Everywhere he goes, they follow.

Rick Santorum rocketed out of Iowa trying to talk about the economy. The last thing he was looking for was a dustup over gay and lesbian issues. But those issues found him anyway, as they seem to. In New Hampshire and South Carolina, he left "homosexual marriage" out of his stump speech (at least explicitly – the “family” part of “Faith, Family, and Freedom” invokes Santorum’s emphasis on the traditional nuclear family), but still faced a tough college crowd in New Hampshire who booed him for an extended analogy between gay marriage and polygamy. In South Carolina, he was the target of two protests, one of which left him (for the second time) covered in glitter.

His last name has been redefined as a crude bit of scatology, and turned into a joke on Google. Gay activists are now working on turning to his first name into a verb. And Google has ignored Santorum's pleas to reclaim his search results.

Then there are the questions from the press, which won’t stop. If there’s a gay story in the news, there’s a reporter to ask him about. Rick Santorum is happy to talk about gay marriage. But transgender girl scouts? He’ll pass.

"I don't think that's a federal issue," he said when asked in South Carolina, quickly taking the next reporter’s question.

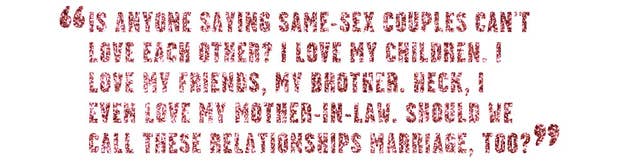

Santorum made his name battling gay rights. But he let the issue define him in 2003, when he told an AP reporter that the definition of marriage should remain traditional and that “not to pick on homosexuality -- it's not, you know, man on child, man on dog, or whatever the case may be.”

"I'm sorry, I didn't think I was going to talk about 'man on dog' with a United States senator, it's sort of freaking me out," the reporter replied in what became a celebrated exchange.

Meanwhile the issue, a promising wedge in the mid-2000s, has lost its charge on the right while the broad public grows more comfortable with a spectrum of gay rights leading up to marriage. And yet Santorum has found himself handcuffed to the issue. His social conservatism – particularly his opposition to abortion – helped win him Iowa. But as he has tried to broaden his message and talk about the economy, he’s found himself trapped in the complex and entertaining politics of gay rights, a prisoner of the gays.

Santorum’s main strategist, John Brabender, told BuzzFeed earlier this month that the candidate hasn’t been seeking these issues out. Santorum, he said, realizes that the economy and national security are closer to the top of voters’ minds. And yet voters, sympathetic and critical, associate Santorum with what he calls moral issues, and sees as part of the fabric of the crisis facing America. And Santorum, Brabender said, isn’t one of those programmed candidates who will just ignore a politically difficult subject for political reasons.

“He’s going to answer the questions,” Brabender said.

And so the issues for which Santorum is famous are now the ones doing him the most harm.

Former South Carolina governor Mark Sanford described the candidate’s poor showing there despite the state’s conservatism in an interview with CNN, saying that normally the state would be “tailor-made” for Santorum.

“But the head wind was, in this case, a lot of folks out of work for social conservatives,” Sanford said. “The economy became pre-eminent and as a consequence Rick didn't do as well as many folks thought he would have.”

Even for voters who agree with him on gay rights, the perception that he’s the candidate of the culture wars has made him unpalatable, said Fred Sainz, the vice president for communications at the gay rights group Human Rights Campaign, which has made Santorum a top target.

Voting for him would be like “ordering Moroccan food at an Italian restaurant,” Sainz said.

And Santorum’s welcome even at conservative gatherings, like a meeting fo the Chamber of Commerce in Columbia, South Carolina last week, has at times been chilly. There attendee Jack Sloane of Charleston told BuzzFeed that Santorum is “a homophobe” and “a religious nut."

That perception has become utterly mainstream.

“Seems like to him gay people – ‘Oh my God, that’s the end of the world.’ He doesn't seem to talk about anything else,” the Tonight Show’s Jay Leno remarked in December.

Santorum, left to his own devices, does not come across as a hater, and though he attacks same-sex marriage, rarely talks about gays and lesbians in the terms with which he’s associated.

During a debate in New Hampshire in early January, Santorum was asked what he would do if one of his sons came out to him.

“I would love him as much as I did the second before he said it,” Santorum replied without hesitation. “And I would try to do everything I can to be as good a father to him as possible.”

It was a powerful moment. Santorum was showing the electorate that he wasn’t going to pander to people who hate gays. But if he was aiming to soften his image, it hasn’t worked. People know too much about him already.

This is due in no small parts to the efforts of the well-organized gay political movement, whose star has risen among the battles over same-sex marriage, and who will never forgive Santorum for his broad opposition to gay rights and for the man-on-dog quote in particular, which turned him into a poster-child for a political class that is still catching up with popular perceptions.

Santorum’s nemesis Dan Savage told BuzzFeed he agrees that Santorum’s positions on gay rights are hurting his chances even among conservatives.

He wrote recently that the “man on dog” interview is the true albatross around the former senator’s neck.

“My readers did not forget that interview—and they made sure no one else did either. Rick Santorum certainly hasn't been able to forget it,” Savage wrote. “Rick can run (for president, from New Hampshire voters chanting "bigot"), but he can't hide.”

He can’t hide even at his own primary night party at The Citadel in South Carolina, where his speech spinning the third-place finish as a victory was followed in short order by an attack from a group of young glitter-bombers. The protesters managed to hit Santorum with glitter as he was signing autographs and were then forcibly removed by police, stealing the spotlight away from the candidate as the room’s focus turned to them.

When Santorum appeared on Fox News a few minutes later, though, there was no glitter visible on him. That, at least, he could control.