Sister Jeannine Gramick will be among the guests at a White House reception to welcome Pope Francis on Wednesday, an unexpected position for a woman who spent almost three decades fighting Vatican efforts to shut down her work ministering to LGBT Catholics.

In 1998, a years-long inquest into her work took such an ominous turn that she made a pilgrimage with her supervisor from the United States to the grave of their order’s founder in Munich. They planned to pray for a miracle to save Gramick from excommunication.

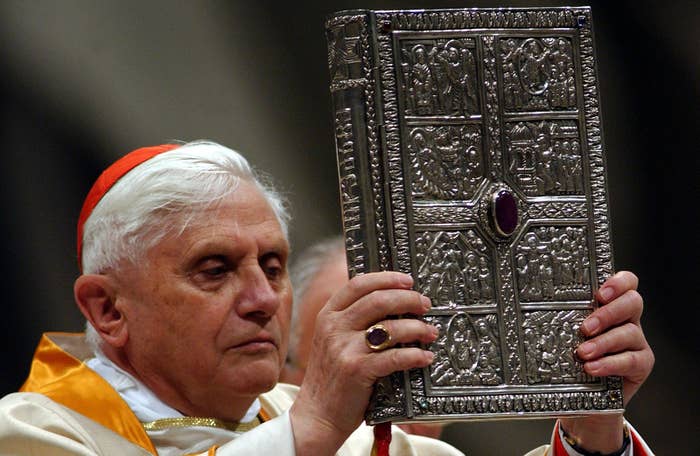

The Vatican’s top watchdog for doctrine — then Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, who would later become Pope Benedict XVI — had taken over the investigation into her ministry, accusing her of causing confusion about “the intrinsic evil of homosexual acts and the objective disorder of the homosexual inclination.”

The sisters were on the runway for a flight from Rome to Munich when Ratzinger himself boarded the plane. Gramick introduced herself when the flight attendants finished serving lunch, and he greeted her by saying, “I’ve known you for 20 years.”

He laughed when her supervisor explained she was afraid he would have her excommunicated, saying, “You can’t get excommunicated for what you think about homosexuality.” But a year later he issued an order forever barring Gramick “from any pastoral work involving homosexual persons.” She refused, and her order faced increasingly strident demands to close her down.

But those demands stopped when Pope Francis replaced Benedict in 2013. The Vatican even gave Gramick and a group of LGBT pilgrims she led to Rome in February VIP seats to Francis’s weekly audience.

“It was a great feeling of vindication, almost a euphoria that this is how the church should be,” Gramick told BuzzFeed News.

Gramick’s story is a parable about the life of progressives in the American Catholic Church after Vatican II. Vatican II threw open the doors of the church to the outside world that it had long viewed with suspicion and hostility. Progressives started many ministries with groups long turned away by the church, only to gradually see the opening shrink as the 21st century began.

They hear Francis promising a new opening, but the fact that her group is still having the doors of American churches slammed in their faces is a test of just how much of that promise will be fulfilled.

“It was a great feeling of vindication, almost a euphoria that this is how the church should be.”

Nothing in Gramick’s path to becoming a nun suggested she would become a church radical. In fact, as she describes it, it was her obedient nature as a child that first pulled her toward taking vows.

Born in a Polish Catholic family in northeast Philadelphia in 1942, her parents sent her to Catholic school. But she said her parents were “Catholic in name only” and never went to church. Her reverence for the nun who taught her in first and second grade — Sister Angela — first kindled her desire to become one herself.

“In hindsight, I think it was hero worship,” Gramick said during an interview in the house just across D.C.’s eastern border with Maryland that houses her group, New Ways Ministry. “In those days I believed everything that Sister said, and Sister was only saying what the priest was saying.”

She would go to mass every morning at 6:30, worrying her parents were going to hell because they never went to church. She could have chosen one of many orders when she finished school, but she chose to join the School Sisters of Notre Dame for no reason other than it was the order of her favorite high school teacher.

But this conservative trajectory brought her into the church during a period of its most radical transformation in modern history. She entered a convent in Baltimore in 1960, just after Pope John XXIII announced a great meeting of bishops would convene in 1962 to re-examine the church’s relationship to the wider world, which became known as Vatican II.

Gramick spent the years leading up to the meeting almost entirely cut off from the world. She hated appearing in public during her first year in the convent because of the full habits they had to wear, and she spent her second year cloistered and in silent contemplation for all but two short periods each day. But they were given books to read hashing out the major issues to be discussed at Vatican II — Could mass be celebrated in everyday languages instead of Latin? Could the Catholic church have a dialogue with other churches? — and they resonated deeply.

“Before Vatican II, the [church’s] mentality was the fortress mentality… that we have to be careful that we don’t get contaminated,” she said. “It tapped into something maybe I wasn't aware of: that we were meant to go out in the world.”

It took several years before the church’s new mindset significantly changed her day-to-day life. Like the sisters she idolized as a child, she became a teacher, and after a few years teaching prep school she decided to get a Ph.D. in mathematics to become a professor at the college run by the order, Notre Dame of Maryland.

Her life began to change in 1971, when she began her doctoral studies at the University of Pennsylvania. She was invited to a dance organized by a group formed in the wake of the 1969 Stonewall riots, the Gay Liberation Front. Their monthly dances were hosted by the campus’s Episcopal church, and the associate rector invited her to check it out.

“It’s like having a cocktail party for a group of alcoholics!” she initially exclaimed. But he could tell she was curious and ultimately convinced her to come under the guise of selling Coca-Cola at the concession stand.

That’s where she first met a man named Dominic Bash, whom she would get to know a few weeks later at an interfaith service organized with an Episcopal priest. He had been raised Catholic and had entered the Franciscan order, but he left the brotherhood early because he worried being gay would make it impossible for him to be a priest. He became a hairdresser and wound up going to the Episcopalian church because, Gramick said, he “had been thrown out of the confessional one too many times.”

She said he got tired of hearing essentially the same message from priests: “If you don’t stop [having sex with men] you’re going to go to hell.” Bash found fellowship in the Episcopal Church, but he told her he remained a “Roman at heart” and asked her if she would organize services with some of his friends in their homes. She agreed without hesitating.

“To me, it wasn’t edgy” to hold services like this, she said, which became known as the “home liturgy group.” She couldn’t see any reason their being gay should keep them from participating in church rituals.

“My idea was: This is their church and they have a right to the sacraments of their church,” she said.

They began holding home religious services weekly for groups of six to eight. She became close with Bash — who died of AIDS in 1993 — and he would come to the community of nuns where she lived to do the sisters’ hair. And he took her to bars to build up their little group, where she was often the only woman.

“I love to dance, so it was fun, and then they find out you’re a nun and you get lots of people who want to talk to you,” she laughed. But underneath, she said, “I felt like a missionary. We’d find the Catholics and I would have my Catholic conversation and tell them why they should come back to church: This is your church — don’t let other people screen you out.”

These bar nights led to the first complaints about her work. After she’d moved back to Baltimore in 1973 to teach at Notre Dame of Maryland, she would distribute fliers about her services at the Hippo dance club, and someone called her supervisor to complain. The supervisor, known as the provincial, also got an angry phone call from Baltimore’s archbishop a few years later after Gramick testified before the city council in support of a proposed LGBT rights bill that the archbishop had opposed.

But these complaints were basically small nuisances until Gramick left teaching and moved to the Washington, D.C., area to partner with a priest named Robert Nugent — whom she enlisted in her work when he wrote a letter of support after seeing a story about her ministry in the newspaper — to launch a full-time ministry for LGBT people.

“My idea was: This is their church and they have a right to the sacraments of their church.”

The duo incorporated their project as New Ways Ministry in the spring of 1978, five months before John Paul II became pope. John Paul II spent the early years of this papacy elaborating a “theology of the body” that placed great emphasis on Catholic doctrine concerning sexuality and contraception. He also installed Joseph Ratzinger in the powerful position of prefect for the Congregation of the Doctrine of the Faith, and the cardinal used the perch to aggressively enforce adherence to Catholic doctrine.

They ran afoul of the Washington archdiocese almost immediately. In 1981, D.C. Archbishop James Hickey — who was made a cardinal in 1988 and was one of the most powerful American church leaders under John Paul II — summoned the duo to his office to read them the riot act about a planned meeting called the First National Symposium on Homosexuality and the Catholic Church. When they did not call off the meeting, Gramick said, Hickey sent a letter to every bishop in the country saying the event was not approved and urged the religious orders that were participating in the event to pull out.

The meeting was held as planned with more than 200 participants, but Hickey, who died in 2004, had only just begun to fight the ministry. He didn’t have the power to shut them down directly, but Gramick said he petitioned the head of both her order and Nugent’s order to force them out of the ministry. He appealed to Ratzinger’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith and another powerful Vatican body overseeing religious orders to bring more pressure.

In 1984, the Vatican ordered Gramick and Nugent to separate themselves “totally and completely from the New Ways Ministry” and not to "engage in any apostolate or participate in any program or write on any subject concerning homosexuality unless [he/she] makes clear that homosexual acts are intrinsically and objectively wrong."

The two were just one of many American religious whose overtures to LGBT Catholics got them in hot water with Ratzinger. In 1983, for example, Ratzinger ordered Washington’s Archbishop Hickey to investigate Seattle Archbishop Raymond Hunthausen following a mass in his cathedral organized by the LGBT Catholic organization Dignity. Hunthausen, who lived to be the last surviving American bishop who participated in the entirety of Vatican II, was ultimately ordered to hand over key powers to Father Donald Wuerl, who is now the cardinal of Washington, D.C. By 1986, dissenting voices had become so loud that Ratzinger felt the need to publish a document titled “On the Pastoral Care of Homosexual Persons” that reiterated that the church considers homosexual acts “an intrinsic moral evil.”

Gramick and Nugent resigned as directors of New Ways Ministry and relocated to the Brooklyn Archdiocese, but after a year they returned to the group with the title of “co-founders” and continued participating in workshops for LGBT Catholics, including some for LGBT clergy and members of religious orders. In 1988, the Vatican created a panel – led by the bishop of Green Bay, Adam Maida – with the mandate to get them to affirm Catholic doctrine on homosexuality.

The panel concluded its work in 1994, faulting Gramick and Nugent for “merely presenting the Church’s teaching [on homosexual acts but offering] no evidence of personal advocacy for it.” The panel was also critical of a book they published in 1992, including a passage that took issue with language in Ratzinger’s “On the Pastoral Care of Homosexual Persons” that said “neither the Church nor society at large should be surprised … [that] irrational and violent reactions increase” toward LGBT people “when homosexual activity is consequently condoned, or when civil legislation is introduced to protect behavior to which no one has any conceivable right.”

Around the time Gramick encountered Ratzinger on the plane to Munich, his office had given the duo a final chance to “to express their interior assent to the teaching of the Catholic Church on homosexuality.” Neither complied to his satisfaction — Gramick said she told the Vatican she would “not reveal [her] personal beliefs because they are [her] personal beliefs.”

When the order came from Ratzinger for them to stop their work, Nugent left the ministry and Gramick temporarily suspended her work. But in 2001 Gramick transferred to another order, the Sisters of Loretto, a move that she believed would circumvent the Vatican’s gag order because of technicalities of canon law. Over the next eight years, Gramick said the Sisters of Loretto leader received nine letters threatening to expel her from the order, but her supervisors covered for her and it was never carried out. (Sisters of Loretto President Pearl McGivney did not respond to interview requests from BuzzFeed News.)

In 2009, the man Ratzinger named to take his place at the helm of the Vatican’s office on doctrine essentially placed the umbrella organization for all nuns in the U.S. — the Leadership Conference of Women Religious (LCWR) — into receivership because of concerns about several issues. New Ways Ministry was singled out as one of the reasons for the takeover.

Everything changed in 2013, when Benedict stunned the church by becoming the first pontiff in centuries to abdicate the post. It wasn’t immediately clear that Francis would chart a dramatically new course from Benedict. And on doctrine, he hasn’t; his pronouncements on church teaching about homosexuality are as hardline as his predecessors.

But Pope Francis’s conciliatory rhetoric toward LGBT people — and small gestures like including the group of New Ways pilgrims at his public audience in February — appears to have been followed by quieter steps creating new space for progressives within the church like Gramick. Her order stopped receiving threatening letters from Rome, and earlier this year the Vatican brought an end to the receivership of LCWR two years earlier than planned.

“Francis doesn’t want conflict at all,” Gramick said. “He doesn’t want to snuff out disagreement or dissent.”

There are many conservatives who disagree with Gramick’s assessment, of course. The most notable dispute at the moment comes from Archbishop Charles Chaput of Gramick’s native Philadelphia, which will host Pope Francis this weekend when he visits the Vatican-organized World Meeting of Families in the city. Earlier this month, Chaput rolled out a contract for parents of Catholic school children to sign affirming their “fidelity to Catholic teaching and identity,” a step that was widely interpreted as part of a campaign to exclude LGBT people from schools in the archdiocese after the ouster earlier this summer of a married lesbian teacher from a school in the Philly suburbs. (Chaput’s spokesperson denies this.)

And the archbishop’s office stepped in to pressure Philadelphia church St. John the Evangelist to withdraw an invitation to a coalition of LGBT Catholic groups to use its space to hold workshops during the World Congress of Families meeting. The church’s Father John Daya did not respond to messages from BuzzFeed News, but Gramick said he told her that he had received a call from a top official in Chaput’s office who “laid him out in lavender” for agreeing to host the meeting.

Archdiocese communications director Kenneth Gavin did not dispute that the call was made, though he said the decision was ultimately left up to the priest.

“In this case, the Archdiocese was asked to evaluate the program and provide guidance, which it did. The end decision was made locally by the parish,” Gavin wrote. “Focusing on this particular matter as LGBT related only would be short-sighted. It’s not about the individuals; it’s about the content of the programming and a consistent ethic regarding the meaning and purpose of human sexuality in the Catholic tradition.”

Chaput, Gramick said, mistakenly puts “doctrine ahead of ahead of people.” And changing that formula is what Gramick believes Francis’s vision is ultimately about, which opens space for LGBT people in the church. Francis may not move to change doctrine about homosexuality, but Gramick believes rules about sexual behavior become less important in a church that is primarily devoted to pastoral care.

“Doctrine doesn't inform ministry,” she said “I think the opposite: Ministry informs the doctrine. In fact, I'm more in line with Pope Francis: I don't think we need to worry or think about or be concerned about doctrine.”

For her, there are just two rules that matter: “We believe in Christ, we believe in the gospel of justice — they're the basic doctrines.”