Courts in more than two-thirds of Mexico’s 31 states have granted same-sex couples the right to marry over the past two years in a series of rulings that will likely make marriage equality a reality nationwide in the near future.

The wave of rulings throughout Mexico hasn’t caused the uproar that has followed rulings in the United States over the past year striking down state laws barring same-sex couples from marrying. Couples have not rushed to marry nor have conservatives organized major protests.

This is in part because the technicalities of Mexican law have meant these decisions have been much more narrow in their immediate impact. Each decision applies only to the individuals who have brought the cases, and other same-sex couples will still have to sue in order to marry. It takes multiple cases meeting certain technical requirements for the courts to nullify a state law in Mexico — a hurdle that has not yet been met.

But with new rulings being announced almost every week — judges in seven new states ruled in favor of marriage equality in the first three months of 2015 alone — it seems almost inevitable that this day is coming, say legal experts who have closely followed the litigation.

“It’s just a matter of time,” said Geraldina Gonzalez de la Vega, a lawyer who worked on the first of these suits filed in 2011 and is now a clerk to a Supreme Court minister. “This has spread all over the country.”

The first place in Mexico to allow same-sex couples to marry was Mexico City — a federal district that functions like a state, sort of like Washington D.C in the U.S. A marriage equality law was adopted by the city’s legislature at the very end of 2009. When opponents took the law to Mexico’s Supreme Court, the judges ruled that it was constitutional for Mexico City to recognize same-sex couples and went one step further: They also held that the city’s marriages were valid in every state of the country.

But the Supreme Court left state marriage codes restricting marriage to heterosexual couples in place. The first case to argue that state marriage laws restricting marriage to a man and a woman were also unconstitutional seemed like a long shot. Unlike in the United States, where legal activists spent years spelling out the grounds for marriage equality and some state challenges attracted A-list attorneys, the idea to challenge a state marriage code came from a law student in the largely rural state of Oaxaca.

Alex Alí Méndez Díaz has now been involved in lawsuits in 19 states even though he is still finishing advanced studies in Mexico City and has an unrelated full-time job. Méndez first thought about challenging state marriage laws when he met a couple named Alejandro and Guillermo while helping to plan a pride parade in his native state of Oaxaca in 2011. The two wanted to marry, but they couldn’t afford to make the trip to register their union in Mexico City.

“These guys said to me, ‘We want to get married but we don’t want to leave. ... Can we get married here in Oaxaca?'” Méndez recounted during a 2012 interview with this reporter in Oaxaca City. He downloaded the ruling in the Mexico City case and concluded that it laid the foundation for challenging Oaxaca’s marriage code.

Others in Oaxaca’s local LGBT rights organizations thought going to court was a bad idea, Méndez said, in part because they were worried that the state wasn’t ready for a public discussion about same-sex marriage. But he was sure of his legal arguments, so he decided to bring the case by himself.

“I said, ‘Fine, if the collective won’t do this as a group, well, I’m the only lawyer [in the organization]. I’ll do it,'” he said.

In August 2011, Mendez filed cases on behalf of Alejandro and Guillermo and another couple he recruited through Facebook. In early 2012, he filed one more. These were amparos, a kind of suit in the Mexican system concerning human rights violations. He lost two of them — including Alejandro and Guillermo’s — but the third, on behalf of a couple identified as Lizeth and Montserrat, eventually made its way to the Supreme Court. In December 2012 the Supreme Court sided with the couple.

“Like racial segregation, founded on the unacceptable idea of white supremacy, the exclusion of homosexual couples from marriage also is based on prejudice that historically has existed against homosexuals”

The written decision in the case, published in early 2013, made an impassioned argument for marriage equality. A unanimous opinion authored by Supreme Court Minister Arturo Zaldívar Lelo de Larrea said that the court needed to step in partly because of a provision added to the Mexican constitution in 2011 prohibiting discrimination on the basis of “sexual preferences.” Unlike in the U.S., Mexican courts recognize rulings from other countries, so Zaldívar also based the decision in part on landmark U.S. Supreme Court judgements striking down racial segregation.

“Like racial segregation, founded on the unacceptable idea of white supremacy, the exclusion of homosexual couples from marriage also is based on prejudice that historically has existed against homosexuals,” Zaldívar wrote, referring both to the 1954 school desegregation case Brown v. Board of Education and the 1967 case striking down laws banning interracial marriage, Loving v. Virginia.

The judgement allowed just the petitioners to marry — Mexican law requires essentially five identical rulings on a subject from a high-level court in order to establish precedent binding all government officials. But it provided a very clear blueprint for bringing more challenges. Méndez announced on Twitter less than a week after the decision was handed down in December in 2012 that he was preparing to file amparos on behalf of more couples in Oaxaca, and lawyers in several other states immediately began talking about copying the strategy.

“In the two years [since], we have succeeded in covering almost the entire country.”

Méndez also began working on an amparo colectivo, a petition of 39 individuals from Oaxaca challenging the marriage restriction. These actions didn’t revolve around specific couples alleging their rights had been violated because they’d been denied the right to marry. Instead, it was a group of gays and lesbians who said it was inherently discriminatory for the state to bar them from matrimony. This would streamline the process, allowing large numbers of couples to win marriage rights through a single suit, and also allow single people to win the right to marry even if they didn’t yet have a partner.

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of this amparo colectivo in April last year. Since then, groups numbering in the hundreds have successfully brought these suits in multiple states.

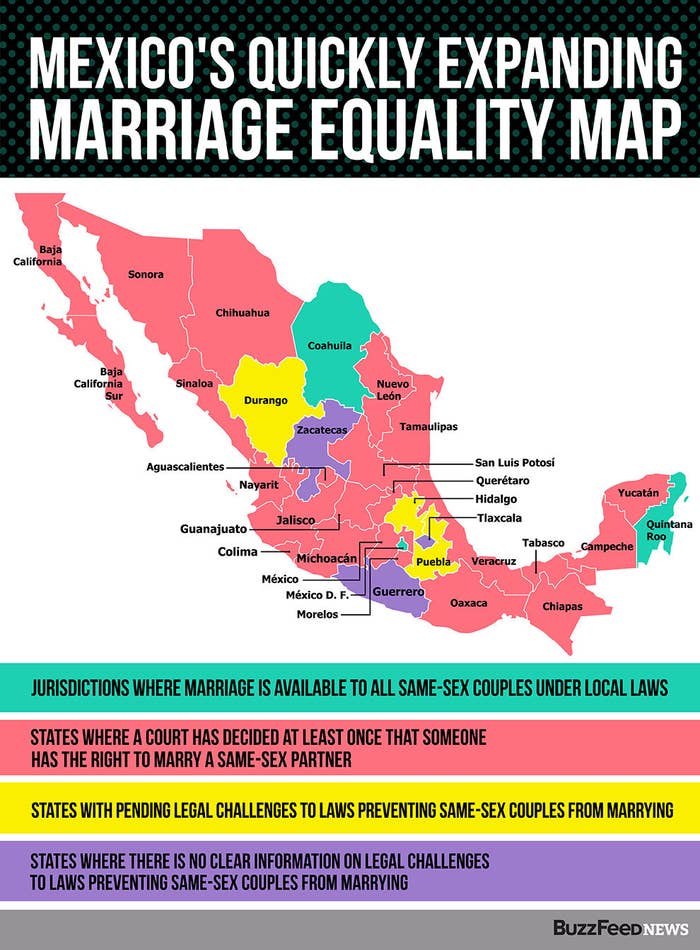

As of late February, there have been rulings in favor of marriage equality in 22 states, according to local news reports, and cases have been filed in at least four others. This legal wave nudged the legislature of one state on the U.S. border, Coahuila, to pass a marriage equality law in September. And the Caribbean state of Quintana Roo — where same-sex marriages actually began taking advantage in 2011 of the little-noticed fact that the wording of its marriage statute was actually gender-neutral — held two mass weddings of same-sex couples this year.

Méndez himself seems astonished at the pace of change.

“Imagine, in 2012, we won the first judgement in Oaxaca,” Méndez marveled during a phone interview last week. “In the two years [since], we have succeeded in covering almost the entire country.”

Even some LGBT rights supporters are a little mystified that marriage equality rulings haven’t sparked a national backlash. The fight over Mexico City’s 2009 marriage equality law brought strong opposition from the country’s Catholic hierarchy. Yet while some state bishops have condemned marriages between same-sex couples in the past few years, there has been no substantial opposition.

“The church was really concerned with the amendment here in Mexico City,” Geraldina Gonzalez de la Vega, the Supreme Court clerk who helped Méndez bring the Oaxaca case, said. But now, with scores of amparos pending, “they are not saying anything.”

Gonzalez attributes this in part to the fact that there isn’t much history of using the courts to force widespread change in Mexico, and so neither activists nor the media fully understand the scale of the change that’s underway. Méndez thinks this will change as the litigation moves from cases involving individual couples and produces the kind of rulings that will allow same-sex couples to marry in their states without having to file suit.

“The moment that there is an order from the Supreme Court forcing reform we’ll begin to see all kinds of resistance,” Méndez said. “We’re going to have serious problems with protests in opposition.”

Méndez expects the Supreme Court to start issuing the kinds of decisions that would make marriage widely available to same-sex couples throughout the country sometime in the next “two or three years,” based on the timeline for the cases already in the works. That may come sooner in some states — on Wednesday, the Supreme Court issued a ruling ordering the state of México (which borders Mexico City) to change its marriage codes, but it will take an additional case to make that binding precedent in the state. Three more states — Oaxaca, Jalisco, and Colima — are also on the verge of crossing that threshold.

As the wins become more substantial, advocates may no longer be able to carry on their work under the radar, and there are already signs that a backlash is coming. January brought the first high-profile resistance by local officials to a Supreme Court ruling allowing a couple to marry, a marriage equality standoff that made some national news. This came when the state of Baja California tried to duck a Supreme Court court order allowing a couple to wed in the city of Mexicali. The couple was turned away from city hall three times, the last of which after a volunteer who performs a mandatory pre-marital counseling session at city hall submitted a complaint saying the men “suffer from madness.” LGBT rights activists organized a protest in front of city hall under the hashtag #MisDerechosNoSonLocura (#MyRightsAreNotMadness), and city officials finally capitulated and allowed Víctor Fernando Urías Amparo and Víctor Manuel Aguirre Espinoza to marry on Jan. 17.

There are also signs that it could emerge as a theme in the campaign for national congressional elections that will be held in June, at least in some states. The clearest hints of this have come from Chihuahua, where Méndez said there have been 25 successful amparos. On Feb. 10, the leader of the opposition PAN party in the state legislature declared, “We are going to oppose approval of gay unions, we are going to vote against them, and that is what we were discussing with the bishop.”

But even if a backlash erupts now, Méndez said, the cases they’ve already won make marriage equality all but inevitable.

“Outside of Mexico, and even inside of Mexico, these advances are not widely known,” Méndez said. “It is very slow, it is very invisible — but it is irreversible.

Rex Wockner provided research assistance for this story.

This post has been updated to reflect a March 4 ruling against a law in the state of Chiapas banning same-sex couples from marrying