I recently called the Little Rock Police Department to ask about obtaining the incident report from the night my ex-boyfriend stabbed a man with a knife. “I wasn’t involved; I’m just a writer in New York,” I told the woman who answered the phone, as if I needed to clarify my relationship to Jason’s crime: far away, removed. As if to reassure myself that I was no longer the girl by his side, sharing the consequences of his transgressions.

The stabbing happened in the Little Rock neighborhood of River Mountain on July 10, 2011. Jason was arrested and released on bail. Eleven days later, on July 21, he died in a motorcycle accident while on his way to Walmart in rush-hour traffic. I had just seen him — had just slept with him — for the last time in June.

I thought that if I could get a copy of the police report, I would be able to put that summer back together. I thought I’d be able to draw a clear, straight line between our visit, his crime, and the accident, and then the story of our lives together would finally make sense.

I put the check for $10 in the mail and I waited.

Jason and I met in 2007, at an audition for a tragedy. I was 22 and wanted the role of Medea. He was 18 and didn’t know what the play was about. We were paired as scene partners, and although I remember hardly anything of our actual audition in front of the director, I remember the rest of the night in acute detail: what his mouth looked like blowing Marlboro smoke in the cold when we stood outside the theater, the texture of his suede coat, the snowball fight we had in the parking lot, my wet socks when I removed my boots at his apartment, drinking a pitcher of Kool-Aid he made, and making out on the couch while the Oscars played on the TV and we pretended to watch. The Departed won that year. I drove myself home in the middle of the night, and in the morning there was a voicemail from Jason: “Leigh, I don’t actually hate spending time with you. We should go out sometime. OK, bye.”

Neither of us got cast in Medea, but it didn’t matter — we kept seeing each other. I was anxious, bookish, living back at home with my parents in the Chicago suburbs for the third time, after my life in New York had collapsed and my sublet in Chicago had run out. Jason was the magician, the vision of what my dull, directionless life could become. He was tall, an All-State athlete, with golden skin and pale green eyes. He’d grown up in the South and said “pin” for “pen” and called me "darlin," without the "g."

Even in retrospect, I don’t think I can overemphasize Jason’s charisma; he literally turned heads when we went out together. Strangers would stop us on the street to ask what movie they recognized him from. And he had his own one-bedroom apartment near the community college he attended, which meant I went from early evenings with Mom and Dad in front of the TV to late nights driving around the suburbs with Jason, getting drunk and high, talking in his bed until dawn, feeling like my real life had finally started.

As much as I felt Jason was saving me, I also wanted to save him: He was troubled, neglected, and volatile. A child of divorce, he’d grown up getting shuffled around the South for his stepdad’s career and spending summers with his dad in Illinois. Jason was a smart kid with emotional problems, and none of the adults in his life could deal. His parents and stepparents sent him away to anger management programs and wilderness camps for troubled youths, but from Jason’s perspective, he came out harder, not softer; he bragged to me about all the psychotherapists he’d made cry. I found a pharmacopeia of antidepressants and antipsychotics in his medicine cabinet; he claimed he wasn’t taking any of them because he hated the side effects. And in any case, his tragic childhood, his mood swings — these were part of his allure.

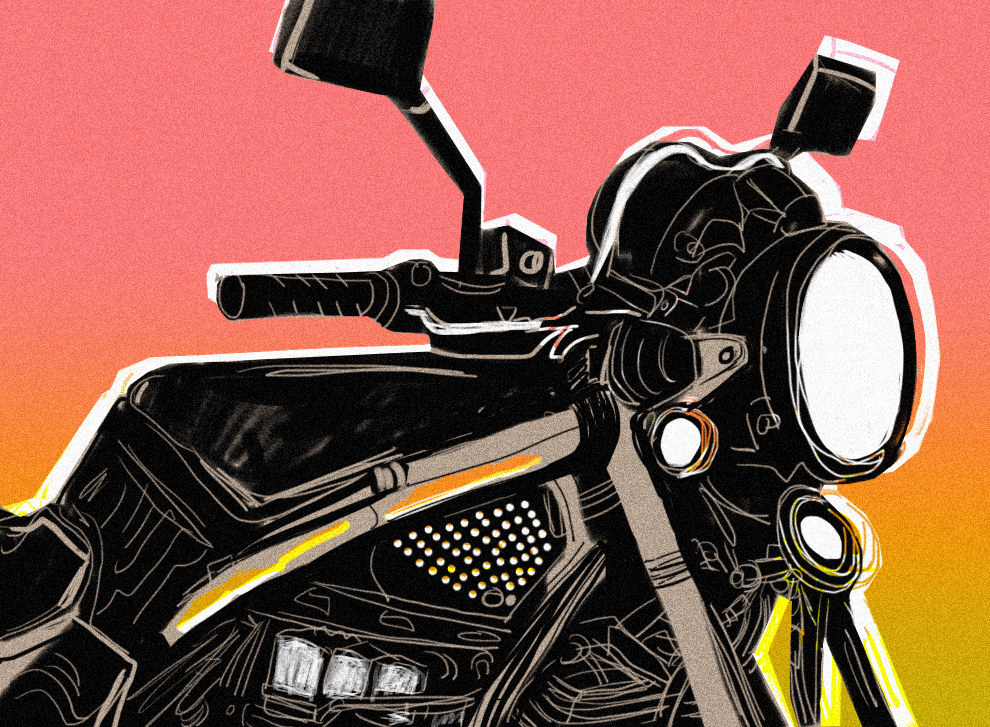

I was with him the day he got the motorcycle — a 1988 Honda Nighthawk, 1988 for the year he was born. Winter had turned to spring, I was now living in his apartment, and I used to sit on the grassy lip of the parking lot and read a book while he took his motorcycle apart and put it back together again to see how it worked. I realized I was doing the same thing with the books I read, and one day told him I wanted to write a novel.

“What if we moved to New Mexico,” he said, “and I could work while you wrote your book?”

“Are you being serious?”

“Yeah, why not?”

“Jason,” I said, “that’s the most romantic thing anyone has ever said to me.”

We were in love. We both wanted to run away. Using all my savings, we moved ourselves and all we owned from Illinois to Albuquerque, sight unseen, in August 2007. We had been together for seven months. My parents were worried, my friends were suspicious, but I was willing to sacrifice their love and attention for the thrill of this great adventure, for the privilege of standing in the shadow of his intense light.

There are parts of this story I wish I didn’t have to remember or tell: how cruel he could be, how manipulative. How, when we fought and I cried, he told me he’d been locked up with people crazier than I was, how he used to unhook my bra through my dress to humiliate me in front of co-workers, how he slapped my 14-year-old sister in the face and I made her promise not to tell. How he insulted all my friends until there were none left who would see us together. How he threw me against our refrigerator and didn’t believe how bad he’d hurt me until I showed him the bruises. My friend Julia calls these “classic” stories of abuse, but for that to ring true I’d have to identify as a victim, and I can’t. Maybe that’s because when Jason was alive, he used to tell me that I always cast myself as the victim in my stories, and the only way to prove him wrong was to stop admitting that he was hurting me. Or maybe I can’t call these stories of abuse because in retrospect, I should have cut him out of my life and instead I yearned for him to stay in it. He isn’t even alive anymore, and here I am — still under his spell. Every time I think I’m finally done telling this story, he grabs hold of my hand and rewrites the ending.

We lived in Albuquerque for six months. I waited tables at a diner and wrote most of the novel that would eventually be published years later, after his death. Jason couldn’t hold down a job. He broke every promise he made to me and, in a twist everyone but me saw coming, our relationship fell apart. I went on antidepressants and anti-anxiety medication to temper the “crazy” Jason saw in me and lost 15 pounds. My hands shook ceaselessly when I poured the piñon coffee at work.

But I told everyone I loved living in New Mexico, because that was the story I could bear holding onto. I loved the glow of the Sandia Mountains, I loved the turquoise- and terra cotta-colored highway, I loved seeing a blanket of stars every night. Even as I literally shrank into a weaker, sadder version of myself, I could never say, “My boyfriend did this to me.” I could only say, “My boyfriend brought me to this beautiful place.”

At the end of our six-month lease, which happened to fall on Valentine’s Day, we packed another truck and drove it north and east across the Ozarks, back to Illinois. Jason moved in with his dad (who had paid for our move; all my money was gone), and I moved back in with my parents for the fourth time. During the particularly wretched weeks that followed, I worked as a temp answering phones at a sump pump company, and tried, pathetically and unsuccessfully, to convince Jason we should get back together. Then my friend Julia called and said she had a lead on a job for me, assisting her boss in the art department at The New Yorker. I burst into tears. “I can’t move to New York right now,” I said. “I’m too depressed.”

I called Jason. “Are you crazy?" he said. "You have to take it.”

Once I was settled hundreds of miles away in my new life, I turned my New Mexico story from one of failure into one of adventure, which I was proud to tell. It went like this: I was just a girl living at home with her parents in the suburbs but then I escaped! I moved to a place I’d never seen and tried things I’d never tried! Aren’t I so unique and unconventional! In this way, I turned my heartbreaking life with Jason into a different kind of love story, one about falling in love with a place, in which I had agency.

What most surprised me, when I finally got the incident report from Little Rock, was that I found myself doing this kind of storytelling again, blurring the facts of what exactly happened so that it could become the story I wanted it to be, one about Jason’s unhinged last days, instead of a story about a crime with a victim and an assailant.

According to the incident report, this is what happened: At 5:40 a.m., a convenience store clerk called the police, after a girl (a "female juvenile”) entered the store and told him that her father had been stabbed. When the police officer arrived at the scene, Jason was sitting on the curb and told the officer, “I was getting on my motorcycle when a white male approached me and asked me for money. I told him I did not have any and he walked toward his car. I went to a nearby vehicle to bum a cigarette. The white male said, ‘What did you say about me’ and came at me. We fought and I pulled my knife to defend myself. He went back to his vehicle and ran over me and my motorcycle and left the area.”

There was a large amount of blood on the concrete, but Jason wasn’t injured. The officer asked Jason who got cut. Jason said he didn’t know. The officer repeated his question multiple times. Finally Jason said, “Someone might have gotten cut,” and pulled the knife from his pocket. It was covered in dried blood.

The first few times I read this, I thought Jason sounded like he was out of his mind. And if he sounded out of his mind, it meant either the report was badly written and I could criticize and dismiss it, or it meant that he was actually having some kind of psychotic break and I could forgive him because he didn’t know what he was saying or doing. Either way I was on his side. Then again, under the category of demeanor, there’s a check mark next to “Calm.” Jason knew how to talk to police, so maybe he wasn’t out of his mind; maybe this was just sophisticated manipulation and I was falling for it yet again.

I had to read it many times before I realized that the girl, the “juvenile,” did what I’d warned my little sister against years before: She told someone what Jason actually had done. And the fact that my first instinct was to protect him against this young girl’s story gave me vertigo. I thought I’d gained perspective with age, and matured into a woman with a sharp sense of right and wrong, but when it came to Jason, my brain was still calibrated to his specifications, so that he would come out the victim in any scenario. That’s why I wasn’t allowed to come off as the victim in any stories about us: I would be taking away the part from him.

I had to squint so hard to imagine him in any other role.

Suspect is light complexioned, with medium, straight, brown hair. The color of the suspect’s eyes is unknown. The suspect is Clean Shaven. Exact Age: 23. Weight: 190. Is the suspect MENTALLY AFFLICTED? Unknown.

Jason had flown from Little Rock to visit me in Brooklyn in June, six weeks before he died. We’d arranged the visit during a seven-hour phone call on Easter, when I was on a vacation by myself in New Mexico, the place I still loved more than any other, after recently getting dumped. I was lonely and nostalgic and Jason fed me good memories and promises of what the future might be. “We aren’t getting back together,” I promised my friends. “I just want to have fun, see what happens. He sounds like he’s in a good place!”

That week in June, we stayed up late. We drank bottles of cheap wine and smoked pot he scored from a guy who worked at the nearest Duane Reade. We had loud sex. He was remorseful, grandiose. “I’m going to be so good to you, it makes up for all the horrible things I’ve ever done to you,” he promised. He couldn’t sleep. He asked for my bottle of Ativan and he crushed and snorted so many pills that when I wanted to bring them to his funeral, I saw they were gone. He had drink after drink after drink and at dawn he was up again, jumping on the bed, demanding my attention. He suggested we go camping together in the Ozarks, or move back to the desert, get a yurt and “live off the land,” but these dreams now sounded like nightmares. By day three I was exhausted and he was irritable. We got into a fight at Coney Island, we got into a fight outside the Met in the rain. He went to a bar while I was asleep and went home with the bartender. I couldn’t wait for him to leave, and my last memory of him alive, of smoothing his cornflower-blue T-shirt across his shoulders and kissing him good-bye on the mouth, is colored by sadness but also relief. It was finally over. I never answered another call or text from him. The last time his number showed up on my phone it wasn’t him; it was his brother calling to tell me Jason was dead.

Months after his funeral, it dawned on me that he must have been manic that summer, and this realization gave me some relief from my grief: He was sick, a victim of mental illness. It all made sense! Poor Jason, he died so young and maybe if he’d gotten better treatment, maybe if he’d had to stay in the jail, maybe the accident would not have happened. And then what? My mind goes blank.

I’ve struggled for so long to come up with an explanation for why our lives seemed so inseparably intertwined, for why I went back to him so many times when his behavior should have kept me away. Was it his charisma? My insecurity, naïveté? Our youth? Was I seduced by the idea that there was this one person for me, whom, for better or worse, I would never escape?

I don’t think I’ll ever know.

I can re-read the police report, all my diary entries, our emails, the poems I wrote him, every document I have of our lives together, but the stories I find there will always conflict, like dissonant piano chords. I can’t bring them to resolve, no matter how many times I keep banging them out. I know that I love Jason, and I miss him — present tense. I also know that when I first heard about the stabbing, the thought flashed across my mind that I could have been the victim. Do I contradict myself? Now that Jason’s gone, I finally have control of our story, and I’m leaving in the contradictions.

After his death, my mom planted a rosebush in Jason’s honor, in the backyard garden that he helped till for my parents when we first started dating.

“I wanted to choose one that made sense for Jason,” she told me. The one she chose is called Knock Out.

Leigh Stein is the author of the newly released memoir Land of Enchantment, and executive director of the nonprofit organization Out of the Binders.