One April afternoon in 2004, my father phoned my sister, Laurie, who phoned me to say our mother had lost her marbles. She hadn’t eaten for weeks; couldn’t stop crying.

“She’s drinkin’ lots of wine,” he told Laurie. “From the box!”

As a man of few words, our father seldom admitted to the state of his own helplessness. Yet here he was, flummoxed by our mother’s sudden sea change. I called her. Between wails she alluded to, I think, my father’s infidelity.

Though I never got along with him, my father did not strike me as the cheating type. Such secrecy appeared beyond his means. Once, when Laurie wanted to travel to Paris to visit a boy she loved, my father snuck into her bedroom, took her plane ticket, and hid it under a rock in the backyard. His subterfuge did not last long. The next day, he returned the ticket to Laurie, dusty as it was, declaring his disapproval, which was his way of acknowledging that he did not ultimately wield the power to circumvent the truth — he could not stop her.

According to my sister, my father staunchly denied any accusation of an affair. Why, then, was my mother starved and drunk? She’d abandoned her stalwart trifecta, her bastions of normalcy: She did not clean, did not attend church, and did not eat. Over the phone, she divulged no further details either, and merely wept for the duration of our calls. Seeing no other solution, my sister and I flew to southern California for a family intervention.

After the 35-minute drive west from LA/Ontario International airport, Asian suburbia greeted me: boba cafés, a Korean tofu house, Korean BBQ restaurant, Korean church (not ours), Korean sauna, and a Korean supermarket. My sister then took us to the top of a hill, where the city dropped away, revealing a mosaic of rooftops, and we entered our parents’ community of homes — a place called Vantage Pointe.

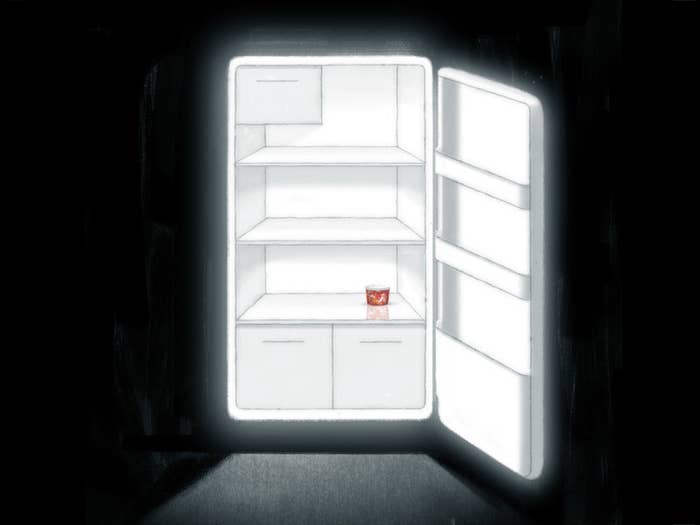

It was a balmy 80 degrees outside, but a stale chill hovered in my parents’ house. Before sitting down to confront our mother, we waited for an unnamed fifth person to join us. I occupied my time by inspecting the fridge. Its racks — ordinarily packed full with Korean vegetable side dishes, or hot dog stir-fry, or a pot of tangy mung bean stew — were empty, save for a lone Tupperware of kimchi. The rice cooker sat dormant on the kitchen countertop. Beside it was my mother’s sole sustenance for a month: boxed Franzia merlot.

The mystery guest, a Korean man I’d never met before, finally arrived and joined my sister and me on the couch. He appeared no older than 40, and was visibly perspiring in his three-piece suit.

“Who’s he?” I asked my mother, pointing to the man.

“He is our pastor, at church,” my father answered.

The young pastor smiled feebly, offering a hand to shake, which I rejected with the comfortable petulance of a child (I was 20). His presence offended me. The pastor I’d grown up with, Reverend Lo, had recently retired. Not that I’d want him there either — this was a family affair. But my father believed that having an intermediary, a spiritual guide even, might help jostle my mother into clarity.

She sat silently in a plush armchair, postured like a skittish, lost cat. A coffee table divided her from my father, who sat in a matching plush armchair, his bare feet crossed at the ankles. Bright light reflected against the table’s glass inset, revealing a thin layer of dust. The mother I left here last Christmas would have cringed at such an oversight. But that woman was gone.

Whatever it was that gripped her seemed bigger than us, the living room, the house. She’d dropped to a skeletal 90 pounds; ghostly thin, but electric with grief. Her eyes, nearly swollen shut, were cracked open just enough for her to gaze off to some unknown, faraway place. Trembling and hyperventilating, she looked alive and dead at the same time.

Five months prior, I found my mother in the same living room, hand scrubbing the hardwood floors. This act, in and of itself, was not unusual (she never could trust the efficiency of mops). But what struck me was how uncharacteristically peppy she appeared, her trademark scowl softening as she swiped a towel across the wooden slats in brusque, vigorous circles.

When the timer bleated on the kitchen oven, she rose from the floor, calling out in a singsong voice: “Quich-ey! Quich-ey!” The mini ham-and-cheese quiches were done. Next, mini cheesecakes, mini pecan pies, followed by the mini wonton cups filled with cherry custard — all her favorite party-pleasing recipes she’d clipped over the years from Better Homes & Gardens.

“Do you need help?” I asked. She waved me away with one hand, shimmied the pan out of the oven with the other, satisfied, it seemed, with the busy rhythm of her work.

In a few hours, the parents of the Korean Presbyterian Church of San Gabriel Valley would arrive at our front door for a first-ever, black-tie Christmas fete. My mother had organized the event on her own: snack table provided by herself, dinner catered by Mai Tong (a nearby Thai restaurant), and music courtesy of two local Mexican DJs. She’d stocked the fridge with six rows, six cans deep of Miller Genuine Draft, as if prepped for a frat rager. On the counter, bottles of Kendall Jackson chardonnay, purchased in bulk from Sam’s Club, sat at room temp, alongside a motley crew of Jose Cuervo, soju, and Bailey’s Irish Cream.

My mother’s sole sustenance for a month: boxed Franzia merlot.

Laurie wouldn’t arrive until Christmas Eve, but I was home early, on winter break from college in New York. Two years prior, my dream school had admitted me through what I considered a loophole: cinema studies. Despite my middling GPA, I’d written a convincing 10-page portfolio paper on Italian neorealist film — a subject of which I knew very little — and got in. Sadly, in class, I floundered. It turned out my mind was not particularly pliable to film theory compared to my peers, who could easily debate the gravitas of diegetic versus non-diegetic sound in early talkies; a topic that, at best, offered the perfect monotone soundtrack and dim lighting for the most expensive naps I’ve ever enjoyed in my life. But I’d achieved my primary goal: distance, or the illusion of it anyway. Three thousand miles separated me from my mother, whose constant, miserable disposition I could no longer stomach. We'd been close once, when I was a little girl, but something had shifted in my teenage years until one day I realized, with searing clarity, that my mother was a locked door. While I often wondered what she wanted from the world, what she felt she was missing, I’d understood too how such answers seemed impossibly off-limits.

In my absence though, it looked as if my parents’ unhappy marriage had finally reached a new equilibrium. Before I’d arrived, my mother mentioned over the phone how she’d recently learned to appreciate my father’s company, the closest I’ve ever heard her hint at the potential of any kind of love between them.

But it’s true what they say, about the calm before a storm; an eerie kind of stillness like that is not meant to last.

I’ve since returned to that party many times, examined the moments and hours over and over in my mind, wondering how I’d missed the clues of her state of change. She’d seemed in good spirits that day and had even permitted me to film the entire evening. Something about a bunch of boozed-up, religious Korean folks dancing around in tuxedos and dress socks seemed utterly absurd, so I’d wanted to turn the whole thing into a documentary. A tasteful, vérité type deal. I never made the film, but I’ve reviewed the tapes countless times. It’s strange to think how even then I’d understood the value of what would take place, how that evening needed to be captured and recalled later for a reason — though I did not know yet why.

12/19/2003. TAPE 4

My father enters the kitchen in a white tux, red cummerbund, and matching red bow tie, gives a twirl, hands splayed, as if to say, Wouldya get a load of this! My mother doesn’t acknowledge his entrance, and continues to flit about, completing final touches for snacks and refreshments. She’s wearing my sister’s homecoming dress from 10 years before, a slim, strappy black number with a fan of silver beads stitched across the chest. Though it’s a size 4, it’s loose around her waist. She slices lime wheels for the tequila. Beside the full rice cooker, a large stainless steel coffee urn sits brimming with roasted corn tea. The small kitchen table, where we dine every night, displays my mother’s baked goods along with a pyramid of nickel-sized glazed meatballs perched on a romaine leaf, and a three-tiered tray packed with fudge squares, coconut rolls, and a plate of Dove dark chocolates. Whole oranges and napkins designed with cartoonish poinsettias lay tastefully scattered. In the next room, the long, special-occasion-only dining table, is spotless with a pinecone/never-been-lit candle centerpiece placed beneath the tinsel-lined chandelier.

It’s true what they say, about the calm before a storm; an eerie kind of stillness like that is not meant to last.

This never-been-used theme is common with my mother’s décor choices, a sort of permanent staging of the house, as if always ready to show the space to potential buyers, as if no one really lives here. The Christmas tree in the living room is plastic, which my mother has insisted on assembling and decorating on her own each year. She prefers a plastic tree because she can control its life: She decides when to erect it, when to take it down; it never dies, and the clean up is easy. She does not let us trim the tree with her either. She needs the golden and green globes distributed evenly beside the glittery strawberries and tiny wreaths. She reserves some sentimentality though: Year after year she points out the ornaments that are older than I am, insisting on hanging the popsicle sled I made in ’89 at the front of the tree. She also places the same light fixture in my bedroom window every holiday season: a large glowing candlestick that she does not realize bears an uncanny resemblance to an erect penis. This "candledick," as well as the bow that tops the tree, stays lit at night even when everyone sleeps. The beautifully wrapped fake presents that line the tree skirt wait expectantly for no one.

Guests begin to arrive. The choir director, the Chungs, the Lees, the other Lees. Rather than calling them Mr. or Mrs., we identify them by whose parents they are, according to their children’s American names: David’s father, Linda’s mother, Bryan’s dad. Each person removes their shoes at the doorway and treads across the Berber carpet in nylons and socks. Bottles pop. Room temp Kendall Jackson is divvied into small plastic cups. The ladies nibble at the snack table. They cheer upon the arrival of each new guest, oohing and ahhing, doting over fancy dresses and shawls. The men stand and sip wine in silence. The general vibe is restrained contentment. This is new, to socialize this way outside of church, imbibing alcohol, dressed to the nines yet somehow newly naked, shy. No one is drunk enough at this point in the night. Eric Carmen’s “Hungry Eyes” plays from a cable TV channel on the big screen.

“Tonight is Western theme!” my mother announces in English. She means American — they know this. She’s learned how to make American snacks, throw an American party; they’ve arrived in American clothes, will dance to American music.

“Western?” my father says. “You mean…cowboy?!” Which gets a laugh.

Since this is a church function, Reverend Lo must legitimize the gathering by delivering a short sermon. Festivities pause, though my mother continues setting up the buffet in the background. Everyone else prays, and I film their bowed heads, closed eyes, fervent ahhhhhmens, paying close attention to their socked feet — I decide this is an important theme. I film, all told, probably an hour of socked feet, crossed at the ankles, dangling from tall chairs. Something about the humble, hooded shape renders each guest, my father included, a touch childlike, even vulnerable.

Cut to: Pad Thai steaming in wide foil trays along the kitchen countertop, enough for a crowd of 100. At most, there are 20 people in attendance.

They feast as Kenny G’s “Forever in Love” moans in the background. My parents work as a team, opening more bottles of wine, passing or topping up glasses, all while never speaking to each other. Mom piles heaps of noodles and salad onto plates, just like on the assembly line for Sunday post-service lunch. As with any other family gathering, like Thanksgiving or 4th of July, she keeps moving, and I never see her eat.

My father takes drink orders, announcing in Korean: “We have Bailey’s Irish Cream, we have everything.”

“Ice cream?” says David’s father.

“No, Eye-dish koo-dee-muh,” my father says. “On the rock!”

Eager to share, he dips back into the kitchen. My father breaks the rules though, by fumbling around in the cabinet for a real glass. My mom catches him and shrills: “Just use the cup!!!” and passes him plastic. She’s the one who washes the dishes at the end of the night. He sneaks away with the real glass anyway, grinning, like a kid stealing candy.

DJ Anthony and DJ Marco, two middle-aged Mexican dudes, set up their four-foot high speaker sound system in front of the Story & Clark piano I never successfully learned how to play as a child. They wave to my camera and survey the crowd, bemused. My mother fetches them two cans of MGD, then totters her way back to the party. I’ve never seen my mother drunk, never seen her drink, but tonight she’s sipping Chardonnay on an empty stomach.

TAPE 5

Disco lights speckle frenetic rainbows across my mother’s spotless hardwood floors. I didn’t think I’d ever hear bachata blaring in this house, and yet here we are, güira scraping, bongos thumping, a distinctly Latin rhythm that, besides my father and the DJs, no one else appreciates. My Korean father is fluent in a Mexican dialect of Spanish. His favorite beer is Tecate. He sleep-talks in Mexican slang (¡Dale cabron!…¡No manches!). He even prefers Mexican music. His favorite singer is crooner Luis Miguel. Earlier that day, as we drove around looking for party supplies, he’d played on repeat the ballad Te Extraño. I’d filmed him holding the CD booklet open against the steering wheel, zoomed in on his eyes darting back and forth from traffic to lyrics. He’d lagged a few beats behind, but trilled his R's melodically in perfect Spanish to the sweeping score.

At the party, the dance floor stays empty until a remix of Chubby Checker’s “Let’s Twist Again” peals from the speakers. Linda’s mom rallies guests onto the dance floor. Shawls are discarded. Socked feet scuttle. Now, well lubricated, everyone dances. My father champions a side-to-side T-rex arm movement. Linda’s dad, obedient to the song, twists. One woman performs a kind of jazzy calisthenics, pounding her fists against her stomach. I’ve never seen my mother dance, never seen her lose control. She runs in place, pointing her fingers to the beat, as if to say, You! You! You! Her head bobs back and forth like a ragdoll. A DJ says, “Everybody scream!”

No one screams.

He tries again: “Everybody…scream!”

The crowd cheers, but my mother shrieks, giving us a startling, throat-clearing screech, then keels over cackling. Breathless with laughter, she escorts herself out of the room.

My parents don’t dance together. They cajole other couples onto the dance floor, while hooting and hollering. They form the bridge, hands linked, for the party train to pass through, but my mother soon tires of this and slips away from my father to perform her favorite dance move, one which calls for the frantic grasping of air, palms opening and shutting with springy, robotic flourish. A request is granted and a traditional Korean song plays, perking up the wallflowers. This instantly soothes the crowd, too. It’s a song they all know from childhood, and at the end of each musical phrase they shout in unison, “Cha-cha-cha!”

Then “La Bamba.” Then “Oye Como Va.” Then “I Will Survive.” Then the “Macarena,” to which no one knows the corresponding dance. My mother continues to scream intermittently which is, to her, the joke that keeps on giving. She screams until she is red in the face, cackles, clutches her stomach, then winces from the curious mixture of pain and pleasure.

Later, I catch her dancing alone, eyes closed, swaying and smiling, mouthing the lyrics to the Bee Gees’ “Stayin’ Alive.” This is the kind of conviction she shows while leading Praise Team in Sunday service. This is the closest I’ve seen her to happy.

“Are you drunk now?” I ask my dad.

“Maybe!” he says, smiling wide, like the Cheshire Cat.

They count down to the New Year a week before Christmas, two hours before midnight. When they finish, there are no kisses or confetti or streamers or party horns, just a round of applause for one another. They did it. They made it to 10 p.m.!

After exultations and well wishes, the ladies chit-chat around the snack table about next year’s theme. Like always, I recognize the sound and cadence of their speech, but only English words surface from the tangle of Korean phrases. “Something something bobby socks-uh! Something something poodle skirt!”

No one knows there won’t be a party next year.

In the living room, I watched the young Korean pastor’s socked feet dangle above the carpet many minutes before asking my mother: “Why is he here?”

“We are all here to help your mother get healthy,” the pastor said.

“So, well...” my sister ventured. “What happened?”

“She’s crazy!” my father shouted.

The pastor cleared his throat, called my mother, in Korean, by her church name. Elder Choi. “It’s time to be reasonable. For your children.”

A silence settled over us, disrupted only by my mother’s resonant panting. She could no longer cry but her body shook, begging for air.

No one knows there won’t be a party next year.

“Look,” I said, turning to my father. “Are you having an affair or not? That’s why she’s not eating.”

“It’s all in her head,” he said. “I told her I wasn’t, but she won’t listen.” He waved his hand, exasperated, in my mother’s direction, as if to say, Who do you believe? Just look at her. My mother did not protest.

“Are you even listening?” Laurie asked.

“He’s telling the truth,” I said.

Of course, he wasn’t. The young pastor knew that as well. So did everyone at church: David’s mom, Linda’s dad, all the parents, their children, the choir director, the Praise Team, and the retired pastor, too. They’d come into her home, drank her wine, ate her snacks. They’d heard her scream. Then, they allowed her to wither away week to week. Here, now, we were trying to convince her that she’d lost all that she had left: her mind. And she took it, staring off vacantly beyond us, her children, the man she married, the messenger from God, because she knew, in the end, she was alone.

This isn’t on the tapes, but before DJ Anthony and DJ Marco packed up their gear, I remember my father held everyone hostage via an unsolicited serenade. He broke out his Luis Miguel CD, held the booklet lyrics in one hand, microphone in the other, and belted out his favorite song, Te Extraño. My mother helped pack to-go bags of food for guests in the kitchen while he sang. The DJs watched my father, dumbfounded.

I recently looked up the lyrics to his song and listened again, exhuming his voice from memory. Te Extraño, “I Miss You.” Miguel is wrecked in this one. Inconsolably heartsick. When he cries, when he laughs, when he walks, with every lonely step, if the sun is shining, if snow is falling, he can’t sleep, he’s dying, by God it hurts, because “you can’t imagine, Love, how much I miss you.” He even admits that he doesn’t have a clue how to fix things. “…With all your errors,” he sings, “for whatever you’d want, I don’t know, but I miss you…” I have never heard my parents say to one another those words: I miss you.

I don’t know why my father sang that song in front of everyone, or for that matter, why they threw the party in the first place. Over the last 14 years, I’ve played and rewound the videotapes from that night maybe 100 times — my private ritual (a curious mix of pain and pleasure). No discovery could change the outcome, but I’ve scrubbed through the stock for hidden clues, anyway, hopeful for some new revelation. I’ve studied my father’s eyes as he sang his love song in the car. I’ve searched for knowing glances between church members, or I’ve paused on a frame, to linger on my mother’s private moments: her contorted face mid-scream, her blissful closed eyes as she swayed on the dance floor alone — keyhole glances into her life, beyond the locked door.

Mostly, I’ve watched the footage because it stands as the only remaining artifact, what photos and memories have failed to prove: For one night, my parents were together and happy. The picture quality has dulled over time, the satiny sheen of my father’s red cummerbund nowadays tinged grainy and gray. But it’s all I have left of him, them.

After we left her that April, post-intervention, my mother started spending time inside her bedroom closet. I imagine how she stared up at the stucco ceiling through many sleepless nights. Maybe she passed out against her sweater sets, from too much Franzia merlot. Or, maybe her body went limp from the sheer exhaustion of her sorrow. I could see how my father, mute and dumbstruck, might have appeared intermittently, like some specter, haunting the closet doorway in the dark.

Ten years later, when I turned 30, my mother asked me over the phone: “Could you imagine ever feeling so sad, to end your life?”

“I can’t,” I lied.

We retreated to our own thoughts for a moment, silent, but not yet ready to hang up.

Then my mother told me that one night, in the closet, she swallowed a fistful of pills. I wanted the answers to countless follow-up questions — Which pills? How many? Had she really wanted my father to find her that way? Did she leave a note? If so, what did it say? — but I did not press. With a simple string of words, she told me everything I needed to know.

“What happened?” I asked.

“I woke up,” she said. ●