CAIRO — Ibrahim Sayed Metwaly tends to place one hand on his abdomen when he speaks. The 52-year-old is suffering from advanced, and untreated, hepatitis C, and the yellow tinge to his skin suggests that his liver has begun to fail.

"I don't get any treatment. For one and a half years I have been going to the doctors to get the papers signed, the tests completed, but still I get no treatment," he said, frustration evident in his voice. "I need the medicine. All I want is the medicine. I am getting sicker and still, I have no medicine."

Ahmed Ahly, a taxi driver, is supporting two handicapped daughters and does not have the time, or money, to receive treatment for hepatitis C. Teacher Sara Sweif is pregnant, and she does not know how she will prevent her baby from becoming infected with the disease. And former storekeeper Farim Shabany is dying from advanced liver failure after living decades with hepatitis C and using only home remedies, like onion and warm salt water.

With World Health Organization estimates that up to 20% of Egyptians carry the virus, Metwaly, Ahly, and Sweif are just a small snapshot of the Egyptians for whom a "miracle cure" could change everything. Earlier this month, when news spread that the Egyptian military had come up with such a cure, which would be 100% effective in curing AIDS in addition to 95% effective in curing hep C, many saw an answer to their problems.

The only problem was that the doctor, Maj. Gen. Ibrahim Abdul Atti, appears to be a fraud. He has since been widely discredited by his peers and has had his credentials questioned. His miracle device appears to be little more than a staple gun with a radio antenna attached.

Dr. Essam Heggy, a scientist and an adviser to Egypt's interim president, said the televised conference by Atti — which panned to show Egyptian army chief Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in the audience — was a "scandal for Egypt" that "hurts the image of scientists and science" in the country. "The real achievement is to realize our problems and resolve them together," he wrote on Facebook, "not to invent illusionary solutions to real problems."

While the miracle cure has now become the punchline of countless jokes, many in Egypt continue to believe in it. Egypt's health ministry has announced that it will reproduce Atti's device and begin offering treatments, and reports have surfaced of Egyptians trying to offer bribes to senior military and health officials who they believe can get them the miracle cure.

Sweif, who is six months pregnant with her first child, boasts that she has convinced her husband to sell the family car in order to put aside money for the treatment she feels the army can provide.

"I am sure we will need money for this," she said, speaking from a market near her home in Cairo's Midan Kit Kat neighborhood. "We will need money to pay for the treatment and also for the [bribes] to get on the list of those to be treated."

She believes that a secret list is being composed of those who will get first priority to the army's new cure, and wants to ensure that her name is included. While the government-run institute in which she currently receives treatments for free has told her they can help prevent the virus from transferring to her baby, she appears to much prefer a cure, as promised by the army.

"I want to be without this virus — only our army can give me that," she says.

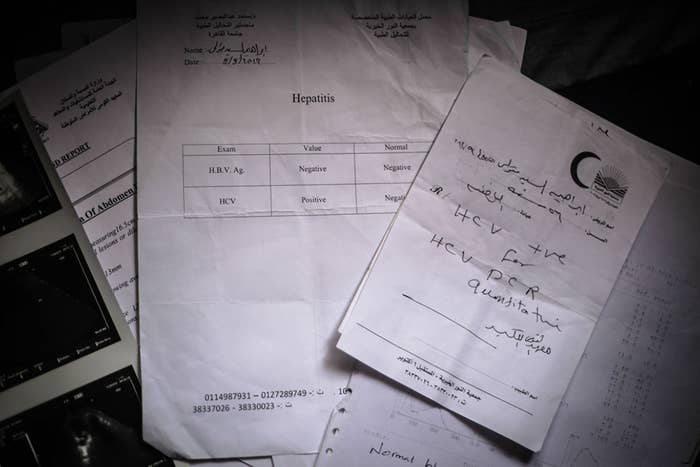

On the outskirts of Cairo's Six of October suburb, Metwaly also hopes to receive the new army treatment. He holds up a file in which his various scans and test results are collected — proof, he says, that he has been jumping through every bureaucratic hoop and still remains without treatment.

"Every time I go to the doctor I have to take two or three modes of transportation, and it takes three to four hours, and still I get no treatment, only more tests," said Metwaly, who moves gingerly and winces as he sits up. He said he only discovered he had hepatitis C a year and a half ago, and it is already well advanced.

"I heard about the army, that they have a cure, and my hope is to get it," said Metwaly. "I don't know any information or details about it. I heard they created a device, and I can only hope my name is on the list of those who will get treatment. … I am not bothering myself about bribes, or trying to get insider help, because it won't happen. I can only hope that everyone will get the treatment."

He, like many, thinks it is the government's job to provide a cure for hep C. The virus's high prevalence in Egypt is in part due to a mass state campaign in the 1960s and 1970s to treat schistosomiasis (also known as bilharzia), a water-borne disease that was at one time endemic in Egypt. The treatment campaigns, which involved repeated injections, used the same needles repeatedly and did not properly sterilize their equipment, leading to a massive spread of hepatitis C throughout Egypt.

Since then, education and treatment options have worsened the situation. And since the disease can lie dormant for decades before causing any symptoms, many people spread it by sharing razors or toothbrushes without realizing that they were infected.

New treatments are emerging for hep C every year, but most are expensive and not 100% effective, leaving many to pin their hopes to the pipe dreams created by the army's statement.

Earlier this month, Egypt's health ministry announced it had reached an agreement to import a new treatment drug for hep C at a reduced cost. The drug, known as Sovaldi, costs $84,000 for a standard 12-week treatment, almost $1,000 per pill per day, according to the California-based Gilead Sciences, which manufacturers the pill. Egypt's health ministry has said that under the agreement reached, there will be a special production line for the pill in Egypt, and the cost will be drastically reduced to $1,900 for a treatment that will last six months.

"It's a great alternative for those who can afford it," said the official from the WHO. "But even at reduced prices, we are looking at a cost that the average Egyptian family couldn't hope to come close to affording."

Metwaly shrugged when asked if he could afford to pay even part of the cost for treatment, saying that it was difficult for him to find the money for the travel costs into central Cairo for treatment.

"The government should give us a cure, and it should be free," he said. "That is what we need."