My parents rented the movie Gorillas in the Mist for me when I was 10. I had always loved animals, and I devoured nonfiction books on their brains and emotions, from books ranking the intelligence of various dog breeds to the memoirs of famous zookeeper Joan Embery. The movie was an acclaimed biopic about the groundbreaking work of naturalist Dian Fossey and the group of gorillas she studied in Rwanda. My mom thought it would likely become a new favorite.

I sat on our living room couch, sandwiched between my two smart and thoughtful parents, who let me watch just about any movie I was interested in. The film as I remember it slowly and deliberately introduces the gorillas to Fossey and to the viewers. She gives them names. She loves them. They show her their personalities, their emotions, and their commitment to their family. Then, local hunters come and kill the gorillas, intending to sell their hands and heads to tourists. I think it's about halfway through the film, but it's the last scene of the movie I've seen to this day. I remember the scene as violent, painfully realistic, almost macabre. I started screaming at the top of my lungs. Tears streaming down my face, hyperventilating, terrified of my own emotions, unable to comprehend how this could happen, how anyone could do something like this. I was inconsolable. My mom recalls the incident vividly 23 years later, saying it's the most upset she's ever seen me. I look back on the moment as a turning point in my life when I realized that I see animals differently than most people do.

I thought of the gorillas, and my childhood depths of despair, when I was reading about the recent death of Cecil the lion. Cecil was killed by an American dentist in a trophy hunt, a common practice in Africa that results in around 500 lion deaths every year (not to mention elephants, giraffes, and other animals). His death seems to have been technically illegal, specifically because he was lured out of one kind of protected land and into another. Cecil had a name and was beloved (by tourists) on the wildlife preserve he called home. His death has led to tears, calls for change, and countless think pieces. I understand all of this grief. I cried too when I saw the photos of the dentist posing next to such a huge and majestic dead body. Even the poachers in Rwanda had a reason: bringing in money they could share with their families. But this rich American paid for the experience, he did it for fun — how strange and sick he must be.

Although I find Cecil's death disgusting and unnecessary, I share a concern I've seen friends express in different ways over these last couple weeks: Why this? An individual is more than capable of caring about more than one issue or injustice at a time, and many of us do, but Cecil news has dominated the cycle of chatter and outrage for over a week and counting. It's fair to ask why certain victims receive an outpouring of attention while other victims are ignored or worse. If you're publicly mourning Cecil but you aren't moved by the big game trophy hunting that happens everywhere, or the atrocious human rights violations taking place in other countries, or by police officers who shoot unarmed and nonviolent teenagers, it becomes fair to ask: Why now? Why this life?

Two years after I watched Gorillas in the Mist, I declared myself a vegetarian. I'd spent the preceding months pondering the ethical ramifications of meat-eating, reading as much as I could find about animal rights philosophy, and building myself up to the official decision — mostly by getting into arguments with family friends about why eating meat was bad and wrong.

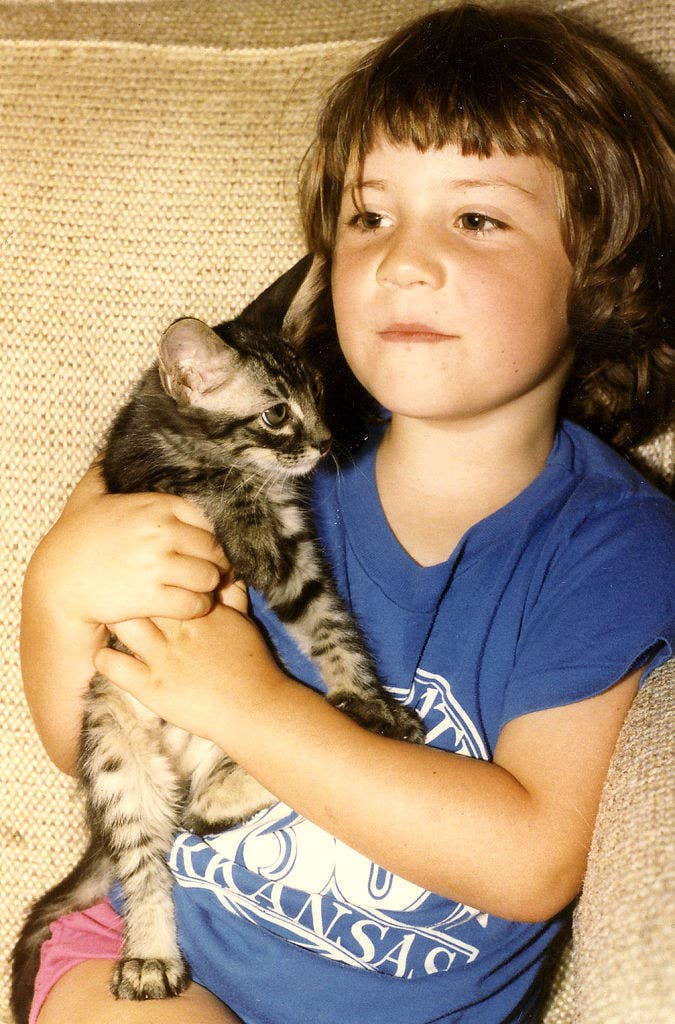

I immediately found that adults liked to argue with me about my vegetarianism. Often, their case boiled down to the differences between farm animals and the other kinds of animals I loved that had led me to this decision. There's a hierarchy of which animals humans are supposed to care for and protect and which ones we raise in captivity and slaughter, but those divisions are convoluted and contradictory. In the U.S., we sign petitions against other countries eating dogs — and yet we euthanize over a million unwanted dogs a year and throw them in dumpsters. We race and slaughter horses, but most people refuse to eat them. We read our kids stories about ugly ducklings and then go to fancy restaurants to eat foie gras, a duck's unnaturally swollen liver caused by weeks of forced tube-feeding. In other countries, they eat some of the animals we love, and love some of the animals we eat. Even my own decisions about animals are complicated: I'm now a vegan, but I have two cats who have to eat meat to be healthy.

These divisions have little to do with any facts about animal intelligence, sentience, or emotion. Farm animals aren't like machines or plants. Pigs are smarter than dogs. Cows like to be cuddled and they cry when their babies are taken away. Chickens can reason.

"Well," these arguments often conclude, "it's OK that it's arbitrary. Humans are special; we're different from other animals, so we can decide who to mourn and who to eat." This is most often where people turn in the end: "Humans, we're different. We're the boss."

This point feels like a parent extinguishing a line of questioning with "because I said so." The question still remains: Why are we special? I understand why people feel more empathy for their own kind than for others, but not how that feeling leads to any logical justification or ethical code. Still, even if I just pretend to get it, let's say humans are special…what kind of special do you really want to be? Isn't having dominion over the earth a great reason to rise above unnecessary cruelty? Don't we want to cause as little suffering as we can? Why not?

In the U.S. alone we slaughtered 9.1 billion land animals for food last year. That's more animals killed to be eaten in the United States than there are human beings on planet Earth. When someone asks how a person who advocates for animals can care "more" about animals than we do about fellow humans, I think they're misunderstanding the kind of problem animal rights advocates are trying to solve; it's cruelty and death on a scale that would literally extinguish human beings from the planet a few times over.

Cecil the lion's death is not on that scale. Even if your radical perspective is that all animals' lives are equally important (as PETA's president once infamously put it, "a rat is a pig is a dog is a boy"), Cecil's death would be analogous to the murder of one human being. A human being beloved by his family and important to his local economy, but one person. "But he was an endangered species" is one argument here, which is a fair footnote, but any scientist could explain that the loss of habitat and effects of global warming have a much greater effect on lion populations than game hunting.

A few days ago, I thought Cecil outrage had died down a bit, when thoughtful pieces like Roxane Gay's plea that we show empathy for our fellow humans as well started to emerge from all the noise. Then, there was suddenly a second round of outrage when folks believed Cecil's brother was killed illegally as well. As it turns out, Jericho the lion both is alive and is not Cecil's brother at all. Now attention has turned to restricting lion hunting, with some U.S. lawmakers calling for a change and airlines adjusting their policies to disallow lion trophies on board their planes.

I'm torn about the Cecil story's place in the grand scheme of outrage and animals, but I do find it hopeful that so many people are capable of experiencing so much grief and empathy toward another species. Perhaps some of them will experience the same kind of turning point I did as a kid. Maybe those upset over Cecil today will soon start to consider the connections among animals — who we are, who we love, and who we eat.