It started with a noise complaint. Don Hansbury, who is 78 years old and white, went to the doorway of his home in Troy, New York, that August night in 2013 to see what was going on. “Cop was talking to a guy with loud music playing from his car, colored guy,” he said. “I knew something was gonna happen.”

The cop was talking to Hansbury’s across-the-street neighbor, Sam Ratley, who is 39 years old and black. Soon, Hansbury heard “some kind of scuffle,” and then police cars filled the block. After a few minutes, Ratley and two other black men were led away in handcuffs. Though Hansbury didn’t see what happened, he said, “I just knew that guy beat up the cop.”

That was the story in the police report, conveyed in the local newspaper the next day. According to police, Ratley refused to turn his music down and when Officers Dominick Comitale and Brandon Cipperly began to handcuff him, a crowd gathered and attacked the cops. Ratley and two others were charged with resisting arrest and assaulting a police officer.

Jurors didn’t buy that story. They acquitted Ratley, who testified that Officer Comitale had pulled up outside his home and immediately begun cursing at Ratley as he sat on his porch with some friends and relatives. When the group got up to go inside, Ratley said, the officer shoved him against the building and kneed him in the face and chest. Ratley sued the department and received a $60,000 settlement last year.

It was a familiar story in Troy — where, over the last six years, at least seven black residents have been acquitted of resisting arrest and then paid by the city over claims of police brutality — and evidence of a nationwide trend driven by demographic shifts shaking the country. As black and brown people leave major cities to raise families in areas that were once predominantly white, they’re encountering police departments that are slow to reflect those population shifts and all too eager to placate longtime white residents who equate change with rising crime. To those white residents, the officers serve as a final line of defense against the outsiders marching onto their land, uniformed allies paid to protect them from the dangers they feel closing in around them.

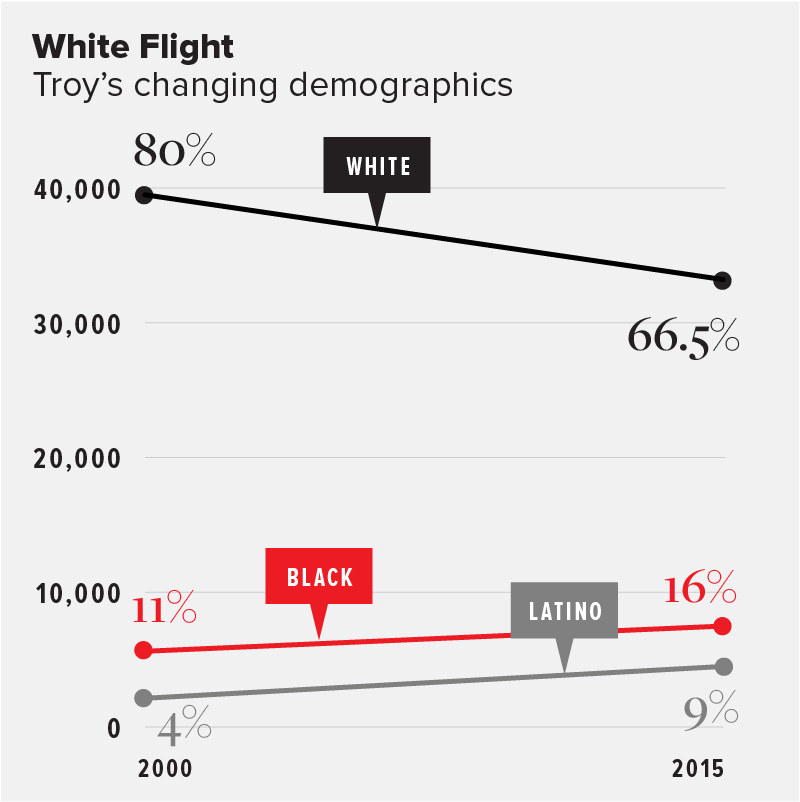

A Rust Belt city of 50,000 about 150 miles north of Manhattan, Troy, 92% white in 1980, is barely two-thirds white today, a transformation sweeping suburbs and small cities as a result of old barriers of enforced segregation dissolving, opening new lanes of migration. From 2000 to 2010, the black population declined by a total of nearly 300,000 people in the US’s four biggest cities: New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Houston; Atlanta’s black population dropped by 30,000. This dispersal, combined with a fast-growing Latino population, has turned formerly all-white places into merely majority white places — and formerly majority white places into places where whites are outnumbered by people of color: Of the US’s 100 biggest metropolitan areas in 1990, 25 cities and 5 suburbs were majority black, Latino, and Asian; by 2010, that had increased to 58 cities and 16 suburbs.

From 2000 to 2010, the number of black residents in Troy grew by 46%. Yet the police force remains 95% white, with just four black and two Latino officers on a staff of 120 — a common proportion in these quickly changing cities. In Balch Springs, Texas, where last month a white police officer responding to a complaint about underage drinking shot and killed 15-year-old Jordan Edwards, the police force remains nearly all white even as the city’s white population has drastically declined, from 63% in 2000 to 51% in 2010 and likely even lower today.

The result is a combustible mix: a white population anxious about its new black neighbors, and a white police force unprepared and ill-equipped to handle the thickening racial tensions.

“It’s white protectionism,” said Seth Stoughton, a former police officer in Florida who is now a law professor at the University of South Carolina. “When that element of otherness invades our community, it’s very easy to react as if we are being threatened, and to be fearful. And we react by calling the police.”

In 2011, the city of Antioch, California, where the white population declined from 65% in 2000 to 49% in 2010, settled a class-action lawsuit filed by black residents who accused the police department of racial discrimination. In 2016, locals filed a lawsuit against 13 suburban counties outside St. Louis, whose combined white population dropped by more than 30% from 2000 to 2010, accusing the towns of “extorting money” from black people through discriminatory traffic stops.

The most famous recent example of the consequences of white protectionism is Ferguson, Missouri, where the population transformed from 99% white in 1970 to less than 30% in 2010. The Justice Department, investigating the city after the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown in 2014, discovered that 93% of those arrested over a two-year-stretch were black. The police department that year was 94% white.

Within the last decade, the Justice Department found evidence of racial bias by law enforcement in at least eight other cities and counties with rapidly growing minority populations in New York, Connecticut, North Carolina, and Mississippi. Similar investigations seem unlikely under Attorney General Jeff Sessions, who has made clear his belief that the DOJ should not aggressively push for changes in local law enforcement agencies.

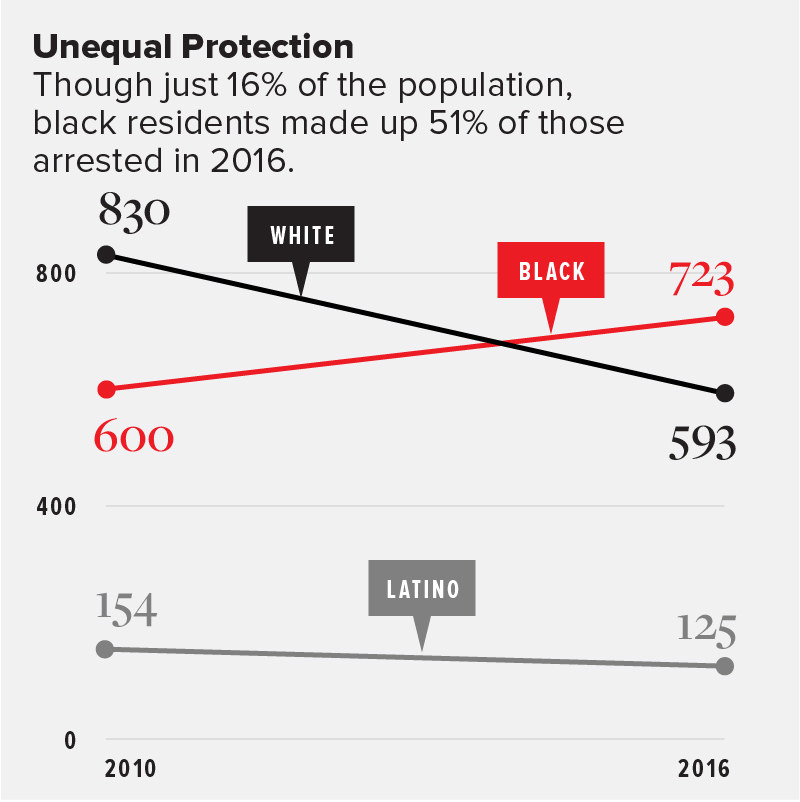

In Troy, black residents say police harassment and racial profiling are an everyday fact of life — and seem to be increasing. Black people, though just 16% of the population, made up 39% of those arrested in 2010, then 51% in 2016, according to a BuzzFeed News analysis of the department's arrest records. In 2016, 90% of minors arrested for marijuana possession were black, up from 56% in 2010.

“It’s a constant picking on the people in those communities,” said Bob Fitzgerald, a longtime Troy police officer who served as union boss for 12 years before retiring in 2014. “That was all we knew. If you were to see a black male on the street corner, or a group, unfortunately the thought there was ‘Oh my god, somebody must be dealing drugs.’ They were like a magnet to the police department.”

To many black residents, the police department seems to be passing along a message from their white neighbors: You’re not welcome here.

Just like the millions of white people who migrated to the suburbs generations ago, many of Troy’s black residents arrived in recent years to escape the big cities.

Jahnasia Jordan, a 21-year-old convenience store worker, moved from New York City because “it’s cheaper.” Michael Hailing, a 59-year-old handyman who grew up in Brooklyn, came to Troy because there was “more space.” Jameer Barker, a 23-year-old truck loader, left New York City with his mother five years ago because “it’s more quiet here.” Low-income families arrived after rising rent prices pushed them out of big cities. Upwardly mobile families arrived in search of affordable houses with garages and sprawling backyards to raise their kids in.

After the manufacturing industries began to decline decades ago, Troy’s population dipped from its peak of 77,000, where it had hovered from the 1910s to the 1950s. But walk around Troy today and you'll see little resemblance to the hollowed-out old boomtowns that dot the Midwest and Northeast. There are few vacant storefronts along the main streets, where young people pop in and out of restaurants serving Asian fusion cuisine and bars with craft beer on draft. The county’s unemployment rate is below the state average. This is not a place dripping with despair. The signposts that people tend to associate with social turmoil — blight, filth, visible disorder — are absent, making all the more incongruous any assumptions that this is a dangerous place.

“Recent outcries about the ‘rising crime rate’ in Troy have been grossly exaggerated.”

Troy adapted to the US manufacturing decline better than most Rust Belt towns. Two hospitals and four colleges offered job opportunities that drew many of the newcomers of the last two decades. As old black families built roots and new ones moved in, the city’s racial composition began to shift, its once-small black community expanding past previous boundaries, slowly integrating the city in the 1990s and 2000s.

While the number of Troy’s white residents decreased from 2000 to 2010, its overall population rose slightly, thanks to the influx of black and Latino people — the city’s first decade of population growth since the 1940s. These newcomers arrived to find a climate of resistance.

David Brewington, a black 18-year-old student from Albany, moved to Troy in January. Over his first three months in town, Brewington was stopped by police “once or twice a week,” he said. “We just be walking and they pull us over for no reason.”

Still, he added, “I guess I’m lucky it hasn’t been worse.”

The allegations of police abuse against black residents tend to hit the same plot points: a stop for a low-level infraction; an interaction that escalates; use of force by officers; a charge of resisting arrest, dismissed by prosecutors or acquitted at trial; and then a lawsuit settlement with the city that allows officers to deny the allegations of misconduct.

In 2010, two officers beat James Foley with batons after he began filming them as they beat another man, Shakim Miller, at a nightclub. In 2011, Officers Isaac Bertos, Russell Clements, Justin Ashe, and four others beat and tased Lamont Johnson during a traffic stop while his girlfriend and two small children sat inside the car down the street from their house. That same year, Officers Comitale and Ashe beat and pepper sprayed John Larkins while he was at a hospital waiting for a doctor to stitch up a cut on his aunt’s arm. In 2012, Bertos stopped Archie Davis, a college student, and three of his friends for jaywalking, and then, along with Comitale and Clements, punched and tased Davis after he called his father on his cell phone. In 2013, Bertos tased Robert Washington after stopping him for holding an open container of alcohol. Comitale and Bertos, each involved in at least three of these cases, and Clements and Ashe, each involved in at least two, all remain on the force.

In these cases and others, black residents claimed that officers came at them aggressively, immediately escalated the situation with shouts and accusations, and responded with violence to anything less than deference. (Troy Police Chief John Tedesco and several officers mentioned in this story declined interview requests.)

One 15-year-old boy, who requested anonymity, described an afternoon earlier this year when police officers stopped him while he was riding his dirt bike a few blocks from his house.

“When they drew a gun on me, I thought I was about to die,” he said, adding that the officers searched him and then let him go. “They racist as fuck.”

BuzzFeed News spoke to dozens of Troy residents: While nearly every black resident interviewed said that the city’s biggest problem is police harassment, many white residents said that the city’s biggest problem is rising crime.

In fact, the city’s crime rate in 2016 was its lowest in at least a decade. This false perception of danger among white residents was so pervasive that in 2013, Chief Tedesco penned an op-ed for the Troy Record to address the “confounded interpretation of the true statistics,” writing, “Recent outcries about the ‘rising crime rate’ in Troy have been grossly exaggerated.”

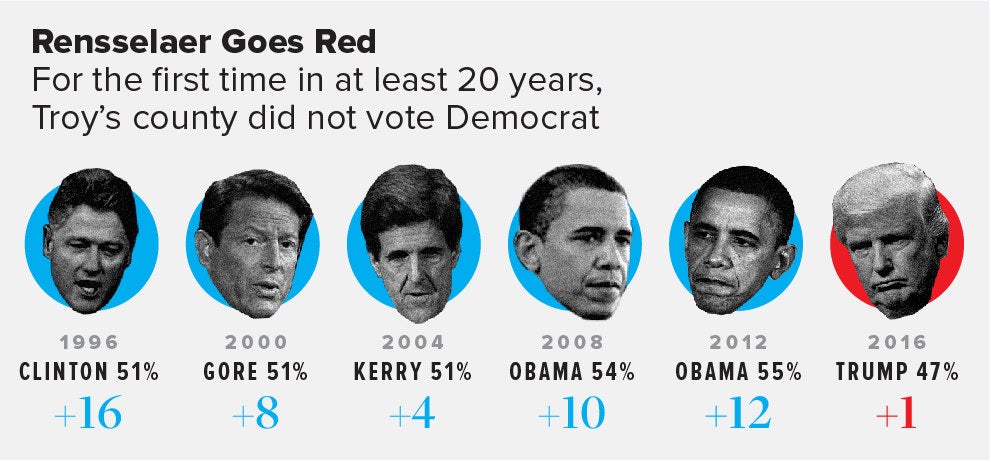

The white fear simmering in Troy is a familiar one. Residents in changing white cities all over the country, but especially across the Rust Belt, seemed to express their anxieties in the 2016 presidential election, turning to a candidate whose message targeted white people nostalgic for days long gone, before the “American carnage” Donald Trump described in his inaugural address. It's a vision of the country that calls on police to suppress the forces that threaten the old order. “Our country needs more law enforcement,” the administration states on the White House website. “Our job is not to make life more comfortable for the rioter, the looter, or the violent disrupter.”

The country is not in a state of heightened danger: 2015 had the third-lowest violent-crime rate of any year since 1970, according to FBI statistics. (Complete 2016 data is not yet available.) Rather, the most visible threats to the old order are racial.

Harvard political scientist Ryan Enos found that white people who had previously voted for Barack Obama were more likely to vote for Trump if they lived in cities with fast-growing Latino populations. In places like Macomb County, Michigan; Kenosha County, Wisconsin; Porter County, Indiana; and Northampton County, Pennsylvania — which all flipped by at least 10% from the Democrat presidential candidate in 2012 to the Republican in 2016 — black and Latino residents doubled in number from 2000 to 2010, expanding to more than 10% of their county’s population.

Indeed, the residents of Rensselaer County, a third of whom live in Troy, voted for the Democratic candidate in every election from 1988 to 2012, when they elected Obama by a 12% margin. Last November, they swung to Trump.

Don Hansbury’s grandparents moved their family upstate from New York City in the 1920s, when Troy was a booming factory town. Wedged along a seven-mile stretch of the Hudson River’s east bank, the city was a hub for shipping, textile production, and ironworks. Hansbury’s grandfather worked in maintenance.

The plentiful jobs drew people from all over, including black Southerners hoping to escape Jim Crow. One enterprising local pastor recruited new residents from South Carolina, sending buses to bring them up and helping them find homes once they arrived. For years, though, the city’s black community remained small. “There was a clear distinction between the white and the black parts of town,” said Willie Bacote, a pastor who grew up in South Carolina before moving to Troy. “You couldn’t go past 101st Street.”

Sitting on his stoop waiting for the mail carrier on a cold morning in March, Hansbury spoke wistfully of his grandfather’s days and of the years that followed, when his widowed mother worked at a nursing home and he began his career as a mechanic in the late 1950s.

It’s sentiment commonly expressed in cities across the Rust Belt and Coal Country, where white people long for a time when manufacturing drove the economy and the grip of white dominance was tight.

“It’s a different place for raising your kids,” said Greg Lanni, a white 57-year-old middle school PE teacher who grew up in Troy. “It used to be more of a safe place to raise your kids and it changed to a, I don’t want to say urban" — he paused — “but a lot of things have changed.”

Another white resident, Frank Spatafora, a chef in his fifties, said, “Certain areas have gotten worse — crime, drugs.” Don Osgood, a white 39-year-old contractor who has spent his life in Troy, said he hoped to leave “someday.” “I’d rather live out in the country,” he said. “This place is fuckin’ dangerous, man.”

Hansbury said the city began to change soon after he bought his house in 1983. Within a few years, he recalled, he began to see “a lot of colored people on this block.”

Many of the newcomers were good people, he said, but some brought trouble. “You can’t have music blaring like that,” he said. “You can’t have people sitting on the porch that’s not from the house.”

He became concerned about his safety. He joined a neighborhood-watch-type program that encouraged him to check in at the police station every month and report anything suspicious he observed. He has been satisfied with the department's response.

“When you have a problem, you call them and they come right away,” he said. “We’ve got quite a police force. When they come, you see like 13, 14, 15 police cars and they all block the whole road up.”

The leaders and veterans of the Troy Police Department began their careers at a time when aggressive policies were standard across the country. When Bob Fitzgerald graduated the police academy in 1990, “they released us into the community and said there was a war on drugs,” he said. “So you were dropping in thinking, We’re at war here.” That mindset, he said, forms the basis of the policing culture that remains in place today.

The department does not have arrest quotas, but, like many departments, it rewards productivity, and arrests are the simplest measure of productivity. “It could help in a promotion,” Fitzgerald said. “You don’t wanna be known as a slacker. And where are you gonna get your numbers from? Where are you gonna go? You go to the inner city.” The reasoning was based on officers’ perceptions of the nature of crime: “Without getting real racial, most drug users are white, most drug dealers are black,” Fitzgerald said. “If they’re selling drugs inside the house, it’s probably a white guy, whereas the black dealer is in the street.”

And so that’s who officers look for and stop.

According to Fitzgerald, it’s common for officers to use low-level infractions as a pretense to arrest and search people — fishing expeditions for drugs and guns. In 2005, the Troy Record reported that, over a three-year span, Troy officers arrested 274 people for jaywalking and 88 people for not having lights or a bell on their bike; more than 75% of them were black or Latino. The City Council responded to the news by passing a law that required officers to instead issue a ticket for those infractions as long as a person had ID. But in the years since, the city has not kept track of whether officers have pursued these infractions evenly. In response to a public records request, a spokesperson for the city said the department did not have records for citations and arrests for traffic offenses from 2006 to 2016.

Every excessive force lawsuit filed against Troy police by black residents within the last decade stemmed from encounters over low-level infractions. Why do they escalate? To Fitzgerald, the answer lies in the city’s demographic shift.

“When you hire people to become officers, they’re trained to enforce the law, but they’re not trained on how to handle the cultural differences they’re gonna see,” Fitzgerald said, citing the longtime distrust of police that fueled the Black Lives Matter movement.

“When you hire people to become officers, they’re trained to enforce the law, but they’re not trained on how to handle the cultural differences they’re gonna see.”

It’s the same dynamic Ron Hampton saw among fellow patrol officers in Washington DC, during the later years of the white flight era, when the police department was far less black than the city. “A lot of the guys on the force had an ignorance because they had not lived or went to school with any African-Americans,” said Hampton, who is black and worked as an officer for more than 20 years. “Yet they were expected to work in those communities, and that created conflict.”

A diverse department does not solve all problems — ask black and Latino residents of Chicago and New York City. But, several black retired cops said, the first step toward improving relations between police and black residents is hiring officers who can at least relate to being black in America. According to former union boss Fitzgerald, the Troy Police Department made no such effort during his years in the department from 1990 to 2014.

“For officers who might not have had much exposure to people of color, it’s important to get an understanding of the dynamic of why we fear police in our communities,” said Jeffrey Fletcher, who is black and was a cop in New Haven for more than 20 years.

This disconnect between white officers and black residents in Troy was never clearer than in early 2014, when a night of brutality sparked the biggest protests the city had seen in decades, if not longer.

At around 2:45 a.m. on a Saturday morning in January 2014, police responded to a call about a fight between a bouncer and a patron at Kokopellis, a hookah lounge downtown.

By the time the officers arrived, the scene had calmed. The bar’s owner had called it a night and turned on the lights. People were finishing their drinks, lining up at the coat check, and filing out. Then things exploded. Surveillance footage showed that the chaos began after an officer stormed over to a black man standing in the coat check line and got right in his face, chastising him for saying something disrespectful — a chain of events later detailed at a City Council meeting. When another officer placed a hand on the black man’s chest and the man swiped it away, more officers converged, grabbing people and throwing them around. Within seconds, officers were beating black men with batons. People rushed out of the bar. Somebody sprayed a fire extinguisher. Somebody else threw a trash can at a police car parked outside.

When the beatings stopped and the fire extinguisher residue cleared, one injured black man was motionless on the ground and others were dragged out and arrested.

The footage hit the local news, and outrage spread across the city. Scores of protesters marched. Activists spoke out at rallies about the pattern of police brutality. A few public officials called for an investigation into the officers’ actions. A City Council meeting convened to address the incident drew more than 400 people, so many that it had to be held at a church because there was not enough space in City Hall.

The public comment portion of the meeting lasted more than an hour, as residents, one after the other, described their own experiences of police harassment. One of the last to speak was Barry Glick, the 68-year-old Kokopellis owner who had lived just outside Troy for three decades.

“The police entered my building looking for a fight,” said Glick, who is white. “The city of Troy has demonstrated that it is not a very welcoming place.”

The audience gave him a standing ovation.

“The city of Troy has demonstrated that it is not a very welcoming place.”

But the people in that church did not represent the whole city. The protests brought a backlash. Many believed the police department had rightfully stamped out the sort of disorder they worried about. Residents wrote letters to the editor defending the officers. One bar owner started a Facebook page in support of local law enforcement. The owner of a hardware store posted a sign stating that his establishment backed the police. Other residents praised the department at City Council meetings. Willie Bacote, the black pastor who led the protests, said that he received death threats and began to travel with bodyguards.

The mayor and the police chief ultimately announced that the officers had acted appropriately at Kokopellis. No major reforms were implemented. A civilian review board, created to appease protesters, “fell into disuse” within a few months because the mayor “didn’t appoint enough people and they just stopped meeting,” said Council Member Bob Doherty, chair of the body’s public safety committee from 2014 to 2016.

“They really haven’t tried to change their policing style or philosophy,” said Alice Green, director of the Center for Law and Justice, which is based in nearby Albany. “I don’t see any evidence that they’ve done anything since 2014 to do that.”

A year after the incident, Kokopellis shut down.

Even some of the department’s harshest critics have expressed support for Police Chief John Tedesco, who built his reputation as the first captain of the department’s community policing unit when it was formed in 1998. At every attempt at reform, they said, the union got in his way.

“The man tried in every form and fashion, but it didn’t seem like he had the backup to do what he wanted,” said Bacote, who called for Tedesco’s firing after the Kokopellis incident.

Among the proposals stifled by the union were Tedesco’s efforts to put cameras in every police car and bring in the FBI to investigate the internal affairs unit.

Recently, though, the union has seemed to make strides toward building trust with the city’s black residents. Today, the union boss is Detective Aaron Collington, one of four black cops on the force. He was one of two when he first joined. He rose to detective, took over the union, and on Martin Luther King Jr. Day this year, he spoke to black residents about what rights they have if police stop them. “It’s been a roller-coaster ride,” Collington, who grew up in Troy, told BuzzFeed News. “The perception is the community and the police are at odds all the time, but I just don’t see it that way.”

Residents have pinned their hopes on the department reforming from the inside. In 2014, Bacote and other community leaders called on the Department of Justice to investigate Troy police. But now, under the new administration, they doubt help will arrive from Washington. In early April, Attorney General Sessions announced that his office would review all police consent decrees — legally binding reforms — it inherited from the Obama years.

Residents have pinned their hopes on the department reforming from the inside.

What has not changed is that the uprisings in Ferguson, Baltimore, and elsewhere still loom over every mayor, police chief, and district attorney, who have seen peers lose jobs in the aftermath of high-profile police misconduct. Facing this reality, police officials in many cities have made fresh efforts to build trust with black communities.

This new mindset was clear in the week following the fatal shooting of Jordan Edwards in Balch Springs, Texas. Less than 48 hours after Jordan’s death, Police Chief Jonathan Haber announced that video footage contradicted Officer Oliver’s statements. The next day, Haber fired Oliver. Three days later, Dallas County District Attorney Faith Johnson filed murder charges against Oliver.

But unlike in Balch Springs, Ferguson, Baton Rouge, Milwaukee, Baltimore, and Chicago, black residents are still a slim minority in Troy and in the growing number of other diversifying cities where police misconduct affects communities without the numbers to turn an election or flood the streets. Instead, police in these places face pressures levied by anxious white constituents who expect officers to hold the line against the unwanted elements invading their communities.

In these post-Ferguson years, it has been fatalities that ignite the outrage and attention that spur change, but the tensions in Troy reflect a wider issue: the constant drumbeat of harassment and low-impact brutality punishing black and brown communities, a growing collection of small indignities and injustices. No single one is shocking enough to make national headlines, yet together they make up the heart of the distrust cops must overcome. Places like Troy are the true test of post-Ferguson progress.

Hansbury remembered when Sam Ratley moved onto his block in 2009. He eyed Ratley and his family with suspicion. “I know the kind of people who live up on that side,” Hansbury said. “Drugs and prostitutes, things like that.”

Ratley, who had arrived from Brooklyn, worked in a warehouse and had no criminal record. To Ratley, the block he’d found in Troy was an affordable, clean, quiet place to raise a family. But he felt differently after the incident in 2013.

When Ratley and his family moved to a different neighborhood, Hansbury was glad to see them go.

“They all got put out,” Hansbury said. “The cops cleared it up.” ●