AMMAN and ISTANBUL — Abu Rahim knows that in many ways, he's exactly the kind of potential terrorist Western governments most fear.

The 29-year-old Jordanian fought last year with ISIS, receiving specialized training in explosives in Syria. Then he returned home to Zarqa, Jordan, before being accepted to an engineering school in Romania, where he lives today on a student visa.

"I feel like I could travel freely in Romania — and to Europe. I feel like once you're there, the borders are not so secure," he told BuzzFeed News in a phone interview from Bucharest, asking to go by his wartime nickname to avoid being identified by authorities as someone who fought with ISIS. "I'm not a bad guy; I'm not a terrorist. But I am aware, in the news, that they are worried about men like me."

In the wake of the attacks in Paris, intelligence agencies worldwide have been forced to look at their security-preparedness anew. The symbolic and well-coordinated attacks of the past — such as 9/11 and the 2005 subway bombings in London — still stick out in the public mind. But government officials increasingly worry about a different and perhaps more elusive kind of threat: "Fairly low-tech attacks," as one Western official tracking terrorist groups described them, that focus on "soft targets," like a supermarket or a newspaper.

The planning of these attacks can be small-scale enough to fly under the radar — and they could be carried out by someone with limited connections among established extremist groups. And such plots become all the more lethal in the hands of a veteran of one of the world's ever-expanding jihadi battlefields: Iraq, Syria, Libya, Mali, Yemen.

It's this threat exactly that the Paris attacks — and ensuing wave of arrests elsewhere in Europe, some targeting recent returnees from the war in Syria — hammered home.

Western officials present it as a dangerous hybrid of the "lone wolf" model of terrorism and the high-profile attacks involving significant resources and planning. "I think what we're looking at now is not 'lone wolf' necessarily, nor is it the command-and-control from structured, hierarchy-based organizations as we have seen in the past," said Alexander Evans, coordinator of the UN Security Council expert group on al-Qaeda and associates. "It's just flatter and peer-to-peer, inspired by radicalization networks and maybe loosely linked to them."

Terrorist groups seem to have their sights set on this mode of attack. In recent weeks, extremist leaders in Iraq, Gaza, and Yemen have renewed their calls for sympathetic Muslims to carry out attacks in Western countries.

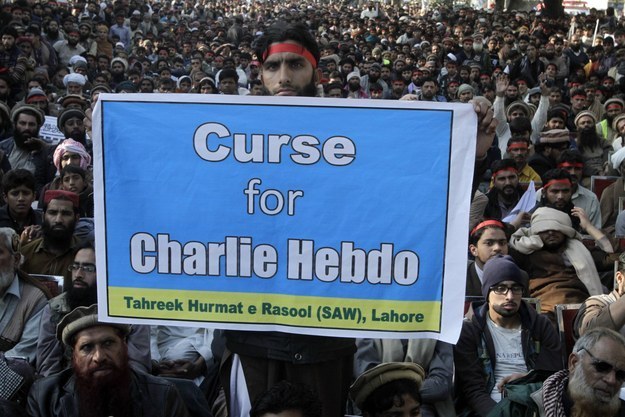

Among those leading the calls was Nasser bin Ali al-Ansi, an official with the Yemen-based al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, which claimed credit for the deadly rampage at the Charlie Hebdo newspaper in Paris. One of the two brothers responsible for the attack reportedly traveled to Yemen in 2011, where he either fought with or received training from the group. "If he is capable to wage individual jihad in the Western countries that fight Islam ... then that is better and more harmful," Ansi said in remarks to the group's media arm, according to the SITE Monitoring group.

It's an idea that's also being discussed by members of extremist groups on the ground. An official with Jabhat al-Nusra, al-Qaeda's affiliate in Syria, said it would be "easy" for the Western citizens fighting with the group to launch attacks at home. "All the foreign jihadis fighting with Nusra, they can go back to their home countries, and it's easy for them to make bombs and find weapons," the official, who goes by the nom de guerre Abu Mariya al-Souri, said in a phone interview from the Turkey-Syria border. "They've spent years fighting. They've learned everything about how to wage jihad. And the Western governments don't know who went to jihad and who came back."

Western governments are faced with a difficult challenge in such a scenario: Potential attackers may be more capable than a typical "lone wolf," while operating with a relative independence that makes them difficult to track. Battlefields like Syria, meanwhile, continue to draw in more recruits. The U.N. has estimated that some 15,000 foreigners have traveled to Syria to fight with ISIS and other extremist groups.

"It's not as if the threat of more organized attacks has gone away," said Evans, the UN expert on terrorist groups. "But the challenge here is the very large numbers, and it's not always people who are known to governments."

Intelligence agencies in the West are "struggling to deal with the new matrix" of lone-wolf-style attacks, said one U.S. security official based in Jordan.

"What do we do? Do we create a psychological profile test for every individual who watches ISIS videos online, or attends a certain mosque? Do we have a threat level indicator that monitors these individuals?" said the official, who asked to remain anonymous because he did not have permission to speak with the media. "We are talking about a huge, huge dedication of manpower here. Many of these individuals do their best to hide their intentions before the attack."

The question of who to watch, and to what extent they should be monitored, has become part of a larger, global debate over how far a government should be able to intrude into the lives of private citizens. In Israel, where lone-wolf-style attacks are occurring with increasing frequency, security officials are asking similar questions.

"How do we know what is going on in someone's head?" said an Israeli security officer who briefed BuzzFeed News last month following an attack on a synagogue in Jerusalem in which two Palestinian cousins, identified by Israeli police as lone wolves, shot and stabbed five people to death. "Sometimes there are indications, other times there are not."

The officer added: "We are dealing with this here in Israel, but Europe and the U.S. must concern themselves with this too."

A U.S. government official who tracks armed groups in Syria called the Paris attacks a new kind of terrorism — conducted by people with some terrorist connections who operate "largely on their own." He said this was the kind of attack increasingly feared from veterans of Iraq and Syria: "The returnees, the Syria veterans, all have the potential."

He added: "It's like hackers, unidentified kamikazes. It can come up anywhere there's someone with an [extremist mindset] and a web connection. No one's ready for [it]."

While the facts of the Paris attack are still being established, the Kouachi brothers, who killed 12 people in their assault on the Charlie Hebdo newspaper offices before another attacker seized a kosher grocery two days later, killing four hostages, appear to hem to this new and advanced model of lone-wolf-style attacks.

Chérif Kouachi had tried to join the fight against U.S. forces in Iraq. He and his brother, Said Kouachi, had longstanding ties to France's jihadi community, and told reporters following the attack that they were with al-Qaeda. Yet a definitive link between the Kouachi brothers and al-Qaeda has yet to be established. While Amedy Coulibaly swore allegiance to ISIS in a video released after he killed a policewoman and four hostages in a kosher market, no formal links between Coulibaly and ISIS have yet been discovered.

"Terrorist attacks by jihadist groups in the past have fallen into a range between locally organized attacks and those sponsored by a group and tightly controlled by the sponsor," said J.M. Berger, a fellow at the Brookings Institution and the author of an upcoming book about ISIS. "The balance has decidedly shifted toward local and self-organization."

The U.S. intelligence official in Jordan said that part of the shift away from well-organized, coordinated attacks was due to increased surveillance of the groups.

"The less communication they have between themselves and the person carrying out the attack, the harder it is for us to gather intelligence or intercept that person," the official said. "If they train someone in how to shoot a gun, and then six years later [that] person, on their own initiative, takes a gun and opens fire at a schoolyard next door to their apartment… Well, you can see the problems we would have in preventing that attack."

Interviews with former jihadis show the small, closed world in which they operate.

A 30-year-old former rebel in northern Syria who calls himself Basel spent much of the country's civil war running a camp that got new fighters battle-ready. He said he trained more than 1,000, including hundreds of foreign jihadis, teaching them to fire automatic weapons and make bombs. Many ended up with Nusra and ISIS.

Basel said he couldn't imagine his former charges committing an atrocity like the Paris attacks. "If they go back to their homeland and commit a terrorist act, of course it's absolutely wrong," he said.

There are trainers like Basel across battle-torn Syria and Iraq. While he and others train fighters with the intention of having them fight the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad, ISIS has boasted of its own training camps and has also called on its followers to launch attacks in the West, while al-Qaeda continues to plan its own.

Amr Medhat, an Egyptian, traveled to Libya in Feb. 2011 to fight after being radicalized at a small Cairo mosque. After the indoctrination was complete, said Mehdat, who renounced violence last year, "you are ready to do anything. You need nothing but a gun to kill."

And that needs no direction from a central leader, he said.

"[ISIS leader] Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi will not give you a direct order, and jihad isn't an organization," he said. "Our imams teach us that it's all about heart, so what I understand I will apply by myself. This is the most dangerous thing about jihad. It's not an organized organization. It's an idea — a very flexible idea."

With additional reporting by Maged Atef in Cairo and Adam Serwer in New York.