BALTIMORE — The first trial of a Baltimore police officer charged in connection with the death of Freddie Gray, a young black man who died in April after suffering injuries in police custody, ended in a mistrial Wednesday after jurors were unable to reach a verdict on any of the charges after three days of deliberation.

"You believe you’ve reached a point where you believe you will not come to a decision on any of the charges," said Judge Barry Williams, addressing the weary-looking group of jurors. “You clearly have been diligent. You are a hung jury."

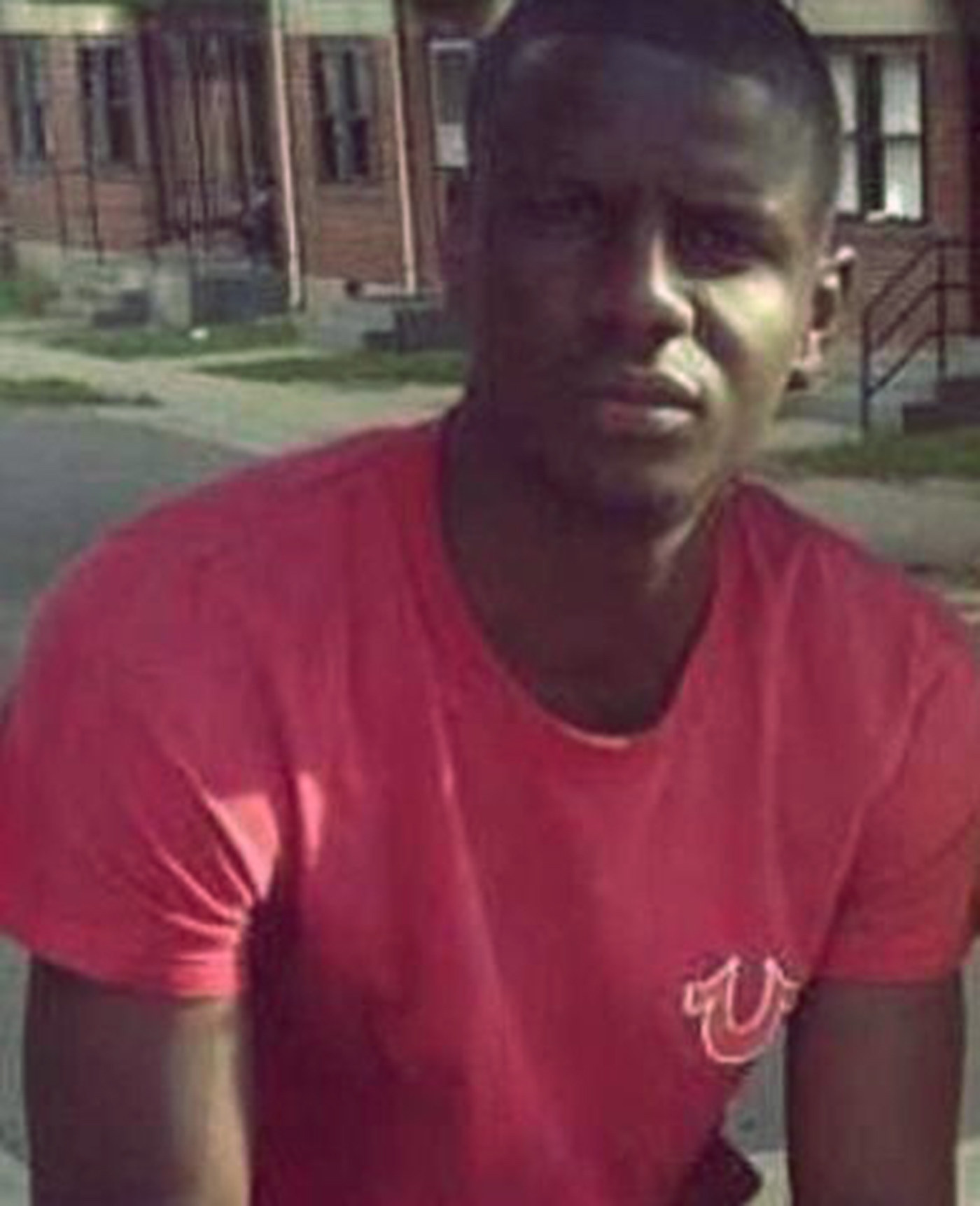

Gray, 25, died in April from a severe spinal injury while in the back of a police van, setting off protests and ultimately rioting in West Baltimore. His death also turned him into a martyr for a national movement concerned with deadly police violence against black people across the country, including Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, and Sandra Bland.

U.S. Rep Elijah Cummings said in a statement that he was informed that the "State’s Attorney’s Office intends to retry Officer Porter." Baltimore State's Attorney, Marilyn Mosby, said that her office was unable to comment on the outcome because of a gag order in place.

A court hearing Thursday to reschedule Porter's future trial was canceled with no further explanation — and the other five officers implicated in Gray's death are scheduled to be tried in 2016.

"This is a temporary bump on the road to justice,” said Billy Murphy, the lawyer for Gray's family. “Each officer has his own trial."

“The mistrial doesn't mean it will be tough to get a verdict in Baltimore," Murphy said.

After the jury announcement a small group of protesters gathered outside the white marble courthouse that occupies a full city block of downtown Baltimore, nudging up against a line of sheriff's deputies standing guard. Two protesters were reportedly arrested.

They just arrested @kwamerose FOR NOTHING. Just grabbed him. This is not a joke. #ThisIsWhyUprising #Baltimore

Another arrest

One of the protesters taken into custody, identified by some on social media as Kwame Rose, was also arrested during the pre-trial hearing for the six officers in September. Rose, a hip hop artist and social activist, had been arrested after he was injured when a car hit him during the protests outside the Baltimore Circuit court.

"If some chose to protest, they must peacefully demonstrate," Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake said. "We are prepared to respond. we will protect our residents, we will protect our neighborhoods...[and] the safety of our first responders."

"Our reaction needs to be one of respect," she said. "We will not and can not be defined by the unrest of last spring."

"We respect the right to protest... our police department respects them," Police Commissioner Kevin Davis said. "Folks who choose to commit crimes... are no longer protesters."

Gene Ryan, the president of FOP3, Baltimore's police union, said, "Officer Porter is no closer to a resolution than he was at that time. Our legal system, however, allows for outcomes of this nature, and we must respect the decision of the jury, despite the fact that it is obviously frustrating to everyone involved."

Porter, 26, faced charges of involuntary manslaughter, second-degree assault, misconduct in office, and reckless endangerment in connection with Gray’s death, which occurred April 19 after he suffered spinal injuries in police custody.

A native of West Baltimore, Porter was one of six officers from the agency's Western District involved in the arrest and death of Gray. Porter had patrolled the streets of his old neighborhood for the past three years, painting himself as a well-intentioned recruit hoping to restore trust in law enforcement.

Porter said he'd even come to know Gray — a drug dealer with a lengthy arrest record — while working his beat.

“Freddie Gray and I, we weren’t friends, but we had a mutual respect," Porter testified last week. "He knew I had a job to do."

Prosecutors accused Porter of failing to get prompt medical attention for Gray, and not restraining him in a seatbelt in the back of a police van while being transported to the station.

Prosecutor Michael Schatzow said during the trial that Porter showed "callous indifference for life," when he did not seek immediate medical attention for Gray, and that he should have known from his police training to do so.

"When someone asks for a medic, you get them a medic," Schatzow told jurors. "When someone says they can't breathe, you get them a medic. [Porter] knew that."

Defense lawyers argued that Porter was ill-equipped to determine if Gray actually needed medical help because Gray did not immediately indicate that he was suffering.

On the witness stand, Porter testified that on the morning of April 12 he responded to the scene where a man had been arrested for running away from an officer. He said he could hear yelling in the back of the van. A few stops later, Porter looked in the back of the van and saw Gray with his wrists handcuffed behind his back and feet shackled.

Gray asked for help sitting up, Porter said. With the assistance of two defense attorneys, Porter demonstrated how he lifted Gray off the floor and sat him on a bench in the van.

Porter testified that he did not put Gray into a seatbelt — per Baltimore police department policy — because he had never seen an officer do that before.

He said he did not notice any major injuries to Gray, but told Officer Caesar Goodson — who was driving the van and is also charged in Gray's death — that Gray would need medical attention.

"It's the wagon driver's responsibility to get him … from Point A to Point B," Porter said.

The defense concluded its case with the testimony of Baltimore police Capt. Justin Reynolds, who said Porter went "beyond what he could have done and kept within [department] policy."

Reynolds said that once Porter checked on Gray and told Goodson that Gray needed medical help, he'd exceeded his responsibility in that situation.

"It's absolutely reasonable that an officer expects when they tell a supervisor something," Reynolds said, referring to Sgt. Alicia White, "that the supervisor is going to do something about it."

Porter’s fate was then placed in the hands of the jury, which was comprised of five black women, three black men, three white women, and one white man.

In a city where blacks outnumber whites nearly two to one, the demographic makeup of the jury was one of the most noted-upon developments in the case. Baltimore always figured to be an intriguing testing ground for the challenges in prosecuting police violence against blacks: Most of the case’s notable figures — the judge, the prosecuting attorney, and the defendant — are black. Indeed, Baltimore has the nation’s fifth-highest proportion of black residents at little more than 65%.

Defense attorneys had previously argued there was no way that Porter — also a black man, but a member of a police force long dogged by accusations of racial profiling and brutality — could receive a fair trial in Baltimore.

Porter's attorney, Joe Murtha, made not-so-veiled references to the atmosphere surrounding the case, which has included regular protests around Baltimore, the resignation of the previous police commissioner, and pleas for calm from the mayor and new police commissioner.

“I understand there’s this need to find somebody, to hold somebody accountable for the death of Freddie Gray,” Murtha told jurors Monday. “That is a natural human reaction. But we sit and stand within the walls of a courtroom.”

By Tuesday, only a few hours into deliberation, jurors signaled that there would be no easy, or quick, resolution: they told Williams they were deadlocked. Williams ordered them back into the room to resume deliberations.

But Wednesday, after 16 hours of deliberation, the jury simply could not come to a consensus.

"I do declare a mistral," Williams told the court.

Porter's reaction to the mistrial was muted. On his way out of court, he nodded to his mother as they were quietly escorted out of the courtroom by Baltimore City Sheriff's deputies. Later, reached by phone by the Baltimore Sun, Porter said, "It's not over yet."

Mosby hugged the prosecutors and quickly left the courtroom with her security detail.

Outside the courthouse in the downtown area, a few small, mostly scattered protests persisted for hours after the verdict. Police helicopters whirred overhead, and law enforcement officers stood guard around City Hall and the courthouse, poised to hold off protesters.

But there was little anger in the streets, only pensive resignation, if not relief that Baltimore seemed poised to avoid the unrest of months ago.

"It's obvious (Porter) played a major part in what happened," said Sean Jackson, 30, from East Baltimore. "But I'm not surprised in the decision, just disappointed. I don't think it's fair."