Ten years on, the ghosts of Hurricane Katrina still haunt the Gulf Coast of Louisiana and Mississippi. More than 1,200 people died. Property damage was estimated at $108 billion, making Katrina by far the costliest Atlantic storm to hit the United States.

BuzzFeed News has pulled together the facts, figures, and maps that place this epic disaster in context.

The annual Atlantic hurricane season officially begins on June 1, and is usually over by the end of November. During that period, cyclones form over warm waters in the tropics. Water evaporating from the sea surface, combined with the Earth's rotation, forms storm systems that slowly spin in anticlockwise direction, with a zone of low pressure at their center.

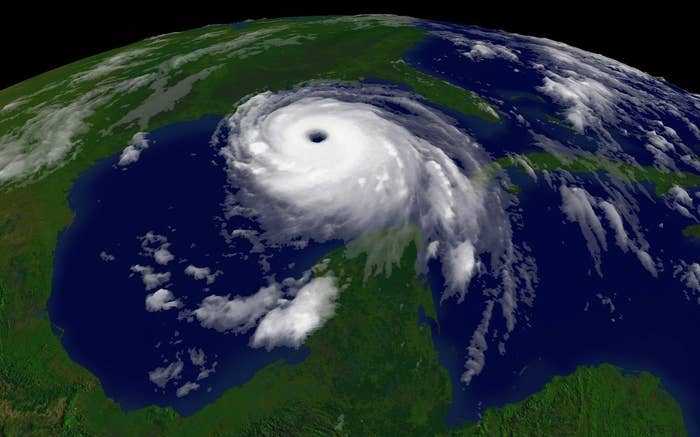

As these storms grow in intensity, they typically shift north and west, threatening the Caribbean and the U.S. Gulf and Atlantic coasts with high winds, heavy rain, and surging seas before veering off to the northeast. They can grow to an enormous size — Katrina measured about 400 miles across when it made landfall in Louisiana.

Once the maximum sustained wind speed in an Atlantic cyclone exceeds 39 mph, it is classed as a tropical storm. When winds top 74 mph, it is called a hurricane.

The chart above shows every hurricane season since 1980. But even if you go all the way to 1851, when current records began, there is no season that matches 2005. It boasted 28 tropical storms, 15 of which attained hurricane strength.

There were so many storms in 2005, in fact, that the planned alphabetical roster of men's and women's names was exhausted, and hurricane watchers started naming them after letters of the Greek alphabet. The final storm of the season, Zeta, raged on into January 2006.

2. Here is that hellish season, showing the path of each storm.

As long as Atlantic cyclones remain out to sea, they pose a limited threat. But in 2005, Katrina wasn't the only major hurricane to terrorize the U.S. Gulf Coast. In July, Hurricane Dennis made landfall near Pensacola, Florida. One month after Katrina, Hurricane Rita battered the coasts of Texas and Louisiana. And in October, Hurricane Wilma traversed southern Florida on its way out from the Gulf of Mexico into the Atlantic.

The combined effects of these storms made 2005 a record year for damage from Atlantic storms, pushing the total economic losses beyond $150 billion.

3. Katrina killed at least 1,200 people, more than any storm since 1928.

Katrina's death toll was unprecedented in the modern era. This table lists every Atlantic tropical cyclone known to have killed 25 or more people in the continental United States, from records compiled by the National Hurricane Center (NHC) in Miami.

The NHC conservatively estimates that Katrina directly caused at least 1,200 U.S. deaths. This excludes several hundred people killed by knock-on effects of the disaster — mostly because they couldn't get essential medical care, or suffered stress-related heart attacks or strokes. Some estimates put the total toll, including these indirect casualties, at more than 1,800.

Still, even Katrina pales beside the hurricane that hit Galveston Island and the neighboring Texas coast in 1900, when a surge of up to 15 feet above normal sea level drowned some 8,000 people. Twenty-eight years later, another devastating hurricane whipped up Florida's Lake Okeechobee, inundating its shores and killing at least 2,500.

These disasters, like most of the leading killers on the NHC's list of destructive storms, happened before the 1930s, when the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers stepped up efforts to build dikes, levees, and waterways designed to keep storm waters out of vulnerable cities.

Thanks to this huge flood protection program, residential areas of New Orleans — some of them lying below sea level — were by 2005 ringed with some 350 miles of levees and concrete flood walls. But these defenses proved utterly inadequate on August 29 of that year, as Katrina bore down on the city.

4. Katrina was an unusually intense storm, even though its winds were nothing special.

This chart shows all the Atlantic cyclones in the historical record for which the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has records of their maximum wind speed and minimum air pressure as they made landfall. (NOAA didn't routinely record this data from 1951 to 1990.) The deadliest storms are scaled according to the number of people killed.

Wind speed and air pressure are the two main measures of a storm's strength — and by the latter measure, Katrina was an unusually strong storm. But for such an intense, low-pressure storm, its winds were nothing extraordinary.

Indeed, by the time Katrina hit the Louisiana coast, with winds of up to 127 mph, it was a Category 3 hurricane on the five-point Saffir/Simpson scale, which rates the danger posed by a hurricane according to its maximum sustained wind speed.

High winds make for striking images, as TV meteorologists struggle to stay on their feet, while warning their viewers to take cover or evacuate. And the scale is easy to understand. "People can relate to a simple number," Katie McDowell Peek, a coastal research scientist at Western Carolina University (WCU) in Cullowhee, North Carolina, told BuzzFeed News.

But there's a problem. The main danger from a hurricane is not wind, but storm surges that can suddenly engulf low-lying coastal areas, putting them under many feet of water.

NOAA is developing new warnings, including maps that show parts of the coast that face a serious risk of flooding. But so far, the Saffir/Simpson categories still dominate media reports.

"We need to focus more on the impacts, and storm surge is the biggest killer," Christopher Landsea of the NHC told BuzzFeed News.

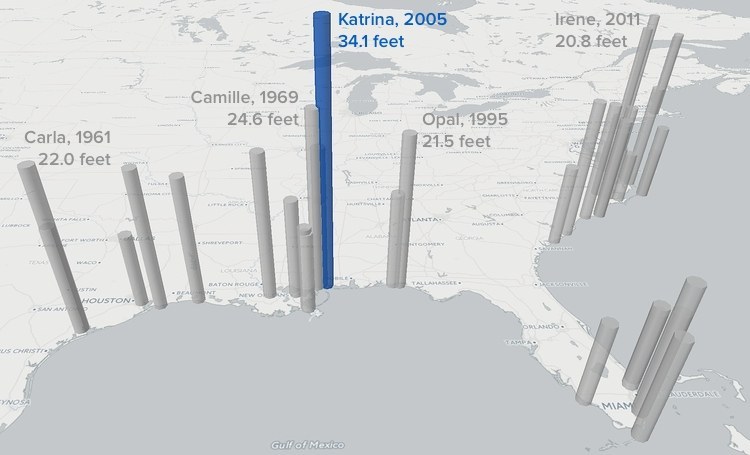

5. Katrina’s flood was the highest on record.

Good data on storm surges is much more sparse than measurements of wind speed and pressure. But according to records of high-water marks compiled by WCU, Katrina was a record setter. The biggest surge was at Biloxi, Mississippi, where the sea rose more than 34 feet above its average level.

The map above shows the relative height and location of the maximum surge for each of the storms in WCU's database, vastly exaggerated as massive columns reaching for the sky.

The height of a storm surge is hard to forecast, as it depends on a complex interplay between low air pressure, winds whipping up water at the surface, and the shape of both coastline and sea bed.

It is also difficult to predict exactly where a storm will hit the coast — forecasts made a day before a storm's landfall can easily be off by 30 miles or so. "And that may be the difference between a 12-foot storm surge and not having your feet wet at all," Landsea said.

6. New Orleans took close to a direct hit — and we were warned what could happen.

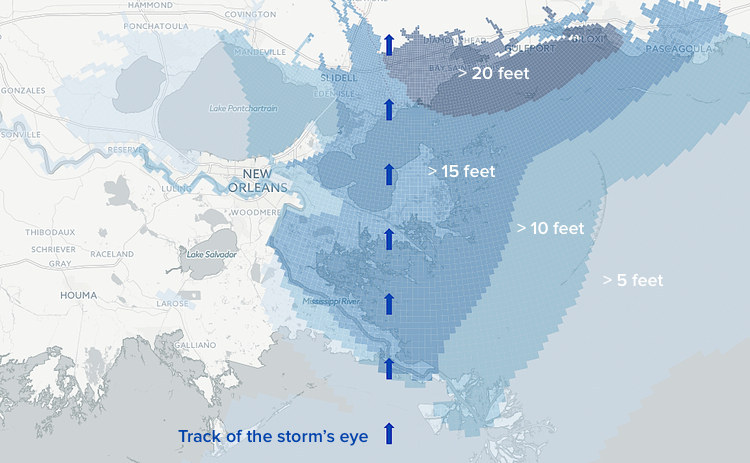

This map shows a simulation of highest water that occurred during Katrina's assault on the Gulf Coast, calculated from weather data by NOAA's Sea, Lake, and Overland Surges from Hurricanes, or SLOSH, computer model.

The deepest floods were East of the storm's center, as counterclockwise winds piled water up onto the shore. New Orleans, meanwhile, faced a twin threat: To the north, Lake Pontchartrain rose more than 10 feet above normal levels, while Lake Borgne, east of the city, was hit by a surge of 15 feet or more. Levees and flood walls holding back both lakes failed, and around 80% of the city was flooded.

With eerie prescience, a similar catastrophe had been considered in 2004, during an exercise called Hurricane Pam, commissioned by the Federal Emergency Management Agency. Pam was a simulated Category 3 hurricane that hit just to the west of New Orleans.

IEM, the disaster consulting firm that ran the simulation, predicted that levees and flood walls would be overtopped, rather than actually giving way. But in terms of the depth and extent of flooding, and the number of buildings destroyed, the simulation was remarkably close to what happened, one year later.

Thankfully, on one key statistic, Katrina was much less severe than Pam. IEM had assumed that only 36% of the region's population would be evacuated, and warned that more than 60,000 people could die. In the event, more than 80% of local residents had left by the time Katrina hit, which minimized casualties.

Since 2005, flood defenses for New Orleans have been comprehensively overhauled. But they cannot guarantee safety in the face of a major hurricane, Robert Young, who heads WCU's Program for the Study of Developed Shorelines, told BuzzFeed News. "We are still unwilling to spend the kind of money that would be needed."