Roger Williams cannot enjoy fireworks on the Fourth of July anymore. The 68-year-old Texan is a longtime NRA member, but these days, he can’t hunt. Once, during a congressional committee hearing, the chairman banged a gavel — clap — on the desk, and Williams fell out of his seat.

It’s been almost a year since Williams and nearly two dozen of his Republican colleagues were shot at as they were wrapping up baseball practice in Alexandria, Virginia, on June 14, 2017. Williams started the congressional baseball caucus and began coaching the team a few years ago. He’s a standard conservative Republican with a toothy politician’s grin, which he can still flash on command.

He thinks about that morning almost every day. They were practicing for the Congressional Baseball Game, one of those cheerful bipartisan events that's becoming extinct in Washington. It's an annual game, held for charity, where Democrats play Republicans, staffers come out to cheer on their bosses, and everyone shakes hands at the end, reporters and lobbyists looking on.

Waking up predawn to go to baseball practice is a welcome distraction for the Republicans who play — a few hours without the news cycle, or whatever President Trump is doing, or questions about whether they’ll keep control of Congress. Here, Steve Scalise isn't seen as a potential replacement for Paul Ryan; he's the second baseman. Jeff Flake isn't the voice of anti-Trump conservatism; he's a center fielder. Jeff Duncan isn't the Freedom Caucus member and Trump booster from South Carolina; he’s at short.

So Williams thinks about how the team was in shape and feeling good (at least as good as it was going to get). He thinks about how the pitchers weren’t there — he had ordered them to rest their arms — and how they had Republican staffers who’d volunteered to help the team filling in. He thinks about how everyone else was taking their final at-bats and picking up balls, getting ready to head back into Washington. He thinks about what could have gone unfathomably wrong, if everything had not gone exactly right.

At around 7:06 a.m., a man in a blue T-shirt approached the field and fired 62 7.62x39mm rounds through a lawfully purchased Century International Arms SKS-style semiautomatic assault rifle, according to Alexandria’s elected prosecutor. The shooting, he concluded, was “an act of terrorism” that was “fueled by rage against Republican legislators.” The day was one in a continuum of violent, surreal days over the past year, from mass shootings to Charlottesville.

You may love them, or you may disagree with almost everything they stand for, but that morning, the roughly two dozen people on that field just tried to stay alive. Those nine minutes were a near miss of modern American history, between the dark aftermath of a deadly, mass political assassination and our own reality, in which most people don’t think very often about June 14, 2017, the difference between everything changing and almost nothing changing at all.

The day began, however, with a completely different situation, and what it was, was bullshit.

Rep. Chuck Fleischmann had just found out — to his great dissatisfaction — that they were not going to start him in the ballgame.

The year before, Fleischmann, who represents Tennessee’s 3rd District, had started in right field. He was hitting and fielding very well. He has been known to steal a base. He’s short in stature, but fast and cares a lot about the game. “I’m mad. And I’m gonna let everybody know that I’m mad that I’m not starting.”

The Republican team had been practicing for years at this field, a regulation-size diamond with batting cages, in a suburban area. “People go through, they walk their dog, they bring their kids.” The Republicans get out there at 6 a.m., run a baseball practice, then head back into the District, shower, shave, and go to work on Capitol Hill. “It’s the most benign, very quiet, sedate place.” They’d never even had a protester.

Fleischmann would’ve been long gone — practice was basically over — except he wanted to plead his case.

“It doesn’t stop. This guy just keeps cranking out, firing and firing and firing. People are screaming.”

So he walked up behind home plate, OK, to see Larry Hardy, who is and was the pitching coach and played for the San Diego Padres. Larry, look, I’m hot. And Hardy told him it wasn’t his decision to make. I understand that, but I’m pissed off because I come out and I practice hard every day and I know what’s gonna happen — the game will start and I’ll be begging from the first inning on to get in, and they’ll put me in for a half inning at the end and I won’t get an at-bat. And Hardy’s telling him, no, no, it won’t be that way—

“We hear from over in this area just a loud, single bang. Just one.”

The sound startled Will Batson, a Senate staffer and former NFL punter who was throwing batting practice, enough that he almost hit Rep. Rodney Davis.

There was a pause. Only a few seconds, but long enough to experience what Rep. Steve Pearce would describe as a “strange, dissociated notion that I can’t imagine that loud of a metallic sound.” A filing cabinet falling off a moving truck, a firecracker, some nearby construction, a car backfiring, maybe?

“It doesn’t stop,” Fleischmann says. “This guy just keeps cranking out, firing and firing and firing. People are screaming.”

“People, staff, and players,” says Rep. Joe Barton, “were just like quail, were scattering.”

When the shooting started, Matt Mika started running toward the Capitol Police, who were parked about 20 feet from the first-base entrance. He ran for the open gate, just behind the first-base dugout, trying to get out, trying to get to the police, hoping to be helpful.

Mika is a handsome guy, and young, at least compared to the team’s players. He’s a lobbyist who volunteers with the team, the kind of well-liked guy who knows everyone in Washington.

“Three or four of us were kind of huddling right there trying to get out the gate at the same time,” Batson says. “I saw Matt, saw him kind of hesitate a little bit.”

"Matt’s like, ‘Dude, I’ve been shot.’"

This is where Mika got hit. The bullet punctured his right lung, which collapsed, and went out his chest. He had three broken ribs, a cracked rib, a floating rib. The bullet hit his sternum. Missed his heart by less than half an inch. “7.62 is the bullet, that’s like an inch and a half — so that went through my chest.”

But Mika continued to run.

“We got outside the gate...turned around,” says Ryan Thompson, another staffer, “and Matt’s like, ‘Dude, I’ve been shot.’”

They told him to get down, to lie down behind the Capitol Police’s SUV. So he did. He lay down on the pavement. Special Agent Crystal Griner tried to protect him. She was engaging the shooter. She got shot in the ankle. He got shot again, too, in the arm.

It was hot inside his chest. His Detroit Tigers jersey was open, with blood all the way down. “I have a hole in my chest. Everyone can see my heart.”

Mika never felt either bullet. He stayed on the ground, just trying to breathe. “Time slowed down.”

Steve Scalise knew he was shot instantly. He felt something as he was trying to turn away from the shooter. “My legs gave out, and I fell down.”

He knew he had to keep moving or risk another bullet. “You didn’t know how long it was going to last, or what was going to happen next, or, you know, if you were going to get hit again.”

And so one of the most important politicians in America started crawling, using his arms to pull himself toward the outfield from second base. He started praying. He started moving less and less.

After he’d reached shallow grass in right field, his arms gave out.

It felt like forever. People who had made it off the field were calling out to him.

But he stayed out there, alone, because no one could reach him.

Zack Barth could see the shooter from center field. “Not everybody could.”

He saw him — right next to the third-base dugout — and he saw him keep shooting. Pop, pop, pop, pop, pop. Barth started to run. He wanted to put as much distance between himself and the shooter, to get as far away as he could. He ran into right field, right behind one of his friends. The outfield fence is tall, something like 20 feet, but there’s a big gate, so Barth — a quiet 25-year-old staffer for Williams — went for it.

The gate was locked. He’d run into a corner. “There’s nowhere I could go.” The gate was locked and Barth was trapped inside the field.

The gate was locked. He’d run into a corner. “There’s nowhere I could go."

“So I just kind of hit the deck.” He and his friend dropped to the ground, lying on the warning track with nothing between them and an SKS-style semiautomatic. He saw the shooter turn their way. “Then you start hearing, like, things popping around you.” Gravel was going everywhere.

There wasn’t pain, or at least not pain he was thinking about. But his leg was hot. Really hot. “I could feel how hot it was and I definitely knew, like, I had gotten shot.”

His friend climbed up the fence, way up in the air, then jumped down. Barth tried to follow him up, but quickly realized he wouldn’t be able to do that. A bullet had gone straight through his leg.

So he did the only thing he could: run. He turned and ran toward the first-base dugout, maybe 60 feet, from outfield to infield, past Scalise, whom he could not help, back closer toward the shooter.

“I jumped into the dugout. Roger happened to be right there. And so I just kind of — I mean, the way he describes it — jumped into his arms.”

“He dove into my arms; it’s like God brought us together,” Williams says.

When the shooting started, Williams knew he needed to get inside the first-base dugout. Unusually, the field’s dugouts are real — you step down into them, like on a pro baseball field. “Real dugouts. And I remember, so my brain said, I gotta get to that dugout. So I dove into that dugout and I literally was like diving into a swimming pool with no water.”

This is where a bunch of them hid, everybody from Sen. Jeff Flake, the Trump critic, to Rep. Mo Brooks, the Freedom Caucus member from Alabama, feet below the field.

“All we could hear was this guy firing this ... weapon,” Williams says.

Surrounded by cinderblock and lying on concrete, every noise was in stereo. “It just kind of echoes around in there,” says Flake. “That was pretty horrifying to hear all that.”

And ricochet bullets were landing there, too. It occurred to a few of them then that maybe the dugout wasn’t really that safe after all. And if you go to the field, you can see bullet holes through the top of the dugout, sheds, and metal poles on the fence.

If you go to the field, you can see bullet holes through the top of the dugout, sheds, and metal poles on the fence.

“It would be pretty easy for him to just start shooting in there and hitting people — ’cause you couldn’t miss, we were so tightly packed together,” Brooks says.

They kept waiting for the Capitol Police to fire back. (At least one person worried that maybe the agents had been killed, and then...?) They kept waiting for it to end, hoping that they could get out to Scalise, who some could see trying to drag himself into the outfield. They just kept waiting, for what felt like forever, for any noise that wasn’t the shooter. “If we could hear sirens, we would know somebody’s coming to help us,” Williams says.

And then came the shots from the Capitol Police.

The difference in the shots was audible: boom boom boom versus ping ping ping. “As opposed to that rapid fire of a strong semiautomatic-weapon ba-bam ba-bam ba-bam that just kept coming and kept going,” Fleischmann says, “we heard pow pow pow pow.”

Still, even as all this was going on, “everybody was doing something,” Williams says. “I had somebody tell me, ‘Well, I bet you were freaking out.’ Nobody freaked out.”

Flake and Brooks used Brooks’s belt to make a tourniquet for Barth’s leg. “It was funny, you know, he’s putting a tourniquet on my leg,” Barth says, “and I never really talked to Sen. Flake before; he was like, ‘Oh yeah, and hey, I’m Jeff.’ I was like, ‘Well, I’m Zack.’”

The men also hustled Rep. Joe Barton’s 10-year-old son, Jack, into the dugout and shoved him under the dugout bench. Two people lay down in front of him.

“That’s when I got my phone out,” Barton says. “And I called 911, and the first time it was busy. I tried to call it again, and I got somebody in Colorado. So I dialed some crazy number, I got somebody in Colorado, so I hung up and I called 911 again.” This time, he dialed right, got through, and tried to explain the situation.

“I hung up, and you couldn’t hear any more shooting, and so people (were) kind of poking their head out, and that’s when I got up.”

“Once I saw the shooter drop, and I knew they had him,” says Rep. Brad Wenstrup, “I took off.”

A man in the nearby dog park filmed a short video posted to YouTube: minutes of the shooting, and a slumped figure, Scalise, in the outfield. As the last blast of bullets ends, several figures race toward him.

Wenstrup, a doctor and Iraq war veteran who had been a medic on battlefields, reached Scalise and did what he’d done so many times before: assess his patient — and Scalise was still conscious. This was good. Steve, can you move your right leg? He could. Also good. Just your foot, just move your foot. Your left foot. A quiver — nerve damage. Wenstrup tried to keep him awake. Steve, can you count to five? Someone took off their shirt so it could be used to apply pressure on the wound. Wenstrup pulled down Scalise’s pant leg — he could see where the bullet had entered. Then he looked on the other side for an exit wound. There wasn’t one.

This is when Wenstrup knew things were bad.

“If there’s no exit wound, that means it went up. And if it went up, now you’re talking a blood vessel.” Blood vessel bleed, internal organ bleed, bone bleed...

Wenstrup remembered a case in Iraq: a soldier who’d suffered a blunt injury to the hip. The soldier saw medics; things were in process. Then he started to drift, the wound started to weep. By the time they opened him up, they were too late. The soldier bled out internally.

Did anybody have a belt? Wenstrup needed one. A belt appeared. Then other things started showing up. Bandages, scissors, modern tourniquets. Wenstrup cut Scalise’s pants open. He put the tourniquet — a CAT tourniquet, as in Combat Application Tourniquet — as high as he could. “You want to stop the bleeding, at least to the leg. I can’t stop what’s going on inside, but at least to the leg and the femoral artery.” He was concerned about the iliac arteries, which run through the pelvis to the hips. So he put the tourniquet on as high as he could, as tight as he could, and taped it on.

Medics started showing up. Did they have a clotting bandage? They handed him a kit — right on top. Gauze, then the clotting bandage, went over the wound.

How quickly could they start an IV? If Scalise were losing fluid… “You’d rather have blood, but you don’t want your vessels to collapse and your heart to stop.” They couldn’t start an IV. The gates were still locked and the medics couldn’t get their ambulance on the field. Wenstrup didn’t want to move Scalise. “Because if the bleeding is starting to stop inside, or whatever, you know, you don’t move him much.”

But they had to keep some fluid going through him; if he was losing fluid, they had to keep some fluid in his system. Steve, can you drink? Wenstrup said. I’m thirsty, came the reply.

Get that Gatorade, just do what you can. Go get some water, whatever you can. Steve, drink as much as you can.

The first thing Richard Krimmer, a first responder, came across when he got to the outfield was a gentleman saying he was a doctor, and that he’d put a tourniquet on the victim.

The tourniquet was applied high on the thigh and was working wonderfully. There was no bleeding. The patient was awake and talking, so Krimmer asked him his name. All right, Steve, we’re gonna take care of you. “Ended up being obviously Congressman Scalise — I didn’t know that for quite a while. We were simply treating him as just a normal patient.”

"I could sense that I was starting to fade. And I could feel my body shutting down. And, you know, I wasn't sure if I was going to make it."

There were no other injuries that he could see. So they lifted him by the uniform, onto a stretcher, and into Krimmer’s ambulance. He started an IV, a couple of advanced procedures, trying to figure out how bad things were. Scalise, very pale, said he wanted to call his wife; everyone in the medic unit grabbed their phones. The supervisor from Arlington was the fastest on the draw. Scalise left his wife a message, something "that I wanted her to hear in case I didn't make it."

"I could sense that I was starting to fade. And I could feel my body shutting down. And, you know, I wasn't sure if I was going to make it."

The ambulance actually started moving. But a helicopter landed on the baseball field, so they quickly transferred him over onto that instead, and up it went, leaving Brad Wenstrup and the rest on a shell-covered field.

"I'm praying my friend makes it," Wenstrup says. “In there ... that's what you've got to do. Do what you can do. Do anything you can possibly do. And now, after that, it’s out of your hands and it’s like, ‘Oh dear God, please let him live.’”

Matt Mika was pale, really actually gray, when the paramedics arrived. “It’s a look of impending doom,” says Chad Shade, one of the paramedics who treated him. “When you have done this job for enough time, when somebody looks the way that Matt looked... I would have never thought that Matt would have survived.” Capitol Police Special Agent Crystal Griner and Rep. Barry Loudermilk said the Lord’s Prayer over him. He doesn’t remember that happening, but everyone tells him it did.

Mika thinks they had him wrapped up and on the ambulance by 7:30 a.m., then right onto Route 1 and to the George Washington University Hospital emergency room by 7:45.

“I was praying. Two, trying to keep myself awake.” Chad Shade kept asking him questions. Mika asked him to call his dad; he remembered the phone number, which Shade dialed. Mika had just started dating his girlfriend a few months earlier and didn’t know her number yet by memory. He kept thinking about movies, and how people die in movies, and he didn’t think that he looked like that, even if the paramedics could see his heart. “I knew blood wasn’t coming out of my mouth, I knew my chest was open, I knew it was really hot. I knew I could breathe, they were helping me. … I was also talking to my mom who passed away 10 years ago from breast cancer. I knew I was OK; when I got to the hospital I was like, ‘All right, they’re gonna put me under.’ And then I don’t remember much from Wednesday to Sunday.”

If you ask the people who survived, a series of miracles took place that morning, which Roger Williams considers “angels,” and Rep. Jeff Duncan, “God winks.”

That the shooter never got a good shot into the dugout. That his first shot hit the fence, diverting the bullet’s path away from Rep. Trent Kelly who was standing directly in front of him, at third base. That he never thought to climb the announcer’s booth. That the pitchers weren’t there that day, instead of trapped in a batting cage. That Matt Mika was turning his body when the first bullet struck him, so it didn’t hit his heart. That Zack Barth could still run. That Dr. Brad Wenstrup didn’t leave early. That Richard Krimmer’s ambulance hit green lights the entire way to the field. That the gate next to third base — through which the shooter could’ve walked through right onto the field — was locked, another fact nearly everyone on the team credits with saving their lives.

"If it was just one thing, you could maybe call it a coincidence, but when you add them all up together, the only way you can explain it is that they were all miracles,” Scalise says.

“The irony is because Steve Scalise was there, we all survived.”

That Steve Scalise was even at the field was a miracle, too.

“The irony is because Steve Scalise was there,” Rodney Davis says, “we all survived.”

Because he is the third-ranking Republican in the House of Representatives, Scalise has a security detail — on that morning, US Capitol Police special agents Crystal Griner and David Bailey. It’s against department policy for agents to speak with the press, so they haven't been able to tell their story. But all the Republicans who were at the field that day, and the prosecutor’s report, can tell you everything that Bailey and Griner did, will tell you they are heroes, will tell you to talk to them about what they did. They put themselves directly in harm’s way, engaging the shooter so he started firing back at them, instead of at everyone else.

Bailey ran onto the field. Per the prosecutor’s report, he heard bullets go by his head and then kept firing back from near the first-base dugout. When Griner got shot through the ankle, she kept trying to engage the shooter from the ground. She propped herself up against a tire and attempted to triage Mika, talk to him, keep him awake until help came. Bailey kept engaging the shooter, having moved back toward the SUV, and continued firing at him as the Alexandria police arrived. He got hit at some point, too, on the inside of the right ankle, by a large piece of shrapnel.

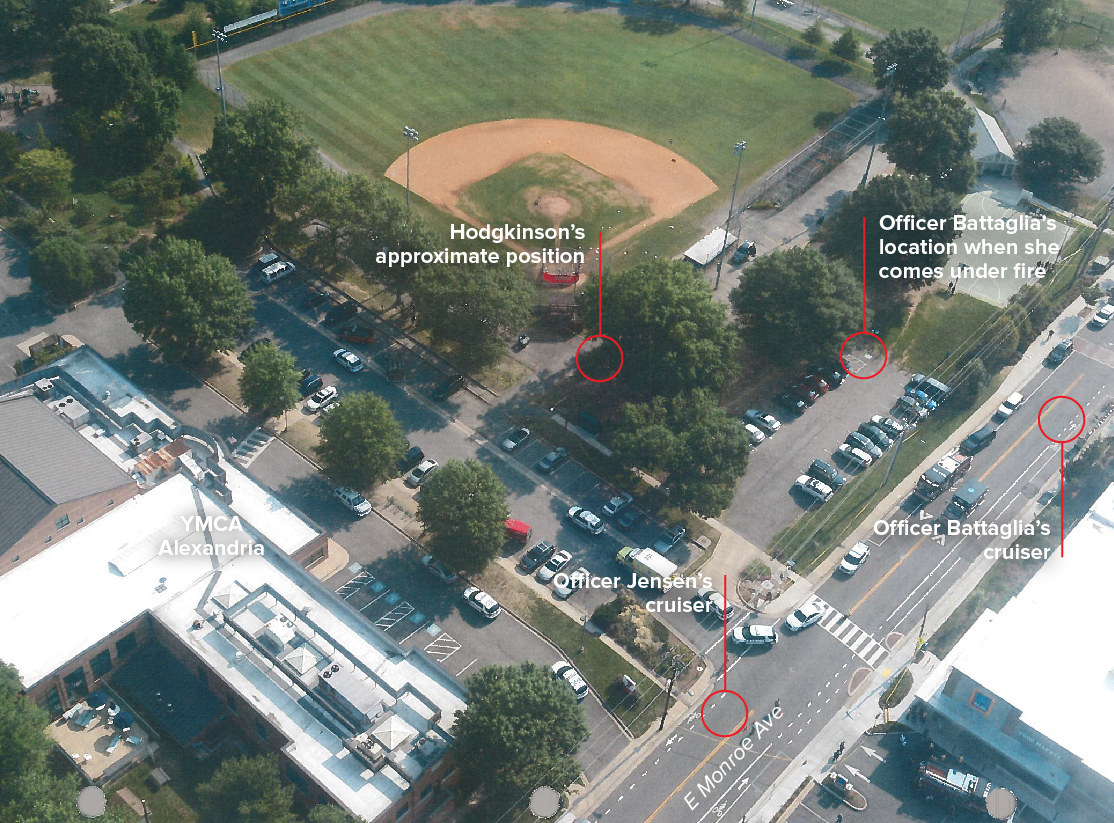

According to the prosecutor’s report, at least six 911 calls were made between 7:09 and 7:12 a.m. Alexandria police officers Kevin Jobe, Alexander Jensen, and Nicole Battaglia arrived there in separate cruisers, and ultimately surrounded the shooter.

"She was fearless, in my opinion. I mean, I broke down when I met her because it was just, like, I’ll never forget that visual of her — just, 'I’m here to save the day.'"

Battaglia, who was closer, drew her weapon and ran toward the shed where the shooter was still firing at the Capitol Police. “I remember watching this very petite policewoman; she came charging in gangbusters. And people are yelling, ‘Stay down, take cover,’” says Wenstrup. “She knew what she was doing and she was fearless, in my opinion. I mean, I broke down when I met her because it was just, like, I’ll never forget that visual of her — just, ‘I’m here to save the day.'”

She got pinned down. Jensen, stationed farther back behind them, hit the shooter in the right hip with a Bushmaster rifle. The shooter fell, dropping his rifle, but then got back up and began firing with a handgun. Jobe and Bailey kept firing at the shooter, and Bailey was able to hit the shooter in the chest. Jensen fired another shot, hitting the shooter in the left hip this time. He was down. By 7:15 a.m., just three minutes after the police arrived on the scene, they had the shooter in handcuffs.

Later, Bailey would tell others that he realized his phone had maybe saved his life — it took a bullet instead of his hip, and he happened to be holding it in the exact right place at the exact right time. Williams, as he relays this story, shows a photo of Bailey’s phone on his phone to remind him of this particular miracle.

“If Steve’s not there, he doesn’t get hit,” Wenstrup says. “But if Steve’s not there, there’s no one firing back. And you could have seen about 20 people laying on the field.”

There are other miracles, too, the kind that you have to see to believe. Mika is playing sports, even though he had a hole through his chest and shrapnel is still in there.

“I’ve been going to the batting cage, I’ve been throwing, I’ve been biking, playing hockey,” he says.

His doctor at George Washington University Hospital, Libby Schroeder, says that if the bullet had gone a few millimeters in any other direction, Mika would have died on the scene. But he was as stable as he could be by the time he arrived at the hospital. “At that point, my job became closing holes, essentially,” she says. One reason: the military-grade chest seal that paramedics applied to his wound on the scene — it’s equipment and training Alexandria Fire Chief Robert Dubé says they wouldn’t have had years ago, but now departments train specifically for large-scale shootings and have the equipment to deal with it. Mika’s body began to heal so quickly that they nicknamed him Wolverine. As he recovered, especially in the early days, friends and family would come visit him. “Sometimes they just wanted to see me, you know, just touch me. I mean, I was supposed to be dead that day.” His ribs are still injured — not much he can do about that; ribs take a long time to heal — but he’s getting there.

He’s compared scars with Steve Scalise, who can walk with the support of braces, despite his ongoing treatment.

Mika believes he is alive for a reason, “that the man above has got a better idea for me and for all of us, and so we’re all trying to figure out what that is.” He talks all the time with Bailey, Griner, his paramedics, his doctor, his physical therapists, the lawmakers who were there. They are a community now. “All these miracles and things have brought us together. And we— I would have been friends with them if I had known them. This thing kind of brought us together.” He’s connected with other victims, too, from other shootings, with wounds similar to his.

“I’m just trying to get back to that new normal and just be me.”

Some of the players don’t want to talk about the man who opened fire on them, or even think he should be discussed. None say the shooting changed what they thought about gun control, except that if Washington had different gun laws and they could carry weapons, maybe some of them would have had guns in their cars.

But many lawmakers are mad, or frustrated, or saddened, at how quickly the story disappeared from the headlines given that the shooter, James T. Hodgkinson, targeted Republicans. The FBI concluded the shooting wasn’t politically motivated — suicide by cop, they told members after an investigation.

Hodgkinson carried a list of names of lawmakers in his pocket: Mo Brooks, Jim Jordan, Trent Franks, Scott DesJarlais, Jeff Duncan, and Morgan Griffith.

But Hodgkinson carried a list of names of lawmakers in his pocket: Mo Brooks, Jim Jordan, Trent Franks, Scott DesJarlais, Jeff Duncan, and Morgan Griffith. The list included their office numbers and short physical descriptions. He’d recorded video of the field in April of that year — a sign, the prosecutor wrote in his official report, that Hodgkinson “had already selected Simpson field as a potential target as early as April 2017.” Rep. Gary Palmer says he had noticed Hodgkinson on the bleachers the day before the shooting; he’d even thought about walking over to him because he looked like he was having “a hard time.”

According to the prosecutor’s report, Hodgkinson had fallen on hard times. He had stopped working and traveled from Illinois to DC sometime in March 2017, telling his family he was leaving to “protest.” He was living in his van near the YMCA, a building adjacent to the field, that he used to shower. His social media posts show that he hated Trump, and supported Bernie Sanders, whose 2016 campaign he even volunteered for. (“I am sickened by this despicable act,” Sanders said the day of the shooting.) He once routinely wrote letters to the local paper, criticizing Republicans.

Duncan left practice early that morning to see Brigitte Gabriel, the prominent anti-Muslim activist, who was speaking at a breakfast and whom Duncan calls a friend. But he realized later he had spoken to the shooter, when Rep. Trent Kelly explained to him what happened that morning. “And a guy approaches me or is standing there, and he says, ‘Hey, can you tell me who’s practicing this morning, Republicans or Democrats?’ And I said, ‘This is the Republican team.’ He said, ‘OK, thanks.’”

The Alexandria prosecutor called the shooting terrorism, a distinction that Brad Wenstrup thinks applies to school shootings like Parkland and Sandy Hook, too. (“Those are acts of terrorism. I don’t know how else to describe it.”) A spokesperson for the FBI’s Washington Field Office said that Hodgkinson “espoused anti-Republican rhetoric,” but that because Hodgkinson is dead, “We may never know his motivations.”

The FBI briefed the players on their findings in the fall of last year. Several members were shocked they wouldn’t call the shooting politically motivated. Palmer ended up leaving after about a half hour.

“I think most people were really upset,” Palmer says. “I think I may have been the first one that really called them out, and then after I did everybody kind of piled on. I guess everybody was upset. Everybody knew that what they were saying was a crock. The guy had a list. He came there to shoot Republicans.”

He thinks they “misrepresented what happened because of concerns over the political fallout."

“I felt like they blew it off," he said.

“They said, ‘So, essentially this was suicide by cop.’ And we’re like, ‘Only?’ And I can tell you, I can buy that from what I saw at the end, where he walked out openly shooting,” Wenstrup says. “But let’s not kid ourselves here. You look at his website. He hates Republicans. He had the names of six Republicans in his pocket. He had — his social media is full of it. He camped out there for two months planning this, to kill Republicans. Did he hope to die at the end? Maybe.”

First responders worked hard to keep Hodgkinson alive, even as he was handcuffed on the ground. He died later at the hospital.

Once he was down, Joe Barton went to look at him. He took photos until the police yelled at him to stop. “I told the police to shoot the son of a bitch, which they didn’t do anymore.”

The day lingers in all kinds of different ways for the people who weren’t shot, the ones who left early, the ones who should’ve been at practice but weren’t.

One thing that endures is the mix of anxiety, prayer, and dreamlike normalcy in the hours after the shooting. Cops shepherded the Republicans away from the field, onto a basketball court for questioning, then, finally, into a bus back to Washington.

Few had their phones — people’s belongings were locked away in cars and on the field, awaiting police clearance, holding everything from Rodney Davis’s wedding band to their gloves, which they needed for the next day’s game — so lawmakers and staff tried to remember phone numbers from memory. Their own offices were unavailable so early in the morning. “There’s eerily a kind of sense of normalcy when you’re on that bus,” says Davis, “but we’re all just kind of sitting around, staffers, members, anybody who was there.” People didn’t talk much on the way back; they even sat in normal Washington metropolitan area traffic.

“We had people in shock. I was probably in shock,” Fleischmann says. “They bring us back to the Capitol and then just drop us off.”

They spoke to reporters in the hallways. They went to meetings. Leadership in both parties gave speeches about unity. Democrats checked in on Republicans — the kind of communion lawmakers say you don’t see if you’re not in Washington. Roger Williams, on crutches, gave a press conference. (He doesn’t remember much of it.) Fleischmann later went to dinner at the Capitol Hill Club, where he ate for the first time that day. While he was sitting at the table, his body entirely cramped up, and he started to scream. After about five minutes, his body loosened up and he was fine.

“We had people in shock. I was probably in shock. They bring us back to the Capitol and then just drop us off.”

“Folks that didn’t get shot at one of these have a harder time,” Mika says, “because they do the what-if game.” He has friends who were fine — until they saw him in the hospital. “The feeling of, How did Matt get hit when I was right next to him?”

“Steve was shot and I wasn’t,” says Jeff Flake. “I don’t know how to figure things out.”

Fleischmann’s wondered before: “Why didn’t he shoot me?” So, too, has Jeff Duncan, who spoke to the shooter and whose name was on that list. “Maybe he just didn’t recognize me because my appearance that day, maybe he just wasn’t ready. I don’t know.”

“I was not there to help my teammates,” says Rep. Bill Johnson, who left practice early that morning. “I’m not afraid. I would never want to be in a situation like that. I certainly wouldn’t choose to be in a situation like that. But I feel very guilty that Steve Scalise and Matt and the other young man that was wounded, that that happened to them and I was not there to help.” But then again, Johnson’s teenage son normally comes to the last practice — except he was at basketball camp, and what if he’d been there? Johnson is grateful, too.

Richard Krimmer, one of the paramedics who treated Scalise, is still angry that the Republican was seen on camera as he was put on the helicopter. “I didn’t protect him well enough.”

And then there’s the question of how to proceed, what to do with memories of the day. Some of the lawmakers have struggled with loud noises, or have a trick for handling them (set off fireworks ahead of the big ones so you can become accustomed to the sound). There’s a wide range of how people dealt with the day. Rep. Steve Pearce, a combat veteran, saw a parallel to the aftermath of that experience. “I didn’t mind the memories and I didn’t reject the things that happened,” he says of Vietnam. “But some people wanted to internalize it and stay there and at my age, they’re still there. And so that I didn’t want. And I don’t want it for this, either.”

Zack Barth, who was in and out of the hospital the same day of the shooting, had trouble sleeping the first night. But he happens to be OK — in part, he thinks, because he’d already had a near-death experience in his life (emergency brain surgery at age 9). He dealt with this one by turning to his faith, and turning to his friends, his friends from church, his Bible study group. “Knowing that, like, there’s gotta be something better for me out there, you know; there’s gotta be some grander plan.”

“You ask my friends and they would say, like, ‘Oh, he’s just the same guy,’” Barth says. “What would it change about me? I’m not special or anything like that; I just, you know, can’t dodge bullets.”

There’s been a lot of discussion the past year about where this broader moment fits in American history, which past era it might resemble. Are we living in 1968, on the precipice of more violence, assassinations, disruption, unrest? Is it more like the 1970s? Or a different period, something new altogether?

What is certain is the disquieting way June 14 slipped beneath the news so quickly. The shooting felt much further away by July, August, September than mere months. If people joke about how the weeks feel like years in the current era, there’s an unsettling truth behind the joke — the way anything can lose scale and proportion. Two dozen members of Congress were nearly killed one morning last year, and the country didn’t change very much at all.

Many lawmakers talk about the need for greater security, their leeriness about divulging too many details about public appearances, the fleeting worry when someone asks them if they are members of Congress, the precautions that started years ago, when former Democratic Rep. Gabby Giffords was shot at a routine event in Arizona. With this talk of security, there is an implicit acceptance of some darker reality. Whatever it is that’s wrong, it might just be too complicated to fix.

Two dozen members of Congress were nearly killed one morning last year, and the country didn’t change very much at all.

At the end of April, the GOP baseball team practiced together for the first time, both for the season and since the shooting. The game will take place this year on the anniversary of the shooting, June 14, 2018. It’s the last game for a lot of players. Flake and Barton aren’t running for reelection. Neither are Tom Rooney, Ryan Costello, or Dennis Ross. Ron DeSantis and Steve Pearce are running for governor in their home states. Steve Scalise isn’t going anywhere, but was still recovering from his latest surgery. It wasn’t the same kind of practice as before, when no one ever thought twice about it: Reporters and cameras were waiting outside the field. A lot of security was, too.

Many had been back to the field before that day, with family or with other lawmakers. Williams had resisted going. He talks about the shooting as life-changing. “I don’t want to say it means more, but I feel it more,” he says.

He’d always been a Christian, but this deepened his understanding of what he knew before. He understood the 2009 Fort Hood shooting — he represents the area — but now is more in tune somehow with it. “When they had the shooting in Vegas, I remember one of the persons they interviewed said that they will never forget the sound of those bullets going between those buildings," he says. "I’ll never forget the sound of that gun firing between those pine trees, you know? I’ll never forget that. And you’re just aware of these kids in Florida, what they went through.”

On the field that morning, he said it was a little weird to be back. But he was glad to be there, in the end. It was good.

“It’s baseball,” he said. “Baseball every year in America starts fresh.” ●

Veronica Dulin contributed reporting.