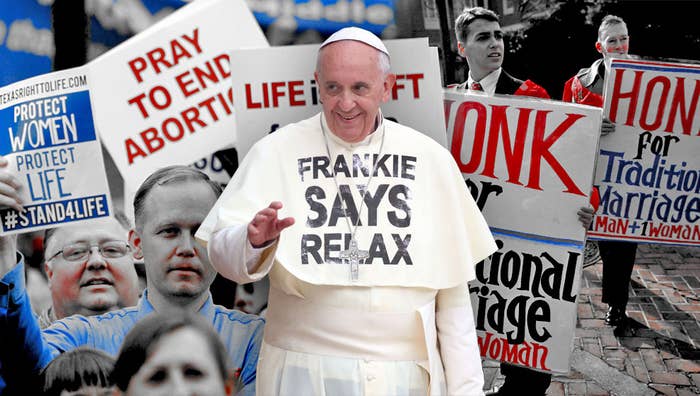

WASHINGTON — As political spectators gawk at the "civil war" currently engulfing congressional Republicans in the wake of the government shutdown, a potentially more consequential rift is beginning to form within the party's traditional coalition of conservative Christian value voters. Blame the Vicar of Christ.

In a series of interviews earlier this year, Pope Francis repeatedly signaled a desire for his flock to disengage from the culture wars — complaining that the church had become "obsessed" with issues like marriage and abortion, actively seeking common ground with atheists, and even appearing to flirt with moral relativism. While the new tone coming out of the Vatican has drawn plaudits from progressives, it has also driven a wedge into the powerful political alliance between conservative Catholics and evangelical Christians that's been instrumental in electing hundreds of Republicans over the past four decades.

Bryan Fischer, a senior analyst at the American Family Association and devout Christian, said he was "disappointed and alarmed at some of the things the pope said" — a sentiment shared by many of the protestant culture warriors on America's religious right.

"It raises questions in our mind because the Catholic Church has always been a faithful shoulder-to-shoulder ally to social conservatives in the fight to protect unborn human life" and the sanctity of marriage, Fischer said. "We simply have questions of whether we'll be able to count on the Catholic Church to be comrades-in-arms to continue to fight these battles."

Russell Moore, president of the Southern Baptist Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission, struggled to find theological justification for the pope's comments. In a column earlier this month, he concluded that Francis was guilty of "severing the love of God from the holiness of God" — even as he mused that he was not interested in "refighting the Protestant Reformation."

And when Francis seemed to suggest that salvation was possible for atheists as long as they lived moral lives, Christian Broadcasting Network reporter David Brody tweeted, "Say what? Catholics please explain this... Evangelicals are NOT kosher with this."

From the start of their unlikely alliance, Catholics and evangelicals have always made for strange bedfellows. Before the 1970s, American protestants and Roman Catholics had been locked in a religious rivalry that sometimes expressed itself in nuanced theological debates and just as often devolved into pulpit-pounding sermons rife with fire and brimstone. Considerable swaths of each faith were convinced the other side was going to hell.

It wasn't until the Supreme Court's Roe v. Wade decision — and the sexual revolution that presaged it — that the two religions were united in an awkward but enduring marriage of convenience. For the better part of 40 years, evangelicals and Catholics stood side by side battling the encroachment of secularism, the collapse of traditional sexual ethics, and the general rot of American culture. When Jerry Falwell formed the Moral Majority, he insisted that Catholics be among the leadership. And the coalition only became more focused and influential after the Soviet Union collapsed, when politically minded priests in the U.S. who had spent much of their energy railing against the evils of communism shifted their homilies to pro-life commentary.

Their combined political influence became a driving force in the Republican Party, forming a movement that launched a thousand HBO boycotts and helped elect George W. Bush. Then Pope Francis came along.

To be clear, conservative Catholics in the U.S. are not exactly laying down their weapons of culture war and withdrawing from the battle en masse. They believe the secular media have blown the pope's recent remarks out of proportion, and they note that the church's doctrine has not changed. Matt Smith, president of the conservative organization Catholic Advocate, said there is nothing new in what Francis has been saying. "It's hate the sin, love the sinner," he said. "He's encouraging folks to make sure that we're still loving the person. In no shape or form is he endorsing same-sex marriage."

But Francis' approach has managed to resurface evangelical activists' long-held — and long-concealed — skepticism toward their Catholic peers. It's a dynamic that was on display earlier this month at the Values Voter Summit in Washington.

Asked if he was concerned that the new pope would lead Catholics away from political engagement on social issues, Family Research Council President Tony Perkins demurred: "I've only seen the articles. You cannot base a conclusion on one article, one statement, one speech. It's cumulative."

But then he offered what seemed like a veiled admonishment: "Those that subscribe to Biblical orthodoxy know what the teachings are when it comes to sexual morality. You can't change that unless you ignore or change the word of God."

Meanwhile, away from the gaggle of reporters, Tracy Pyland, a born-again Christian and Maryland mother of five who came to the conference with her husband and two youngest children, was less diplomatic when asked about the pope's recent comments.

"That's infuriating. That man needs to read his Bible," she said.

She hastened to add, "I don't mean any disrespect, but that man garners a lot respect and he should earn that respect. He should not have done that... He's not doing the job he was given, which is to represent Christ in a positive light."

With reporting from James Arkin.