India's general election this year will be the largest democratic election that has ever been conducted in the world — and also one of Facebook's most ambitious pushes into electoral politics.

As Indians head to the polls over the next month to elect a new ruling party and prime minister, Facebook has launched a multifaceted campaign in the country, exploring what people want from Facebook on a political level and introducing new features, as likes have surged for candidates.

The scale of the elections, estimated to cost $600 million, is staggering. Ballots will be cast at 930,000 polling booths and 1.4 million electronic voting machines, with 11 million people — both civilians and government officials — helping facilitate. More than 100 million Indians are newly eligible to vote, bringing the total Indian electorate up to 815 million people.

Half of India's total population is younger than 24, and about 150 million people in India's total electoral pool are first-time voters. According to some estimates, more than 40% of India's eligible voters are between 18 and 35 years old. Surveys have found that 70% of all Indian students own smartphones. This is all to say: For the first time in Indian history, there is a significant overlap between the urban, educated, tech-savvy India and the India that lines up to cast its vote.

"Our mission is to make the world more open and connected," Facebook's Public Policy Manager Katie Harbath told BuzzFeed in a phone interview. "Part of that is helping to connect citizens with the people who represent them in government. Elections are the first way that citizens have that opportunity to voice their opinions."

The scale of the Indian elections is also an enormous opportunity for Facebook, which recently announced its ambitions to reach 1 billion users in India. Already, India is the only country aside from the United States where Facebook's consumer base exceeds 100 million, and it's certainly the only country in the world where Facebook can hope to corral 1 billion new users.

"Of the 800+ million people eligible to vote in India, 170 million of them are on the Internet and well over half of Internet users in India are using Facebook," Facebook spokesperson Andrew Stone told BuzzFeed in an email. "In fact, you may have seen that just this morning we made the announcement about having reached 100 million active Facebook users in India."

Elections serve as an excellent recruiting tool for Facebook and similar initiatives have been deployed in other nations holding elections in recent years. This year, that includes Brazil, Indonesia, and Colombia, as well as the European parliament elections. Last year, Facebook launched similar initiatives in Germany and Australia, when those countries were hosting elections.

And Facebook, in turn, is emerging as an increasingly central medium for electoral politics, with both paid ads and widely shared content within its networks emerging as key ways for politicians to communicate with voters.

So far, the Facebook India campaign has been both exploratory but also assertive, gradually introducing new features into the feeds of users.

On March 26, a week and a half before voting first opened, Facebook India put out an open call to ask users how they were using Facebook in the elections.

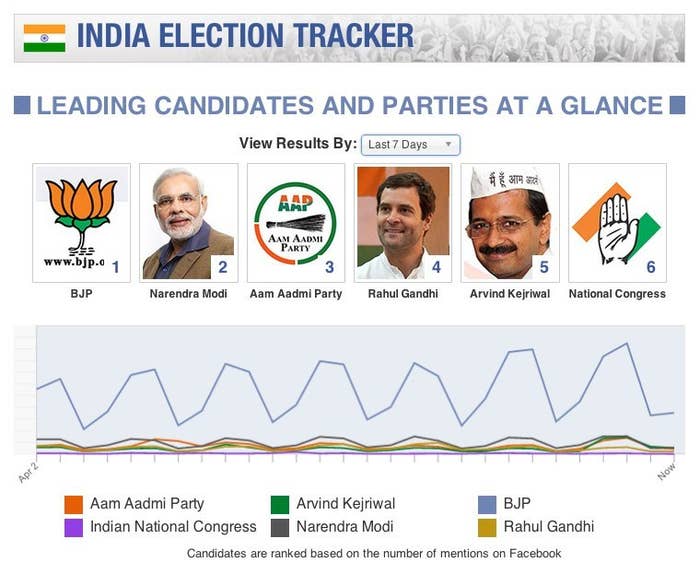

In early March when the elections were first announced, Facebook India launched an election tracker that tracks mentions of the leading candidates and parties, ranking them from most mentioned to least. This is modeled after a similar app Facebook launched in the United States during the 2012 presidential elections.

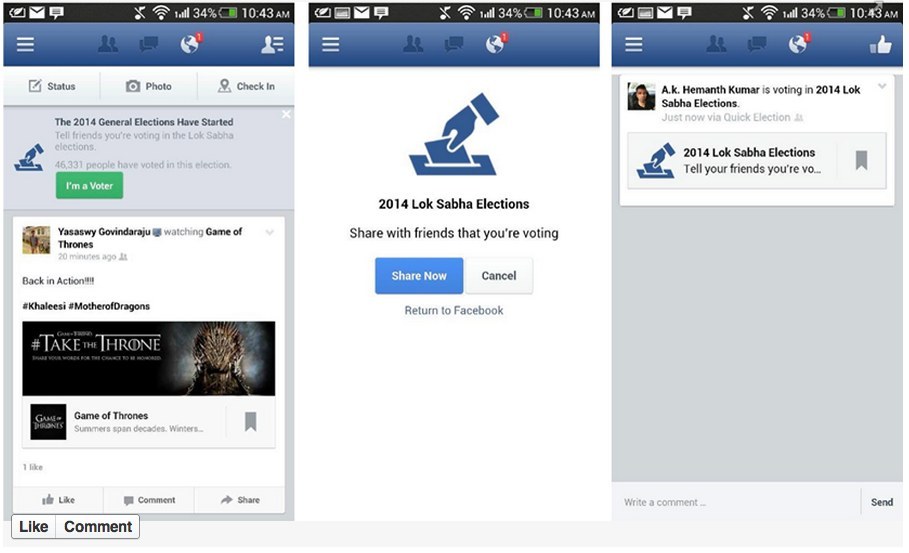

As of Wednesday, the top of the Facebook India homepage now features an "I'm a Voter" button, which will remain visible for the duration of the Indian elections. Clicking it allows users to share with all of their friends that they voted. The visibility of this button is contingent on voting eligibility; it is only visible to Facebook users over the age of 18, and only on days when voting is taking place in the region they are in.

The idea is to drive Indians to the polling stations. A UC San Diego study during the 2012 U.S. presidential elections found that social pressures, specifically on social networks and specifically from close connections, are a major influence on whether individuals vote or not. Although 4% of Facebook users who clicked the "I voted" button on Facebook admitted to not actually having voted, rates of voting were highest among those who had seen a message seeing that their friends had voted — particularly close friends.

In an election already historic for its scale, this Facebook initiative might — this is the hope — increase voter turnout by acting as a multiplier.

According to data provided by Facebook, mentions of the word "election" increased by 561% among Facebook users in India within the first 24 hours following the announcement of this year's elections, and mentions of the "Lok Sabha" (India's lower house of parliament, in which parties are competing for seats) increased by 150%.

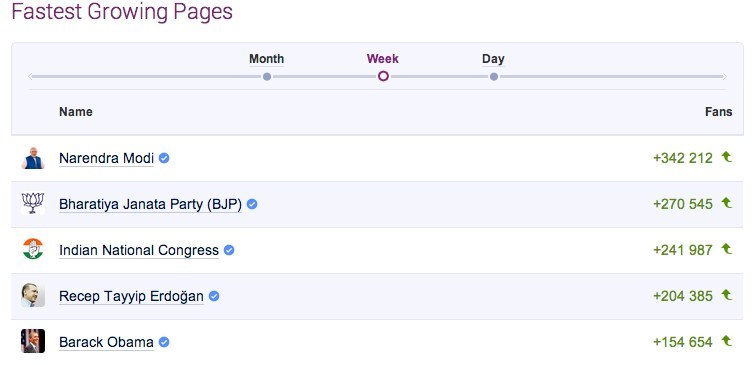

Narendra Modi, one of of India's two front-running prime ministerial candidates, has more than 12 million likes on his Facebook page (having gained 48,555 in the last day alone, at the time of writing). Among global politicians' Facebook popularity, that number ranks him second only to President Barack Obama. In the last week, Facebook pages for Indian politicians and parties have garnered likes faster than any other political pages worldwide.

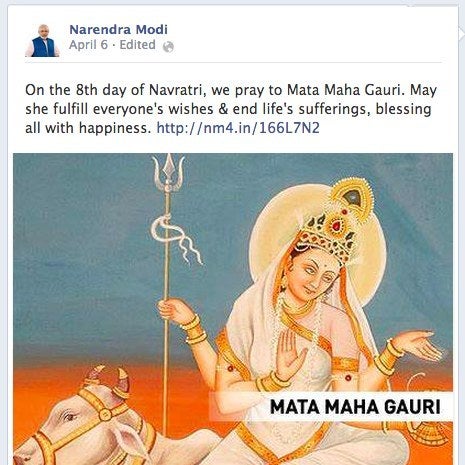

Modi's Facebook posts are comprised mainly of campaign updates, calls for volunteers, criticism of his opponents, and content about Hinduism. Modi and his party, the BJP or Bharatiya Janata Party, have consistently garnered more mentions in real time than any of their competitors.

Even at a rudimentary glance, Facebook's electoral data illustrates that Modi is more talked about than his primary challenger Rahul Gandhi among India's Facebook users, i.e., among India's educated youth. The data also suggests Modi's fan base extends far beyond the more conservative and older demographic that he has conventionally been associated with.

Meanwhile, Rahul Gandhi has less than a 100th of Modi's Facebook following, and doesn't even exist on Twitter. (Modi has more than 3.5 million Twitter followers.)

For all its efforts, the social network is wary of seeming too involved with the outcome. "[Facebook is] not trying to predict any elections," Harbath said on the phone. "We are an open platform that all the candidates and political parties can use to communicate and engage with many of the voters in the Indian elections."

Indeed, it's difficult to interpret Modi's and the BJP's overwhelming Facebook popularity relative to their competitors — whether they simply appeal more to Facebook power users, or whether something else is work.

Only about an eighth of eligible Indian voters are on Facebook — a figure the company is aiming to change — and only 74% of India is even literate.

Harbath said Facebook is not discouraged by that fact. "Conversations aren't restricted to Facebook. People might be conversing with candidates or political parties on Facebook, but they are continuing those conversations in their communities, with their friends and neighbors … It ends up being a lot of conversations on the ground." And of course, some of those conversations may translate into new users.