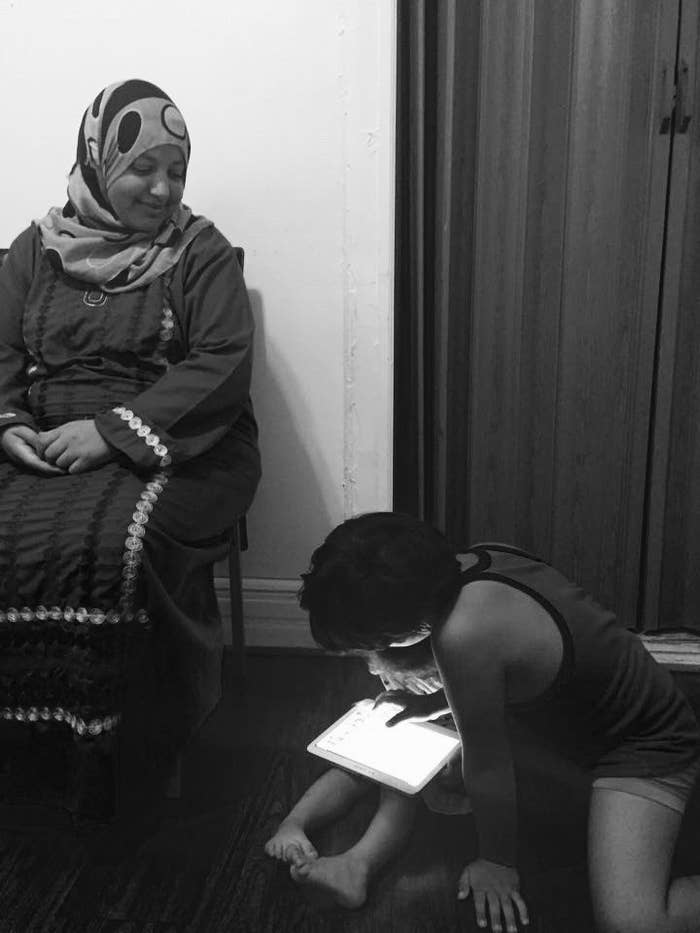

For 33-year-old Soha Hossam, it’s the small things — like watching her son and daughter squabble over an iPad — that reassure her that her family’s grueling, two-year long journey from war-torn Syria to the United States was worthwhile.

Soha lives with her family — Wesam, age 6; Mayesa, 3; and her husband, Hossam Alroustom Maen — in a dilapidated Jersey City walk-up apartment, where no two chairs match. According to data collected by the Church World Service (CWS), a federal government contractor that helps refugees resettle, they are four of just twenty Syrians who have been legally admitted for resettlement in New Jersey since June 2015 — more than a month before the world’s consciousness was suddenly and sharply turned to the heartrending refugee crisis that has seen thousands of Syrians flee their war-torn country for Europe.

“Wesam is autistic,” Soha said as she fiddles with her headscarf and keeps an eye on the children, who are absorbed in an episode of Koky Kids on TV. “The sounds from the incessant bombs and explosions used to make him very anxious.” The very building they lived in, in Homs — one of the focal points of a civil war between the government and armed rebels — was often attacked, she said.

So in the summer of 2013, she and her husband — who worked as a laborer and owned a market in Homs — decided they would be better off, and safer, making a long and dangerous journey out of their home country to seek refuge elsewhere. They packed up their bags with a few basic clothing items and left. The only thing that survived the journey is a long black coat. It’s what Soha wears when she steps outdoors.

Nearly 4 million refugees registered with the United Nations have fled Syria since the outbreak of the war in 2011, according to the UNHCR. Soha’s family members are part of the 1,500 refugees that have been resettled into the U.S. since then — though the number will likely increase after President Obama on Thursday instructed the State Department to take in an additional 10,000 Syrian refugees in the upcoming fiscal year. For the families that have managed to flee, the journey is not an easy one. And while Soha and other families who have resettled are grateful, they also have to encounter new struggles: rebuilding their lives in a completely new country while constantly worrying about family and friends they left behind.

Soha and Hossam and their children first boarded a two-hour bus to Ratain village in the north near Aleppo, crossed the desert between the Syrian-Jordan border at night with the help of a bedouin, and finally arrived at the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan, which is currently home to nearly 80,000 people, according to UNHCR.

“The camp was very crowded and there was no electricity or bathrooms,” said Soha. “The kids even fell sick because of the unclean water.” The conditions at the camp were detrimental to the children’s health – at one point, Jordanian forces fired tear gas into the camp to reportedly quell a protest over the living situation – triggered anxiety attacks in Wesam. The family cobbled together the funds to pay off a few locals who moved them to a house in Irbid, about an hour’s drive away.

They lived in Irbid for a year, until the Jordanian army caught Hossam working on a non-working visa. They ordered him and his family to either go back to the refugee camp with his family or return to Syria. Hossam and Soha boarded a bus to the UNHCR office, where their application for resettlement was approved due to Wesam’s medical condition. About two years later, they made it to the United States in June 2015 without even a pair of shoes from Syria.

________

Another Syrian family lives about a 10-minute drive from Soha and Hossam’s Jersey City apartment. This family — a father, his wife, and three children — arrived barely three weeks ago from Homs. They requested anonymity because, the father said, “my brothers are in Homs and if anyone sees our pictures, [the Assad regime] will torture them and kill them.” he said.

He calls out to his son to bring in a standing fan and begins describing in vivid detail the atrocities and reality of Homs, which he refers to as “the cradle of the revolution” against President Bashar Hafez al-Assad’s security forces.

A mechanic back home, his family home was destroyed by a random missile, and most of his extended family was tortured, injured, or killed by barrel bombs, tanks, and rockets. “The government forces are the real deal and the real threat. Da’esh (ISIS) is simply a sitcom,” he said, adding that he knows of mosques blown up by the government during Ramadan prayers.

The father remembers dates, names, and specific episodes that finally led him to pack two bags in June 2013 and bring his family through Alexandria in Egypt, then Italy, then to the U.S. At one point, he said, he saw neighbors and children from his street losing limbs and being buried alive in the rubble of their homes after 2012. “That’s when we realized we had to flee for the future of our children,” he said.

He recounts his journey to Egypt via Al-Waar in June 2013. Five of them were often given refuge in tiny rooms by locals until constantly moving from one neighborhood to another became a struggle. They made their way to Egypt and spent two years and three months there. He was finally told by UNHCR and the International Center of Migration that the family was being resettled to America. They were given passports and flight tickets to Italy. The father said his family was told, “If you like it, you like it, otherwise too bad, we are moving to the next family.” (Other families were being resettled in New Zealand and Sweden.) They arrived in Jersey City on Aug. 18, 2015.

______

Now safely in the U.S., both families have had to overhaul their lives. Language continues to be the biggest barrier — as all of them speak little or no English. CWS, which helps resettle refugees in the United States, helped them settle into their new homes by getting basic furniture and clothing, procuring an I-94 work permit, and getting food stamps and some money. The organization has also helped men from both families find work according to their skill set: Hossam works as a mover at a nearby warehouse and the other father has found work as a mechanic.

Their wives raise the children and work keeping the home together. “I wasn’t very happy the first week when we got here,” said Soha. “But things are getting better now.” She even enjoys going out and taking the children to a park on their block.

The children from the second family have enrolled in an English language learning school. Wesam still doesn’t have a school to go to — CWS is helping the family find a special needs school in the area. Both families’ social interaction is limited to the handful of other Syrians who have been resettled in New Jersey — just last week, they all toured New York city together — but once a week they make it a point to talk to their relatives in Homs.

Whatsapp calls and messages are the easiest mode of communication, but conversations always end on a depressing note. Soha’s messages with her sister — who is still trapped with her children in the heavily barricaded Al- Waar neighborhood in Homs — are a reminder that home as they remember it does not exist anymore. “The government’s security forces are making them live like chickens in their own city,” said the second family’s father, emphasizing that those who haven’t been able to escape Homs by air or sea are like prisoners trapped in their own country.

The images earlier this month of 3-year-old Aylan Kurdi, who drowned on a Turkish beach while fleeing the war in Syria, shocked the world into awareness and, in some ways, action. But these families said they are well aware that there are many more children suffering the same fate. “We have lived through the war, so we understand the suffering,” said Soha.

The father of the second family said that up until the picture surfaced, the world had chosen to close its eyes. “We asked the international community for help six months after the conflict started. It’s been five years and they still haven’t done anything to help,” he said. He’s also cognizant of the ongoing refugee crisis and feels that the EU is definitely more accepting than the United States. But he is at a loss for words when asked about the Syrian people as a whole. “I don’t know what will change,” he said, shaking his head in despair.

Despite being grateful for the safety of their families and for not having to ford the Mediterranean with smugglers — a route that claims lives every week — there is a looming sense of yearning from both families when asked if they would like to return to Syria.

“There is no human being who would not love to return to his homeland,” said the second father, remembering his group of friends and community who have been split up due to the war.

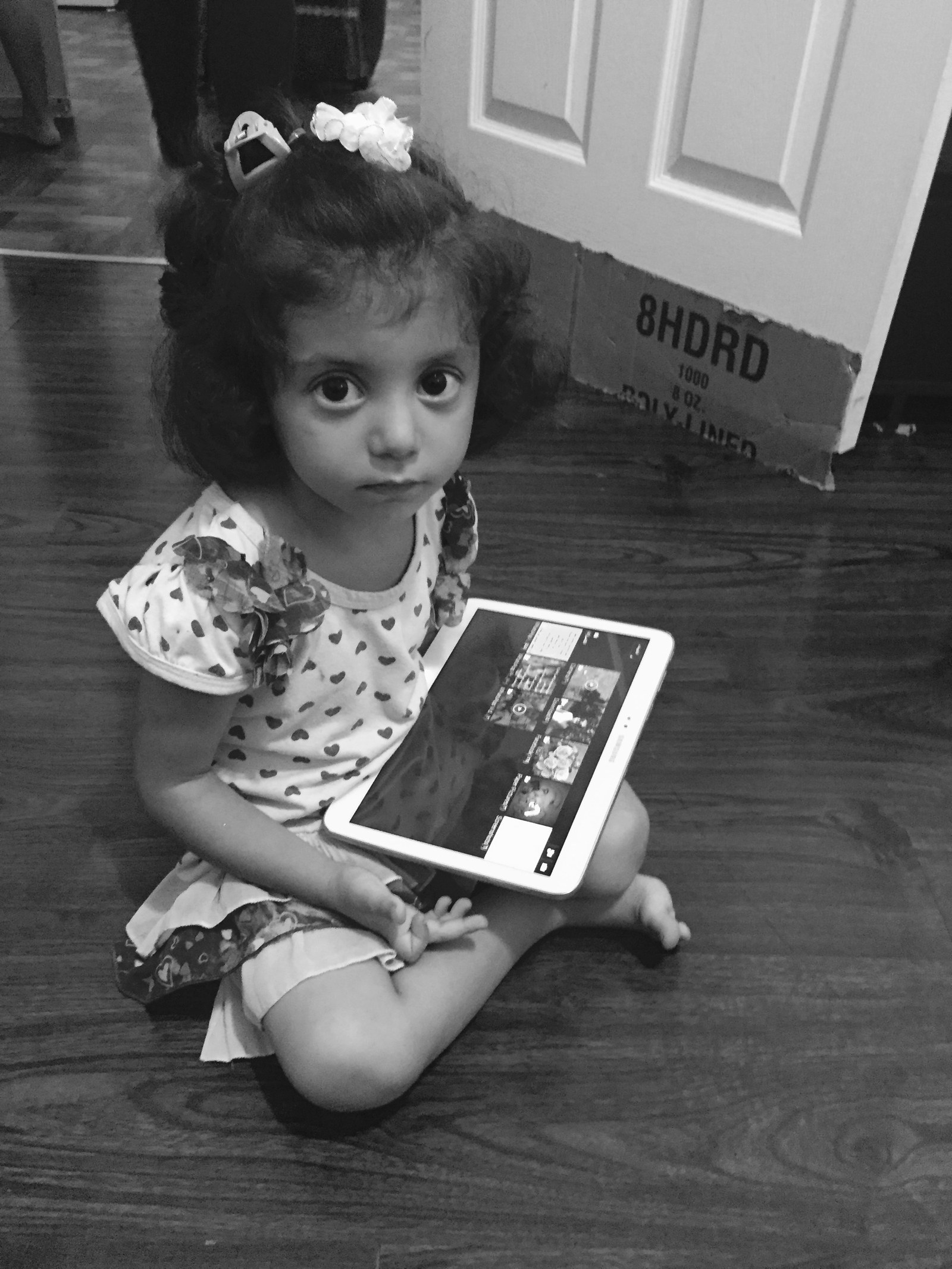

It’s not just the adults who seem to have left a piece of their heart back home. As soon as they hear the word Homs or Syria, the children scuffle to show off as many pictures of their ravaged hometown on their Samsung tablets. When asked about the one item they wished they had brought with them to America, the second family’s 11-year-old daughter answers without a second thought. “A Syrian flag. The free one.”