In the gaming industry, getting a big hit is an incredible lucky break — but getting a second one makes you a god.

Every few years, a game company produces a single major hit that launches it into the stratosphere. In 2009, Zynga released FarmVille, a game that produced so much money that an entire massive gaming company was built around it. After that it was Draw Something, which turned the otherwise desperate OMGPOP into an overnight sensation that sold for $210 million to Zynga in 2012. And also beginning in 2012, it was King's Candy Crush Saga, which went on to arguably become the most popular mobile game of all time, bringing in billions of dollars for its parent company.

Yet none of those three companies have a follow-up to show, and indeed, not many game companies, mobile or traditional, do. Those that have are essentially legends: Valve, with Counter Strike and Half Life 2, along with a number of other games; Blizzard, with World of Warcraft and Starcraft 2; studios owned by larger companies like Naughty Dog, with the Uncharted Series, and BioWare with its Mass Effect games. Among all of them are two common traits: They, at least for the time being, are robust businesses, and they produce expensive games that require a larger ensemble team spanning artists, creative designers, engineers, and acting talent.

But what would it take for a mobile company like Zynga, OMGPOP, or King to actually be able to not only survive, but thrive as a large publicly traded company?

The problem for the Zyngas, Kings, and other mobile gaming companies is that the technical barriers for their kinds of games that used to exist simply do not anymore. The next hit can come out of nowhere, from a single person, and blow more pedigreed games off the App Store charts: Flappy Bird went from completely nonexistent to dominating the Apple App Store, and made its owner what was reported to be hundreds of thousands of dollars in advertising revenue the month that it was live.

The financial edge more modern mobile gaming companies had is beginning to wane. With the emergence of Facebook's mobile app install ads, targeting for app installs gets better and better every day, giving a smaller team a better chance of finding the right group of gamers to install the game and then spread it to their friends. (Think games like the tile-matching game like 2048, Dots, Flappy Bird, and the quiz game QuizUp.)

And this trend may eventually even extend to AAA studios. One of the most important edges that companies like Activision and Electronic Arts have enjoyed — the ability to pay the immense upfront cost for a technically demanding game — is starting to taper off thanks to cheap development technologies like Unity. When asked by BuzzFeed at a panel last week, Unity CEO David Helgason said the company is "pretty damn close" to having the technology to allow a few designers in a garage to essentially create a game like Bioshock Infinite.

For a higher-end studio, which requires a mixture of creative artists, engineers, designers, and a staff with the business wherewithal to keep the company running, amassing talent makes a bit more sense. After all, Bioshock Infinite isn't Bioshock Infinite without its beautiful art direction and deep storytelling.

But with the difficulty and costs of producing even technically demanding games dropping like a rock, it's a better time than ever for an independent developer to set off and try to build the next major game. Of course, it isn't easy— in fact, most games, like most startups, will fail — but the possibility exists today that didn't exist five years ago.

And outcomes abound for developers beyond building a giant gaming company and trying to take it public. The most obvious pathway would be to do what Mojang, the creator of Minecraft, has done: build a killer game and quietly make an enormous amount of money with a small team, leading to huge profit margins for the company. That money could be reinvested in a new game, or paid out as a huge dividend to employees for their hard work — and in that case, the developers could even make more than they would through an outright exit.

Alternatively, companies can go the route of Supercell, which basically sold half its company in a financing deal where the company raised $1 billion from Softbank. This is more of a direct obvious exit for founders and the company, and then gives a company with a large platform — in this case, a telecommunications provider — access to the IP to better sell products.

But if King's public debut was any kind of indication, going public with a single hit — even if it is the most popular game of all time — does not bode well for the purposes of building a long-lasting company.

Ironically, one of the most successful gaming companies of all time was actually a hardware company. Nintendo has produced games that are beloved by gamers — and still does today — but those games are built solely for its platforms like the Wii and the Nintendo 3DS. That Nintendo is beginning to falter is not a sign that it is no longer making good games, but rather that it can't produce hardware that can compete with companies like Apple.

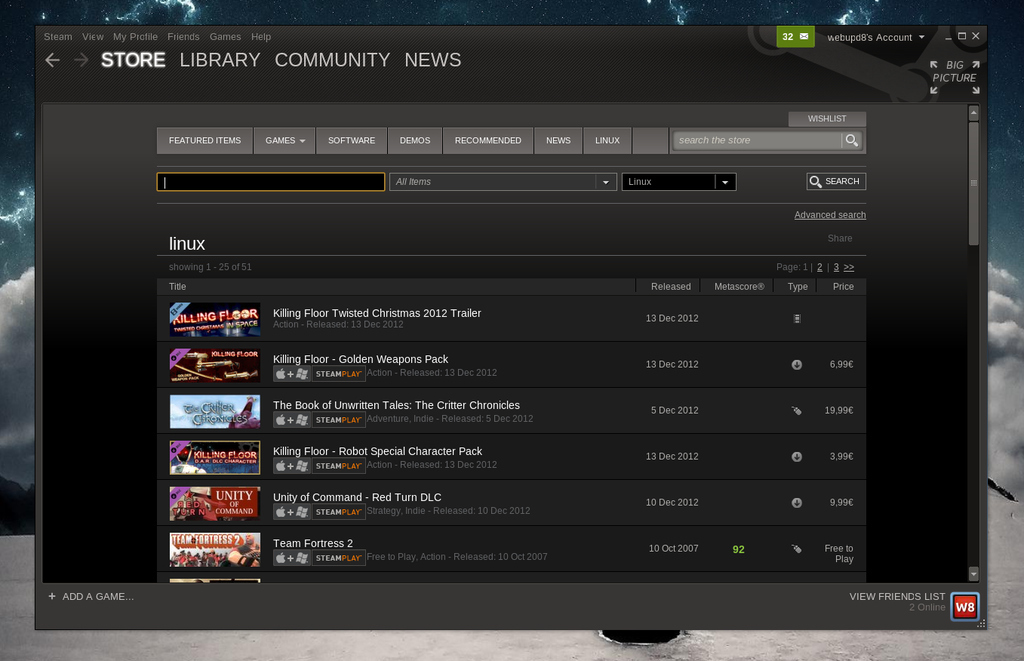

And then there's Valve, which otherwise looks like a highly successful company but is in fact a company built around the largest distribution platform for PC games in the world. If a developer plans to make a game for the PC, it is basically required to go through its Steam distribution service. Small wonder that other gaming publishers like Electronic Arts and Ubisoft are clamoring to build their own platforms like Origin and Uplay, because if either falters on a hit, it's essentially game over in the eyes of investors. Even Zynga attempted to build its own platform independent of Facebook.

And perhaps that is what the mobile gaming industry will look like in the future — a series of platforms like Steam and Softbank that creatives can lean on for exposure and marketing for a share of the success of a game. But in 2014, being a successful game developer — even a team — doesn't seem to require having a massive exit with an initial public offering. Building a fantastic game that makes its creators a ton of money seems more than good enough.