Some of the world’s biggest brands were ripped off by a digital fraud scheme that used a network of websites connected to US advertising industry insiders to steal what experts say could be millions of dollars, a BuzzFeed News investigation has found.

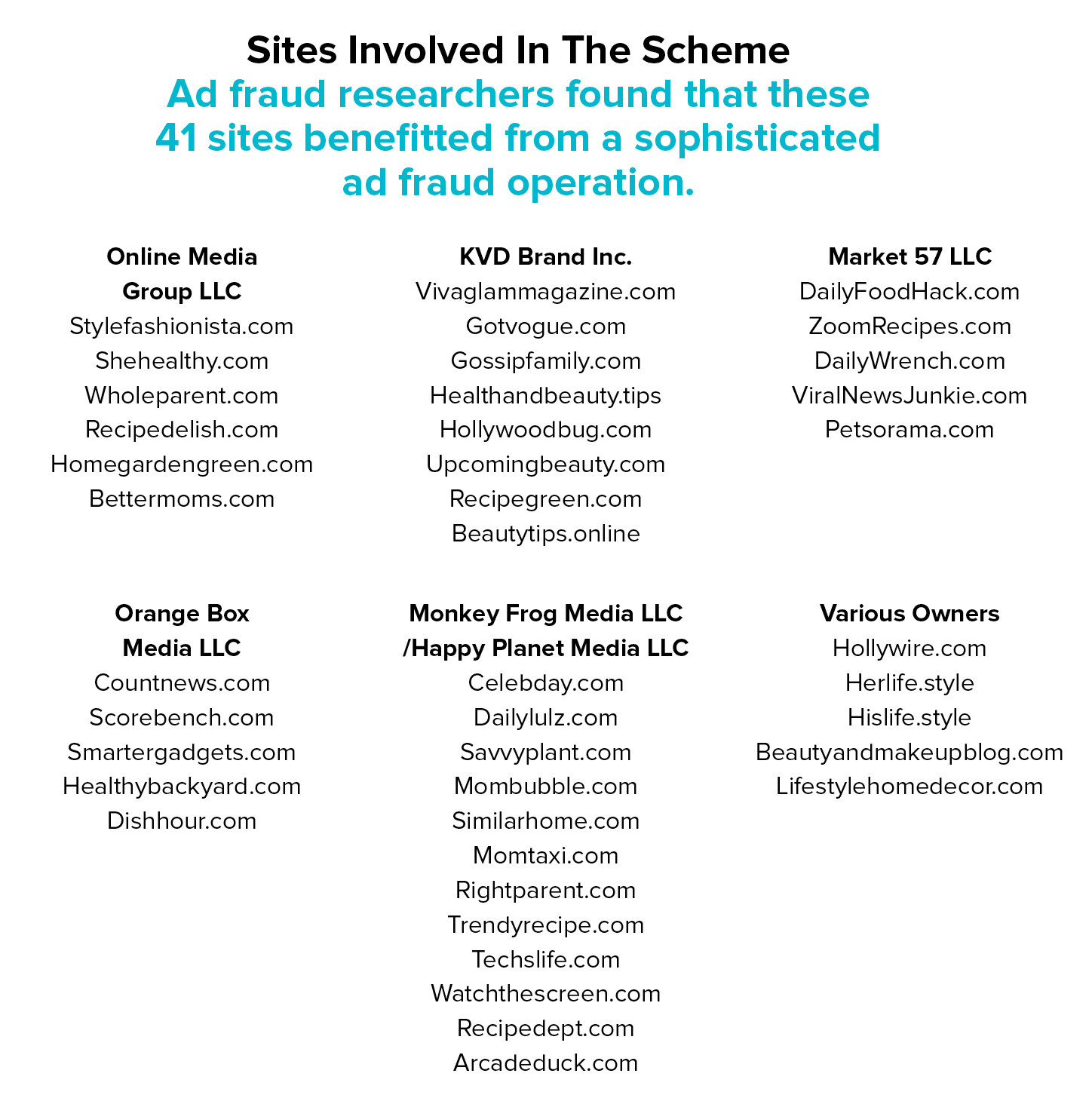

Approximately 40 websites used special code that triggered an avalanche of fraudulent views of video ads from companies such as P&G, Unilever, Hershey’s, Johnson & Johnson, Ford, and MGM, according to data gathered by ad fraud investigation firm Social Puncher in collaboration with BuzzFeed News. Over 100 brands saw their ads fraudulently displayed on the sites, and roughly 50 brands appeared multiple times.

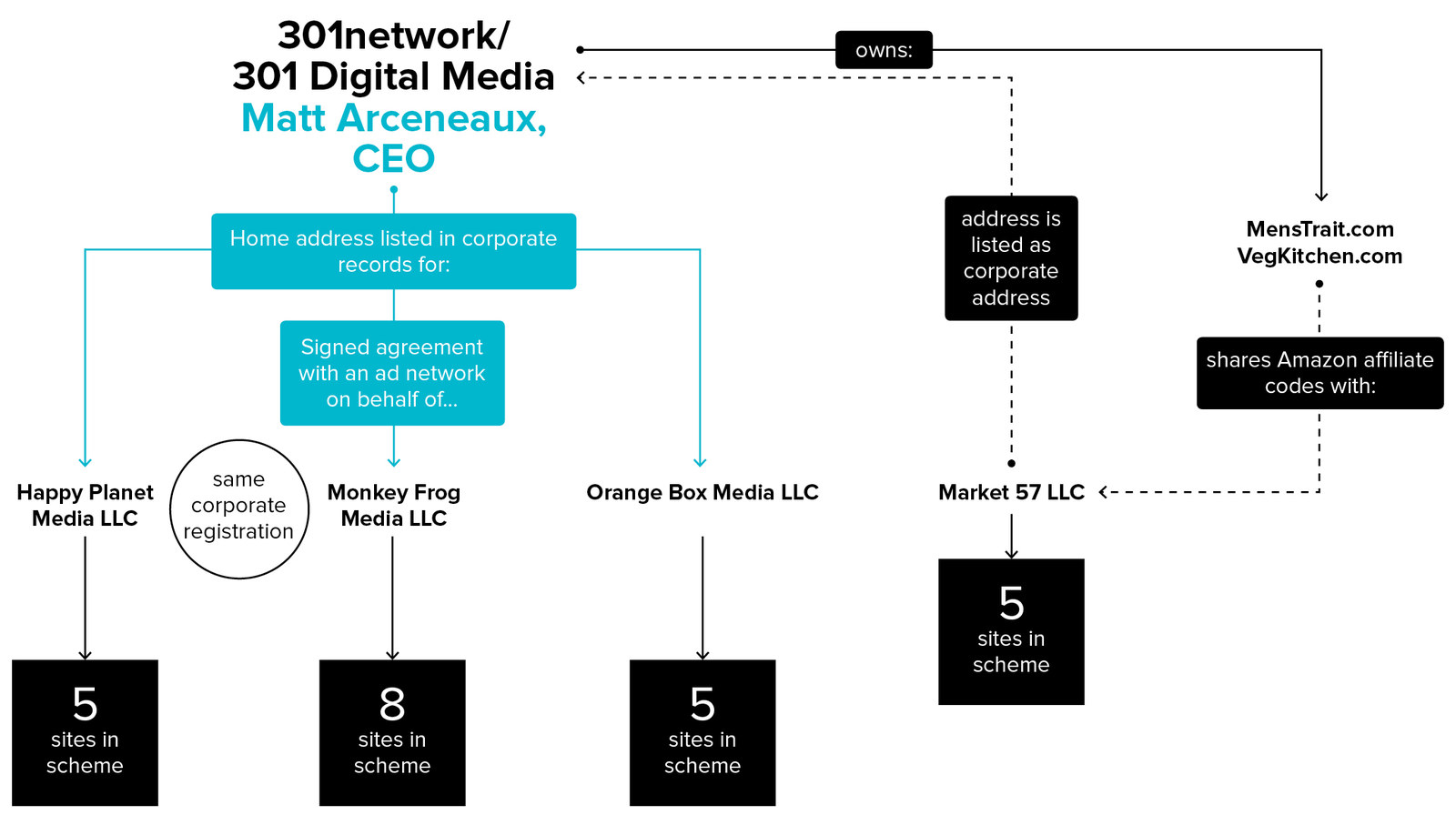

Documents obtained by BuzzFeed News reveal that the CEO of an ad platform and digital marketing agency is an owner of 12 websites that earned revenue from the fraudulent views, and his company provided the ad platform used by sites in the scheme. Another key player is a former employee of a large ad network who runs a group of eight sites that were part of the fraud, and who consults for a company with another eight sites in it. That company is owned by a model and online entrepreneur who played Bob Saget’s girlfriend on the HBO show Entourage. A final site researchers identified in the scheme is owned by the cofounder of one of the 20 largest ad networks in the United States.

In statements provided to BuzzFeed News by email, all parties deny any knowledge of fraudulent ad activity taking place on their websites. 301network, the ad platform used in the scheme, is now in the process of being shut down and many of the websites that participated have also been deactivated.

This scheme illustrates that while governments and platforms such as Facebook are grappling with online misinformation, the advertising world is in the midst of its own crisis brought on by a multibillion-dollar form of digital deception: ad fraud. This investigation also reveals how seemingly credible players in the ad supply chain can play an active role in — and profit from — fraud.

It's yet another example of how the digital ad industry is being rocked by concerns about quality, fraud, and brand safety. YouTube lost millions of dollars in advertising after it was revealed that ads from major brands were showing up next to extremist videos. P&G, one of the world's biggest advertisers, recently withheld more than $100 million of digital ad spend and found it had little impact on its business. "What that tells me is that the spending we cut was largely ineffective," said CEO David Taylor.

Social Puncher, which publishes ad fraud investigations at SadBotTrue.com, estimates this scheme could have stolen as much as $20 million this year. Pixalate, a fraud prevention and detection company, recently exposed a group of seven sites involved in the scheme as a result of its own independent investigation. It estimated that “a sustained attack [from just one website] could net the fraudsters over $2 million per year.”

Another fraud detection company, Integral Ad Science, reviewed sites that participated in the scheme and found they engaged in fraudulent tactics to generate ad impressions. “Those sites present various degrees of fraud, and they have been flagged accordingly to our customers,” Maria Pousa, the chief marketing officer of IAS, told BuzzFeed News.

“We have stopped the dumb criminals. Now we need to be able to stop the smart criminals.”

Kristin Lemkau, the chief marketing officer of JPMorgan Chase, recently said advertisers are expected to lose $16.4 billion this year to ad fraud, more than double what was stolen in 2016.

Mike Zaneis, CEO of Trustworthy Accountability Group, an anti-fraud initiative set up by the ad industry's key trade groups, told BuzzFeed News some in the industry enable fraud because they look the other way and let it happen, while others actively participate. “There are errors of omission and then there are errors of commission,” he said.

In spite of rising losses and brand concerns, Zaneis believes recent initiatives in the industry have made it more difficult for criminals to make money from ad fraud, which has in turn required them to develop more-sophisticated attacks.

“It was so easy to just turn on the nonhuman traffic and there was no accountability, and that’s no longer the case,” he said. “We have stopped the dumb criminals. Now we need to be able to stop the smart criminals.”

What caught the attention of researchers at Pixalate and Social Puncher, two companies that identified the fraud independently of each other, was that sites in the scheme deployed a sophisticated method to automatically redirect traffic between websites in order to rack up ad impressions and avoid detection. Once caught in this web of redirects, the sites show a constant stream of video ads that are often barely interrupted by actual editorial content. In some cases, the sites showed more than one video ad at the same time in order to increase revenue.

Jalal Nasir, the CEO of Pixalate, referred to the sites in the scheme as “self-driven” because once the redirect code is initiated it can bounce between websites without any action required on the part of a human user or bot. (This kind of attack is known as “session hijacking.”)

“The people profiting from this scheme could have initiated the first visit to the URL, simply to open as many windows or tabs as possible on browsers,” he told BuzzFeed News. “Once that first step had been taken, however, the browsers could have been left open to ‘browse’ all day, ‘mimicking a human.’”

The websites in the scheme focus on niche topics, such as beauty, celebrity news, food, and parenting, that are popular with major advertisers and that can attract high ad rates. They had names such as BeautyTips.online, RightParent.com, HealthyBackyard.com, MomTaxi.com, and GossipFamily.com. In many cases the sites are filled with images and content that has been plagiarized or loosely rewritten from other websites. Others are filled with posts that read like poor translations of actual English.

“Don’t assume rumored baby bump of Kylie Jenner anytime soon,” begins a recent article on StyleFashionista.com. The headline is similarly nonsensical: “Kylie Jenner’s Post Instagram Posts A Fascinating Selection Of Shirts.”

Many of the sites appear to have been hastily thrown together: Some, such as UpcomingBeauty.com, still contain the default settings of the design template, and have newsletter signup boxes that are not configured. Others, such as StyleFashionista.com, have been online for a year and a half and yet do not appear to have a single user comment. (The “Recent Comments” section on its homepage is empty.)

Pixalate referred to the group of properties it investigated as “zombie sites” because of how they generate ad views without human action, and because it’s unlikely they could attract interest from a real audience.

If any real visitors did happen upon these sites, the scheme was designed to avoid detection by ensuring that a normal user visiting the homepage or regular URL would not be exposed to the malicious behavior. The sites were configured with a “friend or foe” system that only triggered the redirects when a specific URL was accessed. Once triggered, the secret URL would engage what Social Puncher came to refer to as “ad hell” due to the constant display of video ads and very little actual editorial content.

Social Puncher identified the secret URLs and then accessed them in order to verify the fraudulent ad display. For example, this video shows ads from top brands being shown as a small group of sites redirect between each other with no action taken on the part of the user:

Pixalate’s researchers documented the same behavior, as did Protected Media, another fraud detection company that examined the sites at BuzzFeed News’ request.

Along with the secret URLs, the scheme attempted to avoid detection by using a network of different sites to ensure no single property generated enough revenue to risk catching the attention of fraud detection companies, or of the brands being defrauded. Many sites in the scheme would launch, instantly gain traffic and ads, and then see their audience disappear months later. It was the digital equivalent of skimming from a casino.

Using the list of sites that Social Puncher and Pixalate identified, BuzzFeed News began to investigate the companies and people behind them. That trail led to two major owners/operators of sites who turned out to be Americans with ties to the US digital ad industry.

All sites involved in the scheme used ad technology provided by 301network, which is a company connected to 301 Digital Media, a marketing agency based in Nashville. (Pixalate also saw 301’s ad code in the sites it examined.) A cached version of its company page on LinkedIn cited Scripps and Pfizer as clients, and the company is a gold-level sponsor of a digital marketing conference taking place in New York next month.

When first contacted by BuzzFeed News about the presence of its ad platform code across the sites identified in the scheme, 301 CEO Matt Arceneaux said the company was in the process of shutting down its ad platform, and that he was unaware of any fraud.

“We had a few publishers still using our [supply-side platform] and ad server products, but in light of recent clawbacks from advertisers and other SSPs related to Monkey Frog Media and a few other publishers in the network, we decided to accelerate the wind down process,” he said in an email.

“Clawbacks” are demands for refunds, which in this case were made after Pixalate publicly exposed the ad fraud executed by seven sites owned by a shell company called Monkey Frog Media LLC. (The sites were all taken offline shortly after Pixalate’s blog post was published.)

Arceneaux portrayed it as a case of his small ad platform being exploited by unscrupulous players like Monkey Frog. However, documents obtained by BuzzFeed News combine with corporate records and other information to show that Arceneaux is actually an owner of Monkey Frog Media. Tennessee corporate records show that Monkey Frog Media goes by another name, Happy Planet Media. That company had another five sites involved in the scheme, all of which have public domain-registration records that list 301 Digital Media, Arceneaux’s company, as their owner.

Tennessee corporate records also show that two other LLCs with websites in the scheme have connections to 301 and/or Arceneaux. Market 57 LLC, which had five sites, lists its corporate address as the headquarters of 301. One of Market 57’s properties, ViralNewsJunkie.com, also contains the same unique Amazon affiliate code in its source code as two websites owned by 301. (The use of the code means that any products sold via the website earn 301 a commission.)

Orange Box Media LLC, which owns another five sites, is also registered in Tennessee and lists Arceneaux’s home address in its corporate records. (That same address appeared in an early version of the registration for Monkey Frog Media/Happy Planet Media.)

A final sign that these companies share an owner is that on September 8 at roughly noon Eastern the websites belonging to all three companies were taken offline at the same time, according to data gathered by Social Puncher.

Arceneaux initially denied any connection between the shell companies and 301. “Neither 301 Digital Media, 301 Ads nor 301 Network have any ownership in any of the businesses you mention.” He did not reply when asked to clarify if he or his partner, COO Andrew Becks, have personal stakes in the companies. (Becks did not respond to the question.)

Documents show that Arceneaux has been operating the Monkey Frog Media sites since at least 2015. On December 11 of that year, an employee of an ad tech company sent an email to get Monkey Frog’s websites set up as a customer. Arceneaux was identified as the “manager” of Monkey Frog when he signed the contract, and was also listed as the company contact. BuzzFeed News obtained a copy of the email and contract with Arceneaux’s signature.

After being informed of the existence of a Monkey Frog contract with his signature, Arceneaux issued a statement to deny that any fraud took place.

“No one profited from an ad fraud scheme as there was no ad fraud scheme evidence shown in any data that we have collected or seen,” Arceneaux said. “We ran all publishers through 3rd party ad fraud detection companies and were not notified of any issues until shortly before they were removed from our platform. We always make sure any person or publisher running on our network is fully compliant with our 3rd party fraud detection partner.”

He argued that the behavior of the Monkey Frog sites was not suspicious:

“We take real ad fraud very seriously. After reviewing the behavior on the sites in question, we did not observe anything other than auto-advancing pages similar to what YouTube and Pandora do. We did not observe any attempts to mimic human behaviors or automatically click on ads. The 301network SSP has since notified all publishers that it is ceasing operations and can proudly say that none of the sites that showed this behavior are operational anymore.”

This is not the first time Arceneaux has run into problems with fraud on his sites. Shailin Dhar is today the founder of ad fraud research firm Method Media Intelligence, but back in 2015 he was working at an ad network when Arceneaux approached the company to get his Monkey Frog sites signed up. Dhar told BuzzFeed News that that same year he also looked into two 301 Digital Media properties, BridalTune.com and MensTrait.com. Dhar was told by AppNexus, a major ad platform, that its quality team removed the sites from the ad exchange “after they detected and confirmed significant amounts of nonhuman traffic coming through the sites.”

Dhar provided a copy of the email to BuzzFeed News and it can be viewed here.

“While managing supply quality for an ad network client, I regularly saw traffic quality flags with sites from 301 Digital and Monkey Frog,” Dhar told BuzzFeed News. “While these sites fit the mold for getting accepted into ad exchanges, they were repeatedly flagged by AppNexus and other SSPs we used. When I tried to get more insight as to why they were flagged, the platforms simply told us it was an open-and-shut case with nothing to debate over.”

“The content they put out was so light and it was such fluff and had so little value it was hard to believe they were getting so much traffic and revenue on it.”

An archived version of 301’s media kit from early 2015 claimed that the two sites later flagged by AppNexus combined with five others to attract roughly 9 million unique visitors per month. These were the marquee 301 publishing properties at the time. But today, almost all of those sites are inactive or completely dead.

BuzzFeed News spoke to three people who previously wrote content for different 301 websites. When one was told that 301 was linked to an ad fraud scheme, they said, “it’s not surprising at all.”

“The content they put out was so light and it was such fluff and had so little value it was hard to believe they were getting so much traffic and revenue on it,” they said. (They asked to not be identified in order to avoid being publicly linked to 301.)

BuzzFeed News’ investigation into sites in the scheme also led to another man with a connection to the US ad industry.

A shell company with the name Online Media Group LLC owns seven sites that ran the session hijacking code. Many of the sites appear to have no user comments on their content, and the articles are written in a malformed version of English that suggests they were automatically generated, or produced by a writer with low proficiency in the language. The sites do not have social media accounts to help attract an audience.

The vice president of OMG LLC is a man named Eric Willis. He told BuzzFeed News he has “no knowledge of any fraudulent activity.”

“The industry as a whole definitely has a big problem with fraud and we do everything possible to prevent this kind of activity,” he said. Willis did not reply to a detailed series of questions from BuzzFeed News. In addition to listing his current job with OMG LLC, his LinkedIn profile says he previously worked for a large US ad network called AdSupply.

“The industry as a whole definitely has a big problem with fraud.”

None of the websites identified by Social Puncher or Pixalate are part of the AdSupply ad network. BuzzFeed News did, however, find that the company’s cofounder and executive vice president, Chris Corson, is part owner of an LLC that operates Hollywire.com, a site that contained the session hijacking code. Unlike nearly all the other sites identified in the scheme, Hollywire is a longstanding web property that produces some original content, and has a YouTube channel with close to 2 million subscribers.

Along with being linked to Corson via corporate records, the address Hollywire.com lists in its domain registration records is the same as the AdSupply office in Los Angeles, and the email registered for the domain is domains@adsupply.com.

Corson said in an email to BuzzFeed News that he “had no involvement with Hollywire for at least 6 years, and was likewise never involved in Hollywire’s day-to-day activities or advertising activity.”

“I do not support or have any involvement in any type of fraudulent activities, and certainly not this ‘scheme’ you have identified from the [Pixalate] article, and to report anything to the contrary would be wildly reckless,” he said.

Corson is the part owner of another LLC, called Focus Marketing. Its website and the website for OMG LLC, the company Willis works for, are exact copies. It appears that OMG LLC cloned the Focus website and filled in its company name. It even lists the same two products in the case studies section of the website. One of those is a weight-loss product called AllDaySlim. It’s owned by a company called Lepton Labs LLC, which is also owned by Corson.

“To be clear, I do not have any involvement in the operations of Online Media Group or in any of its advertising activities,” Corson told BuzzFeed News. He declined to comment on OMG’s use of the Focus Marketing website design and content. He also did not provide the name or contact information of the person in charge of Hollywire. An email sent via the site’s contact form went unanswered.

Researchers at Pixalate found another connection between OMG LLC and Hollywire: Some of the traffic being routed through OnlineMediaGroupLLC.com was directed to Hollywire, according to the researchers. Pixalate told BuzzFeed News it considered this and other traffic going to Hollywire to be suspicious.

“Upon a more granular analysis, we noted that the incoming traffic to OnlineMediaGroupLLC.com ends up being directed to the same sites on the way out, indicating a suspicious family of sites,” according to an analysis Pixalate provided to BuzzFeed News.

It’s not just OnlineMediaGroupLLC.com that routed traffic to Hollywire. Social Puncher documented a loop of redirects that saw Hollywire pass traffic back and forth between HisLife.style and HerLife.style, two sites that historical domain records from DomainTools show were registered by Willis in late 2015.

Along with being the vice president of OMG LLC, Willis works with another company, KVD Brand Inc. It owns eight sites in the session hijacking scheme. KVD is run by Los Angeles model and online publisher Katarina Van Derham, who achieved fame by playing Bob Saget’s girlfriend on the HBO show Entourage.

“I am in complete shock,” Van Derham told BuzzFeed News in an email after being informed that some of her sites were part of an ad fraud scheme, and that they contained plagiarized content.

Van Derham subsequently said she purchased several of the sites from someone in Pakistan, and that after being alerted to the fraud issue by BuzzFeed News she discovered that “malware” was present on them.

“We have since then been doing our best to better properly secure the sites from further hacking or malicious attacks,” she said, adding that the plagiarized content was for the most part published before she took over the sites. “We definitely take responsibility for not paying closer attention to what the writers were doing or auditing the sites sufficiently for malicious code.”

However, by cross-referencing domain ownership records from DomainTools with Alexa traffic-ranking patterns, and the dates on articles on her websites, BuzzFeed News was able to establish that the suspicious traffic patterns and at least some plagiarism occurred after her acquisitions. Van Derham also acknowledged in an earlier email that she works with 301, meaning that her company, not the previous owners, has a relationship with the ad platform that is a common thread in the scheme.

Another piece of information that calls her claim of third-party malware into question is that Social Puncher detected session hijacking on VivaGlamMagazine.com. Van Derham has operated the Viva Glam site since 2012, and it was not purchased from Pakistan or elsewhere. It’s her marquee property and uses writers to produce real content.

Van Derham said she has no knowledge of any ad fraud.

“They flip the switch and the traffic, the spigot, just turns on.”

“You keep stating that fraud took place on the site but I still have no knowledge of anything fraudulent taking place,” she said in an email. “My company is still very small and doesn’t make enough to even cover the overhead.”

She added, “Like any new business of course we have our growing pains just as I know Buzzfeed went through its own period being accused of click bait in its early years but our goal is to grow and provide quality resources and information for our growing audience of women.”

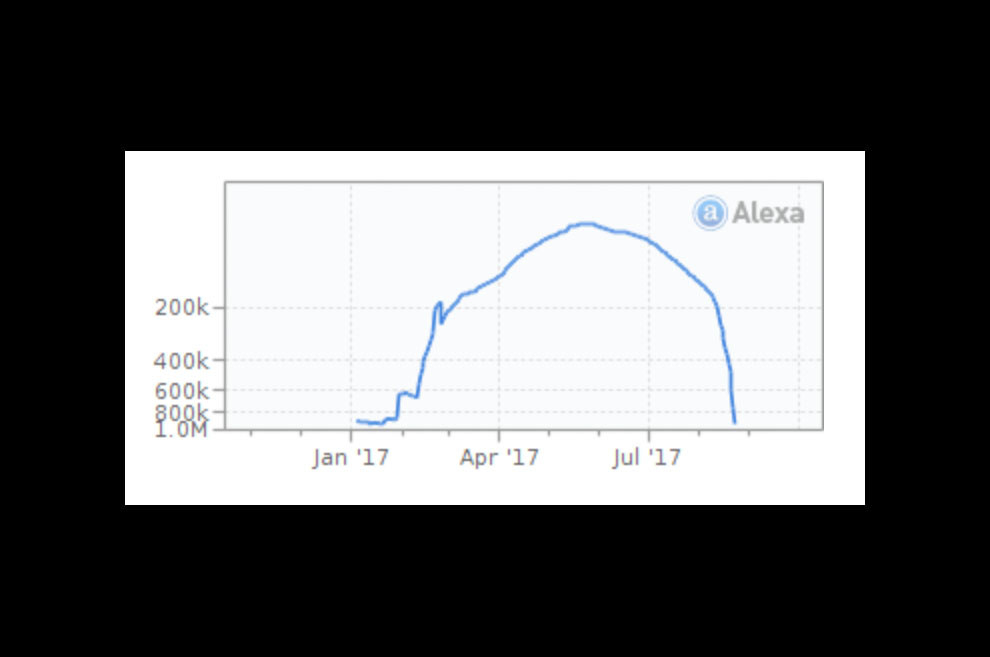

The audience behavior on several of Van Derham’s sites provides a good case study of the scheme. Last December, she purchased RecipeGreen.com for $59 in an online auction. From January until the end of August it was showered with traffic. Then the visits suddenly stopped, as shown by this Alexa traffic ranking chart:

The chart shows that in January RecipeGreen.com was barely in the top 1 million sites ranked by Alexa. By March it had almost cracked the top 200,000 and by June it was on its way to the top 100,000.

“They flip the switch and the traffic, the spigot, just turns on,” said Zaneis of TAG, the ad industry’s anti-fraud initiative.

By September RecipeGreen.com’s traffic had evaporated and the site was back clinging to top 1 million status, getting little traffic. The switch had been turned off.

Along with the traffic pattern, another suspicious signal is that the site kept the same content on its homepage, and did not upload new posts at any point since it was purchased. A screenshot included with the site’s for-sale listing on Flippa from close to a year ago shows the exact same articles in the exact same order that can be found at the top of the site’s homepage to this day:

KVD didn’t add new content or rotate the homepage, in spite of the fact that RecipeGreen.com is equipped with a plugin that enables it to be automatically updated with new recipe videos uploaded to YouTube. It did not need writers to actually produce content.

“100% Fully Automated Videos – You won’t have to worry about new content. Comes with a custom plugin with your own license,” read the sales pitch on Flippa.

Yet Van Derham told BuzzFeed News that, due to a lack of resources, the site was not updated. She attributed its impressive traffic growth to “a marketing campaign on advertise.com” that promoted the site’s content.

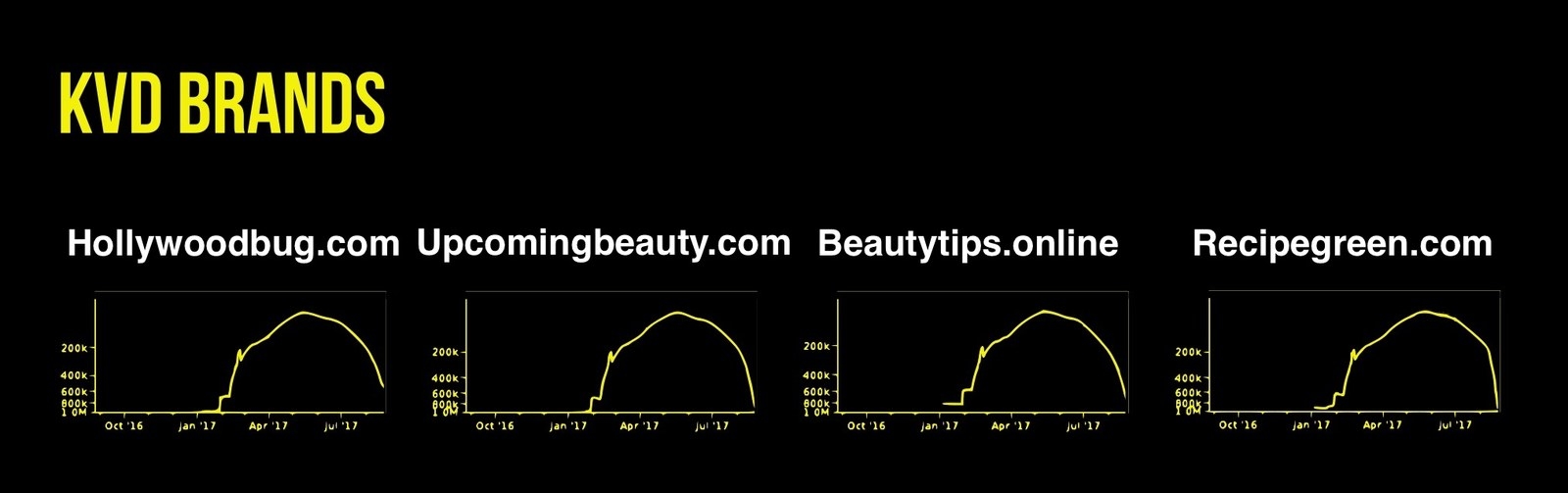

Another red flag for Recipe Green is that its exact Alexa traffic ranking pattern can also be found on three other KVD Brand websites:

This means the exact same users were visiting this group of websites at the same time over the span of roughly six months. Actual humans don’t behave like that — but bots that are part of a session hijacking attack, for example, could.

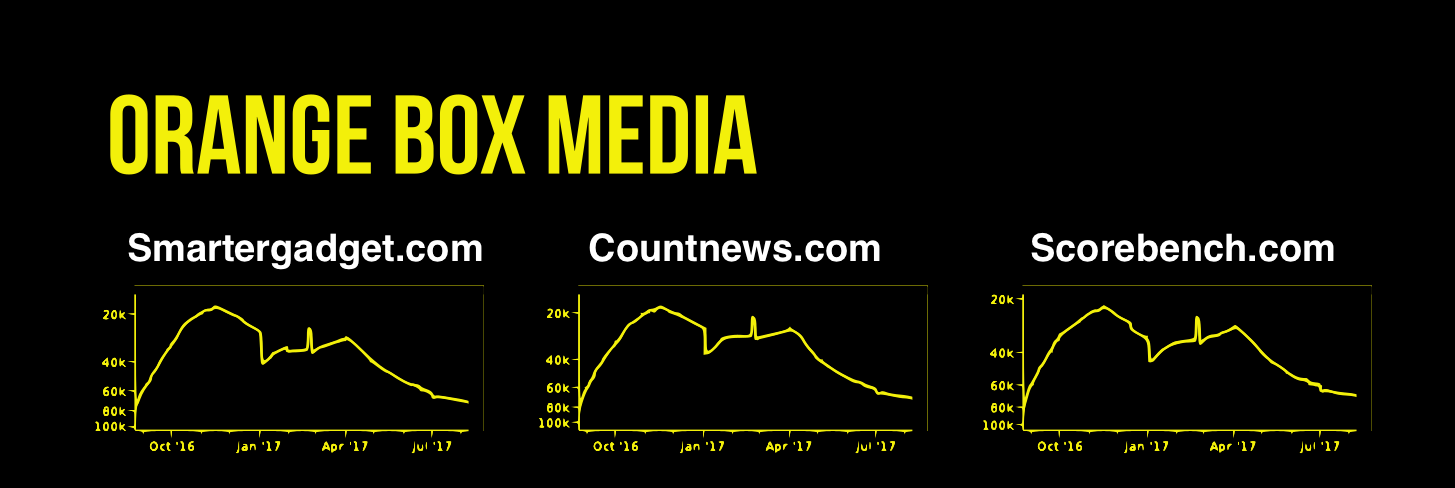

Almost all of the sites identified in the investigation have sister sites that share their exact same traffic rank pattern. Here are the Alexa traffic rank charts for three different Orange Box Media sites:

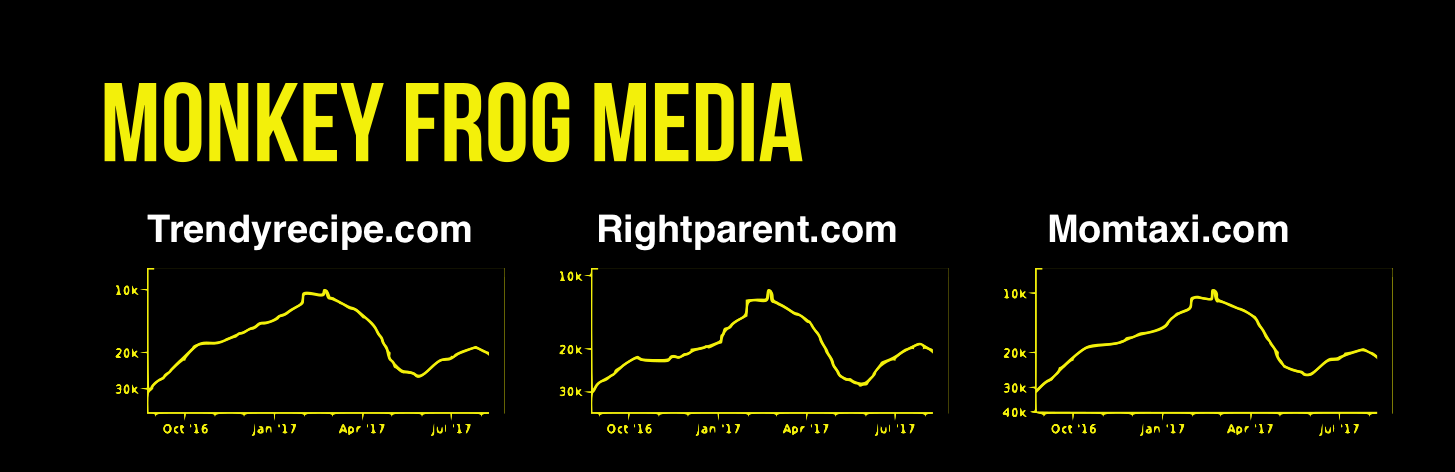

And three from Monkey Frog Media:

Amin Bandeali, the CTO of Pixalate, said his company constantly comes across websites like the ones involved in this scheme. “The scale is huge,” he said, noting that it takes no time to create a new website and fill it with plagiarized or sloppily aggregated content.

“People have actually built programs called website generators where with one [computer command] they can generate a whole website, including plagiarized content from other websites,” he said.

Zaneis of TAG said that stealing content is often the first step in setting up websites for ad fraud.

“These websites which you’ve identified, that's the piggybank, that’s the criminal’s ATM machine, that’s how they take money out of the supply chain. But in order to get there, there’s this whole chain of criminal activity, and it starts with the ad-supported piracy,” he said.

“There use to be a kind of way of thinking, ‘Oh, ad fraud is just the cost of doing business in the digital ad ecosystem.’ That’s bullshit.”

Zaneis said the permissive attitude toward fraud is coming to an end in the industry.

“There use to be a kind of way of thinking, ‘Oh, ad fraud is just the cost of doing business in the digital ad ecosystem.’ That’s bullshit,” he said. “Marketers didn’t plan to lose billions of dollars. That was an excuse a lot of people used when everyone was making money and the industry was growing by 20% [a year] and everything was good. But you can only operate with that kind of mentality for so long until accountability takes hold.”

One of the leading voices calling for accountability is Marc Pritchard, chief brand officer for consumer products giant P&G. A month ago, he took the stage at a major digital marketing conference and said P&G is working on multiple fronts to fight “criminal activity in digital advertising.” He said the company now ensures its ads only appear on digital properties belonging to a group of what he called “200 trusted media partners that have proven they’re clean.”

But that apparently isn’t the case: BuzzFeed News provided P&G with examples of fraudulent ads for 13 brands such as Secret, Orgullosa, Charmin, Olay, and Oral-B appearing on sites involved in the scheme.

View this video on YouTube

Social Puncher's video collection of top brands being fraudulently displayed on sites in the scheme.

As Pritchard strode the stage in Berlin to warn of the “murky, nontransparent, even fraudulent digital media supply chain,” many of the sites that had stolen ad dollars from him and other major brands continued to rack up fraudulent video ad impressions.

P&G declined to comment for this story. In a statement, MGM Resorts International said it suffered “very minimal exposure” and quickly blocked the sites from its ad buys.

“Our brand-safety protocols quickly detected the abnormal bot behavior, automatically shutting off ad placements to the affected sites and limiting our exposure to minimal levels,” said Mary Hynes, MGM’s director of corporate communication. “The platform at issue has been fully blocked from all our media programs.”

Unilever did not comment on how much money it lost to the scheme. It said in a statement that, “Our brands and media agency partners use a combination of cutting-edge technology and human checks as we strive to ensure our content is delivered in legitimate and credible environments.”

BuzzFeed News provided evidence to Johnson & Johnson, Hershey’s, Disney, and Ford of their ads appearing on the sites. All declined to comment.

“The main problem about ad fraud is that brands, which lose shareholders’ money, do not want to speak about it," said Vlad Shevtsov, the director of investigations for Social Puncher. "Even in obvious cases like this one.” ●