Facebook has placed a high-stakes — and, experts say, unwise — bet that an algorithm can play the lead role in stanching the flood of misinformation the powerful social network promotes to its users.

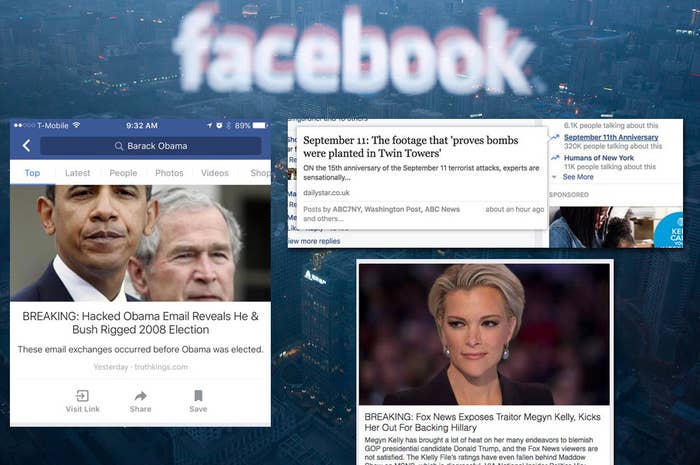

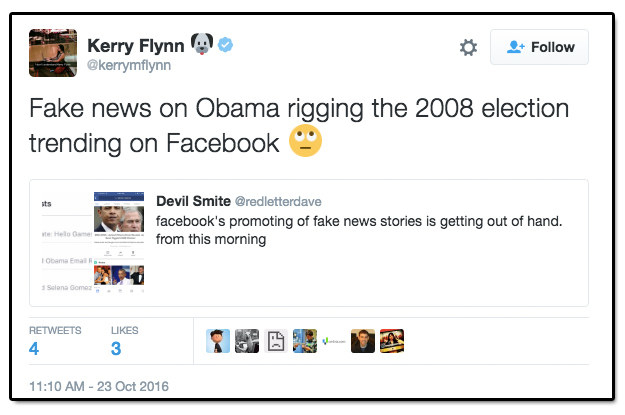

The social network where 44% of Americans go to get news has in recent weeks promoted in its Trending box everything from the satirical claim that Siri would jump out of iPhones to the lunatic theory that Presidents Bush and Obama conspired to rig the 2008 election. As Facebook prepares to roll out the Trending feature to even more of its 1.7 billion users, computer scientists are warning that its current algorithm-driven approach with less editorial oversight may be no match for viral lies.

“Automatic (computational) fact-checking, detection of misinformation, and discrimination of true and fake news stories based on content [alone] are all extremely hard problems,” said Fil Menczer, a computer scientist at Indiana University who is leading a project to automatically identify social media memes and viral misinformation. “We are very far from solving them.”

Three top researchers who have spent years building systems to identify rumors and misinformation on social networks, and to flag and debunk them, told BuzzFeed News that Facebook made an already big challenge even more difficult when it fired its team of editors for Trending.

Kalina Bontcheva leads the EU-funded PHEME project working to compute the veracity of social media content. She said reducing the amount of human oversight for Trending heightens the likelihood of failures, and of the algorithm being fooled by people trying to game it.

“I think people are always going to try and outsmart these algorithms — we’ve seen this with search engine optimization,” she said. “I’m sure that once in a while there is going to be a very high-profile failure.”

Less human oversight means more reliance on the algorithm, which creates a new set of concerns, according to Kate Starbird, an assistant professor at the University of Washington who has been using machine learning and other technology to evaluate the accuracy of rumors and information during events such as the Boston bombings.

“[Facebook is] making an assumption that we’re more comfortable with a machine being biased than with a human being biased, because people don’t understand machines as well,” she said.

Taking Trending global

Facebook’s abrupt doubling down on an algorithm to identify trending discussions and related news stories has its roots in the company’s reaction to a political controversy. In May, Gizmodo reported that the dedicated human editors who helped select topics and news stories for the Trending box said some of their colleagues “routinely suppressed” news of interest to a conservative audience. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg convened an apologetic meeting with conservative media leaders. Three months later, the company fired the editors and let an algorithm take a bigger role with reduced human oversight.

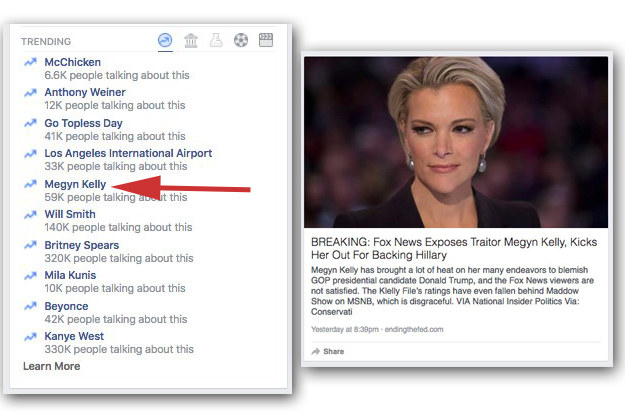

Two days after dismissing the editors, a fake news story about Megyn Kelly being fired by Fox News made the Trending list. Next, a 9/11 conspiracy theory trended. At least five fake stories were promoted by Facebook’s Trending algorithm during a recent three-week period analyzed by the Washington Post. After that, the 2008 conspiracy post trended.

Facebook now has a "review team" working on Trending, but their new guidelines require them to exercise less editorial oversight than the previous team. A Facebook spokesperson told BuzzFeed news theirs is more of a quality assurance role than an editorial one. Reviewers are, however, required to check whether the headline of an article being promoted within a trend is clickbait or a hoax or contains "demonstrably false information." Yet hoaxes and fake news continue to fool the algorithm and the reviewers.

Facebook executives have acknowledged that its current Trending algorithm and product is not as good as it needs to be. But the company has also made it clear that it intends to launch Trending internationally in other languages. By scaling internationally, Facebook is creating a situation whereby future Trending failures will potentially occur at a scale unheard of in the history of human communication. Fake stories and other dubious content could reach far more people faster than ever before.

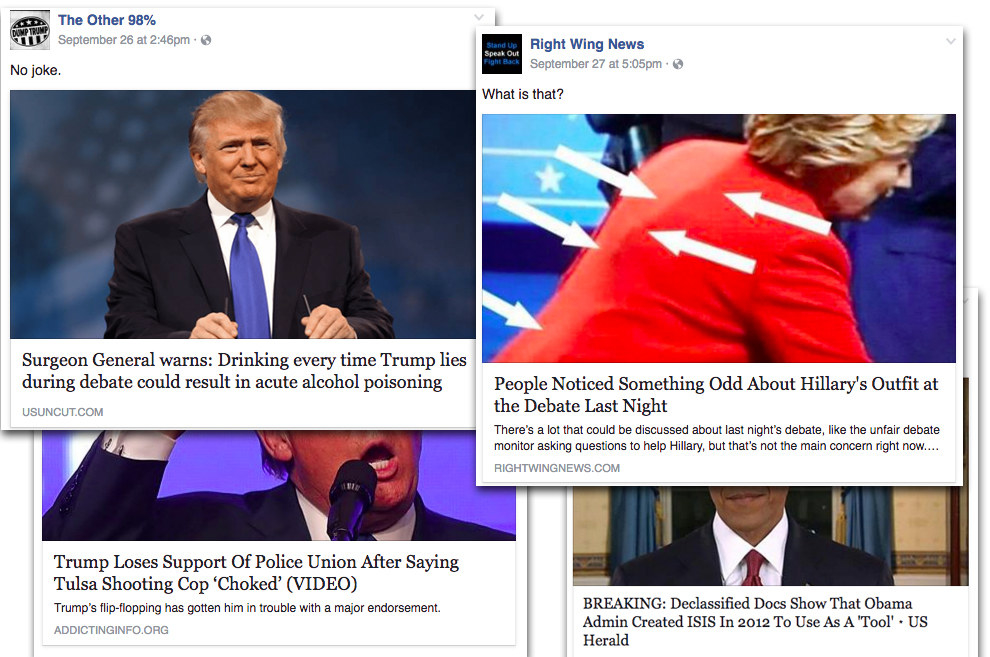

For Trending to become a reliable, global product, it will need to account for the biases, bad actors, and other challenges that are endemic to Facebook and the news media. Put another way, in order to succeed, the Trending algorithm needs to be better than the very platform that spawned it. That’s because fake news is already polluting the platform’s News Feed organically. A recent BuzzFeed News analysis of giant hyperpartisan Facebook pages found that 38% of posts on conservative pages and 19% of posts on liberal pages featured false or misleading content.

Facebook’s challenge with fake news has its roots, of course, in the platform’s users — us. Humans embrace narratives that fit their biases and preconceptions, making them more likely to click on and share those stories. Mark Zuckerberg acknowledged this in a Facebook post marking the 10th anniversary of News Feed.

“Research shows that we all have psychological bias that makes us tune out information that doesn’t fit with our model of the world,” he wrote.

Facebook relies primarily on what humans are doing on Facebook — likes, shares, clicks, et cetera — in order to train the Trending algorithm. The company may have ditched its editors, but we humans are still giving biased signals to the algorithm, which then mediates these biases back to an even larger group of humans. Fake news stories keep trending because people on Facebook keep reading and sharing and liking them — and the review team keeps siding with the algorithm's choices.

As far as the algorithm is concerned, a conspiracy theory about 9/11 being a controlled demolition is worth promoting because people are reading, sharing, and reacting to it with strong signals at high velocity. The platform promoted a fake Megyn Kelly story from a right-wing site because people were being told what they wanted to hear, which caused them to eagerly engage with that story.

The BuzzFeed News analysis of more than 1,000 posts from hyperpartisan Facebook pages found that false or misleading content that reinforces existing beliefs received stronger engagement than accurate, factual content. The internet and Facebook are increasingly awash in fake or deeply misleading news because it generates significant traffic and social engagement.

“We’re just beginning to understand the impact of socially and algorithmically curated news on human discourse, and we’re just beginning to untie all of that with filter bubbles and conspiracy theories,” Starbird said. “We’ve got these society-level problems and Facebook is in the center of it.”

This reality is at odds with Facebook’s vision of a network where people connect and share important information about themselves and the world around them. Facebook has an optimistic view that in aggregate people will find and share truth, but the data increasingly says the exact opposite is happening on a massive scale.

“You have a problem with people of my parents’ generation who … are overwhelmed with information that may or may not be true and they can’t tell the difference,” Starbird said. “And more and more that’s all of us.”

The fact that Facebook’s own Trending algorithm keeps promoting fake news is the strongest piece of evidence that this kind of content overperforms on Facebook. A reliable Trending algorithm would have to find a way to account for that in order to keep dubious content out of the review team's queue.

How to train your algorithm

In order for an algorithm to spot a valid trending topic, and to discard false or otherwise invalid ones, it must be trained. That means feeding it a constant stream of data and telling it how to interpret it. This is called machine learning. Its application to the world of news and social media discussion — and in particular to the accuracy of news or circulating rumors and content — is relatively new.

Algorithms are trained using past data. This past data helps train the machine on what to look for in the future. One inevitable weakness is that an algorithm cannot predict what every new rumor, hoax, news story, or topic will look like.

“If the current hoax is very similar to a previous hoax, I’m sure [an algorithm] can pick it up,” Bontcheva said. “But if it’s something quite different from what they’ve seen before, then that becomes a difficult thing to do.”

As a way to account for unforeseen data, and the bias of users, the Trending product previously relied heavily on dedicated human editors and on the news media. In considering a potential topic, Facebook’s editors were required to check “whether the topic is national or global breaking news that is being covered by most or all of ten major media outlets.” They were also previously tasked with writing descriptions for each topic. Those descriptions had to contain facts that were “corroborated by reporting from at least three of a list of more than a thousand media outlets,” according to a statement from Facebook. The review team guidelines do not include either process.

The algorithm also used to crawl a large list of RSS feeds of reputable media outlets in order to identify breaking news events for possible inclusion as a topic. A Facebook spokesperson told BuzzFeed News that the algorithm no longer crawls RSS feeds to look for possible topics.

Facebook says it continues to work to improve the algorithm, and part of that work involves applying some of the approaches it implemented in News Feed to reduce clickbait and hoaxes.

“We’ve actually spent a lot of time on News Feed to reduce [fake stories and hoaxes’] prevalence in the ecosystem,” said Adam Mosseri, the head of News Feed, at a recent TechCrunch event.

Bontcheva and others said Facebook must find ways to ensure that it only promotes topics and related articles that have a diverse set of people talking about them. The algorithm needs be able to identify “that this information is interesting and seems valid to a large group of diverse people,” said Starbird. It must avoid topics and stories that are only circulating among “a small group of people that are isolated.”

It’s not enough for a topic or story to be popular — the algorithm must understand who it’s trending among, and whether people from different friend networks are engaging with the topic and content.

“Surely Facebook knows which users are like each other,” Bontcheva said. “You could even imagine Facebook weighting some of these [topics and stories] based on a given user and how many of the comments come from people like like him or her.”

This means having a trending algorithm that can recognize and account for the very same ideological filter bubbles that currently drive so much engagement on Facebook.

The Trending algorithm does factor in whether a potential topic is being discussed among large numbers of people, and whether these people are sharing more than one link about the topic, according to a Facebook spokesperson.

A suboptimal solution?

Over time, this algorithm might learn whether certain users are prone to talking about and sharing information that’s only of interest to a small group of people who are just like them. The algorithm will also see which websites and news sources are producing content that doesn’t move between diverse networks of users. To keep improving, it will need to collect and store this data about people and websites, and it will assign “reliability” scores based on what it learns, according to Bontcheva.

“Implicitly, algorithms will have some kind of reliability score based on past data,” she said.

Yes, that means Facebook could in time rate the reliability and overall appeal of the information you engage with, as well as the reliability and appeal of stories from websites and other sources.

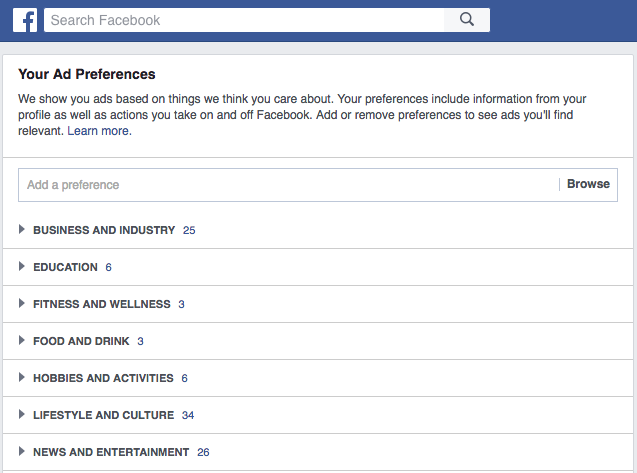

This would lead to all manner of questions: If Facebook deems you to be an unreliable source of trending topics and information, should it have to disclose that to you, just as it does your ad preferences? Should news websites be able to see how the algorithm views them at any given time?

Then there’s the fundamental question of whether suppression of information and sources by algorithm is preferable to suppression by humans.

“Previously the editors were accused of bias, but if [Facebook] starts building algorithms that are actually capable of removing those hoaxes altogether, isn’t the algorithm going to be accused of bias and propaganda and hidden agendas?” said Bontcheva.

A spokesperson for the company said the current Trending algorithm factors in how much people have been engaging with a news source when it chooses which topics and articles to highlight. But they emphasized that this form of rating is not permanent and only pays attention to recent weeks of engagement. They will not maintain a permanent black or white list of sources for Trending. The company also said that the top news story selected for a given topic is often the same story that's at the top of the Facebook search results for that topic or term, meaning it's selected by an algorithm.

Now consider what might happen if, for example, there's a discussion about vaccines happening on a large scale. Maybe the algorithm sees that it's generating enough engagement to be trending, and maybe the top story is from an anti-vaccine website or blog. The algorithm may put that topic and story in the queue for review. Would a reviewer promote the topic with that story? Would they recognize that the anti-vaccine argument stems from "demonstrably false information," as their guidelines prescribe, and suppress the topic and story? Or would they promote the topic but select a different story?

Those decisions are the kinds that editors make, but Trending doesn't have those anymore. Given recent failures, it's impossible to predict what might happen in this scenario.

“Is a suboptimal solution good enough, and what are the consequences of that?” Starbird asks. “And are we as a society OK with that?”