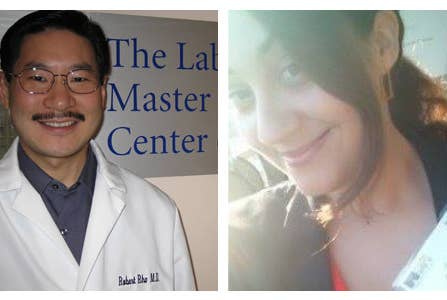

Jamie Lee Morales bled to death on the night of July 9.

Earlier that day, just after 1 p.m., she had an abortion at a women’s clinic in Queens, New York. During that procedure, the Queens district attorney’s office said, the clinic’s owner, Dr. Robert Rho, tore Morales’s cervix, pierced her uterine wall, and cut her uterine artery — all things that are not supposed to happen during a surgical abortion.

The DA said that after her abortion, Morales bled “profusely” in the recovery room, requiring a second procedure. Afterward, she was allowed to leave the clinic, “despite having collapsed and appearing disoriented.” In her sister’s car, Morales “allegedly fell off the backseat and became unresponsive.” At the hospital, on that unusually cool summer night, six units of blood could not save her. She was 30.

Decades after Roe v. Wade, it’s rare to die from a legal abortion in the United States. The CDC’s most recent abortion mortality count comes from 2012, when there were four deaths out of 699,202 reported abortions. More than 600 women in the United States die each year in childbirth or from pregnancy complications, according to the CDC.

It’s even more rare today that a doctor involved in an abortion-related death faces criminal charges — medical malpractice lawsuits are more likely. But in October, four months after Morales’s death, a grand jury indicted Rho on a charge of second-degree manslaughter. If convicted, he could face 15 years in prison.

Rho’s prosecution would be considered highly unusual if it happened at any other point in the last decade. Consider the venue alone: New York, a state historically friendly (or friendlier than most) to abortion and abortion doctors. But Rho’s case carries a new weight now, as Donald Trump and Mike Pence’s ascension to the White House draws an enormous question mark over the future of abortion access, thrusting the abortion debate from its on-and-off dormancy in state legislatures back onto the national stage.

Rho faces trial at the same time many speculate whether Trump’s eventual Supreme Court appointees will, as promised, overturn Roe v. Wade and Make Abortion Illegal Again, returning Americans to an era when many more women died from abortions and many more of their doctors were prosecuted. The coming Trump administration means Rho’s case may not be an anomaly. It could be an accidental harbinger.

“Everybody knows about Kermit Gosnell,” said Carol Sanger, a Columbia University professor specializing in abortion law who’s been honored by the pro–abortion rights Center for Reproductive Rights. Sanger was referring to the Philadelphia doctor who ran a largely unregulated and unsanitary clinic staffed with unqualified employees, who routinely performed illegal late-term abortions, and who left patients dead or injured after procedures. Gosnell was prosecuted, convicted, and, in 2013, sentenced to life in prison without parole.

“But I think the Gosnell case is being milked for everything it could be milked on,” Sanger continued. The reality is that despite Gosnell’s name appearing in nearly every media story since October about Dr. Robert Rho, what we know so far of Rho and his Queens clinic, Liberty Women’s Health Care, hardly aligns with the gruesome tabloid fodder of Gosnell’s “House of Horrors.”

The history of abortion doctors who face prosecution tends to follow this pattern; there have always been doctors who egregiously cross the line into criminal behavior. But other cases are less clear.

“Some abortionists were truly terrible,” Leslie J. Reagan wrote in her book When Abortion Was a Crime, pointing to Dr. Lucy Hagenow of Chicago. Hagenow, Reagan wrote, “caused the deaths of (at least) six women due to abortion in 1896, 1899, 1905, 1906, and 1907 and, after being imprisoned for a number of years, operated on another woman who died in 1926.”

But then there were “long-time, respected, small-town doctors” like Dr. John W. Aiken, “the eminent and only physician for over thirty years in Tennessee, Illinois,” according to Reagan’s book. Aiken was prosecuted for murder by abortion in 1899 after one of his patients died. “Small towns could lose their only physician in cases like these,” Reagan wrote.

Even though getting an abortion was in itself a crime during this time, prosecutors largely enforced the law by going after medical professionals in death cases. Between 1870 and 1940, 43 abortion cases made it to the Supreme Court of Illinois, 37 of which involved a woman’s death, according to Reagan’s book. Reagan did not detail the outcomes of these cases, but she did add that prosecutors weren’t often successful in convicting doctors. That wasn’t necessarily the point — officials hoped arrests and inquests and the scandalous press attention that followed a trial would deter future abortion-seekers.

This strategy took a turn in the 1940s and ’50s. Instead of targeting individual doctors with deaths on their records, prosecutors sought to take down established networks of “trusted and skilled abortionists … that the medical community had essentially endorsed through its widespread referral system,” according to Reagan. In other words, nearly legitimized spaces in which women received safe, albeit illegal, abortions.

After the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973, prosecutions of abortion providers became rarer. In Queens in 1995 — under the same district attorney now pursuing Rho’s manslaughter charge — Dr. David Benjamin became the first doctor in New York ever found guilty of murdering of a patient during a medical procedure, after his 33-year-old patient bled to death following a late-term abortion. Today, it’s more common for an abortion-related death to result in a civil lawsuit, like the one Tonya Reaves’ family settled for $2 million against Planned Parenthood of Illinois after Reaves bled to death in 2012 following an abortion.

In a court document filed the day of Rho’s October arrest, prosecutors said they’ll present at trial a statement the doctor gave to an investigator from the New York State Department of Health four days after Morales’s death. It includes the only description of Rho’s version of the story available to date.

According to the document, Rho told the investigator that Morales’s second-trimester “fetus was smaller than he expected,” but that no complications were identified by the end of her abortion. In the recovery room, though, “vaginal bleeding was observed.” Back in the operating room, Rho repaired a cervical tear, according to the document.

“[After] this intervention, the patient was again monitored in the recovery room where the vital signs were noted to be stable and no further bleeding was observed,” the document said, adding that Morales “was standing by herself and able to walk." Rho told her and her sister to “seek care at a hospital if any further bleeding was noted."

“Usually when a doctor injures or even kills a patient, we consider it to be accidental or malpractice.”

Rho also told the investigator that he knew Morales used her sister’s name to register at the clinic and “that there was an issue with payment for the procedure which was handled by the receptionist.”

At a pretrial court hearing in mid-November, Rho’s attorney, Jeffrey Lichtman, told BuzzFeed News he believed Rho’s case “absolutely should have been a civil matter.”

“This isn't somebody who's known as some kind of miscreant doctor who becomes a butcher,” Lichtman said. “He's well respected and credentialed.”

Looking at Rho’s case, Carol Sanger said she thought “the criminal part is really the unusual part.”

“Usually when a doctor injures or even kills a patient, we consider it to be accidental or malpractice,” she said.

Essentially, there are three types of mistakes that doctors can make. Michael Krauss, a George Mason University law professor specializing in malpractice cases, breaks it down like this: “There’s medical error, and that’s nothing. There’s no liability for an error. Then there’s negligence, or an error that is more than just a technical mistake. It’s something a reasonable person wouldn’t have done. Then there’s the point at which negligence becomes criminal. That point is where carelessness is much more than carelessness.”

A doctor who heads from the pub to the operating room and makes a fatal mistake, for example, calls for an involuntary manslaughter charge, Krauss said. But a doctor who accidentally takes too many of his meds and finds himself doped up during an operation would not likely face criminal charges.

Though he couldn’t speak to abortion doctors specifically, Krauss said obstetricians are uniquely vulnerable to civil lawsuits. As Rho’s lawyer said, abortion is “high-risk, and doctors don't want anything to do with it because they don't want to get sued.”

And Rho, an obstetrician, has been sued: three times for medical reasons, and twice for sexual harassment.

“It is true that a majority of obstetricians do get sued sometime in their career,” Krauss said. “Three times is incontrovertibly more than average.”

“All of a sudden he’s public enemy number one," said Rho's lawyer. "I don't want him to get caught in the maelstrom of this political football.”

In one lawsuit that was settled for $2 million, a woman claimed that Rho performed a failed second-trimester abortion on her in 2008, causing her to give birth to a premature baby with brain damage. A medical assessment of the baby included in the court documents said the child would never be “educated in a conventional classroom without support,” “employed in the competitive job market,” or “able to live independently, and will require lifelong supervision either at home or in a residential setting.” Lichtman, Rho’s attorney, told BuzzFeed News that Rho settled to avoid trial publicity on the advice of his then-lawyer, and that Rho “claims he did absolutely nothing wrong as the patient did not follow his instructions.”

Two other surgery-related lawsuits against Rho were dismissed. In 2009, he was sued for allegedly lacerating and disfiguring a woman’s labia during a cosmetic labiaplasty. (Rho also ran a labia reduction surgery business out of his clinic.) In 2005, he was sued after a woman’s medical abortion was complicated by a left tubal pregnancy that required surgery. In a series of procedures, the woman’s abdominal cavity was cut, causing “extensive internal bleeding” as well as “severe scarring, need for exploratory surgery and the need for a blood transfusion,” according to her complaint.

Twice Rho was sued for sexual harassment. In 2010, a medical assistant alleged in a lawsuit that Rho backed her against the wall of the clinic’s consultation room to “hug and kiss her against her will” on several occasions, including once pressing his erection against her body. He was accused of giving her a free cosmetic procedure so she would accept his sexual advances. In this case, a preliminary conference was ordered, where settlement discussions were conducted. There’s no record of how the case concluded.

In a separate case — which made it in front of a jury, and into the press — a receptionist at the clinic said Rho pressured her for sexual favors after he gave her free liposuction in 2008. He also allegedly told her, “You should be nice to me,” after asking her out for drinks. When she accepted, fearing losing her job, he tried to kiss her “on numerous occasions,” the woman alleged. She rejected his requests to go to Atlantic City or Broadway shows with him, the lawsuit said. Rho was cleared.

Lichtman emphasized that these cases were “unfounded and dismissed," and that Rho "has no pattern of malpractice or negligence in over 20 years of performing abortions, many of which were high-risk.”

Beyond the allegations, only a single line in one document from these five lawsuits reveals anything about Rho’s personality. It’s in a deposition of the woman in the tubal pregnancy case, who said when Rho visited her after her surgery, “Dr. Rho didn’t say much. He’s not a person that talks a lot.”

When the New York Times reported on David Benjamin’s 1995 murder conviction, the paper acknowledged that such cases typically “are played out in malpractice civil suits, but the Queens District Attorney, Richard A. Brown, said that Dr. Benjamin's incompetence and disregard for the patient were so reprehensible that he decided to pursue a murder charge.” No such statement has been released in Rho’s case to explain motivation for the prosecution. When asked why he thinks his client has been criminally charged rather than left to face civil action, Lichtman only shrugged and complimented the case’s lead prosecutor, Assistant District Attorney Brad Leventhal, on his fairness.

“I would never impugn his integrity regarding the decision, in terms of making this a criminal case,” Lichtman said.

"Forget the fact that everybody’s looking for a reason to sue doctors. Now we’re going to start criminalizing one mistake in 40,000?”

There might not be much that a pro– and anti–abortion rights lawyer agree on, but when asked separately for their opinions on Rho — provided with only a few early news articles on his case — Carol Sanger and Teresa Collett, a University of St. Thomas law professor who has represented government officials defending abortion restrictions, had a strikingly similar suspicion: Prosecutors know something significant about Rho that they haven’t publicly revealed.

“There seems to be some big fact that we’re missing that they have,” Sanger said. Criminal prosecution “just seems an unnecessary way to proceed.”

“I think this is an unusual case,” Collett said. “My first question was ‘Huh, I wonder what they’re really looking at.’”

The ideologically opposed women may be on to something: A month after his indictment, on Nov. 11, the New York State Department of Health's Office of Professional Medical Conduct quietly suspended Rho’s license — though he had already shuttered his clinic — after he didn’t contest charges of negligence and failure to maintain records.

According to the board’s report, Rho “performed terminations of pregnancy procedures in an inappropriate manner, under inappropriate circumstances, and/or while failing to appropriately or accurately document such procedures.” While the report makes reference to “more than one occasion,” the Department of Health refused to provide the number of patients involved or the date range of the complaints.

The license suspension “put us in a tough spot,” said Lichtman, Rho’s lawyer. Fighting it might have led Rho to incriminate himself in the criminal case, he said, “and right now we're mostly concerned about saving the man's freedom.”

Today Rho remains free on $400,000 bail and is expected to go on trial next year. His lawyer describes him as a “regular guy” who has done 40,000 abortions, with only this one ending in disaster. “All of a sudden he’s public enemy number one,” Lichtman said.

“He's still a man. He's got a wife. He's got a 12-year-old child. These are human beings involved. And this is a guy who's given good care to women for decades, and to suddenly be vilified as the Antichrist, or satanic — you wouldn't believe some of the things that I've read online,” Lichtman said. “I don't want him to get caught in the maelstrom of this political football.”

Though he said he has empathy for those on both sides of the abortion debate, the defense attorney, who’s represented famed ex-mobsters and rappers, said he doesn’t care what the public thinks about this case.

“All I'm concerned about is the jury,” Lichtman said.

Despite her politics, Teresa Collett doesn’t think an anti-abortion argument would help prosecutors win the Rho case.

“This is a doctor who did not follow standard medical practices in ensuring that his patient could be safely discharged to go home,” she said. “Frankly I don’t think it’s a winning strategy to make it about ‘This is a bad man who kills babies.’”

Particularly in a progressive state like New York, Collett added, “You might as well write the petition for appeal for [the defense].”

"Public exposure of a woman's abortion — through the press or gossip — served to punish women who had abortions, as well as their family members."

Still, Collett admires the sentiment behind the prosecution. “I think no one wants unsafe medical procedures for women, period,” she said. “I’m encouraged that even in New York we see a prosecutor who sees that and is gonna act on it.”

Krauss, the George Mason law professor, agreed that “it would be difficult for prosecutors to succeed if they make it about abortion.” Rho’s jury will likely have people who are pro–abortion rights and anti–abortion rights, he said.

“My guess is prosecutors are going to de-emphasize [the abortion] issue and focus on the death of the mother and behavior of the doctor,” Krauss said. “I think prosecutors are going to say this has nothing to do with what you think about abortion — unless you think abortion doctors should kill their adult patients.”

Krauss pointed out that in medical malpractice lawsuits, doctors “do pretty well before juries ... in part because [juries] like their own doctors and want to believe their own doctors are good at their jobs.”

But in a criminal case, “the state believes it has evidence of really egregious behavior,” Krauss said. “And if it does have such evidence, people are gonna say, ‘This doctor isn’t good. This doctor has got to be locked up.’”

Lichtman said it’s been “anguishing” to watch the “external pressures” of the abortion debate weigh on Rho. The lawyer himself has been getting death threats from abortion opponents, he said — “ugly emails and whatnot.”

“I know that it’s a hot-button issue, and I know that people get very, very emotionally charged, but there’s got to be some level of respect for the law," he said. "What I’m afraid of is that this sort of hysteria is what drives this to become a criminal case."

“There’s a reason why we’re not going to be getting the best of the best to become doctors anymore,” Lichtman continued. “What’s going to happen to the next person who decides whether or not to go to medical school? He’s not gonna go. Forget that their malpractice insurance is through the roof, forget the fact that everybody’s looking for a reason to sue doctors. Now we’re going to start criminalizing one mistake in 40,000?”

Lichtman has a point: Many abortion providers still struggle with the stigma from decades past, when upstanding doctors performed abortions in secret to protect their reputations while less reputable doctors were more open about performing them, Sanger said.

Twenty-five years ago, Leslie Reagan observed that “an appallingly small number of physicians are being trained in abortion,” citing a figure from 1991–1992, when just 12% of OB-GYN residency programs taught first-trimester abortions. “[Young] doctors learn not only that abortion, though legal, is less than honorable, but that they need not listen to the expressed needs of women in particular or patients in general,” said Reagan. The pattern holds today.

There are signs of change. Sanger recalled recently being in a meeting of abortion providers when one in attendance suggested they reclaim the stigmatized term “abortionist."

But this was in the days before President-elect Trump. After Trump, on the state level, abortion providers will continue to face the “picking away of their practices through an endless supply of state legislation,” Sanger said. The Guttmacher Institute’s math puts more than one-fourth of all abortion restrictions enacted since Roe v. Wade in the last five years.

Teresa Collett predicts that more states over the next few years may consider requirements that abortions be performed by doctors, rather than other medical professionals like nurse practitioners, “if there is actual evidence that it’s needed,” she said. Though Rho is a medical doctor, Collett said she thinks his “prosecution helps publicize the fact that there is still a lack of regulation.”

Collett hopes Trump’s first anti–abortion rights initiatives will be relatively quick moves, such as reversing President Obama’s executive orders regarding abortion.

“That’s short of reversing Roe v. Wade, which the administration can and should do, and people who voted for Trump expect him to do,” Collett said.

Some say it can’t be done. But Roe v. Wade doesn’t need to be wiped from the books for a seismic shift to occur in abortion law.

Without being overturned, “Roe v. Wade may be so thoroughly gutted by judicial and legislative action that it will be meaningless,” Reagan wrote, pointing to justices upholding Roe on “thin grounds” in 1989 and 1992. “Making abortion hard to obtain will not return the United States to an imagined time of virginal brides and stable families; it will return us to the time of crowded septic abortion wards, avoidable deaths,” she wrote.

More restrictions, by Reagan’s logic, mean more Robert Rhos and more Jamie Lee Moraleses. And that reality does not depend on overturning Roe v. Wade.

Carol Sanger predicted that Trump’s first big swing at restricting abortion might not center on Roe v. Wade, but rather Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the 1992 case that — while upholding a woman’s constitutional right to abortion — opened the door for new restrictions to come “flooding out ... in all the pro-life states,” Sanger said. But in June, a Supreme Court ruling limited state lawmakers' ability to introduce abortion restrictions that purport to protect women without sufficient factual evidence.

The Trump administration, Sanger said, could try to undo the June ruling, urging the court to go back to the Casey era — a move she said would cause “almost equal damage” to overturning Roe v. Wade for those seeking and providing abortions.

Liberty Women’s Health Care isn’t there anymore. Once operating from the top floor of a breathtakingly boring four-story Charles Schwab building in Queens’ bustling Flushing neighborhood, nearly every sign of the clinic’s existence has been wiped away. A mailbox might have the faint outline of “RHO,” but his and the clinic’s name have been purged from the building directory. A banner now hangs on the outside of the building: “SPACE FOR LEASE,” boasting 2,870–5,740 square feet for “office/medical.”

Today the only traces of the clinic live online. There’s a commercial on YouTube — essentially a slideshow of stock images of other doctors' offices. The clip ends directing viewers to saferabortion.com, a dormant domain once owned by Rho. Memories of visits to the clinic are scattered across review websites. Some reviews are broad and positive. Some are very long, specific, and scathing. This is not uncommon for busy New York City doctors' offices.

Jamie Lee Morales’s family and friends did not respond to requests for comment. We don’t know how she first came across Liberty Women’s Health Care. We only know she was living upstate but had family in the Bronx, including a sister, who came with her to the appointment. Sanger called Morales’s decision to use her sister’s name at check-in “interesting.”

“It doesn’t in any way relate to [Rho’s] possible malpractice, but what it shows is how secretive women still are about having a legal procedure,” Sanger said. “She didn't want any record attached to her.”

“I don’t know that any of it matters,” Lichtman said when asked about Morales’s false identification, and about how much of her background he plans to bring into his defense of Rho. “I'm not here to smear this woman. It's a tragedy what happened to her already. I've got great empathy for her, it's awful.”

In the early 20th century, the press would publish “names of women who had illegal abortions and the intimate details of their lives periodically,” wrote Leslie Reagan. “Public exposure of a woman's abortion — through the press or gossip — served to punish women who had abortions, as well as their family members … Doctors observed that even when a woman died after an abortion, families did not want authorities to investigate because they wanted ‘to shield her reputation.’”

Despite abortion legalization, not much has changed. Morales’s name hit the New York City tabloids and the Times following Rho’s indictment, her photo published in the New York Daily News. Her family has not yet spoken out publicly on the case.

Like Rho’s clinic, memories of Morales live on, fragmented across the internet. There’s her professional Facebook account, where she promoted her company — the same company that, according to a GoFundMe page, donated $2,000 to her funeral. That GoFundMe offers the clearest picture of Morales as her friends remember her. She’s described as “intelligent and vibrant,” passionate for her causes, intellectual and funny. She loved Batman and named her dog Harley Quinn. She struggled in secret with lupus. Her LinkedIn says she studied psychology at the College of New Rochelle and volunteered in Haiti with the Archdiocese of New York.

Then there’s her personal Facebook, where she declared herself a “Berniecrat,” changing her profile picture to an upside-down American flag three days before her death. Two years ago, she posted a video of herself from that account chiming in on “the human experience.”

The nine-minute video shows Morales, voluminous curly hair and black-rimmed glasses in a dark room, talking about how she aspires to be seen as “an adult who is contributing to society, who is helping their fellow man.” She’s clear, energetic, a motivational speaker calling out women who judge other women based on appearance and teenagers who are obsessed with their phones. She urges everyone to return to their “humanity.” She might not have known that her loved ones would turn to this video after she died, sharing it and adding comments like “rest in peace.” But her messaging couldn’t have been more on point.

“Enjoy the human experience, because supposedly, depending on what religion you subscribe to, or which spiritual belief you subscribe to, you only get one,” Morales said. “Materials, likes, followers, ‘Instagram famous,’ ‘Facebook famous’: None of that you can take with you. We’re all balls of energy — and energy, the cool thing about it is it never dies. It transfers into something else, into another form.”