YAYLADAGI, Turkey — The young American arrived in the small Syrian village of Khirbet al-Joz one day last summer, after crossing the mountains from southern Turkey. He made the trek with a group of fellow mujahideen, men from places like Egypt and Tunisia and Saudi Arabia, there to fight alongside the rebels in Syria's civil war. The Arab fighters were battle-hardened, fit and tested from previous jihads. But the American was pasty and overweight, clearly the product of an easier life. "He looked like a child," remembered an opposition activist from the village, who would become a friend. The American spoke only broken Arabic. He kept mostly to himself during his early days in Khirbet al-Joz, as he settled into life in a rebel training camp.

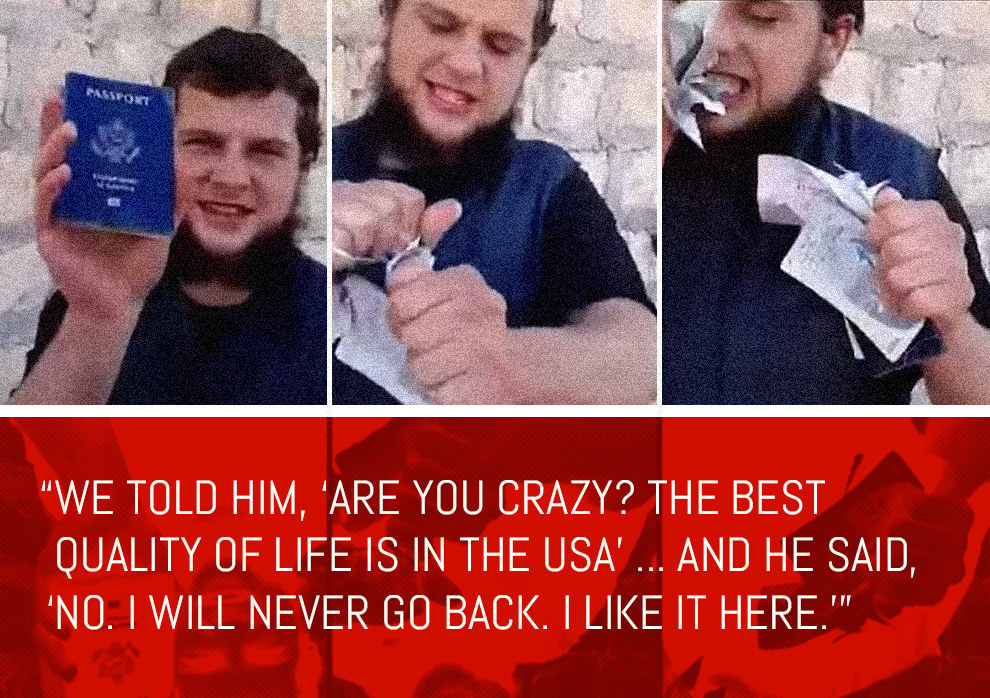

The American was Moner Mohammad Abusalha, the fair-skinned son of a Palestinian father and American mother who grew up in Florida, where his friends called him Mo. By all accounts, his life there had been ordinary: He played basketball and video games and studied the family religion at an Islamic center in a Vero Beach strip mall. But on May 25 of this year, at the age of 22, Abusalha died an extraordinary death inside Syria, driving a truck packed with explosives into a government outpost and detonating the charge. He had been fighting with a rebel group called Jabhat al-Nusra, the Syrian branch of al-Qaeda. In a video he pre-recorded to commemorate the mission, a smiling Abusalha tore at his passport with his teeth, and then lit it on fire.

Abusalha is likely the first American suicide bomber in Syria, though the U.S. government has said that some 100 of its citizens are fighting there. When Jabhat al-Nusra released his so-called martyrdom video last week — in it, Abusalha denounces U.S. policy and calls on his fellow citizens to join the war — it deepened U.S. concerns that Americans are being trained and radicalized in Syria, and that some might return to launch attacks at home.

Yet for much of his time in Syria, Abusalha seems to have flown under the U.S. radar, especially in the early days of his journey. Few details have emerged about how he arrived in the country or got his foothold in the chaotic war. In the video, Abusalha offered only this: "I made my immigration [to Istanbul] with only $20 in my pocket — only enough to buy a visa."

Accounts from the Syrians who hosted Abusalha in Khirbet al-Joz provide the first look at what came next.

"These are the mountains through which he entered Syria," said Mohamed al-Abed, 34, the wiry activist who became Abusalha's friend.

The rock-strewn ridges stand between Khirbet al-Joz and the Turkish village of Guvecci. On a recent afternoon in Guvecci, a boy herded cattle across the sloping road as gusts of wind eased the heat. Abed pointed to a patch of ground beside a convenience store. There, rebels and activists like him, who use Turkey to rest and gather supplies, often pitched a tent as they waited to return to Syria on the smuggling paths nearby. Down the road from the store, Abed revealed one route that Abusalha could have taken: a beaten path in the brush that wound up the mountains and between the guard towers that mark the border line.

Thousands of foreign fighters have traveled to Syria to wage a religious war. The rebels are almost entirely Sunni Muslims, like most Syrians. They want to overthrow a dictatorship rooted in President Bashar al-Assad's Alawite sect of Shiite Islam. Each side is backed by major partisans of the historic Sunni-Shiite divide — countries like Saudi Arabia arm the rebels, while Iran props up the regime. As the uprising that began three years ago as a protest movement spirals ever deeper into a regional sectarian war, and Islamist rebels muscle out the moderates, many Syrians have come to see the foreigners as dangerous extremists.

Abusalha arrived at a time when it was common for them to turn up in Khirbet al-Joz, which rebels took over in the spring of 2012. Local fighters welcomed the mujahideen as brothers-in-arms, happy to have the helping hands. But they'd never seen an American make the trek across the mountains — or someone who seemed so ill-suited for the rebel life. "When we received him, we were shocked," Abed said. "He didn't look like a fighter at all."

Abed's older brother, Bassem, is a commander in a small rebel battalion based in the village. Abusalha wanted to head to the front lines, but Bassem told him that would be a mistake — on top of being out of shape, he didn't know how to fire a gun. He offered Abusalha a spot at his base, where he ran a training camp. "I told my brother, he's just a kid. It's wrong to let him join the battalion," Abed said. "But my brother trained him with the other mujahideen, in the mountains and the forest, around the stones."

The base was an old house set in a wooded valley. The fighters slept three or four to a room, cooked meals together in the kitchen, and sat around talking. There was no running water or electricity and little to eat. Abusalha spent much of his time reading the Qur'an, often asking the other foreigners, some of whom spoke English, to help him understand, or to give him lessons on Islam. He knew only basic phrases in literary Arabic, the language of newspapers and religious sermons — not the Syrian dialect.

Abusalha's training started with treks from one rebel-held village to the next, to build his endurance. Then he began to practice military crawls. He learned to use the Russian-made weapons that are common in Syria, such as PK machine guns and Kalashnikovs. Later, he would learn to build roadside bombs.

"He wasn't ready," Bassem al-Abed said, speaking by phone from Khirbet al-Joz. "But I trained him to be able to fight."

He said he'd trained fighters since the war began — some 2,500, he guessed, foreigners and Syrians alike, though Abusalha was the only American. He didn't know how these fighters had found him, he added — maybe someone had been guiding them his way. But many, like Abusalha, simply seemed to wander into Khirbet al-Joz from Turkey. "There are fighters that come here without any training, and they die quickly and without any effect," he said. "So I train them to help them survive."

He said his battalion, Jund al-Malahem, is close with Jabhat al-Nusra, and that many of the men he trained have ended up there. "They are my friends," he said.

One fighter with the battalion, who goes by the nom de guerre Abu Ahmed al-Lada'ni, recalled his first thought when he met Abusalha: "An American? Come to fight with us?"

Abu Ahmed wondered why a young man from America — who lived in a gated community in Florida, had a high school degree and had attended college, before dropping out — would leave such a life. "We told him, 'The best quality of life is in the USA,'" Abu Ahmed said. "And he said, 'No. I will never go back. I like it here.'"

Abusalha didn't talk much about U.S. policy or politics, his friends said. But he seemed eager to embrace a life far removed from what he knew at home, taking the rebels' simple existence to the extreme. He refused new clothes when summer gave way to a chilly fall. "We gave him clothes to be warm — he didn't want them," Abu Ahmed said. "It was so cold, and he's still wearing shorts. He had holes in his socks, and we tried to give him new ones, and he said, 'No, I am happy like this.'"

Living at the base, Abusalha came out of his shell — smiling to ease the language barrier and greeting locals in his basic Arabic. He jumped out of bed for training sessions and morning prayers — "because he was so motivated for the jihad," Abu Ahmed said.

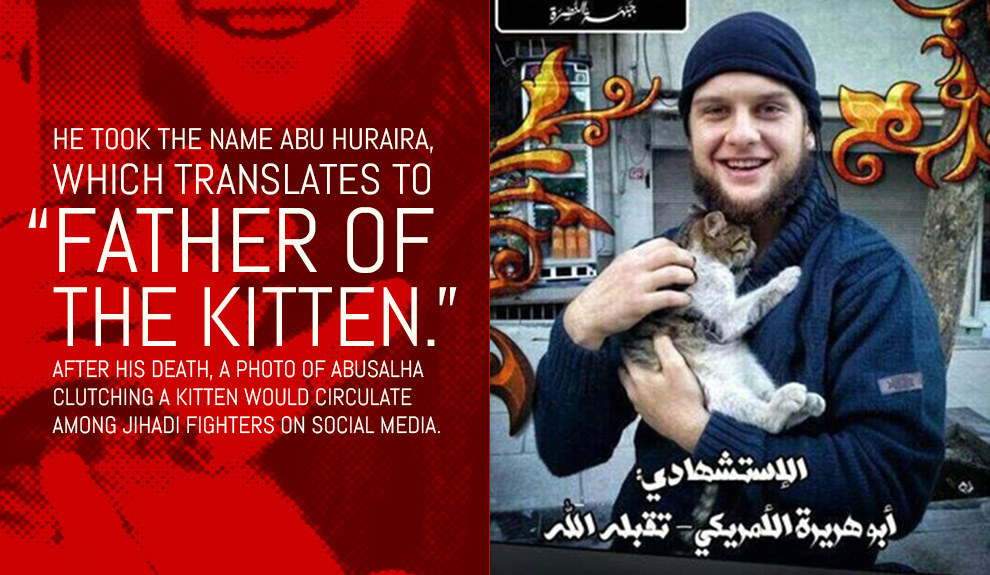

Like many rebels, Abusalha adopted a wartime nickname. This is often dictated by the name of a man's first son, or what he might call the son if he had one — Abu Ahmed means "father of Ahmed." Abusalha took a slightly different tack, in honor of his affection for cats; his friends said he was known to keep a kitten at his bedside. He took the name Abu Huraira, which translates to "father of the kitten." After his death, a photo of Abusalha clutching a kitten would circulate among jihadi fighters on social media.

The name also has deep religious roots. The original Abu Huraira, another lover of cats, was a close companion of the Prophet Muhammad, and his accounts of Muhammad's sayings appear foremost in the teachings of Sunni Islam.

Abusalha came to Syria immersed in a fundamentalist vision of Islam. It wasn't clear where it came from — Bassam al-Abed, the rebel commander, remembered Abusalha saying his parents were unhappy he was in Syria. Once there, though, his religiosity only grew. He began to ask about joining Jabhat al-Nusra, his friends said — their battalion was religious, praying five times a day, but Abusalha wanted something more hard-line. Jabhat al-Nusra is notorious for its al-Qaeda connection as well as its successes on the battlefield — fueled by its soldiers' embrace of death under fire, which they view as the best path to paradise, and their willingness to use themselves as suicide bombs.

It was late fall or early winter when Abusalha left to join Jabhat al-Nusra. Some time after that, he traveled back to Florida, as the New York Times reported last week, though it's unclear why. It's not uncommon for foreign fighters to visit home to rest, then return to Syria. The next his friends from Khirbet al-Joz heard of him was the news of his death.

The story of the American Muhajir:

View this video on YouTube

In the video he recorded before his suicide attack, Abusalha seems to be mimicking jihadi fighters who had made similar videos before him. Sitting on a drab couch with a rifle leaned against his shoulder, he affects an accent, mixes in what Arabic words he can, and theatrically pounds his chest. "The life of a muhajid [religious warrior] is an unbelievable life," he says. "This is the best I've ever lived."

He continues his address for 30 minutes, tugging at his long beard, his voice cracking as he shouts. "We are coming for you," he says, apparently addressing U.S. President Barack Obama. "Listen to my words, you big kufar [infidels]. You think, oh, that you killed Osama bin Laden? You did nothing. You sent him to Jennah [paradise], Al-Hamdulillah [thanks and praise be to God]. You think that you have won — you have never won! You will never defeat Islam."

Abusalha would have had to volunteer to go on his suicide mission. In his video, he rejected the term. "How can you say this is suicide? This is nothing like suicide," he said.

The video is titled "The Story of the American Mujahir." Near the end, it shows the explosive-laden vehicle Abusalha is said to have used in his attack — a garbage truck scrawled with religious phrases and outfitted with makeshift armor. The final shot is of a massive explosion, filmed from afar.

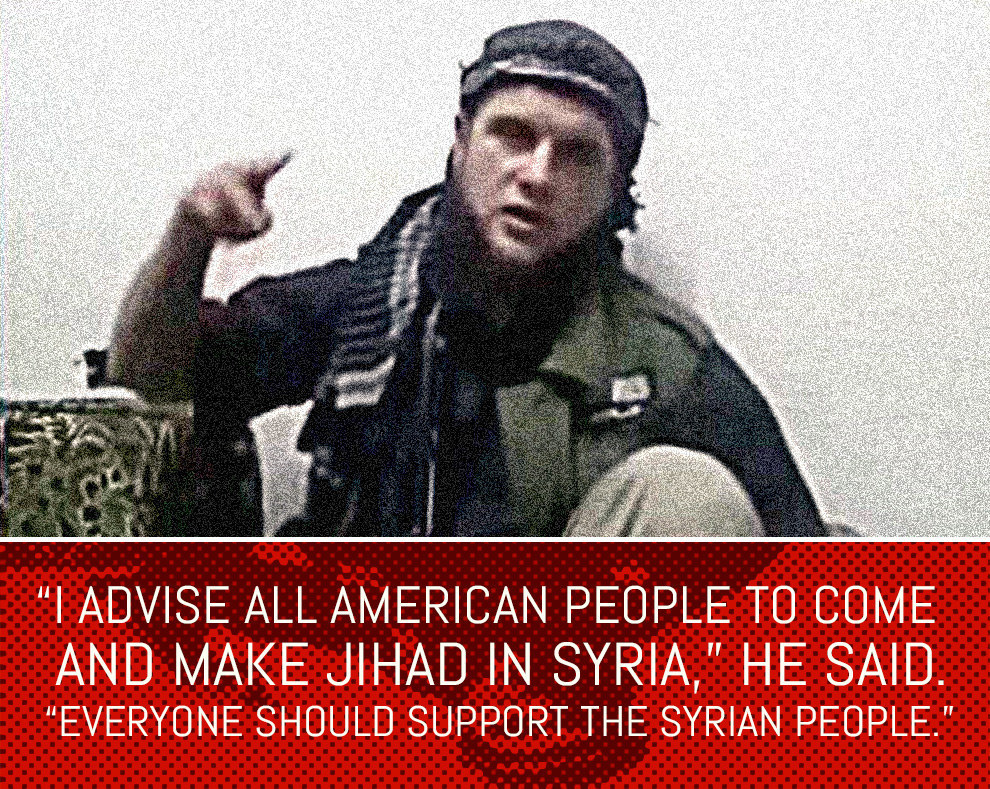

A Jabhat al-Nusra member who goes by the nickname Abu Omar said in a phone interview from Syria that he had encountered Abusalha many times in the province of Idlib, where the attack took place. He claimed that the group was concerned with fighting in Syria, not attacking the U.S., though he recalled hearing Abusalha say that the Sept. 11 attacks had been justified. He knew of more than 10 other Americans fighting with Jabhat al-Nusra in Syria, he added. "I advise all American people to come and make jihad in Syria," he said. "Everyone should support the Syrian people."

After signing up for a suicide mission, Abusalha would have had to wait his turn. When it came, he would have met with a commander to go over the mission, making clear where to drive and where to blow himself up. Ahmed Assi, a Syrian activist and journalist who lives in the Idlib town where Abusalha was based, recounted seeing him just days before the attack, when it was likely in its final planning stages. He was joking and laughing with the other fighters who would join the mission, Assi said. "Anyone who saw how they looked couldn't have imagined that they were planning a suicide mission," he said. "Because they were so relaxed and smiling — like nothing."

Speaking in the Turkish town of Yayladagi, which sits near the border crossing in Guvecci and hosts a camp for Syrian refugees, Abusalha's friends from Khirbet al-Joz, Abu Ahmed and Mohamed al-Abed, tried to make sense of his death. They were uncomfortable with the idea of suicide attacks — "as Syrians, we don't think of suicide missions," Abu Ahmed said — but insisted that Abusalha wasn't an extremist. They described him instead as someone who came to help when much of the world had left them to their fate. "I think he came from the USA to Syria not because he's a Muslim, or because he has a jihadi mind-set — no. Just because he's human," Abu Ahmed said. "And his humanity pushed him to come to Syria and stop the injustice."

The veteran fighter pointed to goosebumps on his arms. "I feel sad because I lost my friend," he said. "But I feel happy because he reached his goal: to die and enter paradise."

With additional reporting by Zaher Said in Antakya.