In 1995, Charlize Theron was newly arrived in Hollywood after stints as a model and a dancer, living in a fleabag motel, and running out of money. Her mother had sent the 20-year-old Theron a check from South Africa, but when she went to the bank to cash it, they refused her. Fed up, Theron threw what has been repeatedly called “a tantrum.” That argument, coupled with her beauty, caught the eye of an agent, who promptly handed over his business card. Fast-forward a few months, and there’s Theron in white lingerie, towering over Los Angeles in billboards for 2 Days in the Valley.

This anecdote finds its way into almost every profile of Theron, and Theron herself has regularly described it as “Lana Turner-esque,” referencing the classic Hollywood star who, according to popular lore, was “discovered” at Schwab’s Soda Fountain in Los Angeles in 1937. The tantrum, the beauty, and the comparisons to Turner — best known for her ice-cold platinum look and secretly sordid private life — provided the star mold for Theron’s early image. Like Turner, Theron was raised in rural isolation; like Turner, her father was murdered, leaving her and her mother to survive on their own. Neither had traditional training as actresses. Both were routinely underestimated, initially cast as pretty faces with beautiful bodies.

But unlike Turner, who was exploited and abused by a series of men in her private and professional life, Theron charted a different career trajectory for herself almost immediately. Over the course of the next two decades, her image has shifted from cool girl to bitch, and now from bitch to broad. Even with — or despite — her traditional beauty, she’s achieved a position of cultural and industrial power akin to Bette Davis and Katharine Hepburn, who, like Theron, prided themselves on ignoring the unspoken rules of proper (female) star behavior.

Today, Theron still labors to get people to talk about what she’s reading, her craft, or her politics, instead of what she ate to gain weight or what she’s doing in her private life. She continues to fight the idea that the private lives of female stars are not only public property, but take precedence over whatever they do onscreen. For that, she’s been labeled a bitch, a diva, and an ice queen. But she’s also fashioned one of the most enduring and unexpectedly varied careers in the business, positioning herself as one of the most bankable — and powerful — stars in Hollywood.

Theron has said that she’s “very attracted to characters who don’t necessarily make it easy to be loved.” But she’s only been able to refuse niceness, onscreen and off, because of her beauty: It’s the capital she keeps cashing in order to get interesting roles that will de-emphasize, or at least trouble, the privileges that attend being a thin, white, straight woman in today’s society.

So what happens when that beauty, at least by Hollywood standards, comes of age? First, you keep conducting your career as a man would — or, more precisely, you redefine what a woman’s career might look like. And then you lobby for, demand, or create the very roles that Hollywood wouldn’t otherwise. As Theron enters the third decade of her career, she hasn’t just figured out how to game the system. She’s trying to change it entirely.

After 2 Days in the Valley, Theron’s agent arranged for her to audition for Showgirls. She was purportedly offered the lead role, later given to Elizabeth Berkley, but turned it down — and fired her agent. “We can see where he saw my career going,” she later told W magazine. She didn’t work for nearly a year; all of her offers were for “sex-kitten” roles that required her to take her clothes off. And then she won a part in That Thing You Do!, Tom Hanks’s directorial debut.

The role was significantly reduced during the editing process, but served as an opening for Theron. Over the next five years, she’d go on to play a string of wives and girlfriends who only periodically took off their clothes. Those films (The Astronaut’s Wife, Reindeer Games, and a half dozen more) were all relative duds, yet Theron was celebrated as one of the most beautiful women in the world — and became famous enough to attract funding for Monster. It was a role that promised to change the conversation about her.

But that conversation was not easily changed. Every star, no matter their gender or their beauty, their age or their acting, gets slotted in a particular place in Hollywood as soon as they give a performance worth writing about. For Theron, that place has always been “rural cool girl”: the male fantasy of a hot girl who doesn’t take anything too seriously, who loves to hang with the boys, who’s low-drama and won’t hassle the men in her life with bullshit like asking for things.

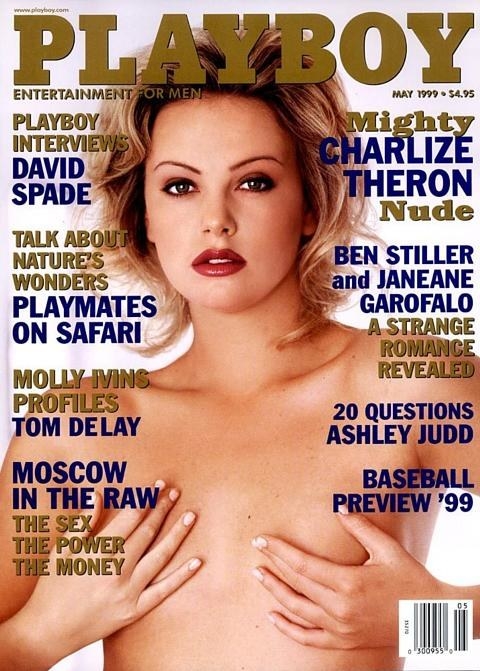

Early profiles always mentioned Theron’s “discovery” story, but reveled in her past: how she grew up on farm, how her best friend was a goat, how she swears like a sailor, how she just happens to be the most beautiful woman in the world, with a body to match. Pictures of her — in Playboy, Esquire, Vanity Fair — highlighted the second part of the equation, while the interviews took care of the rest.

She wasn’t just raised in rural South Africa, but as many articles emphasized, on a “dirt farm” — which really just means they farmed without irrigation, but sounds much more rural, and, well, dirtier, than “farm.” In one of her first profiles of her, People magazine reported that Theron, growing up an only child, relied on a goat named Bok to be her best friend. “I grew up surrounded by animals,” she told EW in 1997. “I was milking cows before school at six in the morning and making butter; I can do all that shit.” She’s a tomboy, who, according to the Ottawa Citizen, “loves a big barbecue”; she learned all about engines from her father, who was a mechanic. “I don’t remember when I learned how to drive,” she told the South African Sunday Times. “I just woke up one day and I could.” According to Theron, when she was filming The Italian Job — with stunts that required precise technical driving — Mark Wahlberg would do a 360 and start puking while Theron yelled “What’s up, girl?” at him.

Early profiles reveled in Theron's past: how she grew up on farm, how her best friend was a goat, how she just happens to be the most beautiful woman in the world, with a body to match.

In at least six different interviews, Theron ate steak. Breakfast: steak and eggs. Lunch: steak salad. Dinner: strip steak. And she was seemingly always drinking: shots of tequila, bottles of Rolling Rock, dive-bar booze. “She has the appetite of a lumberjack,” according to Good Housekeeping. “She doesn’t subscribe to Hollywood’s passion for grasshopper-thin figures,” said Biography. She chain-smoked. She had tattoos. She said “fuck” a lot. For Vogue, she had “the swear-heavy vocabulary of a randy stevedore.” In Vanity Fair, Kenneth Branagh related an anecdote from their time together on the set of Woody Allen’s Celebrity: “We were stuck in the back of a Teamsters van waiting for the rain to stop,” he said. “It was the filthiest conversation I’ve ever had. The two Teamster lads couldn’t believe their ears.”

To promote her early roles — mostly as girlfriends, wives, and love interests to middlingly handsome men, from Ben Affleck (Reindeer Games) to Keanu Reeves (Sweet November), she was placed on the covers of magazines, often without pants or a top. “Why be afraid of your sexuality?” she told Vanity Fair. “I have to use that. ...Nudity, if used correctly, is extremely powerful.”

Nudity served to get Theron steady, if unremarkable, work — and it soon dominated her image. In 1999, Playboy published nude photos of Theron that had been taken years before when she was still modeling. Theron attempted, unsuccessfully, to sue the magazine, but the effect on her image was complete. Regardless of consent, the cover of Playboy had the same connotation: Theron was a hot girl, a Playboy girl, not an actress of substance.

Her cool girl image began to morph in other, darker ways. Theron was purportedly undeterred by the male-dominated film industry, because, as she told the Courier-Mail, “the more men you throw my way, the more I just become alive.” She supposedly snagged boyfriend Stephan Jenkins, lead singer of Third Eye Blind, by going backstage at a concert at the Hard Rock Cafe in Hawaii. That relationship dissolved, but when she started dating Irish film star Stuart Townsend, it was framed as an on-set seduction: Theron “has a reputation as a man-eater in Hollywood,” as the Sunday Mirror proclaimed.

“Man-eater” was the only way to describe a hot woman who 1) wasn’t married; 2) didn’t talk about her plans to become married; and 3) never affected an aura of “niceness” in interviews. The rural cool girl had become a vamp: a long-standing Hollywood stereotype that expands to describe darkly sexual women like Angelina Jolie (who, around this time, was wearing a vial of husband Billy Bob Thornton's blood around her neck) and Theron, as the narrative of her childhood was revealed to be much darker than previously suggested.

In early interviews, Theron claimed that her father had died in a car accident when she was just 15. But in 1998, police reports emerged detailing how Theron’s mother, Gerda, shot and killed her husband after he threatened to kill both her and Charlize. The shooting was ruled an act of self-defense; no charges were ever brought. When the real story broke, Theron never tried to deny it, but did not comment directly on it, save a single primetime special with Diane Sawyer “so that everyone would know and so we could demystify the whole thing,” as she later told Interview.

“I can’t tell you how many times I’ve auditioned for a role, only to have my agent come back and say, ‘Listen, Charlize, they saw you in the orange dress and they don’t think you can do it.’”

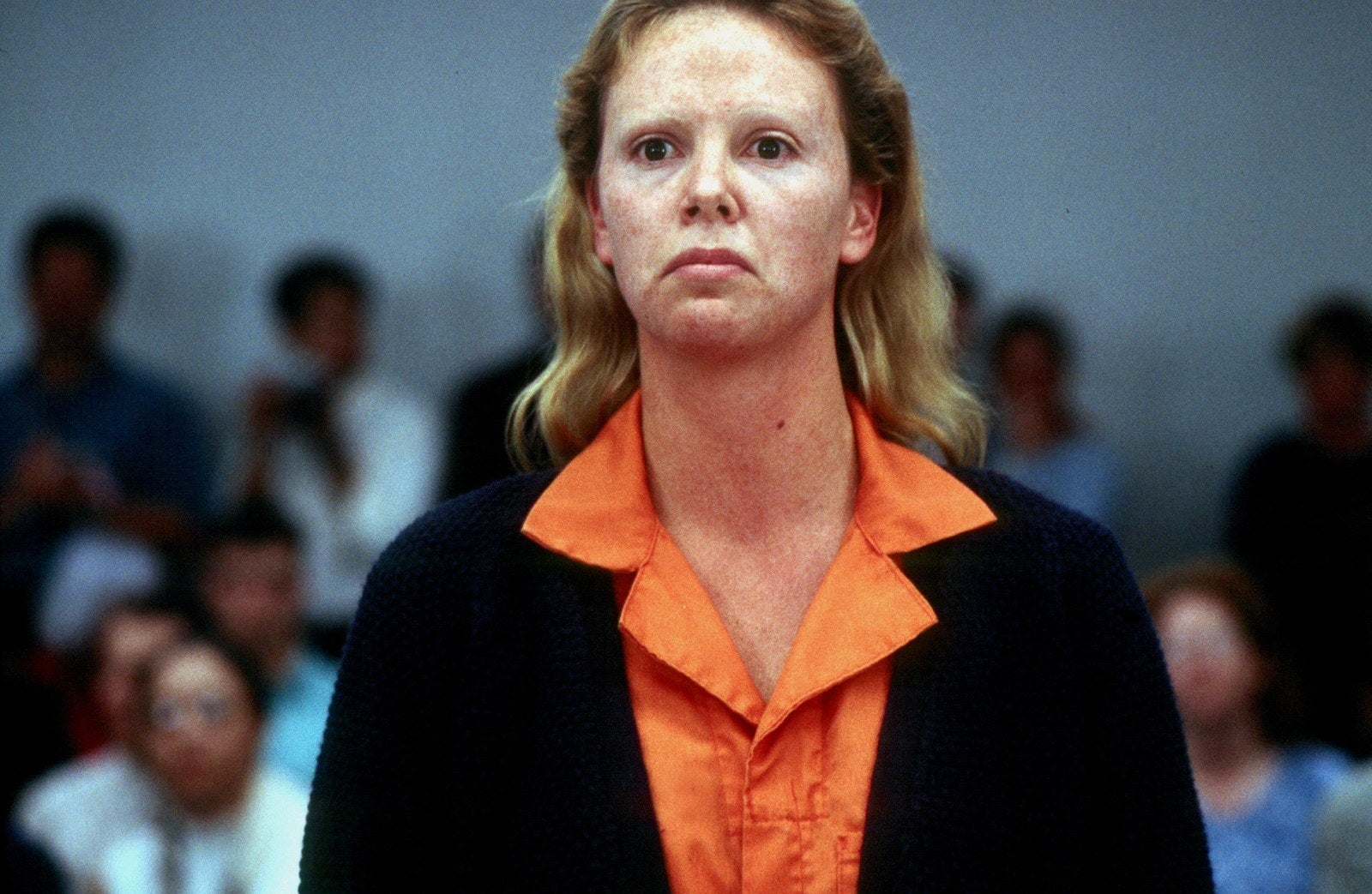

Still, it became a fixture in press to come — a sort of shadow over the cool girl narrative, a central tragedy that could be connected to every role she chose, every decision she made — especially when, in 2003, she dramatically transformed herself for the role of serial killer Aileen Wuornos in a small, indie movie called Monster.

Leading up to Monster, Theron’s role as a cover girl was secure. She was voted the “Most Desirable Woman” of 2003 by the readers of AskMen.com. But the parts she got were generally shit — and the movies themselves by and large bombed. The Astronaut’s Wife earned $19 million back of its $75 million budget; The Legend of Bagger Vance earned just $40 million (budget: $80 million); Reindeer Games grossed $32 million (budget: $42 million); The Yards didn’t even crack $1 million (budget: $24 million). Sweet November performed decently but was so bad it won Theron her first Razzie nomination for Worst Actress. The Curse of the Jade Scorpion will go down as one of Woody Allen’s major flops. Trapped, costarring Kevin Bacon, earned $13 million (budget $30 million); Waking Up in Reno, with Billy Bob Thornton and Penélope Cruz, made just $262,000. Italian Job was a surprise blockbuster — and the first film to truly take advantage of Theron’s nimbleness as an action star — but her role in the film was still supporting.

Part of the problem, according to Theron, could be traced to an orange gown she wore to the Oscars back in 2000. Formfitting, plunging in the back, and paired with soft finger curls, it prompted comparisons to Jean Harlow, landed her on every best-dressed list, and, for the next three years, became a symbol of what she couldn’t move beyond. As she told the OC Register, “I can’t tell you how many times I’ve auditioned for a role, only to have my agent come back and say, ‘Listen, Charlize, they saw you in the orange dress and they don’t think you can do it.’”

“It could be a magazine cover, a movie role or even an orange dress,” Theron continued. “People in this town get stuck on an image and don’t realize that it is the job of an actor to transform.” Put differently: Theron wanted roles that asked her to do more than just be hot, which may have helped her earn her place in Hollywood, but then turned into a cage of her (and her publicists’) own making.

It’s no coincidence that it was a female director who was able to envision Theron as more than the sum of her beautiful parts. That director, Patty Jenkins, was casting for the lead role in Monster, a story based on the real life and death of serial killer Aileen Wuornos. Jenkins screen-tested Kate Winslet, Heather Graham, Brittany Murphy, and Kate Beckinsale. But ever since seeing Theron’s dark turn in The Devil’s Advocate, Jenkins had known she wanted her for the role.

When Jenkins approached her, Theron was confused. “Why me?” she asked. “This stuff doesn’t happen to me…these are usually the things that I have to go out there and sweat blood and kill somebody for.” Jenkins’ reply: “Honestly, I just looked at you, and I looked at everybody else, and I said to myself, ‘I could kick the other actors’ asses. You, I’m not so sure.’”

This aura of toughness, which emerged over and over in the conversations about Monster, would help shift Theron’s career trajectory to its current action-hero apex. It wouldn’t have been possible, however, without Jenkins’ understanding of Theron’s ability — or Theron’s own role in making the film, which became the first undertaking for her production company Denver & Delilah.

Theron would go on to win an Oscar for her performance; afterward, her asking price rose to $10 million per picture. But first, she had to deal with every interviewer obsessing over how a pretty, thin person could possibly be “brave” enough to gain weight and, as it has since become known in the industry, “go ugly.” “Charlize Theron Sacrifices Great Looks for Great Part in Monster,” a typical Vancouver Sun piece exclaimed. “When the first photo stills from Monster were published, no one could believe that Theron … would downplay her ‘greatest asset’ to become a homeless lesbian prostitute and serial killer.”

Theron’s performance was far more than the dental prosthesis, makeup, and weight gain that accompanied it — or the press-ready narrative of “transformation” that became central to the Oscar campaign that coalesced around her. Theron, for her part, did her best to resist that narrative — in part because it equated “looking poor” with bravery, but also because it elided the actual, well, acting. She was particularly annoyed with critics who suggested she decided to “get ugly” without motivation — or without grounding it in the facts of Wuornos’s life. “People were like ‘You better not make Charlize Theron ugly!” Theron told The New Yorker. “Fuck that. I didn’t work on Aileen from the outside in. After I read the writing she did in jail, she was in my body, and I was in hers.”

According to Theron, each aesthetic decision was made with tremendous care: “Her body was the way it was because she had a child at 13,” Theron said in the Denver Post. “She was homeless and ate whenever she could, and usually it was crap ... the way her skin looked, the way her teeth looked, the way her eyes looked — those were all things because of her lifestyle, because she’d been living out in sun and didn’t have a home.”

Theron’s transformation wasn’t a stunt, in other words, or an excuse for her to talk about what she ate or how she had to diet to get back to Oscar-dress-worthy weight. But if the press wasn’t focusing on the changes in her body, they were trying to connect the rawness of her performance to her own personal history — and her father’s death. The Toronto Star claimed that “when she talks about Wuornos, you can see it hovering before the surface”; the Sydney Morning Herald suggested she was capable of the portrayal only because “her life story reads like something scripted by David Lynch.”

Part of this interpretation stems from the myth of method acting, which suggests that good acting is rooted in accessing a moment of personal experience, whether it be trauma or joy. Even after Theron won the Oscar, her speech — in which she thanked her mother for all that she’d done for her — was interpreted as code for something more. But Theron forcefully rejected the idea of her father’s death as the organizing and animating principle of her life and talent.

As she recently told Esquire, “It always ends up in articles. Monster was the instant connection — ‘Oooh, ahhh, I’m connecting the dots.’ No, fucker, you’re not connecting any dots. Please. My mom didn’t ask for any of this stuff to ever be. I hate that every article she has to read, that’s the thing — a life is full of color and depth and highs and lows, and it really feels like the easy shot, the easy presumption of where somebody’s depth comes from.”

That trauma remained the “easy shot” — or, as she later put it to Vogue, “like my fucking tattoo” — when it came to interpreting Theron’s post-Oscar choices, especially her choice to play a non-glamorous Minnesotan mine worker in North Country, or a no-nonsense cop in In the Valley of Elah. But it also marked a turning point in Theron’s career when, having accumulated sufficient industrial capital, she began to refuse perfunctory PR niceness.

She walked out of an interview while promoting North Country in Rome when she was asked, again, about “going ugly.” When a W magazine writer broached the subject of her transformation, she said, “Oh no, you better not be bringing up ‘ugly.'” In Esquire, she went in-depth about contemporary politics and the future of Roe v. Wade, then told the interviewer, “You’re going to have to dumb me down, aren’t you? That’s right. Go ahead. You wouldn’t want me to sound scary. Dumb me down.” At a photo shoot for Vogue, she yelled at the profiler, who had been “warned” about Theron: “What are you going to write about? 'Charlize Theron: Still an asshole?'”

The inclusion of those quotes and mild combativeness underlined the latest development in Theron’s image. The vamp had aged; shed the cool, chill elements of her initial image; and transformed into a bitch.

Part of that aura of bitchiness derived from her continued insistence on privacy. She’d pose for Vogue photo shoots every other year, but she never once appeared on the cover of an American gossip magazine — largely because she gave them so very little to talk about.

Part of that aura of bitchiness derived from Theron's continued insistence on privacy.

Theron did this deliberately: She avoided Hollywood paparazzi hangouts; when she and Townsend were together, they rarely went out in public. “Some people are really into that world, of being photographed, being at the party, being with the guy, being in the Bentley,” she said. “Good for them, because it’s so entertaining to watch. It’s just not me.”

Theron may have been naturally inclined toward privacy, but she also understood the ways that focusing on her private life would make it even more difficult to disappear into her parts. Growing up, the actors she admired most — Gene Hackman, Dustin Hoffman, Meryl Streep — were the ones whose private lives hadn’t become public property, who could show up and be a “clean canvas,” as she put it, for whatever the performance demanded. “There’s a sadness in that the longer you stay in this career, the harder it becomes to get people to sit in a theater and not focus on your looks,” she told Vogue in 2007, while promoting In the Valley of Elah, another “unglamorous” role. “Maybe that’s why I try to keep my private life so private and why I don’t want to be an In Touch celebrity. It’s why I don’t have any patience for the paparazzi. It’s just not something that helps me at all.”

Here, Theron is talking about the long-standing separation between performers known for their acting and performers known as stars. Stars act, but their fame is rooted in the combination of their public performances and “private” lives. If Theron had become a more typical star, she would have taken roles that underlined and amplified her folksy cool girl–ness. She’d have starred in a rom-com. She’d have gotten married instead of flatly dismissing the idea with “I never had the dream of the white dress.” She’d have been purposefully paparazzied in situations that kept her private life in conversation, instead of completely dropping off the map for years at a time, which she did twice over the course of the 2000s.

When Theron adopted a son in 2012, she did not sell the story of their home life, or pictures of them, to a magazine. She did not post pictures of him — or his sister, adopted three years later — to social media. She kept appearances in which they could be photographed together to a minimum. When she started dating Sean Penn in 2014, she acknowledged that their relationship had been more publicized than any of her previous ones, but also spoke flatly about their partnership. “I love Sean and I love our relationship, because we make life better for each other,” she told Esquire. “But he doesn’t fill a hole in me and I don’t fill a hole in him. We are two very healthy adults and we have one hell of a time together and I think that’s important.”

But even if Theron refused the narrative, or the idea that who she was dating was the most interesting thing about her, the press continued to push it. At a press junket in 2015, all the questions were about Penn and her son and, as Theron put it, “what I eat.” “It’s really a roundabout way of getting as much private shit as they can,” she said. Theron resisted that push — which, according to people I spoke to who’ve worked junkets and red carpets with her, is part of the reason that she’s known as no-nonsense, with little time for small talk, niceties, bullshit, or other types of performative posturing expected of celebrities.

And she's basically given up on the traditional celebrity profile — long considered obligatory for stars of all levels. As she recently told Bill Simmons “I'm not a secretive person, but I am a private person, and other than podcasts, it's really hard to kind of have you as a person come across. I just got tired of sitting down for interviews and having some writer just write whatever they wanted to write.” Put differently, she got tired of writers mapping an understanding of her — as cool girl, as survivor of childhood tragedy — onto her otherwise complicated self. “There's a sense of irony that gets lost,” she continued, “especially with me, and I think with women in general...for some reason with men it's a little more forgiving if a writer takes their own idea of what the interview was, but I feel like with women it's so unforgiving.”

While there are many men who’ve opted for this route, it’s a rarity for a woman, in part because a woman’s refusal to share her private life is generally considered selfish, snobby, bitchy. But again, Theron could lean into that bitchiness because she had her beauty as insurance — and could essentially pick whatever project she wanted.

Theron could lean into that bitchiness because she had her beauty as insurance — and pick of whatever project she wanted.

Which is why her filmography between the late 2000s and early 2010s reads like that of someone with an expansive understanding of what they can or should do onscreen. She dabbled in action (Aeon Flux, Prometheus), indies (Sleepwalking, Battle in Seattle), meditations on grief (In the Valley of Elah, The Road), summer blockbusters (Hancock, A Million Ways to Die in the West), satire (Young Adult), cartoons (Kubo and the Two Strings), and thrillers (Dark Places).

She embraced what she herself called her “bitch phase” — playing deeply unlikable characters, villains, and literal ice queens. “I’m owning that market for myself now,” she told The Scotsman in 2012. “What a legacy to leave behind: 'she played all the bitches.'”

Theron was joking — but not really. Since 2012, she’s only gone on to play more bitches (another Snow White movie), more villains (The Fate of the Furious), more fearsome women (Mad Max: Fury Road). But her role in Mad Max, like her current role in Atomic Blonde (and the narrative of her personal life, in which she purportedly “ghosted” Sean Penn when his presence was no longer pleasing) have transformed her into a different sort of icon. She’s no longer a bitch. She’s a broad.

A broad, aka the type of old-school Hollywood actress (think Katharine Hepburn, Bette Davis, Mae West) who combined aesthetic and intellectual virtues and coupled them with the confidence of a man. Broads are women, not girls. Broads aren’t “nice.” Broads don’t put up with Tom Hardy’s shit on set. Broads, like bitches, get shit done — on their own terms.

People have been calling Theron a broad for years. Woody Harrelson described her as a “classic broad”: “incredibly talented, and also able to tell more vulgar jokes than you and drink you under the table.” Niki Caro, who directed her in North Country, likened her to the “thirties Hollywood sense” of the word, explaining that “she has this brilliant ability to set the bar very high and the tone very low.”

Broads are women, not girls. Broads aren’t “nice.” Broads don’t put up with Tom Hardy’s shit on set. Broads, like bitches, get shit done — on their own terms.

That's the cool girl understanding of broad. But broad also has another meaning — best explained by Abbi Jacobson and Ilana Glazer, creators and stars of Broad City, who define a broad as “a full woman” who “knows what she wants, knows who she is, and is doing the best she can.” It’s an understanding Theron has independently embraced. As she told Interview in 2012, “You know when girls say, ‘I’m a girl’s girl?'” It has never felt right for me to say that because I don’t know if I’m a girl’s girl. I think I might be a full woman’s woman.”

That fullness, that complexity of image, is exactly what eludes most Hollywood stars — something which Theron has long been aware of and annoyed by. When doing roundtables with other actresses for Young Adult she noticed that the conversation kept returning to “this frustration of not having material out there that really challenges and explores and asks questions about who we really are as women.”

And part of that is because cinema reflects and further flattens the expectations for women in the world. As she told the Ottawa Citizen, “We come from a society that’s very comfortable with the Madonna-whore complex. We’re either really good hookers or really good mothers.”

Most female stars who insist that they’re neither, or maybe both — onscreen or off — end up on the margins of Hollywood. But not Theron, whose persistence in rejecting such flat roles have earned her the label of iconoclast, “refusing to conform to society’s — or Hollywood’s — expectations of her," as Vogue put it. But let's be clear: Theron only allowed that right of refusal because she has a body and face that do conform to society’s standards. It’s Theron’s beauty that has afforded her the ability to refuse such dichotomies — and, like other broads before her, retexture the parameters of female stardom.

Which might be why Theron keeps appearing without pants on the cover of magazines: It’s the obligatory payment of dues that liberates her to do whatever else she wants. In this way, she’s engaged in an age-old feminist dilemma: When you realize the system is stacked against you, do you figure out how to slyly game it, exploiting your privilege, whether as a white person, as a middle-class person, as a straight person, as a pretty person, as a thin person — or do you try to explode it, even if that tactic ends up excluding you entirely?

“Progress,” and the feminist project for women in Hollywood, looks like many things, including, but not limited to: women in roles like spies or superheroes, historically relegated to men; women working with female directors and screenwriters to surface more complicated roles for women; women producing the projects that matter to them; women advocating for — and refusing to work without — equal pay; and women suggesting that their value, as actors, is not contingent on their ability to market or commodify their private lives. Theron has done all of these things, and she’s been doing them for the vast majority of her career. But progress also includes making way for different types of talented and worthy women to enjoy this sort of success on their own terms.

It’s not Theron’s fault that her face and body on the cover of magazines and film posters fortifies the notion that there’s basically only one way for women to succeed in Hollywood — namely, by making your face and body as close to hers as possible. But the persistence of that unspoken ideal suggests that it will take much more than troubling the archetypes of female behavior, more than owning the role of bitch and transforming it into the broad, more than showing that hot women over the age of 40 can fight.

So much of being a broad, after all, is conducting oneself “like a man.” But men get to age in Hollywood. And women — even women as beautiful as Theron — do not age so much as disappear. To “win” as a woman in Hollywood, then, is to participate in a machine that will soon exclude you. And as the careers of many previously powerful female stars suggest, no amount of plastic surgery or body modification can change that.

What can work — as Theron’s extensive participation in the production of Atomic Blonde seems to suggest — is taking over the levers of power, and producing the sort of roles (for yourself, and, more importantly, for other female stars who don’t look like you) that challenge the accepted knowledge of what audiences want and, by extension, what women can be or do onscreen.

Theron has long manipulated her pretty-girl privilege to get the roles and freedom she wants. But can she use it to get those same roles and freedom for others? ●