Next week, when world leaders meet at the United Nations, you're going to hear a lot of good news about usually bad things — like global poverty and malaria.

These are some of the favorite topics at the UN, and at the General Assembly next week, there will be a lot of buzz about how much better we've gotten at dealing with them. In 15 years, malaria deaths have dropped by more than 60 percent. The number of people living in "extreme poverty" has been reduced by more than half. (A lot of them live in China, where population is so huge that it skews the global poverty numbers, but still.)

Cutting malaria deaths and reducing global poverty were two of the eight "Millennium Development Goals" — a pie-in-the-sky vision from the General Assembly meeting in 2000 to focus on making 7 key terrible things better in just 15 years. A World Health Organization review of the goals basically says this: We did a good job on some of them, like reducing the number of HIV cases or the number of kids who die before their fifth birthday. Other ones, like making sure women don't die in childbirth, we weren't so great at.

But our time is up: The Millennium Development Goals were a 15-year project, and they expire this month.

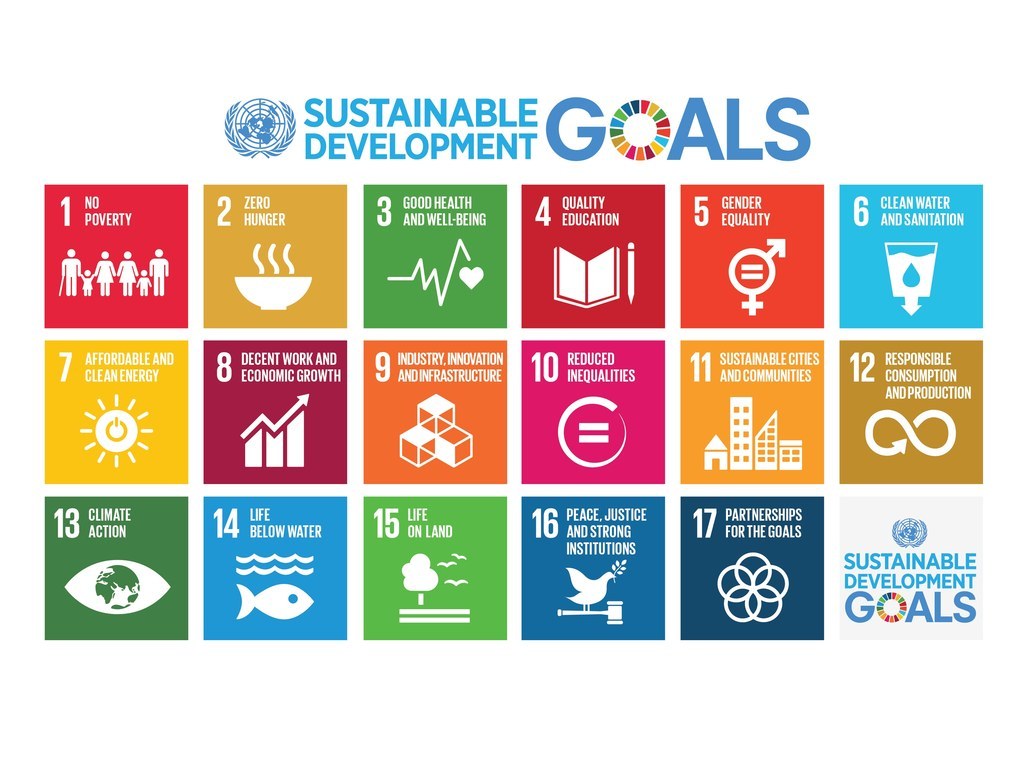

The point is, overall, things are getting better — but the work isn't over yet. Enter an even bigger United Nations idea: the Sustainable Development Goals.

These are 17 goals — with 169 "targets," or sub-goals — designed to make the world safer and more prosperous, to protect the environment, and to promote international cooperation. You know, all the nice things.

The problem is they are expensive.

That doesn't discourage Amina Mohammed, the UN's assistant secretary-general for the SDGs. "The world economy has got trillions and trillions and trillions, and you're only asking for a small part of it," she told BuzzFeed News in an interview at the UN headquarters in New York.

A $2 trillion part, actually.

But she's not wrong about global wealth. A bank of America estimate puts likely global economic output this year at around $70 trillion, and the Boston Consulting Group estimates global private wealth — individual riches — is $164 trillion.

"How do you unlock that?" Mohammed asked. "[There is] money that's available for funding contracts for arms, because that's security. And yet your biggest spending on security should be dealing with inequalities, empowering people's lives...because someone without any hope is a desperate person."

And a new global opinion poll suggests that most of us don't feel all that moved by the moral obligation to help others.

Data provided exclusively to BuzzFeed by polling company Ipsos shows that 53% of people living in 17 countries around the world don't think they have a moral obligation to help countries or people who are worse off than they are. That opinion is even stronger in "emerging" countries like Brazil, Turkey, and Hungary.

But almost everyone agrees that it's important to preserve the earth and promote global equality — two big parts of the new UN agenda.

Ipsos found that 90% of people globally believe it's important to protect the earth. Even in the United States, where climate change can cause real divisions, a whopping 87% thought so. And 81% of people agreed that global equality is important — especially in the United Arab Emirates, where 96% of people support that goal.

And most people want to see more spending on aid.

That's not exactly how the poll put it, but: 48% of people said their countries should spend between 1% and 5% of their national budgets on aid. That's a surprising finding because even the UN's highest expectations are lower than that. More than 40 years ago, the UN asked countries to spend just 0.7% of their budgets on aid. By 2013, only five countries had done so — and none of them were in the survey.