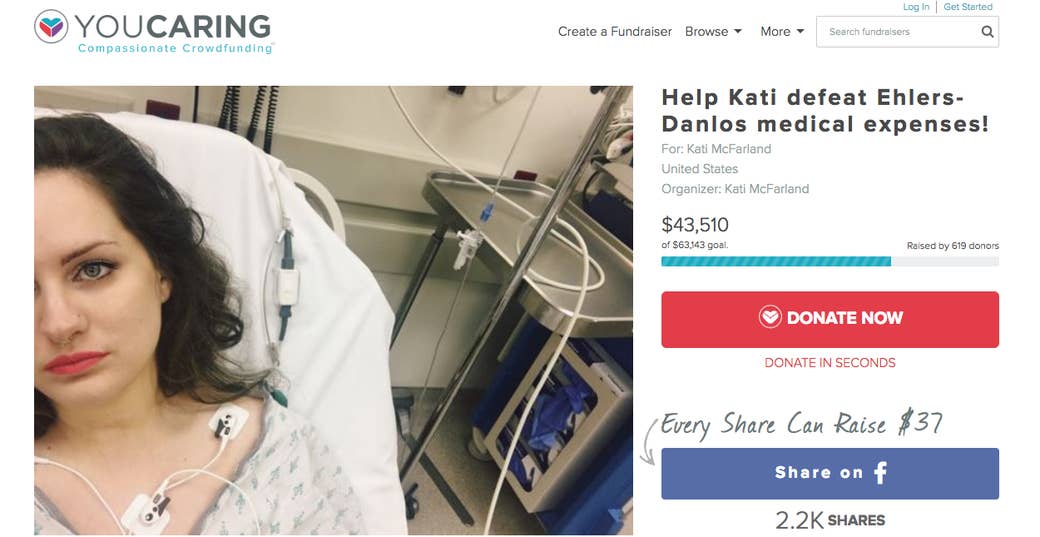

Kati McFarland is 26 years old. If you look at her YouCaring page, you can see she has a septum piercing; she wears great lipstick; she’s skilled at taking selfies. She’s currently finishing degrees in business and violin performance at the University of Arkansas. She loves cats, greyhounds, Russian composers, and hockey. And if the Affordable Care Act is repealed — and the replacement doesn’t cover pre-existing conditions — she says she will almost certainly die.

McFarland has Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a rare genetic disorder that makes it difficult to, in her words, “walk/stand/eat without severe pain/dislocations/vomiting/blackouts.” Even with her extensive health complications, she was able to make ends meet, receiving coverage under her father’s insurance plan, until his sudden death last year. Facing possible eviction and rapidly deteriorating health, McFarland turned to YouCaring, a popular crowdfunding site, where she meticulously detailed her $562-a-month COBRA payment, her co-pays, her prescription expenses, and the medical procedures she needed to survive.

After two months, however, McFarland’s fund had failed to top even $600 of its $61,185 goal. On February 21, she wrote “if I don’t get this fundraiser to $1,500 (roughly $1,000 more raised) by March 3rd, I will lose either my home or my health insurance. Please signal boost and donate if you can!”

Like millions of Americans, McFarland struggles in the margin between being “insured” and actually being able to cover her health care costs. And while her story is tragic, when she first posted it, it wasn’t dramatic enough to go viral on crowdfunding sites filled with similar pleas for help. She’s young, but she’s not an adorable child; she’s extremely sick, but not with a disease that most people understand. Which isn’t to suggest that her story, or her life, isn’t worthy. But her situation highlights many of the underlying issues with a new-found reliance on crowdfunding as a social safety net.

There’s a politics to who gets funded and who gets left behind, who collapses under the weight of the broken health care system and who’s temporarily buoyed. And as Congress weighs a potential repeal and replacement of the Affordable Care Act, it’s essential to think through what crowdfunding can’t fix — and how even the best of intentions can perpetuate devastating, systemic inequalities.

Crowdfunding first drew national attention as a way to fund a new invention, finance a film, or take a once-in-a-lifetime trip. Over the last five years, two major genres of crowdfunding have emerged: one, very broadly conceived, for the fun, fantastical, and entertaining (think Kickstarter and Indiegogo); another for the serious (GoFundMe, YouCaring, and at least a half dozen others). One for tangible things and events, in other words, and another for people. The latter has increasingly become a means to save yourself from life-demolishing bankruptcy, provide supplies for underfunded schools, allow women to take maternity leave, care for disabled veterans, fund your college education, or improve living conditions for a foster father who only takes in terminally ill children. A way, in other words, to at least temporarily patch (some of) the deepening cracks in the vital institutions and programs that make up the backbone of America.

Crowdfunding helps families like those of Joey Rott, of Clay Center, Kansas, whose wife died after giving birth to triplets — leaving him to care for five young children on his own. It assists thousands of families struggling to pay for treatment for children afflicted with cancer, rare diseases, and chronic illness. It helps survivors of injustice, like the family of Michael Brown, cover the costs of funerals and legal battles. (It also helped supporters of Darren Wilson, the police officer who shot Brown, raise more than a quarter million dollars).

In many ways, crowdfunding is just the 21st-century, social media–facilitated version of what’s long been known as “mutual aid” or "benefit society" — systems, broadly defined, in which members of a community collaborate and contribute to take care of each other. Mutual aid could take the form of an old-fashioned barn raising, in which every member comes together to complete the labor that the individual could not, or insurance programs, often organized around ethnicity or religion. By the 1920s, 1 in 3 males were members of a social aid society in some capacity, through groups like the Knights of Pythias, the Sons of Norway, the Women's Life Insurance Society, the Odd Fellows, and St. Luke’s Society.

Mutual aid and benefit societies was used to solve fundamental inequalities: To provide steady income during times of job precarity and discrimination; to ensure the survival of women and children when primary wage-earners regularly died on the job or suddenly, of infectious diseases. To offer security when so many parts of life seemed to conspire to prevent it, especially if you were an immigrant, a woman, or a person of color.

The national welfare programs of the Great Depression gradually superseded mutual aid programs — but there were still community-based means to make up the gaps in the newly nationalized safety net. Rent parties, spaghetti feeds, pancake dinners, women-less weddings, bake sales, car washes, silent auctions, weekly offerings at church, those coin jars at the grocery store or gas station — all relied on communities, and the ties within them, to make ends meet for those who struggled.

But a host of factors — including the skyrocketing cost of health care, the housing crisis, the lingering effects of the economic downturn, the opioid epidemic, and the shift toward part-time perma-lance labor — have made pennies and pancakes insufficient. Forty-seven percent of Americans don’t have even $400 on hand to deal with an emergency. An accident, a broken-down car, a sudden job loss, a sick parent — it takes very little to completely derail a family’s life.

The percentage of bankruptcies due to health care costs is notoriously difficult to determine; estimates range from 21% to 66%, with significant fluctuation, as yet uncalculated, due to the implementation of the Affordable Care Act. But millions still struggle to cover the cost of health care, whether insured (and attempting to cover premiums, co-pays, out-of-pocket expenses, and uncovered treatments) or without insurance altogether. Crowdfunding initiatives have helped ease the burden: One study, published in 2014, estimated that 4% of would-be bankruptcies in the United States have been prevented by health care crowdfunding.

Mutual aid was for anyone in a community who could afford to pay dues. Universal health care provides care no matter who you are and what you’re suffering from. But crowdfunding — to an even greater extent than the nondigital forms that came before — is almost entirely contingent on the ability to craft a compelling narrative.

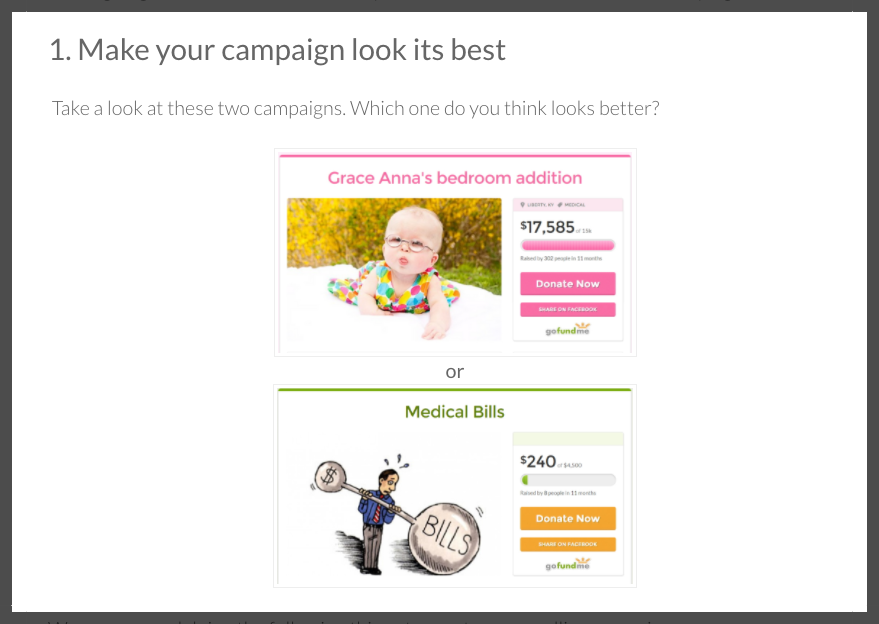

Both GoFundMe and YouCaring provide step-by-step instructions for what they call a “successful campaign.” “Use a great photo or make a video,” GoFundMe advises. “This is your shot at a first impression and it should create a strong reaction, like ‘Wow!’ or ‘Awe!’ or ‘I need to know more about this’ ... Try to use photos of the people involved whenever possible. They get stronger reactions than a graphic or text. Be sure to avoid blurry or low-quality images.” YouCaring suggests users pay particular attention to choosing their fundraiser’s name: “Many people will decide whether to read about your cause based solely on your fundraiser’s name.” Or, as GoFundMe puts it, “Which title sounds better? ‘I Need Money!’ or ‘Julie’s Rally Against Cancer?’...the second one, right?”

There’s nothing nefarious or devious about this advice — it’s simply Online Marketing 101. So is the way crowdfunding sites advise users to create feasible goals, share widely with their social networks, provide regular updates, “spark compassion,” and “tell your story honestly.” There’s always been need in modern capitalist society. There has not, however, always been the requirement to market one’s need.

Of course, packaging need isn’t necessarily new. Every time we ask a family member or friend for money, we’re presenting our need in a way that makes it more likely they’ll respond; some people are better at it than others. But that’s also why most would rather not rely on their family, friends, or an ability to convincingly ask someone for money as a means of survival. It’s subjective and depends, at least in part, on a flair for drama. Marketing a need through crowdsourcing demands similar skills — creating or choosing a compelling image and an eye-grabbing, keyword-searchable title — but a campaign must also transform the underlying need into a persuasive narrative. As YouCaring points out, “Julie’s Rally Against Cancer” is more compelling than “I Need Money” — one situates “Julie” as the hero fighting a good fight; the other de-romanticizes the struggle down to its most essential (and truest) form: My need? Money.

This paradigm sets up a dangerous expectation in which giving is contingent upon being moved, entertained, or otherwise satisfied with the righteousness of a fight. I’ll give, this arrangement suggests, but only if you give something to me — tears, sadness, hope, cuteness — first. As Jeremy Snyder argues in the Hastings Center Report, this paradigm also creates a “strong incentive to sensationalize or embellish their stories in order to receive donations,” in part because the narrative has to be striking enough to compel individuals outside of one’s existing social network to give. You’re not just selling to your family members, in other words — you’re trying to sell to the entire internet.

That’s part of crowdfunding’s selling point: the ability to “reduce friction,” to use a tech term, within the giving process. It’s easier for individuals to donate (sign into PayPal and you’re good to go) but it’s also easier to reach those potential donors: Instead of depending uniquely on your own social circle, you can also appeal, with proper virality, to the friends of your friends of your friends of your friends. The security of a site like GoFundMe, which guarantees that all funds will go to the beneficiary or your money back, decreases natural hesitancy to donate to people with whom you might not have a direct connection; while the ability to donate online, through a series of quick clicks, provides immediate gratification.

As the friction of giving has decreased, the marketplace of giving — and the options within it — has expanded exponentially. And while many modest funding cases can be fulfilled simply through reliance on one’s social network, the success of larger ones — anything over a few thousand dollars — is contingent upon that gripping narrative, that clickable photo, that triumph over adversity. Those cases are the ones that get featured on the sites’ homepages, that attract local and national media coverage, that get tweeted by celebrities, that make their way, like the father of five kids mentioned above, into People magazine — while other, less compelling ones languish below their goals.

In addition to FAQs and marketing tips, GoFundMe and YouCaring provide customer service to help users fine-tune their narratives for success; GoFundMe even has round-the-clock staff on duty who will respond to queries within five minutes. (It behooves GoFundMe for its funds to succeed: It receives 5% of all funds raised. YouCaring’s business model relies on donations, whether from users, who can donate to the platform when they give, as well as gifts from company’s “amazing processors,” e.g. PayPal, and “other partners.”)

But not even the best customer service can transform a narrative that Americans, at large, have largely considered unworthy. Most of the successful campaigns on a crowdfunding homepage fall under the rubric of “fighting unfairness,” a designation that expands to include one of GoFundMe’s most successful campaigns of all time (for Standing Rock) but mostly signifies struggles against diseases that seemingly strike at random: cancer, genetic disorders, and other afflictions ostensibly out of the victim’s control. Such conditions are often referred to as “faultless.”

It’s far harder to fund so-called “blameworthy” diseases — addiction and mental health in particular — that are popularly conceived as either the fault of the victim or somehow under their control. You rarely see campaigns for adult heart disease, for example, or “getting my life together as a single mom” — both are viewed as the result of “choices” instead of “needs.” If there’s already a hierarchy of affliction and need in this country, then crowdfunding often works to exacerbate it.

With that said, the ability to seek funding online — and target specific online communities — has been crucial for people struggling to fund gender reassignment, cover adoption costs, and pay for IVF. Yet many of those with the greatest need are those whose story or situation simply is not compatible with the crowdfunding model. Successful campaigns don’t just depend on robust digital social networks, but also on digital literacy in general. You need to be digitally savvy — or have someone advocating for you who is — in order to even make an account.

And while many campaigns have successfully advocated for elderly people, the disabled, children, and others without traditional digital marketing skills, crowdfunding still disproportionately favors those living on the “right” side of the digital divide. Immigrants, people with mental illnesses, non-English speakers, and others with closed, small, or nonexistent social networks are less likely to have the skills or ability to create a successful crowdfunding campaign.

Crowdfunding is fantastic at addressing need — but only certain types, and for certain people. It can activate our most charitable selves, but it also, through its very format, often exploits our worst societally ingrained biases — toward melodrama and causes we can “root for” without complication, but also toward an understanding of the world that prizes individual choice and “return on investment,” even when old-school foundations and philanthropies provide a much more efficient and effective means of investing in care, research, and societal assistance in general. Some charities have been criticized for organizational bloat and waste, but as Snyder points out, such “professional aid organizations,” whether Habitat for Humanity or the Susan G. Komen Foundation, are also incredibly adept at figuring out the most effective ways to identify need, how to bundle donations to effectively address that need, and how to advocate for the sort of policy changes that could eliminate that need. "All areas," according to Snyder, "in which individual crowdfunding campaigns fall short."

And while crowdfunding platforms themselves may not be discriminatory (although they do prohibit “controversial” campaigns like abortions and euthanasia) the crowdfunding paradigm is not itself fair. It discriminates without intending; much like society at large, it benefits those who are skilled and young and attractive and connected.

Which returns us to the question of its sustainability, especially as a mode of mutual aid: As Dr. Ida Hellander, director of health policy for Physicians for a National Health Program, put it, “I wouldn’t even say it’s a band-aid — it’s a sort of desperate attempt to help a few people.”

“It shows how desperate people are,” Hellander continued. “And it shows the magnitude of the crisis and the fact that the political will is not there to help people.”

Two days after issuing her plea for more donations, Kati McFarland used a walker (not the wheelchair she needed but couldn’t afford) to enter a town hall meeting for her senator, Tom Cotton, to advocate against the repeal of the Affordable Care Act. “We are historically a Republican family,” McFarland said. “We are a farming family. We are an NRA family ... Without the coverage for pre-existing coverages, I will die. That is not hyperbole. I will die. ... My question is will you commit, today, to replacement protections for those Arkansans like me who will die, or lose their quality of life, or otherwise be unable to be participating citizens trying to get their part of the American dream? Will you commit to replacements in the same way that you committed to the repeal?”

Without specifics, Cotton attempted to reassure McFarland that she would be able to maintain coverage. But the video of McFarland’s request — echoing the questions and fears of many Americans in health precarity — went viral and gained national news coverage. Within days, her YouCaring donations topped $26,000. (At the time of this writing, she's raised $43,000 of her $63,000 goal; her story is currently featured on the YouCaring homepage).

“Money helps, it’s true,” she wrote. But what really helps are people’s own stories. The more she reads of each individual struggle, “the more I’m convinced we can change the hearts and minds of those who would take away the protections that keep those struggles from getting worse.”

“Maybe that’s a pipe dream,” she continued. “But in any case, your stories and generosity show me that the American people will not take the dismantling of our rights lying down.”

On March 8, the same day the GOP revealed its new health care plan — which would cover pre-existing conditions, but would not necessarily keep the premiums for those pre-existing conditions at a tenable level — McFarland appeared on CNN.

“It seems like punishment for the marginalized among us,” she told Don Lemon. “When we’re already reduced to extremely high premiums, we’re reduced to crowdfunding ... it tells Americans that our lawmakers don’t care about the marginalized among us, it tells us that they don’t care if we live or die.” The proposed plan, she believes, will create “that much more of a financial and psychological burden.”

“Being poor and anxious is bad enough when you’re healthy,” she said. “But when you’re intractably ill — it’s worse.”

Stories like McFarland’s matter. Part of that story, though, is the fact that even with a compelling narrative and a massive publicity push, she still needs to raise $40,000 to even sustain her current level of health. No form of health care ensures a happy ending; GoFundMe and YouCaring and dozens of similar sites provide funding for thousands in desperate need.

“Our end goal is health care for everyone,” Jesse Boland, the Director of Online Marketing for YouCaring told me. “In an ideal world, YouCaring doesn’t exist. WE'd love to only fund happy things.” The fact remains: no matter how effective crowdfunding becomes, it will never be a viable solution — in part because it’s actually a symptom of a much larger, and systemic, social ill.

That doesn’t mean we should stop giving. But it does mean we should stop mistaking stopping a leak for fixing the plumbing.

CORRECTION

Kati McFarland is currently finishing degrees in business and violin performance at the University of Arkansas. A previous version of this post incorrectly said she was completing a BA.

Want more of the best in cultural criticism, literary arts, and personal essays? Sign up for the BuzzFeed Reader newsletter!

Outside Your Bubble is a BuzzFeed News effort to bring you a diversity of thought and opinion from around the internet. If you don’t see your viewpoint represented, contact the curator at bubble@buzzfeed.com. Click here for more on Outside Your Bubble.