The crowd was mostly white when the high school quarterback knelt during the national anthem, his silent protest playing out on a cool desert night. It was the second time that V.A., the 17-year-old star player from San Pasqual Valley High in Winterhaven, California, had taken a knee to protest racial injustice, an act inspired by the NFL players who’d sat, knelt, or raised fists that fall.

But the first time had been on his home field in front of supportive classmates and parents, most of them Latino or, like V.A., Native American. This time, he was 250 miles from home, in Mayer, Arizona, before a high school whose student body was 78% white.

The crowd was silent as the music blared, and the game went on as normal, with Mayer winning 78–8. The repercussions came later.

After the Oct. 6 game, five or six Mayer High students approached a pair of San Pasqual Valley cheerleaders and V.A.’s mother, who is the cheerleading coach, outside the visitors’ locker room. According to her testimony, the Mayer students said they were looking for the boy who had knelt so they could “pull him onto our field and force him to stand.”

“Go back across the border,” one said, according to the testimony.

“We stole your land.”

“This is America.”

Other students, and some adults, joined in the taunts, she said, and some hurled water on the San Pasqual Valley cheerleaders, players, and coaches as they lined up to board their bus.

The San Pasqual Valley High Warriors (in blue and yellow) at a home game in Sept. 2017.

Six days later, the San Pasqual Valley school district superintendent, Rauna Fox, announced a new policy: Anyone who didn’t stand for the national anthem would be kicked off the team. V.A., who requested anonymity for fear of retaliation, was stunned.

Hoping to continue his protest through basketball season in the winter and baseball in the spring, the teen and his family have sued the school district, alleging a violation of his constitutional right to free speech — the latest chapter in the movement sparked by former San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick in August 2016.

What started as a demonstration among professional athletes against racism and police brutality has spread to high school athletes, including cheerleaders, and ignited debate over students’ First Amendment rights. Half a century after the US Supreme Court ruled that an Iowa high school had illegally barred students from protesting the war in Vietnam, V.A.’s lawsuit could set new precedents on free speech protections for public school students.

“The people who are trying to stifle speech should not be able to do so by shouting down those who protest or threatening them.”

“The people who are trying to stifle speech should not be able to do so by shouting down those who protest or threatening them,” said Ira Gottlieb, the attorney representing V.A.’s family. “We need greater protections than that.”

Long before judges got involved, school administrators and youth coaches across the country decided on whether to allow the protests, which spread across the country through the fall as students followed the lead of the more than 200 professional football players who knelt or sat this season.

Since last summer, at least five high schools and colleges have banned anthem protests, and at least four students have been disciplined, including being suspended and kicked off sports teams. On the other end of the spectrum, the DeKalb County School District in Georgia defended its students’ right to protest after receiving a complaint about high school softball players kneeling during the anthem.

The backlash over the protests has turned the country’s most popular sport into its most polarizing. A survey by the polling firm Morning Consult found that the percentage of Donald Trump voters who viewed the NFL unfavorably jumped from around 25% in early September — the same rate as Hillary Clinton voters — to more than 60% by the end of the month. Clinton voters stayed about the same.

“You might as well be stomping on the flag.”

Some fans called for a boycott of the league. So many people ended their NFL Sunday Ticket subscriptions, a cable package that offers every game, that DirecTV refunded those who cited the player protests as their reason for canceling, the Wall Street Journal reported. One Florida restaurant hosted a party to burn NFL merchandise, offering free food to anyone who tossed items into fiery barrels set up on the property. A Denver Ford dealership, the Air Academy Federal Credit Union, and the telecommunications company CenturyLink ended endorsement deals with protesting players.

“You might as well be stomping on the flag,” said Bill Rutledge, a 69-year-old retired car salesperson, Vietnam war veteran, and former Cleveland Browns season ticket holder living in Florida. “I hope they realize the pain they have caused those of us that were fans but are soldiers first. They have been stepping on our hearts and souls.”

Administrators in the San Pasqual Valley school district have tried to avoid confronting the issue. On Oct. 12, six days after the trip to Mayer, the football team played its last game of the season. On orders of the school district — and for the first time any of the seniors attending could remember — the national anthem was not played before the game.

The outrage over the protests has given Republicans a new issue to rally around.

Within days of the mass NFL player protest in September, the Republican National Committee sent out fundraising emails mentioning the national anthem, and Trump’s campaign gave out “I Stand for the Flag” stickers in exchange for donations of at least $5. In October, Vice President Mike Pence announced on Twitter that he was walking out of an NFL game because of the protests, and in the months since, the issue has been a common talking point on GOP campaign trails. In December, a state legislator in Louisiana proposed that the state end tax breaks granted to the New Orleans Saints because some of the team’s players had knelt.

In January, Trump retweeted a photo of a military cemetery, writing, “So beautiful….Show this picture to the NFL players who still kneel!"

In January, Trump retweeted a photo of a military cemetery, writing, “Show this picture to the NFL players who still kneel!”

Misleading or false information from a range of websites, including Breitbart.com, litters the Facebook timelines of anti-protest boycotters and has fueled their anger at the kneeling players. The headlines run from accusations (“Kaepernick Ignores Starving Children”) to outright lies (“There are 871 convicted felons playing currently in the NFL”). In interviews, two boycotters repeated the conspiracy theory that the Oakland Raiders’ five offensive linemen, who are all black and all protested, intentionally allowed defenders to hit and injure their white quarterback because he didn’t support their stance.

Many of the fake news stories I encountered on the Facebook timelines of anti-protest boycotters were originally shared by the “Standing for America” page, which has more than 290,000 followers, posts several times a day, and promotes merchandise based on the outrage it helps kindle, including $23 shirts and $38 hoodies with an American flag on the front and the message “I proudly stand for the national anthem.” Brian Fish, a 58-year-old in Texas who stopped watching the NFL this season, bought two of those shirts, for him and his brother.

The items come from a company called Freedom Catalog, which also sells mugs celebrating Donald Trump’s electoral victory and sweaters bearing the president’s likeness and the words “Make Christmas Great Again.” “Products are designed by patriots, for patriots,” its website declares, and its Facebook and Instagram pages are filled with posts disparaging Kaepernick and assertions like, “You’re not white/brown/black/yellow. You’re an American. Start acting like it.” One of the most common memes on these pages shows photos of empty stadium seats alongside claims that the player protests had driven away fans.

In truth, it’s hard to say how many people have decided to boycott the NFL because of the player protests. By my own count, on Nov. 12, the Sunday after Veterans Day, at least 800 people wrote Facebook posts about their participation in the anti-protest boycott; nearly all of them were white.

To Scot Peterson, pro football was supposed to provide an escape from the thoughts that discomforted him. In recent years especially, as he sensed fellow Americans growing angrier and a divide in the country widening, the National Football League was like an old friend who’d never changed, the common ground on which everybody could stand together.

“That used to be the reason we all turned on sports,” said Peterson, a 47-year-old salesperson of heating and air conditioning systems, whose credit card bears the logo of his favorite team, the Green Bay Packers. “Although I do follow politics, I like to keep the two separate.”

Many of the boycotters saw the player protests as a troubling manifestation of the disorder they’d sensed spreading across the country in recent years, from the uprising in Ferguson, Missouri, after the police shooting of Michael Brown to the gun violence in Chicago they keep hearing about. They could consume those images on their own terms, but now the disorder had reached a space they believe to be theirs.

“They have pushed their politics in our faces, then rubbed our nose in it,” Mary Snow, a 63-year-old financial manager and Seattle Seahawks fan from Oregon, said of the kneeling players. “An apology would be nice.”

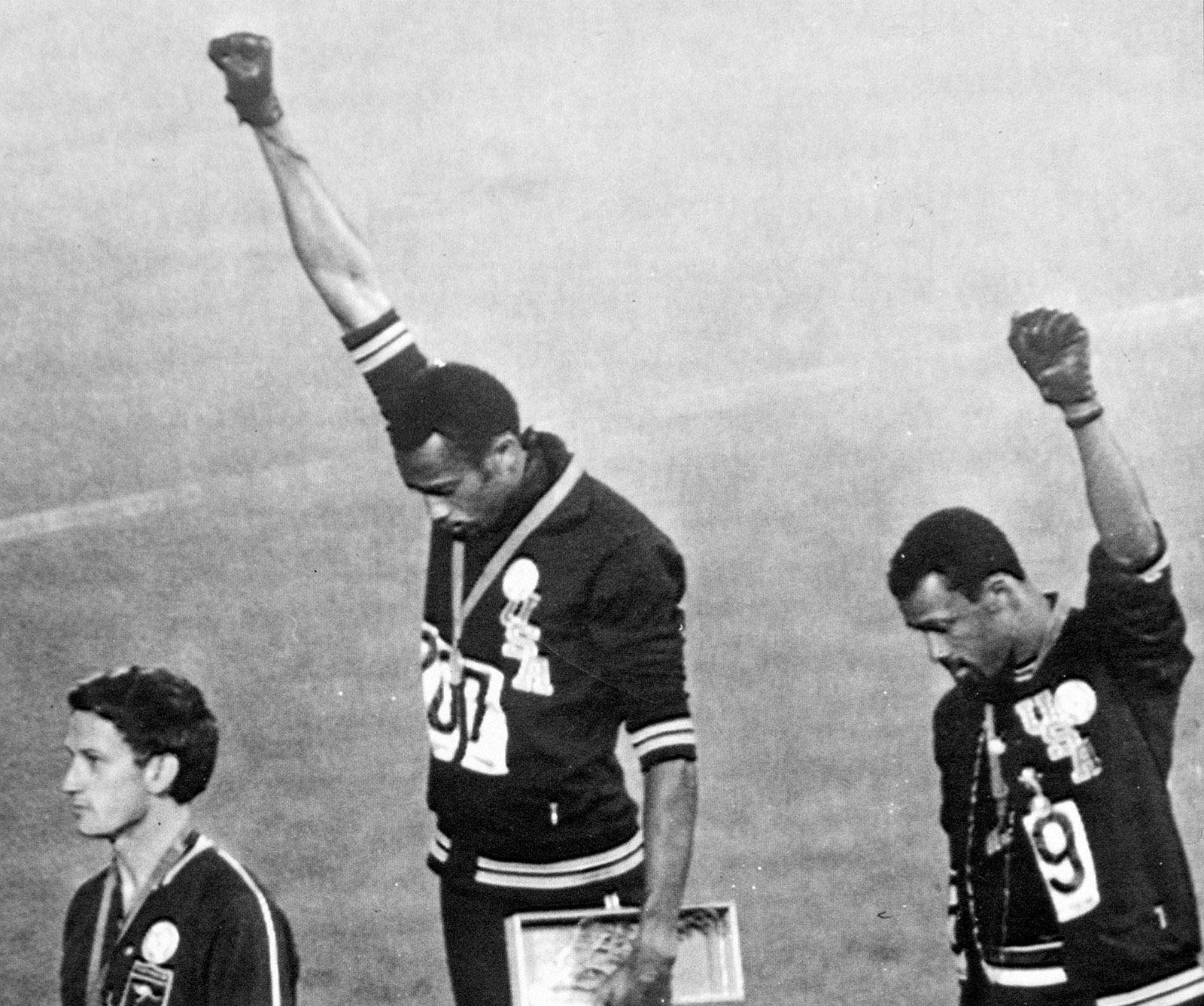

Erick Mann, a 72-year-old Pittsburgh Steelers fan from Texas, remembered the widespread civil rights protests by athletes in the 1960s — Muhammad Ali refusing to fight in Vietnam, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar boycotting the 1968 Olympics, Tommie Smith and John Carlos raising black-gloved fists on the medal podium.

“I didn’t agree with it,” he said. “Am I surprised that this stuff is going on today? No. It pains me.”

San Pasqual Valley High School Principal Darrell Pechtl cited this sentiment when he spoke to V.A. and his mother three days after the game in Mayer, during a Monday morning meeting in which Pechtl told V.A. that his act could be seen by others as “disrespectful,” the principal said in a court statement. The next day, according to the family, Pechtl told V.A. that he would be kicked off any school sports team if he knelt during the anthem.

The day after that, Oct. 11, district superintendent Fox sent a memo to all coaches requiring that they and their players “shall stand and remove hats/helmets and remain standing during the playing or singing of the national anthem.” The new policy explicitly barred “kneeling, sitting or similar forms of political protest during athletic events at any home or away games,” stating that violations “may result in removal from the team and subsequent teams during the school year.” That afternoon, before practice, V.A. and his teammates had to sign a document confirming that they were aware of the new rules. The next day, a letter went out to every student in the district, explaining that the policy was imposed because of a protest that was “not well-received” in Mayer. Pechtl declined interview requests for this story; Fox did not respond to requests for comment.

Though courts have generally sided with protesters, they’ve left open the possibility that if an audience is hostile enough, any speech can be silenced — to prevent violence. This is known as the heckler’s veto.

San Pasqual Valley High School Warriors stand on the sidelines at a football game in Sept. 2017.

San Pasqual Valley doesn’t usually play the national anthem before basketball games, but some schools do. On Nov. 28, before a basketball game at Yuma High School in Arizona, V.A. left the court and stood outside the gym while “The Star-Spangled Banner” played.

In testimony and in a letter to district parents, Fox explained that her decision to suppress the protest was about safety and aimed at avoiding the sort of disturbance that occurred in Mayer.

V.A. continues his protest, no matter what the crowd looks like.

Fifty-two years earlier, school administrators in Des Moines, Iowa, gave a similar explanation for their decision to suspend three students for an act of protest. Fifteen-year-old John Tinker, his 13-year-old sister Mary Beth, and his 16-year-old friend Christopher Eckhardt wore black armbands to school to protest the Vietnam War despite a district policy banning them. The ensuing legal battle eventually reached the US Supreme Court, which ruled in 1969 that the school district had violated the students’ rights by barring them from an act of protest that didn’t interfere with their classmates’ efforts to learn.

Citing this precedent, a federal court in Southern California issued its first ruling in the San Pasqual Valley case on Dec. 21: an order blocking the district’s new rule while the legal process advances toward trial, which is tentatively scheduled for next year. The court noted that V.A.’s lawsuit is “likely to succeed.”

V.A. continues his protest, no matter what the crowd looks like, and even as fewer professional players are still participating. Fewer than 20 NFL players were still kneeling by the end of the regular season, and none did during the playoffs. There’s no telling whether anyone will kneel, sit, or raise a fist at the Super Bowl on Sunday — more than a dozen Eagles and Patriots have protested at some point this season — but NBC has promised to show it if it happens, and kids like V.A. will be watching. ●