Robyn Byrd thought her plan was working when the letter from her hero arrived in the mail. It was 1994, and the 13-year-old had sent the creator of The Ren & Stimpy Show a video of herself talking about her drawings and the animation career she envisioned; she thought if she got the attention of the studio behind the hit Nickelodeon show, she might get a job there someday. John Kricfalusi’s effusive letter, Byrd said, seemed like the first step toward her dream.

She could hardly believe he’d responded. “I had built up these characters and this mythos of Ren & Stimpy in my head,” Byrd, now 37, told BuzzFeed News. “It was exciting.”

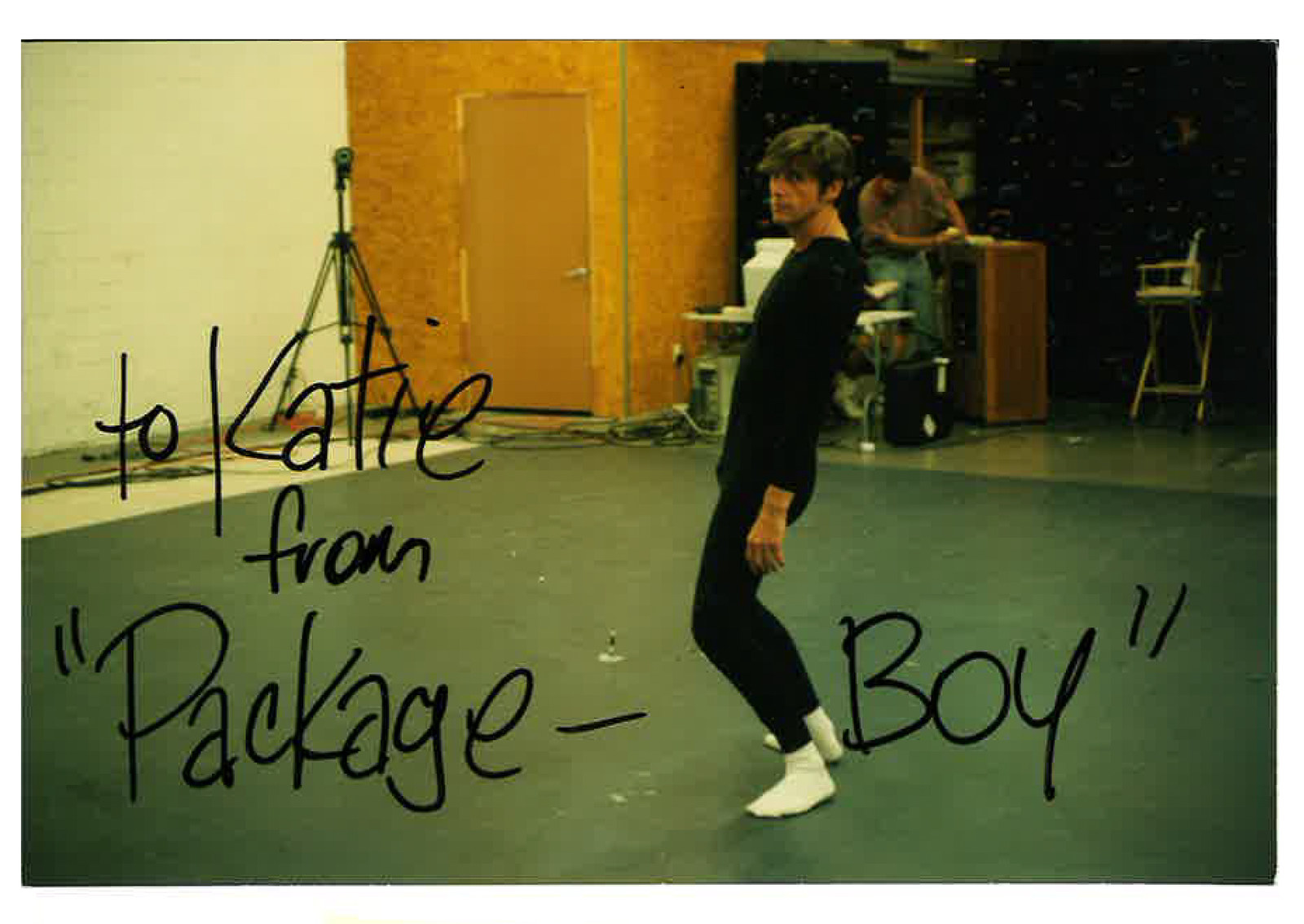

Soon, she said, she began receiving boxes of toys and art supplies from 39-year-old Kricfalusi, better known as John K. He helped her get her first AOL account, through which he convinced her he could help her become a great artist. He visited her at the trailer park where she lived in Tucson, Arizona. “I thought I was still his little cute friend,” she said. And then, when she was still in 11th grade, he flew her to Los Angeles to show her his studio and talk about her future. She said that on the same trip, in a room with a sliding glass door that led to his pool, he touched her genitals through her pajamas as she lay frozen on a blanket he’d placed on the floor. She was 16.

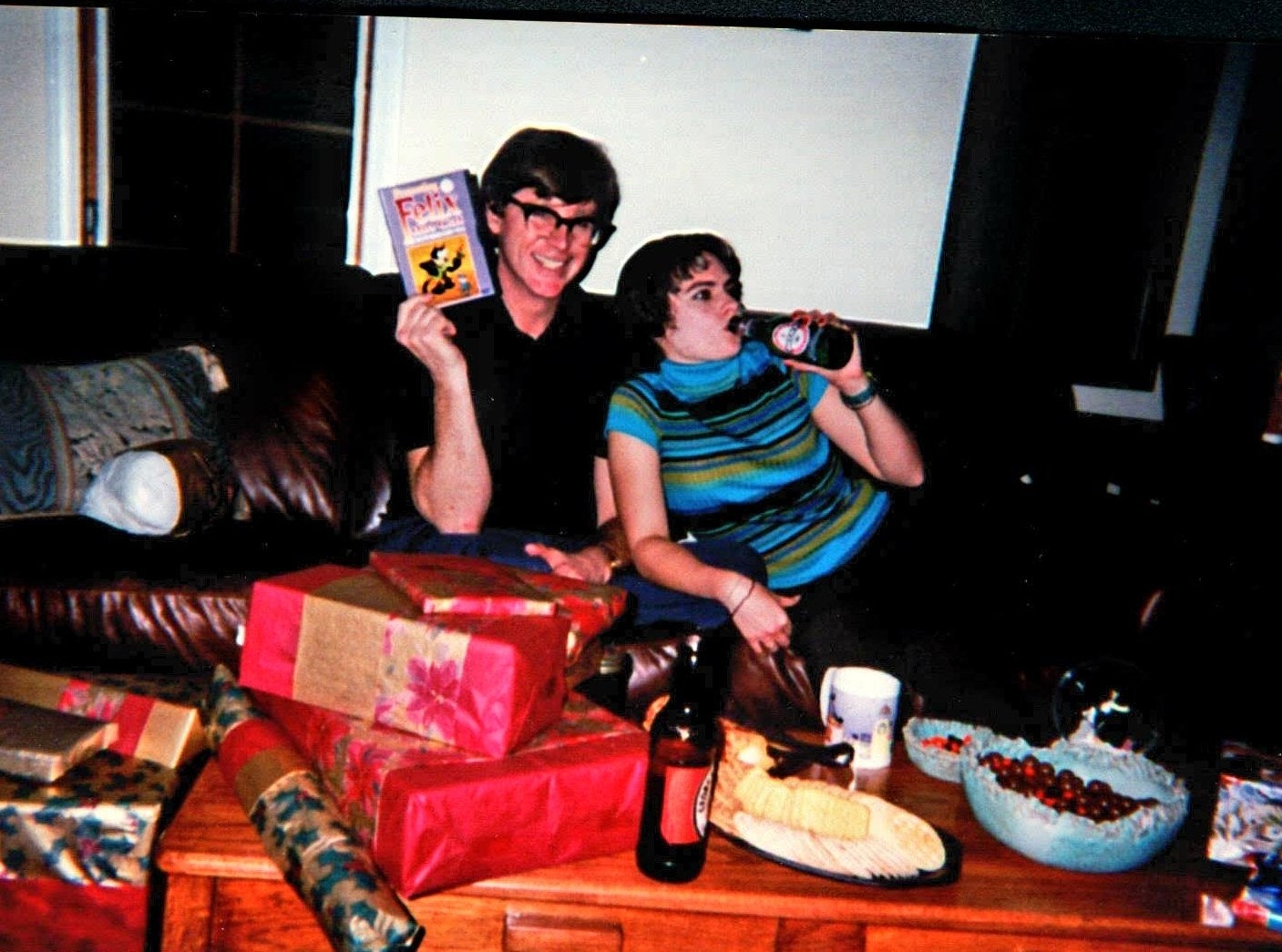

In the summer of 1997, before her senior year of high school, he flew her to Los Angeles again, where Byrd had an internship at Spumco, Kricfalusi’s studio, and lived with him as his 16-year-old girlfriend and intern. After finishing her senior year in Tucson, the tiny, dark-haired girl moved in with Kricfalusi permanently at age 17. She told herself that Kricfalusi was helping to launch her career; in the end, she fled animation to get away from him.

Since October, a national reckoning with sexual assault and harassment has not only felled dozens of prominent men, but also caused allegations made in the past to resurface. In some ways, the old transgressions are the most uncomfortable: They implicate not just the alleged abusers, but everyone who knew about the stories and chose to overlook them.

Although sexual abuse allegations against Kricfalusi have never been made public before, his relationship with Byrd has been an open secret within animation — so open that “a girl he had been dating since she was fifteen years old” was referenced briefly in a book about the history of Ren & Stimpy. Tony Mora, an art director at Warner Bros., and Gabe Swarr, a producer at Warner Bros., worked alongside Byrd at Spumco. The male artists said stories of how Kricfalusi sexually harassed female artists, including teenage girls, were known through the industry. “It’s always been there,” Mora said. Moreover, Kricfalusi made his fixation on teenage girls plainly obvious in his art, even as he worked on animated projects for the likes of Cartoon Network, Fox Kids, and Adult Swim. In an interview with Howard Stern in the mid-’90s, the radio host asked him about a character in the comic book anthology the cartoonist was then promoting. Stern called Sody Pop “a hot chick with big cans and nice legs.” Kricfalusi responded with a smile: “She’s underage, too.”

And yet Kricfalusi, 62, continues to be widely celebrated as a pioneer in the male-dominated field of animation. Creators of shows including SpongeBob SquarePants, Adventure Time, and Rick and Morty have cited Ren & Stimpy as an influence. After Nickelodeon fired the perpetually behind-schedule artist from Ren & Stimpy in 1992, he became an early proponent of art and shows made just for the internet. His output has slowed down, but he enjoys a living-legend stature that prompted 3,562 people to fund a Kickstarter campaign for his short Cans Without Labels, which he screened at a prestigious animation film festival in 2016. He made art for Miley Cyrus’s 2014 Bangerz tour; he animated two credit sequences on The Simpsons, the most recent in 2015. Until the publication of this story, his portrait hung on the wall at Nickelodeon.

On Kricfalusi’s behalf, an attorney responded to a detailed list of allegations in this story with the following statement:

“The 1990s were a time of mental and emotional fragility for Mr. Kricfalusi, especially after losing Ren and Stimpy, his most prized creation. For a brief time, 25 years ago, he had a 16-year-old girlfriend. Over the years John struggled with what were eventually diagnosed mental illnesses in 2008. To that point, for nearly three decades he had relied primarily on alcohol to self-medicate. Since that time he has worked feverishly on his mental health issues, and has been successful in stabilizing his life over the last decade. This achievement has allowed John the opportunity to grow and mature in ways he’d never had a chance at before.”

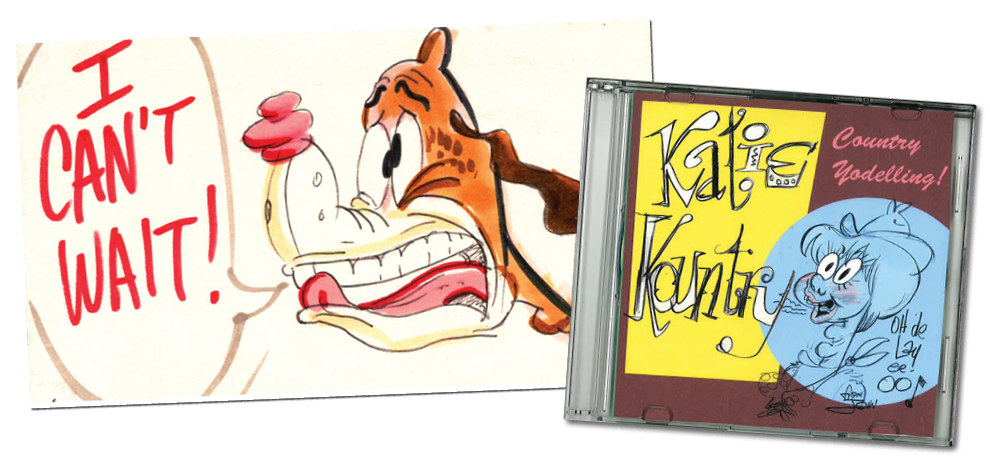

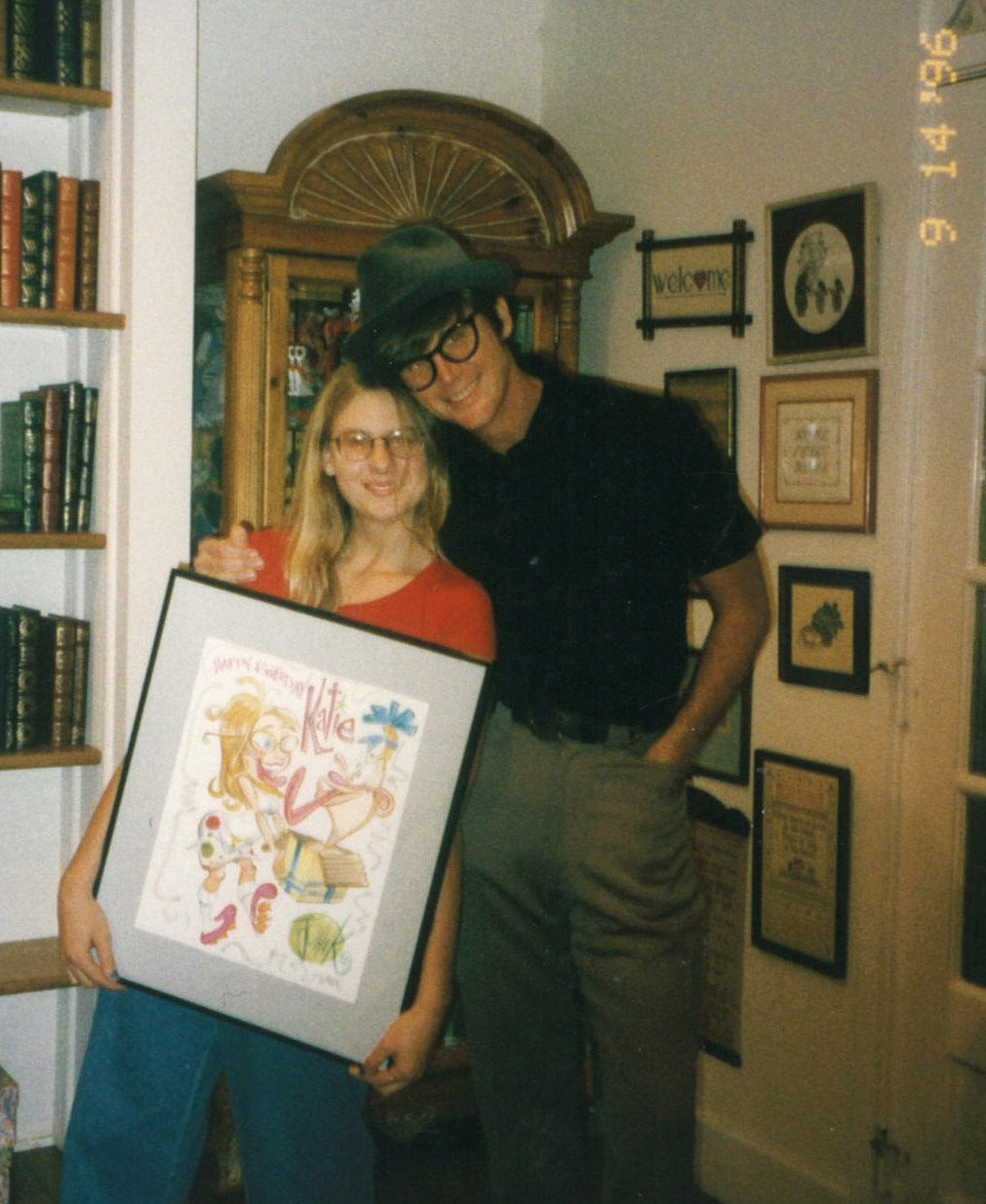

While Byrd felt deeply alone when she left animation, she later realized she hadn’t been the only underage girl Kricfalusi groomed for a relationship. In 2008, long after she last saw Kricfalusi, Byrd reconnected with an old internet friend: the artist Katie Rice. Kricfalusi introduced them through AOL in the mid-’90s, when they were still children, telling them he’d hire them both at Spumco someday. Although Kricfalusi never had a physical sexual relationship with Rice, he began hitting on her when she was a minor, she said, behavior that ranged from writing her flirty letters (“I bet you’ll be up to no good. Just like me,” he wrote in 1996) to masturbating while she was on the phone. In 2000, when Rice was 18 and trying to break into animation, Kricfalusi offered her a job. Once she started working for him, Rice said, he persistently sexually harassed her.

“I know a lot of people struggle with the ‘art vs. artist’ thing.”

Old letters, emails, and transcripts of AOL conversations between the women and Kricfalusi back up many of their claims. They each have witnesses to parts of their stories. Yet both women worried that they sounded “crazy.” For years, they chose to keep their experiences private, because coming forward didn’t seem like it was worth the risk. Rice feared retribution from his many supporters. Neither woman thought they’d be taken seriously.

Now they believe the world has changed. Byrd feels the time has come for Kricfalusi to be held accountable, particularly, she said, after the police told her in December that Kricfalusi’s alleged crimes against her were too old to investigate. “He shouldn’t be able to get away with that,” she said.

And while Byrd teaches philosophy and undergraduate writing classes, Rice still works in animation and regularly encounters people asking her what it was like to work for “a legend.” It made her hesitant to criticize him, as if it would be her fault for tainting his work. But, sitting in a Burbank restaurant, she said, “I know a lot of people struggle with the ‘art vs. artist’ thing, and I get it. Like, I love Rosemary’s Baby. But would I watch another movie that he made, knowing what I know now?” she said, referring to the multiple rape allegations against filmmaker Roman Polanski.

“I would say no, I don’t want to watch it. I don’t want any part of that. There’s nice people you can hire. There’s nice people who can make things, there’s nice people who make cartoons. … They’re just as fucking good.”

Rice wanted to be an artist from the time she was in the fourth grade. In the summer before fifth grade, when she started watching the original Nicktoons — Doug, Rugrats, and Ren & Stimpy — the tween decided to become a cartoonist. Her parents were skeptical. Her mother told BuzzFeed News that she worried her daughter was being unrealistic.

So when Rice wrote to Kricfalusi when she was around 14, and then they began corresponding over AOL, Rice said it was a source of validation for her and her family: A powerful man who had recently been nominated for an Emmy Award saw that she had potential.

They continued chatting online and on the phone into her sophomore year of high school, and Kricfalusi’s messages made her feel special. In an AOL conversation he told her not to copy and send to her friends, he said, “I wnat [sic] to squeeze you,” and “I’m crazy about you, Katie”; he asked her, “Do I ever make you tingle?” In an email she printed and saved from a few days after she turned 15, the 41-year-old man wrote, “I’m thinking about you very hard right now. And I have a little tickle in my chest.” Now 36, Rice looks at these old pages with some of the compliments underlined in purple gel pen and cringes.

“I think this 40 year old man is hitting on me,” Rice wrote in her diary. “But he’s never perverted. He is also very nice. He gives me a lot of drawing tips.”

At the time, she didn’t see the harm. “I think this 40 year old man is hitting on me,” she wrote in a diary entry from between December 1995 and March 1996, saying her friend agreed with her. (Speaking to BuzzFeed News, the friend recalled having this conversation, and that she thought Kricfalusi was hitting on Rice.) Rice, then 14, continued in her diary, “But he’s never perverted. He is also very nice. He gives me a lot of drawing tips.”

Rice and Kricfalusi met a few times in Los Angeles, and they kept talking after she moved with her parents from California to Lake Tahoe in 1996 when she was entering 10th grade at age 14. They never had physical sexual contact, but when Rice lived in Nevada, she remembers several late-night phone calls during which Kricfalusi said, “Repeat after me: John’s dick slides in my puzzy” (his pronunciation of the word) while he masturbated on the other end of the line. She refused. Rice, who was naive about sex, said she didn’t realize what he was doing at first — until, all of a sudden, she did. Christine Nockels, a high school friend of Rice who later worked at Spumco, said Rice told her about the masturbation when they were classmates.

The conversations left Rice shaken, but she trusted him. Lonely in her new school in Nevada, she viewed him as her only friend. He attended her 15th birthday party, which he later confirmed on a DVD extra for the 2003 Ren & Stimpy reboot. (“I was at her 15th birthday party. We’ll tell you that backstory a little bit later,” he said with a grin.) She was devastated when he abruptly stopped talking to her in early 1997.

That same winter, Kricfalusi flew out to visit Byrd, then a high school junior, at home in Arizona. They had sex for the first time at a nearby hotel, she said, and put into motion a series of decisions that would reshape the rest of her teenage years. She’d move in with Kricfalusi for the summer and intern at Spumco, then complete her senior year at a private school in Arizona, and he would cover the tuition. He told her he could give her an animation career in Los Angeles when she graduated. She and her mother believed him.

So when the young artist and writer moved in with Kricfalusi in the summer of 1997, part of her was happy. As an intern, she was making copies, keeping art organized, and learning how to be an animator. “I made my dream come true,” Byrd said. “That’s why I sent the tape when I was 13.” Everything in California was new and exciting, including, to some degree, her boyfriend. “I believed, as a 16-year-old dating him, ‘Oh, the world’s against us. It shouldn’t be wrong for him to date me. We’re cool and rebellious because we’re breaking the rules of society,’” Byrd told BuzzFeed News. She said he told her their 25-year age difference was “romantic.”

But she struggled. In a letter she wrote to herself during the internship — her method of working out her feelings at the time — she frets about all the ways she’s alienating her 41-year-old boyfriend with her “nagging” and her “guilt-inflicting”; she says Kricfalusi doesn’t care about her emotional well-being. “He may like my figure & face. He may adore my mind & ideas. But he does not have regard for my feelings as I do his,” she wrote. The artist she shared an office with, Swarr, who was in his early twenties at the time, remembers her frequently crying.

“I was like, ‘Who’s that little girl?’”

Despite the volatility, this seemed like a break to her: Kricfalusi was teaching her a trade. And, over the course of more than 600 blog posts reviewed by BuzzFeed News, Kricfalusi portrays himself as a uniquely qualified molder of young minds. It’s the same image he presented to Byrd and Rice, and to many of the fans, mostly men in their twenties, who he hired at Spumco in the 1990s and early 2000s. They were inexperienced young people who, Mora and Swarr said, believed deeply in the art Spumco was making. It was a small studio that usually had between 10 and 30 artists at a time, most of them convinced they were doing something defiant by working there. Derrick J. Wyatt, an artist who started working at Spumco in 1999, told BuzzFeed News the studio was a “cult of personality” centered on Kricfalusi.

After Byrd graduated from high school at 17 in 1998, Kricfalusi hired her to work at Spumco and she moved back into his Los Angeles home.

As Byrd grew up in the studio, her coworkers, many of whom were not much older than she was, were aware of the teen’s romantic relationship with their boss. Mora got an internship at Spumco in 1997, around the age of 24, and when he first started seeing Byrd around the studio, “I was like, ‘Who’s that little girl?’” he said. The relationship was odd to him, but it seemed to be accepted at the studio, where former employees say Kricfalusi fostered a libertine atmosphere in which taking offense was itself offensive. They were making shows with sexual themes; there were raunchy nude drawings on display. Mora said Kricfalusi left out a drawing he made of Byrd, naked, with a dog ejaculating on her.

Sometime between 1998 and 2000, Mora went to a party at Kricfalusi’s house that has bothered him for years. He remembered Byrd, who was no older than 20, was drunk and seemed to be drifting in and out of consciousness when Kricfalusi called Mora over to him. “And then he pulled out these Polaroids of Robyn basically — how can you say it? — going down on him. … He’s like, ‘What do you think of that?’”

“My entire life had been suspended in John's since I was fourteen.”

Byrd doesn’t remember Kricfalusi taking explicit photos of her; she also wasn’t aware, she said, that he showed explicit photos of her to other people. But Wyatt recounted an interaction with his then-boss that was similar to Mora’s. He said that at a party at Kricfalusi’s house between 1999 and 2002, Kricfalusi showed him “a stack of Polaroids” of Kricfalusi and Byrd having sex. He never mentioned the photographs to Byrd, nor did he confront Kricfalusi about the interaction. During another party at Kricfalusi’s house, Swarr said the artist pulled out a binder of photos that showed Byrd naked in his pool. “It was gross,” Swarr said. Affecting a gruff voice when he spoke as Kricfalusi, Swarr recalled, “He was like, ‘Oh, you like that?’ I was like, ‘No!’”

At the time Byrd started working at Spumco, the age of consent in California had been 18 for decades. But because no one in the studio told her to leave Kricfalusi, it took longer for Byrd to realize the extent of the problem she had. “My entire life had been suspended in John's since I was fourteen,” she wrote to Rice in 2008. She told BuzzFeed News this year, “I just kind of got swept up in the whole thing.” When it came to sex with an adult man, she remembers thinking as a teen that it was something “I was supposed to do as an adult woman.”

In 2000, Byrd briefly broke up with Kricfalusi and moved out of the house she shared with him in LA. The pair would reunite a few months later, but in the meantime, Kricfalusi contacted Rice, who was then 18 years old and reeling from an art school rejection letter. He asked her to come work at Spumco. Receipts signed by Kricfalusi and saved by Rice show he paid for her stay at the Voyager Motor Inn in June 2000.

Rice worked for Kricfalusi on and off from age 18 to about 25, starting as an inker and moving on to layout and character design. In 2000, Byrd and Rice both worked at the studio, but the childhood internet friends never spoke face-to-face; Swarr remembers the women working at opposite ends of Spumco. Mora and Swarr believed that Kricfalusi hired Rice as a replacement for Byrd. At 19, Byrd thought so too. She said it seemed to her at the time that Kricfalusi was replacing her with a younger woman.

Byrd left Kricfalusi for good in 2002. Once she was gone, he focused more attention on Rice. In emails, Kricfalusi demanded her professional loyalty. He also continued to pressure her for affection. Through a lawyer, Kricfalusi denied harassing Rice, saying, "John's avid pursuit of her romantically was all after the company went out of business and he was no longer her employer." But around the time of the new Ren & Stimpy show, which was produced by Spumco and employed Rice, he wrote her a letter expressing sadness over his breakup, and also told Rice she was pretty and that he wished he could cuddle with her.

On Oct. 19, 2004, when Rice was working at Disney, 49-year-old Kricfalusi contacted Rice via her work email. He wrote that he’d been resentful, as a 41-year-old man, of the classmate Rice liked when she was 15. “You used to make me very jealous … and you would never admit you liked me in a romantic way.” At the end of that email, he begged her to be in a relationship with him, writing, “I would worship you and bve [sic] your best partner and friend and everything that would be good to be.”

Rice said the sexual harassment got worse when she worked from Kricfalusi’s home office, particularly when they were working on a music video commissioned by “Weird Al” Yankovic. (The musician said he was not aware of any of the behavior described in this story and declined to comment further.) In an email reviewed by BuzzFeed News, Rice told Byrd in 2008 that Kricfalusi “was doing all sorts of bizarre stuff- waiting naked in his living room for when I let myself into his house to work in the morning, walking around with his weiner hanging out of his pants, telling me that his friend's advice to ‘get’ me was to just rape me one day.”

Through an attorney, Kricfalusi denied exposing himself to Rice, and said that the rape comment was just a joke.

Rice’s voice rose in frustration. “I know what everybody’s gonna say: Why didn’t you just leave? Well, because this asshole told me when I was 13 that I was special, and I don’t have any self-esteem, so I believe it.” And the fact was that he had hired her, when she had no prospects, right after she was rejected from art school. As she had argued in forums online, she really did think he was a great artist. She thought that she owed her mentor and friend, and she felt a certain twisted pride in putting up with his harassment.

“I know what everybody’s gonna say: Why didn’t you just leave? Well, because this asshole told me when I was 13 that I was special, and I don’t have any self-esteem, so I believe it.”

Rice said she finally did leave after two incidents that happened in relatively close succession: The first was his half-threat of rape during the Weird Al job, and then, she said, she found child porn on his computer. Rice said she found images of girls she didn’t recognize, naked; she remembered one photo in particular, with a naked girl who appeared to be around 10 years old, lying on her back with her legs spread and an expression on her face that Rice described as fearful. An ex-girlfriend of Kricfalusi’s, who asked not to be named in this story, said she, too, saw naked images of prepubescent girls who appeared to be between 12 and 14 on his personal computer around 2007.

Through an attorney, Kricfalusi said he has never possessed child porn, and that he had never been contacted by the police regarding an investigation. His attorney added, “I assure you that there are significant differences between your outline and what actually happened and when.” The attorney did not provide specifics prior to publication.

Rice said it took her three attempts to report the child porn she saw on Kricfalusi’s computer. On two occasions, she said, she panicked while filling out an online form for the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. Rice successfully reported seeing child porn to the police at the end of 2017. Byrd said she spoke to a detective on the case as well, thinking that, even though the statute of limitations for her allegations was up, her account might bolster the investigation. The LAPD declined to comment on the case, but Rice said she was told that they wouldn’t be able to get a warrant. It was after receiving that phone call from the police that she decided to go on the record. She hopes making her story public will relieve her of the burden she feels to warn young women thinking of working for him.

“It’s been easy for us to disconnect the artist from the person, because as an artist, he’s unparalleled,” Mora told BuzzFeed News. He said it was hard thinking about things he and Swarr could have done to help Byrd and Rice, and he struggled to reconcile his feelings about Kricfalusi. “If I ever won an award, he would be one of the first people I would thank,” he said. “But there is that other side of John — John the man, not John the artist — and that’s the part that is conflicting.”

In a busy restaurant in Burbank, Swarr still expressed some sympathy for Kricfalusi. “I owe John a lot,” he said. “He has a lot of problems, and he can’t see them. It’s tragic. I don’t feel bad enough to not talk about this, though.” Swarr said he began distancing himself from Kricfalusi after Rice told him around 2002 that their mentor had started hitting on her when she was a child. “I wish I could’ve done more back then. This” — talking to a reporter to corroborate the women’s stories — “is the only thing I can do now.”

The Paramount Network — the current iteration of Spike TV, which ran Ren & Stimpy’s 2003 reboot, Adult Party Cartoon — said it had never received reports of sexual harassment against Kricfalusi and has “specific policies and procedures to ensure our employees feel empowered to report inappropriate behavior.” A spokesperson for Cartoon Network and Adult Swim said that the networks were not aware of any sexual harassment claims against Kricfalusi, that “harassment will not be tolerated” by their parent company, and that neither network planned to work with him in the future. Nickelodeon declined to comment on Byrd and Rice’s allegations. But the morning after the story was published, Kricfalusi’s portrait was removed from the studio.

Allegations of sexual misconduct have long been treated as a proverbial footnote for important men. In an industry that continues to exclude women and that has a widespread problem with sexual harassment, as more than 200 women and gender-nonconforming people working in animation attested in an open letter in October, it’s unclear whether Rice and Byrd making Kricfalusi’s abuse public will lead people to rethink his legacy. What is clear, however, is that #MeToo can’t move forward without reexamining the past.

Byrd is resolute. “He ruined a good bit of my childhood and my early adulthood, gave me PTSD, and forced me to change careers, putting my life 10 years or more behind,” she wrote in an email. In an interview, she said, “He is an abuser in the way that he will pull you into a relationship with him and then tell you who to be and what he wants from you. … Everybody needs to know about it.”

Rice, too, is unequivocal about Kricfalusi: “I became a better artist by working for him,” she said. “I’m not grateful for it. I wish I hadn’t. I wish I were a worse artist now and I didn’t have all this bullshit to deal with.” ●

UPDATE

This story has been updated to reflect that Nickelodeon removed Kricfalusi’s portrait.

UPDATE

A photo has been removed from this story to align with BuzzFeed's editorial standards.