"Rape culture" is a culture in which sexual violence is considered the norm — in which people aren't taught not to rape, but are taught not to be raped. The term was first used by feminists in the 1970s but has become popular in recent years as more survivors share their stories.

Here, a beginner's guide to the major elements of rape culture.

Anyone Can Be a Rapist

The defining narrative of rape culture is that a rape happens when a woman is randomly attacked by a stranger hiding in the bushes. And this happens. But it's not the only way it happens, and that narrative can obscure the many other spaces where rape occurs.

Laurie Penny sums it up in The Independent:

As a culture, we still refuse collectively to accept that most rapes are committed by ordinary men, men who have friends and families, men who may even have done great or admirable things with their lives. We refuse to accept that nice guys rape, and they do it often. Part of the reason we haven't accepted it is that it's a painful thing to contemplate – far easier to keep on believing that only evil men rape, only violent, psychotic men lurking in alleyways with pantomime-villain mustaches and knives, than to consider that rape might be something that ordinary men do. Men who might be our friends or colleagues or people we look up to.

The Idea of "Gray Rape"

"Gray rape," as defined by Cosmopolitan, is a sexual encounter that falls "somewhere between consent and denial," where "both parties are unsure of who wanted what." And its prevalence is largely a result of lack of knowledge surrounding what constitutes consent.

According to a U.K. survey of people aged 14–25, nearly one-third of students don't actually learn about consent in mandatory sex-ed classes.

"Rape doesn't just involve someone with a gun to a woman's head," said Michele Decker, a Johns Hopkins professor who wrote commentary for a U.N. report on rape attitudes in six Asian countries. The report found that men would describe actions matching the legal definition of rape — having sex with a woman without consent — but wouldn't use the word "rape."

"People tend to think of rape as something someone else would do," Decker said.

"No Means Yes"

View this video on YouTube

The romantic idea of the "chase" is an old one. Whether it's on TV, in music, or in movies, the back-and-forth between a man and a woman can, of course, be romantic. And while it might seem not inherently malicious — "Blurred Lines" or "Baby, It's Cold Outside," for instance — an important piece in tackling rape culture is acknowledging the importance of personal space and decision-making.

"No" meaning "yes" isn't cut-and-dry. For instance, in the BDSM communities, "no" can absolutely mean "yes." But as Jessica Valenti writes in The Nation, the problem is that consent isn't the default:

Until American culture and law frames sexual consent as proactively, enthusiastically given, there will be no justice for rape victims. It's time for the U.S. to lose the " 'no' means no" model for understanding sexual assault and focus on "only 'yes' means yes" instead.

Victim Blaming

In the early hours of Jan. 8, 2012, a 14-year-old Missouri girl was allegedly raped by a Maryville High School football player after passing out drunk.

In the early hours of Aug. 12, 2012, a 16-year-old West Virginia girl was raped by two Steubenville High School football players after passing out drunk.

Both cases received national media attention — though only the Steubenville case resulted in conviction, and in the Maryville case, the victim, Daisy Coleman, decided to identify herself. But the critical similarity was the treatment of both girls, who were (a) intoxicated, and (b) accusing boys who lived in tight-knit communities to which the girls did not belong. (Coleman had recently moved to town; the Steubenville teen lived in a different state.)

Shortly after both incidents, friends of the boys hurled insults at the girls on social media. When their stories went national, hostility toward the girls only intensified, with many focusing on what the girls did wrong rather than their alleged attackers.

"Slut" Shaming

There are dozens of examples of a public sex act — assault or not — going viral once photos of it hit the web. Above, on the left, is a photo from what was at the time an alleged sexual assault that took place on a busy street corner during Ohio University's homecoming. Instead of ignoring it, or even calling the police, passersby instead chose to Instagram and Vine it.

On the right is a similar incident that happened to an Irish teenager at an Eminem concert. Photos of her hit Facebook and she quickly became a meme under the name #Slanegirl. The Guardian's Eva Wiseman described the #Slanegirl incident as an extreme but sadly common example of female-focused public humiliation that now happens on an international scale.

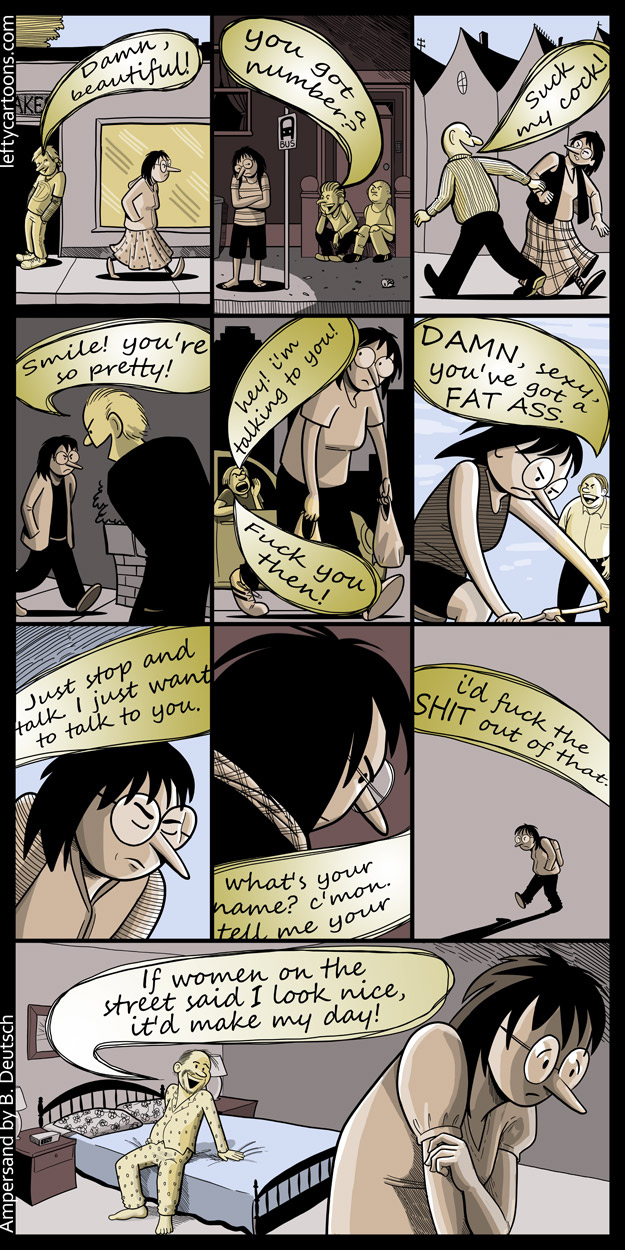

Street Harassment

Street harassment, or cat-calling, can be a daily occurrence for women and only enforces the atmosphere of violence and lack of power that allow a rape culture to thrive. Stopstreetharassment.org explains how a world where men feel comfortable giving unsolicited sexual advances to women they don't know in public is the same world where men feel comfortable with rape. In the explainer, they quote Phaedra Starling's piece "Schrödinger's Rapist":

A man who ignores a woman's NO in a non-sexual setting is more likely to ignore NO in a sexual setting, as well," Starling writes. "If you pursue a conversation when she's tried to cut it off, you send a message. It is that your desire to speak trumps her right to be left alone.

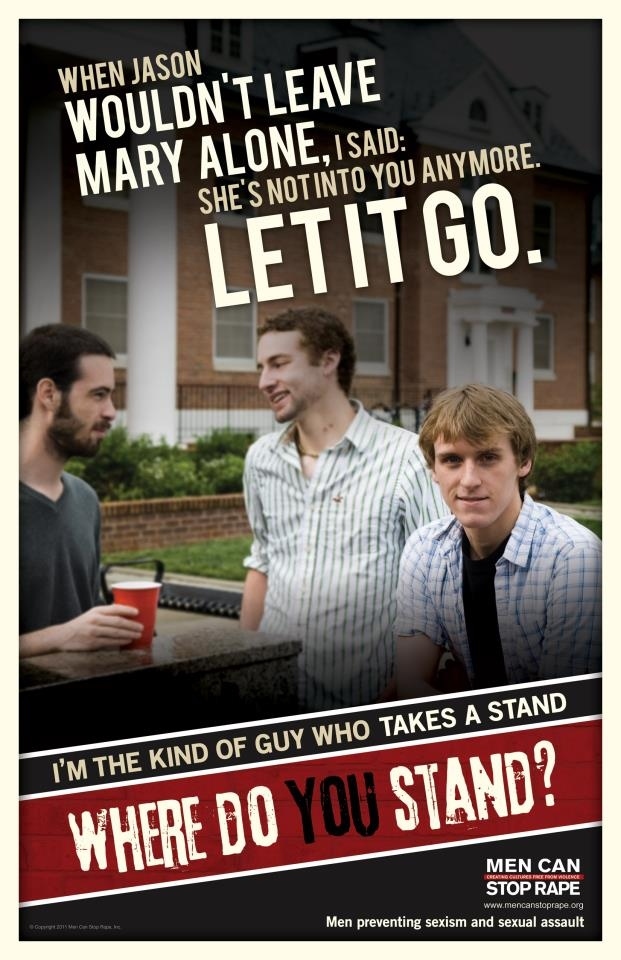

The Myth of Preventing Rape

Many conversations around rape are focused on preventative behavior, like telling women what not to do, what not to wear, or when not to go out. But this logic doesn't place any responsibility on the perpetrators. The old metaphor is that women who dress provocatively are the same as homeowners who don't lock their doors at night. But this argument only further reduces women to objects and asks them to be responsible for preventing their own rape.

From an excellent explainer of rape culture on Shakesville:

Rape culture is telling girls and women to be careful about what you wear, how you wear it, how you carry yourself, where you walk, when you walk there, with whom you walk, whom you trust, what you do, where you do it, with whom you do it, what you drink, how much you drink, whether you make eye contact, if you're alone, if you're with a stranger, if you're in a group, if you're in a group of strangers, if it's dark, if the area is unfamiliar, if you're carrying something, how you carry it, what kind of shoes you're wearing in case you have to run, what kind of purse you carry, what jewelry you wear, what time it is, what street it is, what environment it is, how many people you sleep with, what kind of people you sleep with, who your friends are, to whom you give your number, who's around when the delivery guy comes, to get an apartment where you can see who's at the door before they can see you, to check before you open the door to the delivery guy, to own a dog or a dog-sound-making machine, to get a roommate, to take self-defense, to always be alert always pay attention always watch your back always be aware of your surroundings and never let your guard down for a moment lest you be sexually assaulted and if you are and didn't follow all the rules it's your fault.

Anti-Rape Wear

With products such as the above ribbed anti-rape condom or hairy-legs stockings for women to wear at night, the message is that women should protect themselves — or in the case of the leggings, make women less sexually attractive to men — rather than "men, be careful to respect the personal and sexual boundaries of a woman."

The Globe and Mail's Emma Woolley covered the sad state of anti-rape wear, writing, "ultimately we have to face that this is the state of things: Some women have bought so completely into the inevitability of sexual assault that they are turning to anti-rape devices for security."

Rape Jokes

Beneath the debate over whether rape jokes can be funny is the larger question of whether it's healthy for a society to laugh at the idea of sexual violence.

Lindy West from Jezebel wrote a piece called "How to Make a Rape Joke" during the height of the Daniel Tosh rape joke controversy. For West, Tosh's rape joke, and most other known rape jokes, only further a power dynamic that makes sexual assault seem normal and OK. West writes, "Nobody is saying that you can't talk about rape. Just be a fucking decent person about it or relinquish the moral high ground and be okay with making the world worse."

The "Friend Zone"

This is the idea that a "nice guy" can be put into a sexless friend zone by a woman close to him who unfairly doesn't realize he's the perfect romantic partner for her. The friend zone narrative puts the focus on sex as a reward for being a good person.

Couple this with the fact that according to the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, approximately two-thirds of rapes are committed by someone known to the victim, and suddenly the idea of a friend secretly pining after a girl and also being unable to respect her personal boundaries isn't so romantic.

Blogger Kevin Beirne has an excellent breakdown of how the friend zone leads to rape culture:

The friend zone myth is dangerous and insulting because it perpetuates the idea of women as a prize or a reward for being "nice". It dehumanises women in a way that is more subtle than cat-calling, and this is why so many people fall for it. I fell for it too, when I was younger.

Pickup Artists

View this video on YouTube

The modern Pickup Artist movement involves the belief that not only are women sexual objects that can be attained, but that the process of attaining them is a science that can be gamed. In the above video, a popular YouTube pickup artist literally picks up girls he does not know on a college campus.

Last June, Kickstarter banned a "seduction guide" by a man named Ken Hoinsky, after users discovered Hoinksy's guide was more or less an explainer of how to coerce a woman into having sex with a man.

The next month, XoJane's S. E. Smith pinpointed the issue at the heart of pickup artistry:

Clearly, people can read PUA tips without becoming rapists. They can even identify as PUAs and use some of these techniques in the pursuit of sexual partners without engaging in rape; though I'd still argue that they are participating in a smarmy, objectifying, highly sexist culture that treats women like prizes to be won rather than human beings.

Fear of Reporting

On college campuses — where one in five women are assaulted — only one in eight report it. That's because college-aged victims often don't "see the incidents are harmful or important enough" or "[want] family or other people to know." They feel restricted by "lack of proof," "fear of reprisal by the assailant, fear of being treated with hostility by the police, and anticipation that the police would not believe the incident was serious enough and/or would not want to be bothered with the incident," according to a 2000 National Institute of Justice study.

Even for victims who do end up reporting their assault through police, there's no guarantee the assailant will be convicted. Rape kits are backlogged by the thousands across the U.S., and as a recent White House report explains, "even when arrests are made, prosecutors are often reluctant to take on rape and sexual assault cases."

In the military — where one in three women are assaulted by their fellow service members — the fear of reporting is intensified by chain of command, according to a Department of Defense survey. The DoD found that 62% of women who reported their assaults suffered retaliation for it. According to findings presented in the documentary Invisible War, 33% of servicewomen didn't report their assaults because "the person to report to was a friend of the rapist," while 25% didn't report because "the person to report to was the rapist."

According to RAINN, only about 3% of rapists are ever sentenced to prison. In the military, according to Invisible War, only 2% are convicted.

False Rape Accusations

Around the country, there are cases involving police officers accused of attempting to bully victims into admitting they made up their rapes — a not uncommon practice that has fueled "false rape" statistics.

"False rape" is brought up often by men's rights activists, who generally fear that women — motivated by revenge, or perhaps just regretting sleeping with a man — could use a jury's sympathy to falsely convict men of rape. But this thinking isn't limited to MRAs; Heisman winner Jameis Winston's alleged victim was accused by some in the Florida State community of trying to destroy his career.

But the reality of "false rape" accusations is clear: A woman lying to law enforcement about her assault is both statistically infrequent and difficult to prove. The FBI has called attempts to organize it under one statistic meaningless. There is no formal record of false rape accusations — they do happen, just not often.

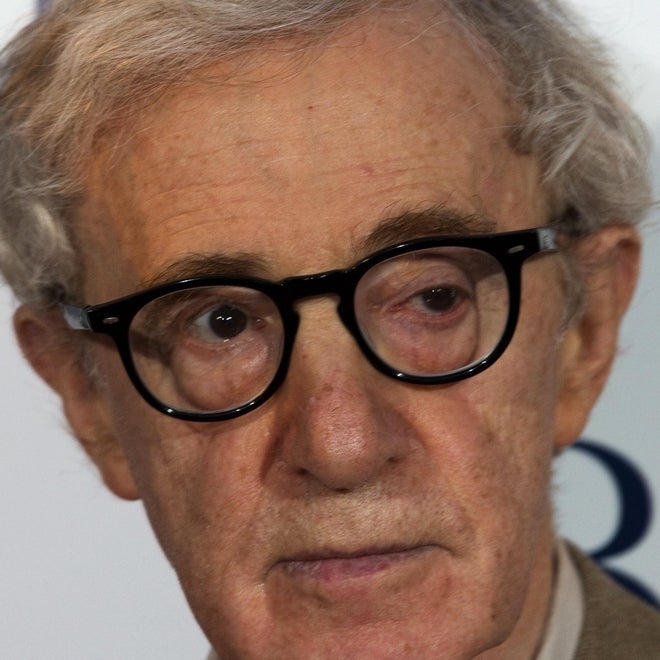

The Power of Celebrity

Last weekend, Dylan Farrow published a letter in the New York Times about being assaulted by her adoptive father Woody Allen at age 7. The response has been largely supportive, but many have expressed that they don't believe her, or don't want to believe her.

While details of the cases vary widely, the reaction to Allen's allegations isn't so different from the reaction to Kobe Bryant's rape allegations in 2003. Bryant is also widely respected, and many of his fans immediately discredited his alleged victim. Today, a decade letter, no one talks about Bryant's alleged history of assault. We also don't talk about Bill Cosby or R. Kelly's alleged abuse, until we're reminded of them decades later — but even then, the conversation reignites only briefly.

Farrow's letter didn't tell us anything new; her allegations have been public for two decades, resurfacing recently in her mother's Vanity Fair profile and Golden Globes tweets. But like Bryant, Woody Allen has been able to shake off these accusations for years, standing tall on his critically acclaimed work, showing us you can avoid being branded a rapist as long as you're talented and respected enough.

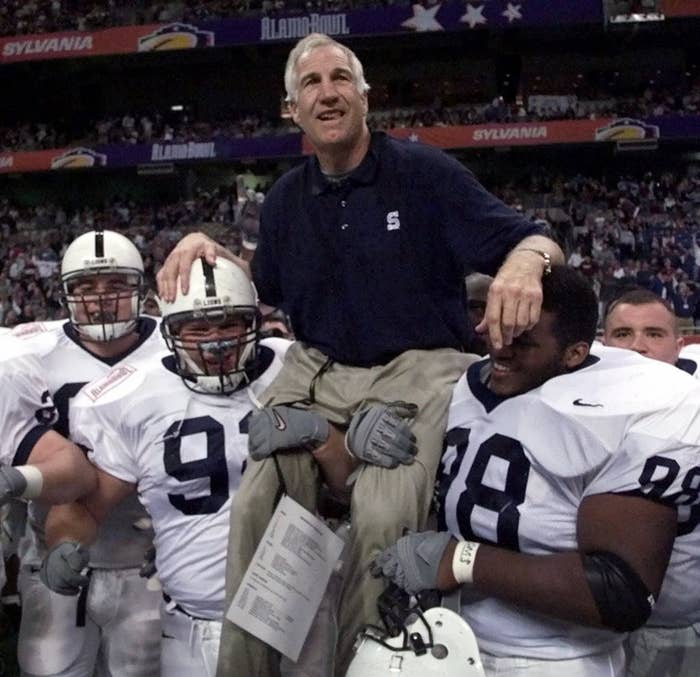

The "Promising Futures" Media Narrative

View this video on YouTube

After Trent Mays and Ma'lik Richmond were convicted and sentenced in Steubenville, CNN's Poppy Harlow described them as "two young men that had such promising futures, star football players, very good students, [who] literally watched as they believed their lives fell apart."

When the New York Times reported on allegations brought against Dominique Strauss-Kahn by a hotel maid, the alleged victim was described by neighbors and co-workers as "a good person" who has "never given a problem for nobody."

Jeffrey Goldberg later wrote in The Atlantic about why he found reporting on alleged victims' personalities — or their attackers' "promising futures" — to be a problem: "I don't understand reporting like this. What is the point? Does it matter that she is friendly? Does it matter that she is a good person? Does it matter that she has never been a problem? Of course not. Rape is rape. The character of the victim is irrelevant."

Male Rape

Since 1927, the legal definition of rape has been "the carnal knowledge of a female, forcibly and against her will." In 2012, the FBI's Uniform Crime Report redefined rape to reflect that not just women can be sexually assaulted. It is now legally defined as "the penetration, no matter how slight, of the vagina or anus with any body part or object, or oral penetration by a sex organ of another person, without the consent of the victim."

That legal distinction is an important one — because male rape, while less common, certainly happens. And it's often only covered in the media when it involves high-profile men of power, like football coaches or priests. Meanwhile, male survivors of rape lack resources and face a different kind of stigma compared with female survivors.

Lack of Attention to Rape in Minority Communities

Rape stories that manage to break into widespread awareness almost always involve involve straight, white victims — even though, according to RAINN, 34% of all American Indian and Alaskan women will survive rape or attempted rape in their lifetimes. That's nearly double the rate for white women (17.7%) and black women (18.8%). It's one in every three women, or "epidemic proportions."

In the LGBT community, the practice of "corrective rape" — when rapists seek to "cure" or "correct" what they see as a problem in someone's sexuality — is another troubling issue that's been given little attention in the U.S.

CORRECTION: CNN's Poppy Harlow reported and gave commentary from the Steubenville trial. An earlier version of this post attributed her quote to host Candy Crowley.