset with a gut infection that antibiotics couldn’t kill, they decided he had more to gain than lose from the $1,100 procedure.

“I know it’s not approved, but I don’t see how healthy bacteria can hurt somebody,” Julie said. “It seemed like a better option to me than medication that causes side effects.”

At Julie and Luke's first visit to the Tampa clinic, the technician Lebron performed the infusion while Julie watched closely. Julie then returned twice later that week and did it herself, while Lebron watched. She wanted to be comfortable with the steps when she recreated the process at home in Orlando, using frozen stool shipped from RDS Infusions.

For about six months, RDS shipped the family samples from its second facility in Atlanta, on dry ice, in batches of eight. (It costs the family $320 for eight samples, plus $100 for shipping.)

Three nights a week, Julie would set out a sample to thaw for about an hour. Then she and her husband would take Luke upstairs to bathe. Afterward, she laid a waterproof mat on the floor of his bedroom and flicked on a white-noise machine. As the room filled with the simulated sound of crashing ocean waves, Julie would repeat the procedure she learned at the Tampa clinic.

“I know it’s not approved, but I don’t see how healthy bacteria can hurt somebody."

Things went smoothly for the first six weeks. Luke was pooping regularly, and though he was uncomfortable during the transplant itself, he seemed to feel better afterward. Sometimes, Julie let him push the plunger on the syringe so he felt like he had control.

But then one day, after eating a popsicle, Luke didn’t poop for 10 days. Julie freaked out. “That’s how it had been when he was 3 years old.”

So in addition to the transplants three times a week, she started giving Luke poop pills — she had bought a batch of Shepard’s formulation from the clinic — on days that he wasn’t getting the bacteria by enema.

At a new school in Orlando, Luke was keeping up. But by the end of March, Julie found it harder and harder to steel herself for the procedure every night. “I’m giving him these enemas like three times a week. It’s not probably a normal thing.”

So in early April, she decided to stop. It seemed Luke, who was growing increasingly fidgety during the procedure, had had enough too.

In some ways the transplants made a big difference: Luke is no longer chronically constipated and seems to be in better spirits as a result. “I would say that he’s going now every other day and I feel like it’s a good improvement,” Julie said. After the school year ended, he even went to a summer day camp.

She stands by her decision to choose what she considered the more natural option over the antibiotics Luke was previously taking. “I want other people to be able to choose what they think might be best,” she said.

But the speech signs Julie was looking for never surfaced. “I wish I’d seen more,” she said in April. But she hasn’t lost hope that things will change. “I feel like there’s a lot more to come from him.” ●