This bewilderingly large graphic is part of Goldman Sachs's defense against a four year-old gender discrimination suit that gained new steam as the plaintiffs sought to include up to 2,300 current and former female employees in a class action.

The plaintiffs said in a filing earlier this month said Goldman's "common, discriminatory performance review, compensation, and promotion procedures … cause systemic disparate treatment against women" was in violation of federal and New York City anti-discrimination laws. They also repeated allegations that Goldman Sachs bad a "boys club" atmosphere, including trips to strip clubs and excluding female employees from golf game and trading-floor push up competitions.

The plaintiffs pointed to statistics gleaned from Goldman Sachs data gathered during the discovery process and analyzed by an expert witness which showed that female vice presidents earned 21% less than their male counterparts, while female associates earned 8% less and that 23% fewer vice presidents who were women earned promotions to managing director. The plaintiffs will respond Tuesday, a lawyer for the plaintiffs told the Wall Street Journal.

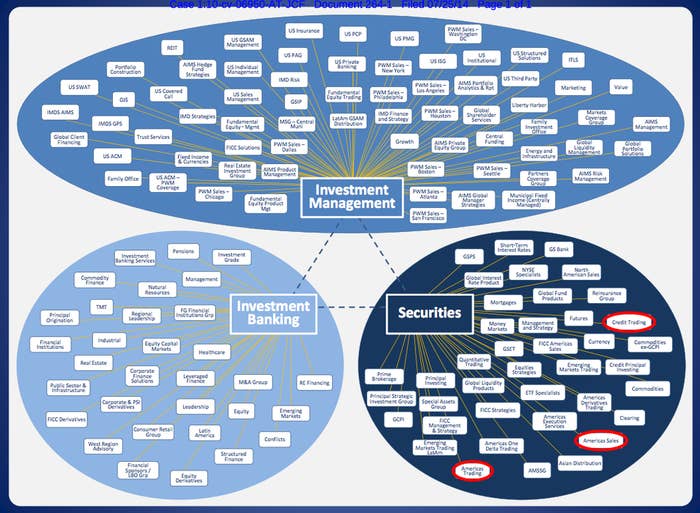

In a filing today, Goldman's lawyers sought to rebut the plaintiffs' attempt to certify the class-action, saying that the experiences of the women named in the suit were not indicative of a pay and promotion policy that goes across the entire proposed class, which would include female associates and vice presidents in the bank's investment banking, investment management, and securities divisions from 2004 through today. The company's lawyers cited the precedent the Supreme Court established in Wal-Mart v Dukes, where the Court refused to certify a group of female Wal-Mart employees as a class because they couldn't show that a common corporate policy lead to differences in pay.

"What Plaintiffs must show to certify their proposed class is not merely the existence of some procedural framework, but that the Firm's undeniably gender-neutral processes have been uniformly applied—across a class of more than 2,300 women professionals in 140 Business Units—to disparately impact those professionals," the bank's lawyers said in the filing.

The filing included a diagram showing the company's business units in far more detail than is typically included in the bank's public reports. David Wells, a Goldman Sachs spokesperson, said the that the organization chart included in the filing wasn't current, but instead accurate through 2011. Even so, it provides a stark visual look at just how sprawling and diverse Goldman Sachs's business is.

To rebut the plaintiffs claims that the female employees in the investment banking, investment management, and securities divisions were affected in a discriminatory way by a common policy, Goldman pointed to the diversity of business units and compensation policies in those units. "This case is a textbook example of why class certification requires proof, not a broad brush and a bucket of mud," the lawyers said in a filing.

Investment management includes both wealth management for wealthy individuals, foundations, and endowments along with funds run by the bank for investors. Securities includes selling and trading all sorts of financial products, like stocks, options, bonds, mortgages, currencies and commodities, while investment banking includes advice for companies on strategic matters like fundraising and mergers along developing and selling financial products to companies.

Goldman Sachs also has an investment and lending division — whose female employees the plaintiffs in this case did not try to represent in their suit — that makes longer term investments in companies, debt, and real estate.

Two of the original plaintiffs worked in the securities division of the bank, which itself had 35 different business units in 2005 when one of the plaintiffs, Cristina Chen-Oster, left the bank.

Goldman said that the diversity of the investment banking, securities, and investment management business and the purported lack of evidence of discriminatory polices across the three divisions and their more than 140 business units is a reason not to certify a glass of female employees. "Across these Business Units, the proposed class members advised on mergers and acquisitions in the healthcare industry, traded petroleum futures, structured financial derivatives, ran investment funds based on mathematical algorithms, and so on," Goldman's lawyers said in a filing.

The lawyers said that "nothing about the diverse roles of these professionals...is uniform." The pay structure is similarly differentiated — while employees across Goldman get a base salary and a bonus, each business unit has its own bonus policy.

Commodities traders, for instance, have their pay "tied directly to their profit and loss statistics," Goldman's lawyers said, while managers in the Principal Strategic Investments Group, which owns stakes in market-related companies like exchanges, "do not analyze profit and loss on an individual level in determining compensation."

Goldman also provided its own expert witness that criticized the plaintiffs' analysis, saying it didn't take into account how the performance of employees affected their pay and promotion. The filing also characterized additional declarations added to the suit— including one from a current Goldman Sachs employee — as "a handful of anecdotes of supposed hostility toward women" and said that the six declarations gathered over four years showed the evidence of discrimination was "less than paper-thin" and "virtually nonexistent."