“As a general rule it’s not a crime for a removable alien to remain in the U.S,” says Jose Antonio Vargas, reading from Justice Anthony Kennedy’s brief on the recent Supreme Court decision on immigration. "When I saw that I was like, ‘Okay, well, I guess that means that I’m no longer illegal.”

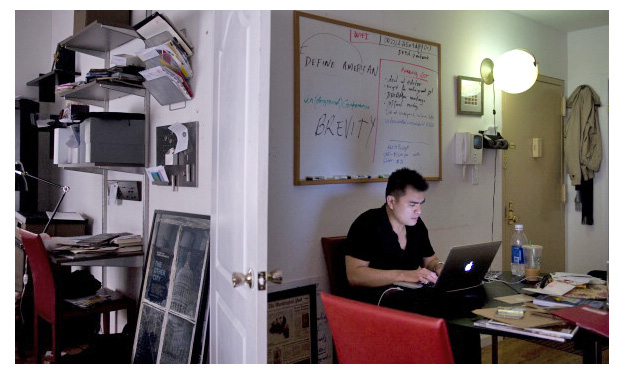

Vargas is sitting in a small apartment, right off Manhattan's Union Square. The Supreme Court brief is not just a matter of legal theory or political implications for the 31-year-old journalist. Over the past year he’s spent many days in his second floor walk-up, always aware that any moment he might hear a knock on the door that meant federal agents had arrived to deport him.

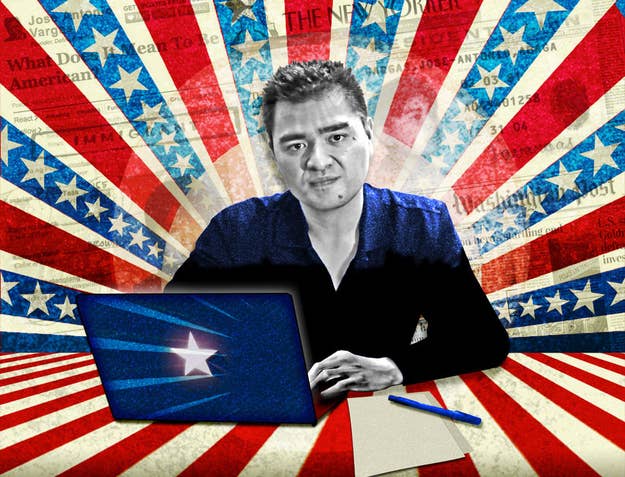

It’s been exactly 372 days since Vargas revealed, in a New York Times Magazine cover story, that he was an undocumented worker. An undocumented reporter, no less, who’d won a Pulitzer Prize and written for the country’s most esteemed publications, like The Washington Post and The New Yorker.

The story was a massive hit: “undocumented immigrant” trended worldwide on Twitter; it was the most-read story on Google News for two weeks; tens of thousands shared it on Facebook.

Overnight, Vargas became one of the most public faces for the approximately 11.5 million undocumented immigrants in the country and the network of tens of millions more who support them. And though he was often mistaken for a Latino, he was actually from the Philippines — and a college-educated gay man, who'd come to the U.S. on a plane — challenging notions about what undocumented immigrants look like.

But there was a very big downside as well. In the aftermath of the bombshell piece, Washington State revoked his driver’s license. An online petition popped up, demanding he be deported, and he received threats. He also received a torrent of scathing criticism from his peers in journalism, questioning his character and his motives. Some at the Washington Post, which had originally killed the story, began a whisper campaign against him, suggesting he couldn’t be trusted. He lost a number of friends and colleagues, including some he'd looked up to and admired.

Although Vargas has written about his experience as an undocumented worker, he’s been reluctant to publicly talk about the impact his decision had on his place in the media world, the fallout from his controversial move, and how he’d been treated by fellow members of the press. In an extensive interview with BuzzFeed, he agreed to open up about these issues for the first time—from the surprising support from high profile fans like Mark Zuckerberg, Sheryl Sandberg, and yes, Aaron Sorkin—to what his friends say he viewed as a betrayal from the Washington Post, a newspaper that he called his home for five years.

The curtains are usually closed at his apartment in Union Square. There is a kitchen table, which wobbles unevenly, and a coffee table and sofa, both places he uses as work stations for his MacBook Air while listening to Beyonce on his stereo. He likes it noisy when he writes, the volume up. His apartment barely avoids feeling cramped. There are stacks of books—Joan Didion, Katherine Boo, Gore Vidal. A collection of West Wing DVDs, the boxed set; a globe hangs over the door, a reminder of all the places he can’t go without legal papers, he says.

There’s also quote from James Baldwin (and a photograph) hanging on the wall. “Our history is each other. That is our only guide.” Baldwin is Vargas’s spiritual ancestor—a gay black man, writing in a time, Vargas points out, when America could just barely deal with him being black.

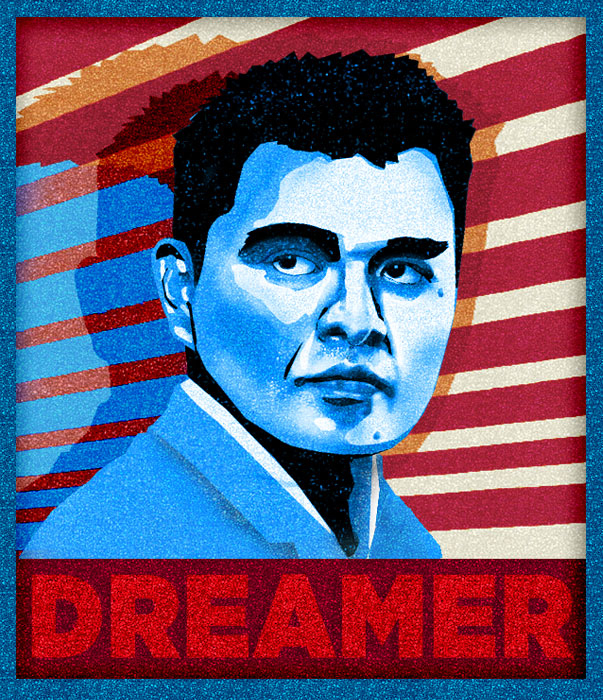

On the table, is a copy of Time magazine, the June 25, 2012 edition. On the cover is a picture of Jose, surrounded by more than 30 others, popularly known as “Dreamers” — immigrants who came over to the country at a young age illegally but consider the United States home. As immigration becomes one of the crucial issues of the 2012 campaign, the Dreamers, and their immigration rights advocates, have taken on an increasingly influential role in the debate. Within one year, says, “We went from the New York Times debate asking if I was an outlaw, to a Time cover, with all of us, calling us Americans.”

The same week of the Time story, President Obama announced sort of temporary reprieve for the Dreamers, which will likely allow some 300,000 to 800,000 immigrants who fit the criteria to stay in the country. However, the cut off age for the new program is 30 — meaning at 31, Vargas's legal status remains in limbo.

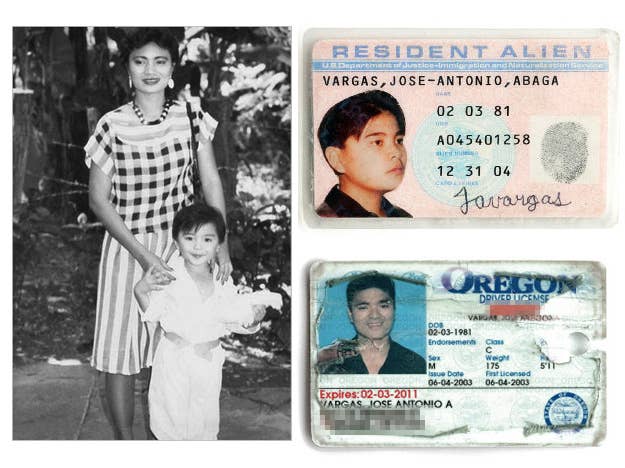

Vargas was born in the Philippines in 1981. In 1993, his mother sent him to live with his grandparents in the Bay Area. After a DMV worker told him his documents were fake when he tried to get his drivers' license, he learned he was here illegally. He decided, with his grandparents, to keep it a secret, confiding only in a few trusted teachers at school.

At 19, he got his first job at the San Franciso Chronicle, and it was in the journalism he would find his identity. He was picked up by the Washington Post in 2003, and was tagged as a rising star: during the 2008 election, the Post assigned Vargas to one of the most coveted and prestigious gigs in journalism, the campaign beat. Before he left for the road, legendary Post journalist David Broder advised him to read Boys on the Bus, the classic account of the 1972 press corps. “I mean, it was hilarious—like, oh god, nothing has changed—it is mostly still boys on the bus, mostly,” he recalls.

But he didn't quite fit in. To colleagues on the bus, he seemed obviously talented, but at the same time standoffish and tightly wound. “It was so weird, man,” he says. “I mean, I don’t know if you remember how I was. But I was just so, like…This fear of getting found out… It was so surreal.” (I met Vargas for the first time in 2008 on the campaign trail.) If he did at times come off as abrasive, he now thinks it had to do with what he was hiding: the stress of keeping a secret that he feared was more likely to be revealed the more prominent he became.

At one campaign stop in Texas, he was pulled over by a Texas sheriff for speeding—he thought the cop was going to make him call The Post to explain that he actually was a reporter on assignment. He was certain that his status wouldn’t remain a secret much longer. At an event in Iowa, he got into a foreign policy debate with a voter—when the voter asked where he was from, Vargas shut down—he hated to discuss his personal life and family. Covering another campaign rally where the late Ted Kennedy—an immigration advocate—was set to speak, he seriously considered outing himself to the senator, in hopes Kennedy might be able to help him. “I was surprised, I was so surprised I made it as far as I did and didn’t just blurt it out. There were so many moments,” he says.

The next year, he decided to leave the Washington Post for the Huffington Post. His work on a series of stories about the Virginia Tech shooting had helped him and the paper win a Pulitzer—he’d found many of his sources for that story by using Facebook, adopting social networking platform that some of his co-workers had barely heard of. He wanted to get closer to the cutting edge of journalism, he says. “Arianna offered me a job, and you know, no one really refuses Arianna Huffington—she’s just so amazingly charming—and I really wanted to know about, I wanted to learn about SEO, and I wanted to learn about the web, right? This was summer of ’09. This was before any…you know, before mainstream traditional people started leaving the New York Times and going to the Huffington Post.”

The Washington Post urged him to stay—executive editor Marcus Brauchli invited him to a breakfast meeting, pitching the benefits of the paper, and telling him not to leave. The hard sell failed. The Post, under Brauchli’s reign, was beginning a period of hemorrhaging its star reporters, including the late Anthony Shadid, Bart Gellman, Robin Givhan, and Howard Kurtz, as local magazine The Washingtonian would point out under the headline: "Marcus Brauchli Is Sinking the Washington Post.") Losing someone from a younger generation of reporters to an online site, in the midst of the Post's collapsing ad revenues and dying readership, was another blow.

In the summer of 2010, while still a contributing editor to HuffPo, Vargas landed what would turn out to be his biggest story yet: a series of exclusive interviews with Mark Zuckerberg, the founder of Facebook. He'd gotten to know the Facebook team with his Huffington Post tech coverage. The movie The Social Network was about to come out, and the social media company was worried the film wouldn’t depict Zuckerberg accurately — or, more to the point, in a favorable light. Vargas reached out to Facebook for an interview with Zuckerberg; Facebook accepted.

Vargas emailed David Remnick, editor of the New Yorker, asking if the magazine would be interested in a Zuckerberg profile. Remnick said yes — Facebook had just turned down another New Yorker writer’s request for an interview, according to sources familiar with the situation. The subsequent piece on the young entrepreneur hit at exactly the right time, the month before "The Social Network" opened, sparking a nationwide debate about Facebook and its founder.

For Vargas, getting published in the New Yorker felt like reaching the pinnacle of journalism. “I literally learned how to write by reading and memorizing the New Yorker,” he says. “That’s how I learned how to write. That’s how I learned how to use semicolons, because of the New Yorker — you know, just like, encountering them there. I remember looking at them and going, what is this, a comma missing a period?” When the story hit, he was flooded with book and magazine offers. “Look, getting published in the New Yorker. I didn’t really realize what a big deal that was. Huge deal. Publishers were like where’s your book, where’s your book. And then I was going to do a book, and I realized: My first book can’t be on Zuckerberg. You know? Like, if I’m going to do a book, here’s what I need to do—this is what I need to come to grips with.”

After the Zuckerberg profile came out, Vargas went into a kind of hiding in his Union Square apartment. He remembers lying on the couch for about two weeks, stuffing his face with junk food, watching re-runs of The West Wing, depressed at time he should have felt triumphant. After years of living on the edge, the pressure of his secret had taken its toll. The fear was “debilitating,” he remembers. “As a journalist, I was mortified, and I kept thinking: What would Don Graham say, what would Arianna Huffington say? I lied to them. I felt so bad about that. And not just that—what would happen to my family? So the fear was really tremendous.” Though his grandfather had passed away, his grandmother was 76 years old—he was worried she could be drawn into the controversy, or get in trouble for sheltering him all these years.

In December, he met with a close friend over dinner in his apartment, Jehmu Greene, an experienced social activist and former president of Rock the Vote. He told her he was going to come out. A few days later, he told Jake Brewer, a tech entrepreneur, and then Alicia Menendez, a young Hispanic political commentator. They developed an ambitious plan: start an organization for so-called Dreamers like Vargas to change the immigration conversation in America. It would start with his confession.

By June of 2011, Vargas had been working on writing his personal story with two editors from the Washington Post, Ann Gerhart and Carlos Lozada, for months. Though he was a freelance writer at the time and still a contributor to The Huffington Post, Vargas says he felt a debt of loyalty to the Post—the place that had given him his professional identity, and believed the story should be published there. He went through eight drafts.

A few days before the story was set to publish, Lozada called Jose and told him the paper had killed it. The decision, Vargas learned, came from executive editor Marcus Brauchli. Vargas called Brauchli to discuss—the editor told him that he was “free to take the piece” elsewhere.

Later, the Post would say that Vargas hadn’t told them soon enough about a second driver’s license (from Washington State) that he'd attained illegally. But it was Vargas himself, he says, who told the paper about the license's existence. “I remember coming to Carlos literally with my passport—with all of my stuff—and my lawyers had advised me to not tell the Washington Post that I had already…that I had also had had to procure a second driver’s license. And I remember calling Carlos about this and saying, ‘hey, I have this second driver’s license.’ And Carlos was like, ‘Oh, we need to put that in.’ ‘My lawyer doesn’t want me to.’ ‘We need to put it in.’ So we put it in.” Getting a fake driver's license was one of the ways he'd survived as an undocumented world. However, that detail apparently spooked Brauchli, who became fearful of getting involved in a controversy, according to sources at the paper. (A year earlier, Brauchli also chose to accept the resignation of another young political reporter at the Post, Dave Weigel, after snide emails he'd written to a private listserv were leaked to a conservative website.)

The Post’s decision left Vargas feeling deeply disappointed. “It was really hurtful,” he says, choosing his words carefully. “It was really hurtful. I love the Washington Post. I will always love the Washington Post. It was my home, I slept there sometimes. It gave me my identity.” Vargas believes that another reason was how sensitive the immigration topic had become. “The way Marcus…the way the top editors reacted to it is emblematic of in some ways how journalists, how, largely, journalists think about this issue. You know, it’s like a hands-off, 'I don’t know what to do with that,' you know? And maybe some of it was like, 'we can’t believe he was here.' I was one of them. Right? And now I wasn’t.”

Almost immediately however, Vargas found a home for the story at the New York Times Magazine. The magazine closed and printed the story within the week, having found no issues with its reporting at all.

***

The reaction to Vargas’s article was largely supportive. Other undocumented workers reached out to him and joined the newly founded Define American. However, the industry’s media critics—a group largely made up of older white males—found the young reporter suspicious.

The Washington Post ombudsman, quoting anonymous colleagues, wrote that

Vargas was a “self-promoter” who "many colleagues didn't trust" and needed "constant watching.” Oddly, despite that shot at his character, the Post story concluded that Brauchli shouldn't have killed the piece. Jack Shafer, who at the time was the media critic at Slate (also owned by the Washington Post company) went even further, calling Vargas a liar whose credibility would be forever damaged. Shafer compared him to a young black woman at the Post, Janet Cooke, who notoriously fabricated a character in a story in 1980.

Although neither Shafer nor the Washington Post was — or is — able to point to any inaccuracies or ethical issues with Vargas’s work, the media watchdogs didn’t stop from casting aspersions on Vargas’s character. When asked by BuzzFeed if his views on Vargas had changed, one year later in light of the fact that Vargas’s work has held up under scrutiny, Shafer said he’s still “skittish about him.”

In response to queries from BuzzFeed, a Washington Post spokesperson defended Brauchli’s decision, saying the paper was “entirely confident we made the right decisions for the right reasons.”

Vargas wanted to respond to the attacks—instead, though, he listened to the advice of friends who told him to hold his fire--getting caught up in a mud fight with media critics would be a distraction to his larger message. “I knew that somebody was gonna say, ‘Oh my god, he lied.’ But I was kind of hoping that they would say that and then they would move to the second…you know, that would be the lede—‘He lied!’ The second paragraph? “Why did he lie?” I was kind of hoping that we would get to the second paragraph so then it stops becoming about me and it would be about, like, wait, how many Jose Vargases are out in this country of ours going to school with us, working with us, living with us, and us not even knowing. I was kind of hoping that it would move there. To some extent, it did.”

He did get support from people in high—and unexpected—places. Aaron Sorkin, screenwriter of The Social Network and The Newsroom, read that Washington State was revoking Vargas’s driver’s license. He contacted Jose personally and offered him his car service anytime he wanted. Jose’s friendship led to his drafting a memo about immigration reform for Sorkin, which worked its way into the plot of the second episode of The Newsroom. And, in a moment of life imitating art, Will McAvoy—Sorkin's fictional cable news host—offers his own car service to a undocumented worker.

***

Vargas’s first run in with his old colleagues was at a Mitt Romney campaign event in Iowa. For the first time in his life he was going to a rally with a sign rather than a notepad. The sign said: I AM AN AMERICAN W/O PAPERS. Just four years earlier, he’d been at dozens of these events, a member of the press corps in good standing — he’s travelled to the 99 counties in Iowa. Now, the press was watching — and judging—him.

A reporter who he’d interned with at the Post gave him “‘What are you doing,’ kind of look,” he says. One of his former colleagues texted him: “why are pulling this stunt.,” The Romney campaign spotted him, and a woman from the campaign tried to block him from asking a question, and his sign from the cameras.

Holding up a sign, Vargas admits, was outside of his comfort zone. He prefered a pen and pad, or a camera, to a sign. A few months later, however, he’d find it again when he started reporting the cover story for Time magazine in March. “That’s when I felt like, okay, this is my role. Reporting is my religion. I covered cops, I covered school board meetings, city hall—whatever. And I actually think it’s better for journalists—it’s better for us to be much more transparent about where we stand. You know…being gay is not a political issue. I’m gay. Okay. It’s not a left or right thing. It’s like just because I’m gay automatically means that I’m this or that. Just because I’m undocumented it automatically means that I’m this and I’m that. In some ways, the media has done that—they’ve boxed us in. And in country—and here’s my question to journalists everywhere—in a country that’s going to get gayer, browner, more Asian, more women in power, how are we going to accurately reflect the different realities that are out there?”

Time editor Richard Stengel had assigned him the story, and in his editor's note, Stengel wrote that he "applaud[ed] his willingness to put his beliefs on the line...He was an American in all but name." The piece appeared the same week President Obama decided to offer temporary reprieve for the Dreamers—the men and women, under the age of 30, who came to America at a young age. The story got very public support from some of the most influential people in the country—Sheryl Sandberg, COO of Facebook, posted a paragraph on her page in support of Vargas. Mark Zuckerberg “liked” it.

The Time story brought him face to face with some hostile political opponents. He argued with Fox News host Bill O’Reilly—in the end, the talk show host agreed that Jose should be allowed to stay in the country. "I agree with you. I think there should be a pathway for you," O'Reilly told him. "However, however. If you're 32, Jose, and you sneak across the border. No. I'm telling you, 'No.'" In an even more contentious interview last month with Lou Dobbs, the man who’d made a career attacking immigration also conceded that Jose should stay. Though Dobbs called him "a partisan illegal immigrant," he was even was asked back on the show.

“I entered the workforce, and I lied to enter the workforce," Vargas says, a line he uses to begin most interviews. "And if I don’t acknowledge the fact that I lied, and the fact that I am sorry, then I’m not going to get anywhere. I’m not going get anywhere in having conversations with Bill O’Reilly, for example. But then after I say that I’m sorry that I had to lie, then I have to explain to you what put me in those situations that I had to lie. What would you have done if you were in the same situation?”

Vargas’s next step is a book he’s working on about his life as undocumented worker, along with a documentary about the past year. His campaign—based, fundamentally, in the influence of his own writing and reportage—has had effects on the debate. (Huffington Post and NPR, for instance, nor longer use the phrase “illegal immigrant. The Times and Post still do.) Ironically, he can still get paid for his writing assignments at Time magazine and other places — though he can't be employed, he can work as a private contractor — and he’s about to start to hiring his own employees for Define American.

On a personal level, Vargas, according his friends, has changed. The wound-up and overly ambitious kid on the campaign trail has been transformed. He didn't need to be on the bus this election cycle. "He was clearly dealing with a really big secret,” says Jehmu Green, a co-founder of Define American. “Coming out for the second time in his life has allowed him to be his true self.”