Does Ready Player One know that it's a dark story recounted with oblivious lightness, in the same way that someone might tell you what they think is a funny anecdote about a wild night out but that sounds more like a description of alcoholism? It's fair to say that the source material, a best-selling 2011 novel written by Ernest Cline, does not. The reference-packed book is devoid of any subtext that might make its geek fantasy, in which a young man saves the (virtual) day with his incredibly thorough knowledge of pop culture, go down less smoothly. But the new movie adaptation of Ready Player One, directed by Steven Spielberg from a screenplay Cline wrote with Zak Penn, shows occasional glimpses of self-awareness that feel like the equivalent of watching someone's fixed smile slipping.

Ready Player One takes place in a near future where everyone is burying themselves in entertainment while things go to hell around them — not that there's anything wrong with that. Wade Watts (played by Tye Sheridan), the film's undistinguished protagonist, lives with his aunt and her latest lousy boyfriend, and spends his days in an immersive virtual simulation called the OASIS, where he tries to solve the mysteries of a quest laid out by late OASIS founder James Halliday (Mark Rylance). Wade and fellow "Gunters" like Art3mis (Olivia Cooke) and Aech (Lena Waithe) are obsessed with figuring out the secrets behind Halliday's game, which, Willy Wonka–like, will grant the winner control of the OASIS and Halliday’s company, Gregarious Games. (Morale at the company must be crushingly low as they wait to find out which internet rando is going to be their new boss.) Their larger-than-life online adventures include an impossible race through a fantasy New York and a battle that enlists the Iron Giant, Mechagodzilla, and dozens of other familiar fictional figures. And yet it all feels like a nightmare recounted with a cheery lilt.

There are actually glimpses of that bleakness in the terror on Art3mis's face as she's dragged off to the same corporate indentured servitude in which her father died, trying to work off debt he could never clear. It's also in the opening shot, in which the camera pans down along the windows of the vertical trailer park where Wade lives, showing us a row of people escaping from desperate poverty into the online world where the film also spends most of its time. The darkness is there, but it's never there too long, as if Spielberg, who helped shaped the modern-day blockbuster, were hesitant about losing his target audience with anything that might suggest there are any complications to their rollicking, nostalgia-fueled adventure. "This is not a film that we made; this is, I promise you, a movie," he told the cheering crowd at Ready Player One's SXSW premiere, distinguishing it from the mostly serious work he's been doing for the last few years. And a movie, apparently, isn't supposed to push too hard — it's just supposed to entertain.

When the novel Ready Player One was published, it drew a lot of attention for the fact that it was, essentially, a compendium of pop culture references related to what Halliday (standing in, tastewise, for his author, Cline) loved most. It was a 101-proof shot of nostalgia as served up by a former '80s teenage boy from Ohio (which, layered over with a dystopian filter, is where the movie takes place) — a boy who liked Rush and Monty Python, WarGames and arcade games, and who dreamed up a sci-fi future in which everyone would care about his faves as much as he did — because, if they wanted to win, they would have to.

A lot of the pop culture references in the adaptation have been updated, improved, added to, or made more cinematic, including a sequence in which The Shining gets turned into a survival horror experience in a way that's both blasphemous and easily the most memorable part of the movie. But onscreen, even though familiar characters (Duke Nukem! Gundam! Chucky!) fill the frame, franchises cross, and the legal fees to clear everything must have been astronomical, Ready Player One doesn't really feel like it’s about nostalgia. Instead, it seems more concerned with escapism, and how much its characters use pop culture as a womb to shelter them from the ugly realities they've accepted from the world outside. It’s not about looking back so much as looking away.

In Ready Player One, everything IRL is falling apart, and all Wade cares about is saving his high-end MMORPG from the rival corporation, IOI, which intends to put ads everywhere and set tiered pricing for access. At a certain point, Art3mis even calls Wade out for his lack of engagement, yelling, "You don't live in the real world! You live inside this illusion!" But he hardly seems to be alone in that — Art3mis and her fellow rebellion members, who are intent on taking down IOI for political reasons, seem to be few and far between.

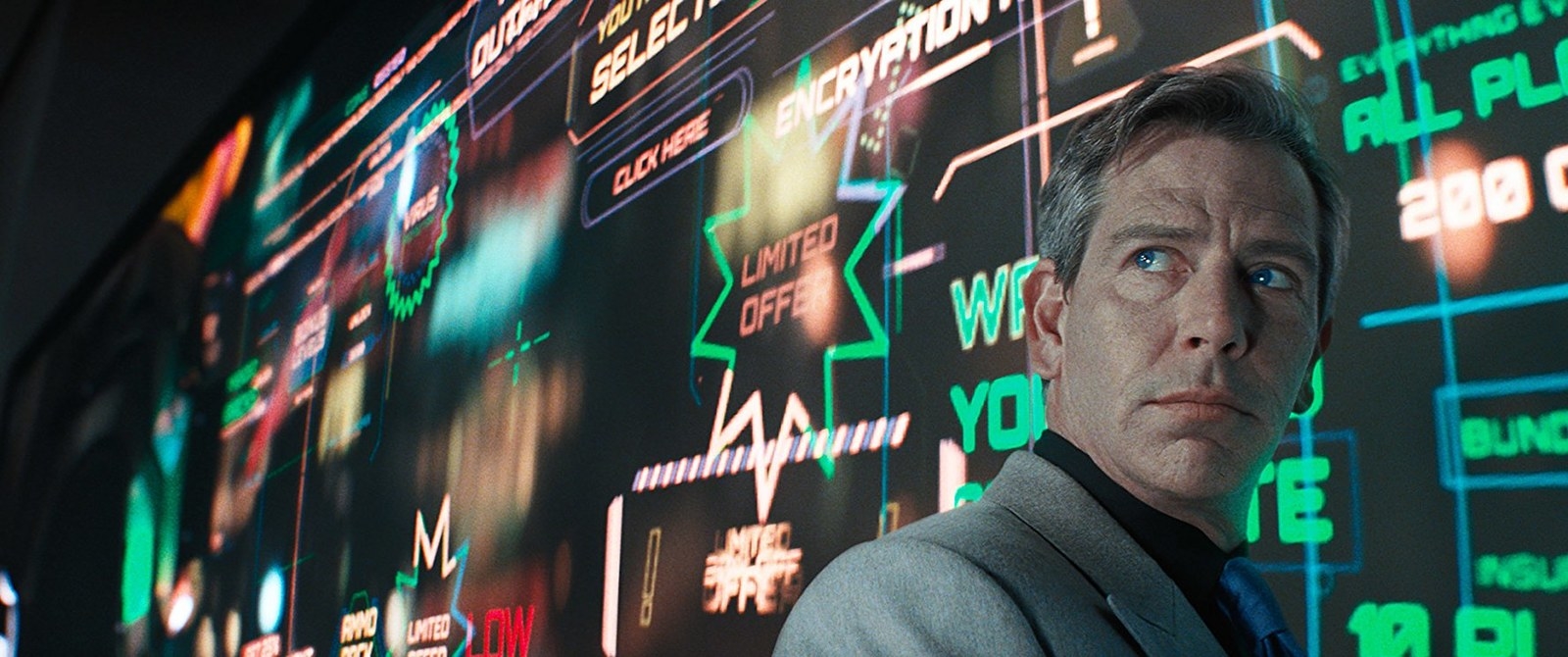

Everyone else in Ready Player One appears to have given up on the real world, to have accepted that its problems can't be fixed and that the best you can do is accept your fate and try to forget reality. IOI's villainous CEO Nolan Sorrento (Ben Mendelsohn), the movie's main antagonist, gets mocked for his technical ineptitude and his fake geek posturing. But given that legitimacy, in this context, involves checking out of the real world to bury yourself in decades-old pop culture while corporations take control, he seems to be getting the last laugh.

The particular breed of fandom that Ready Player One was written as an ode to, is, in some ways, just as much a relic of the past as some of the references that get dredged up and put onscreen. It's an idea of fandom as primarily a refuge for awkward white men who felt uncertain around mainstream society, generally, and women, specifically. Wade acquires a collection of non-hetero-white-male allies along the way, but the story is still his, and it's paralleled with revelations about Halliday's own retreat from reality and subsequent regret.

Fandom, in Ready Player One's conception, may be sincere, but it's also diametrically opposed to getting a life.

Fandom, in Ready Player One's conception, may be sincere, but it's also diametrically opposed to getting a life. It's only after getting a girlfriend that Wade feels comfortable pulling away from the OASIS (and, in the movie, cutting off worldwide access to it twice a week). It's fandom as a sanctuary, but also a gated kingdom of the sort symbolized by the likes of Cline's longtime friend (and character in his screenplay for 2009's Fanboys) Harry Knowles, the Ain't It Cool News founder who became an early web icon of insular geekdom, and whose public downfall came last fall when he was accused of sexual assault and stepped down from the community he built.

That sort of fandom doesn't reflect the ways in which geekiness has evolved and been pried open, or the ways in which it is currently far more widespread and diverse and, at this point, culturally dominant than the stale vision of Ready Player One. This new understanding of fandom is also, unlike in Ready Player One, socially and politically engaged in a way that does not match Wade's complacent consumption of media. More than ever, mass entertainment is fought over for how it reflects, or doesn't reflect, the real world. References to Harry Potter and Black Panther become part of the language of political resistance and pop up on signs at protests. The relationship between politics and art may be incredibly messy, but it's also vivid and unignorable.

And so while Ready Player One is a kind of accidental horror movie, a big, escapist entertainment vehicle about how big, escapist entertainment vehicles are drugs with which the masses sedate themselves, it also feels out of touch with the times. It is, despite Spielberg's claims, neither a purehearted popcorn flick nor a Paul Verhoevenesque subversion, but something uneasily in between, cowed by the idea of the fanboy demographic it seems to be aimed at. But that's also why, alongside Spielberg’s idea that “movies” and “films” are two different things that don't intersect, it feels so wanly out-of-date. Wade ultimately has to be anointed with sex, power, and wealth in order for him to feel okay about coming out of his comfort zone and engaging with the real world. Let him stay there. The rest of us are already here. ●