The morning of Oct. 9, a few minutes into an early-morning workout, the Rev. Al Sharpton stopped what he was doing and pulled out his phone.

He’d heard on TV that ESPN suspended Jemele Hill for two weeks. Sharpton needed to hear what she had said that apparently violated the broadcaster’s social media policy. “If you feel strongly about JJ’s statement,” Hill had written late the night before about the Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones, “boycott his advertisers.” Sharpton was furious.

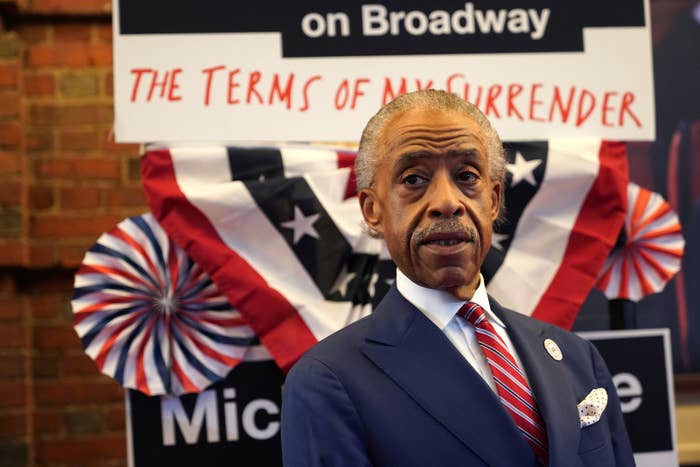

The next day, he stepped out of a black SUV and sauntered toward a cluster of microphones where he demanded answers. “We found the suspension of Jemele Hill to be outrageous at best, and insulting, in fact.” (Sharpton later diagnosed Jones, 75, with a “slave mentality” for threatening to sit his players who demonstrate during the anthem.) Hill’s mother was grateful; she called to thank him.

“It seems like we’re coming very close to normalizing corporations being able to say, ‘Whatever opinion you have, you’re not allowed to speak,’” he told BuzzFeed News, explaining his decision to get involved. “And I thought that was outrageous. It went back to my whole life of seeing them do everything from silence Muhammad Ali and threaten him with jail, all the way to when LeBron and ‘nem were attacked for wearing hoodies. And I said that if no one is going to stand up on this, I am. Because this is crazy.”

That intersection between politics and sports is rawer than it’s felt in a long time. Hill is since back on the air, but her criticisms of President Trump and the NFL feel unresolved, and just one in a series of cultural battles involving everything from race to policing to patriotism, which Trump often starts or stokes. Sharpton mostly dismisses Trump’s tweet about Hill (the president said ESPN’s ratings were plummeting because of people like her). He contends Trump’s real intention was to present her as a trophy to his base, a cue that he’ll “spank and chastise anybody that gets out of line.” “So it was Jemele that week,” Sharpton said. “It was Maxine Waters two weeks before. It became Frederica Wilson two weeks later and even the widow of a dead sergeant. He uses trophies, particularly women — and part of it is a challenge to our manhood: Are we going to stand up for our women?”

What Sharpton wants to impress on people, particularly young black activists, is that the intersection between sports, politics, and media is old. Jackie Robinson is universally revered now, but, Sharpton notes, he wrote in his autobiography, "I cannot stand and sing the anthem. I cannot salute the flag; I know that I am a black man in a white world."

Sharpton — a master of reinvention, enmeshed now in decades of political activism — is often a player in the stories he tells. He recalled the time Muhammad Ali and his protege James Brown brought him on late-night television to talk about the youth movement, and how, during the (infamous) Tawana Brawley case, Mike Tyson visited her at home. He said Houston Texans owner Bob McNair’s comments about not letting the “inmates run the prison” were “very clearly representative of the attitudes of the owners” and that it reflects the broader criminalization of young black men already pervasive in society that has led to mass incarceration.

“Why would you even on a subliminal level use the term ‘inmates’ as an example of running the penitentiary, so to speak?” He saw the impact LeBron James and the Miami Heat had when the whole team wore hoodies in solidarity with the movement behind Trayvon Martin. Same with Eric Garner and the “I Can't Breathe” movement when they wore the t-shirts at Barclays (Sharpton was involved, but declined to get into details).

Protest that comes from the sports community “says to mainstream middle Americans that this is not just the people that they consider usual suspects” that care about civil rights, Sharpton says. “These are people that they actually purchase tickets to see, that they admire, and whose jerseys they wear. It gets a whole kind of different reaction to Americans that thinks this is only the left or the civil rights guys when it's the guys that they look up to saying, ‘No, this is a problem.’” He remembers, for instance, when Rev. Jesse Jackson took him and his mother to Robinson’s Stamford, Connecticut, home. Sharpton was just a little boy. “It didn't mean to me what it meant to my mother.”

Sharpton’s foray into the Hill sports issue is the perfect amalgamation of past efforts he’s undertaken, though: a black woman under attack, a president with whom he has feuded, a threat to go after advertisers, and an attempt on behalf of the wealthy and powerful to silence athletes who are openly demonstrating to bring attention to police misconduct to communities of color. In 2007, he threatened a boycott of advertisers if radio talk show host Don Imus wasn’t fired after he called the Rutgers women’s basketball team “nappy-headed hoes.” He called the Hill suspension “crazy” and said he wanted young people in NAN to think that sports issues are as important as any other issue, even if they’re not a matter of life and death. “No, this is not Sandra Bland,” he said grimly. “This is Jemele Hill. But it is a civil rights issue.”

“What he’s trying to accomplish is the inverse of what we did with Imus,” Kirsten John Foy, a top Sharpton lieutenant, told BuzzFeed News. “We’re using the leverage that we may have with advertisers with outside pressure to say there will be a price to pay if she goes as opposed to saying that there will be a price to pay if Imus stays. It’s pushing the same pressure points and I think they’ve been cautiously willing to engage.”

“Maybe,” he said, someone would “put me on a couch and [sticking up for Hill] is me reacting to how my mother raised me by herself, I don't know. But that we leave our black women out there standing unprotected and not spoken up for is always been a thing that I’ve been something that I’ve been concerned about.”

These days, Sharpton’s got plenty of other concerns, though: He led two high-profile marches and this week hosted a legislative meeting in Washington, which was set to include briefings by Sens. Chuck Schumer, Elizabeth Warren, and Cory Booker, and Reps. Hakeem Jeffries and Barbara Lee. Sharpton will meet next week with ESPN President John Skipper, National Urban League President and CEO Marc Morial, and Melanie Campbell, head of the National Coalition on Black Civic Participation. He's writing a book. He just gave his daughter away. He recently sat, cross-legged, in the front of a day of retrospective panels about his career in the movement. (“It was almost like being alive at your own funeral,” he later told BuzzFeed News.) MSNBC just re-upped his PoliticsNation with Al Sharpton contract for another two years. Gleefully, he talks about two specials for the network, one of which, he says, will be on the 50th anniversary of the King assassination. The civil rights museum project that he wants in Harlem still animates him, too; why, he asks rhetorically, is the nation’s history of the civil rights struggle memorialized mostly in the South?

Sharpton is still fixated in part on Trump; he said he was triggered by the apparent suicide of a white man, Jon Lester, who 30 years ago led a group that chased a young man into the street. He was called a “nigger” and hit by a car as he fled an angry white mob. It brought Sharpton back to a tenuous point in his career. “But it is not lost on me,” wrote Sharpton, “that a Queens resident, not too far from Howard Beach, who never spoke up during that time is now President of the United States.”

Sharpton’s got a slightly different perspective of the man, evidence of years of observing his fellow outer-borough foe, who was also shaped by New York media. Earlier this year, Sharpton recounted to BuzzFeed News a conversation he had when Trump called him after catching an appearance on cable news. “You know that we’re going to have a fight,” Sharpton said he told Trump. “I said, ‘I know you’re not a pushover, but you know that I’m persistent and I’m not just going to stop.’ [Trump] said ‘Well, yeah, well, we’re gonna fight. I just wanted to call.’ And it ended like that.”