Judging by the "self-help" offered to working women, we are, as a category, case studies in failure. The history of such books and articles dates back to at least 1873, when Harvard professor Edward Clarke warned that a college education would make a woman's brain too heavy and her womb too barren. Centuries later, cover stories like "The Myth of Work-Life Balance," "Why Women Still Can't Have It All," and, of course, "Are You Mom Enough" emphasize women as a social project. Whether it's why we aren't marrying or why we can't have it all, the cycle of trend pieces turned best-selling books remains invested in corrective measures.

To be a woman is a never-ending process toward perfection. The journey is the destination, probably, but the journey is also a mandatory part of the performance married to conventional representations of gender identity. If you would like to be called a woman, there is a set of responsibilities that you must consistently perform, appearances that you must keep up, and most important, a certain amount of effort you must exert that is largely invisible to those watching you.

Feminist theorist Donna Haraway's studies and writings on simians, cyborgs, and women are, in her words, studies on three different kind of monsters within the scientific community and the world at large, pointing to the original meaning of "monster": to demonstrate. Haraway offers an elastic philosophy that can liberate us from the faux affirmations of a feminism designed for business women with book deals. In 1991, Haraway published Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, a collection of her essays about the intersection of biology, the myth or fetish of scientific objectivity, gender, sexuality, race, labor, and feminism.

Haraway understands that self-help is often a catch-all phrase to fix what isn't broken; that the genre allows unquestioned scientific biases and philosophical queries into ideas of labor, gender, sexuality, family, and identity to sneak by, provided the title is catchy enough. Her cyborg manifesto, is almost 30 years old — in fact, just old enough to become new all over again.

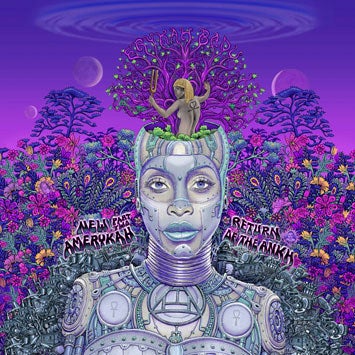

In March, Rachel Kaadzi Ghansah wrote an article on Beyoncé and her fans, the "Beyhive," and compared Beyoncé to Haraway's cyborg, an incredibly perfect analogy: "Is Beyoncé a feminist? Is she a womanist? I don't know. To me she is a cyborg."

"Cyborg writing," Haraway tells us, "is about the power to survive, not on the basis of original innocence, but on the basis of seizing the tools to mark the world that marked them as other. What I appreciate about Beyoncé is that I understand and recognize the tools seized."

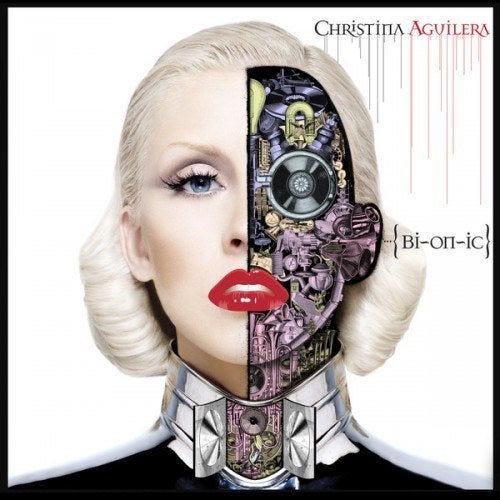

A female body — all bodies, really — is a machine. Every part of the body is part of a central communication system, relaying information and performing the labors necessary to live (inhaling, exhaling), necessary to participate in society (saying please and thank you, chewing with our mouth closed), necessary to stay a productive member of our societies (having a job, paying rent). The only reason we don't consider our labor the labor of a robot, which is a Slavic word literally meaning "to labor," is because we are composed of entirely organic material.

Haraway defines cyborgs as "post-Second World War hybrid entities made of, first, ourselves and other organic creatures in our unchosen 'high-technological' guise as information systems, texts, and ergonomically controlled laboring, desiring, and reproducing systems. The second essential ingredient in cyborgs is machines in their guise."

Haraway's Cyborg Manifesto asks us to wonder why our bodies should be seen as apparatuses that end at our flesh. Why settle for only the physical world as we see it, when it comes to our lived social relations? Haraway was originally writing against being lumped into a category she didn't want to be assigned to, an origin story created by someone thinking too small (too human), simply one of Reagan's special interest groups instead of an identity of her own making. Haraway writes about the failures of second-wave feminism to recognize the varied experiences that come from differences in sexuality, race, class, asking instead to embrace a technological approach: "Feminist cyborg stories have the task of recoding communication and intelligence to subvert command and control."

"The main trouble with cyborgs," Haraway concedes, "is that they are the illegitimate offspring of militarism and patriarchal capitalism, not to mention state socialism. But illegitimate offspring are often exceedingly unfaithful to their origins. Their fathers, after all, are inessential." A cybernetic organism, composed of organic and machine material, can rest easy knowing that they have a purpose on this planet, that their occupation does define them, and that no one will ever imply that they are not cyborg enough, unfit for participating in the rigid confines of preapproved life milestones.

Nobody ever asks if a cyborg can have it all. Nobody ever tells a cyborg to lean in. For a cyborg, identity is a fusion of organic and/or human elements with machinery; a cyborg cannot be one thing, stretched in too many directions, because a cyborg has always been a multiple within itself.

Years of slavish devotion to my own labor and the labor I sell to companies and individuals at a premium rate has already made me into a kind of machine; I am an impatient, unsatisfied person, constantly looking at the easily quantifiable achievements of my labor and forcing myself to do the same, but better and faster, next time.

That's the impulse propping up a significant amount of the print and digital publishing industry — the financial success of Lean In is just one more title in a long list of self-help or motivational literature aimed at making women better at, ostensibly, business, but the female category has both blurred and sharp edges; self-help literature for women is part of the implication that women need help at being better at everything; that if she is to be a better boss, employee, and most importantly team player, she must also be taught to be a better monogamous heterosexual spouse, better mother, better at being conventionally good looking, better, better, better.

Yet cyborg is not some sort of easy third option. We cannot just shed our titles (particularly the ones that mark us as other) as easy as Haraway asks us to. To be white, to be middle class, to work in a creative profession; these are the identities that can never be discarded. They're also the only elements of personhood on display in these contemporary manifestos asking women to work harder and be better. To look at The Atlantic, or Sheryl Sandberg, or any number of fear-mongering try-harder parables creeping closer and closer on our horizons, you'd think these are the only kinds of women who exist.

These books and articles are not offensive, necessarily; I just hate that they ask us to make a woman neutral, to redefine what a woman is capable of and not the category we assign ourselves in this world — to make an assigned gender better at participating in our existing hierarchies, not find and build our own tools to create better roles and better dreams. In the version of the world put forth by these books, "woman" feels like a hopelessly limited category and "work" even more so. It privileges a Western conceptualization of self which Haraway points out doesn't allow for "polyvocal, unassimilable, radical difference made visible in anti-colonial discourse and practice."

I cannot abide by that tone claiming ladies are just in this together: girls nights and other segregated socializing, grouping us by the most tenuous links, like that I was born with a vagina and live as a female-identified person, and that's enough for the publishing industry to feel confident that Sandberg will speak to me. There's a special place in hell for people who sincerely say, "Listen up, ladies," which must be the last thing you hear before you enter the underworld, and, "We're all in this together," the first after passing through the rings of fire.

Haraway, by contrast, writes that "there is nothing about being 'female' that naturally binds women," a welcome reprieve from a false sisterhood. In 1985, decades before Sheryl Sandberg left Google to work for Facebook and asked us to make similar leans in our lives, Haraway warned, "Work is being redefined as both literally female and feminized, whether performed by men or women. To be feminized means to be made extremely vulnerable; able to be disassembled, reassembled, exploited as a reserve labour force… leading an existence that always borders on being obscene, out of place, and reducible to sex." The cyborg that Haraway wants to be is "an imagination of a feminist speaking in tongues to strike fear into the circuits of the super-saves of the new right. It means both building and destroying machines, identities, categories, relationships, space stories." I would rather be that cyborg than ban bossy.

When I consider what a woman is — or what a woman should be, according to the peanut gallery offering helpful suggestions at a reasonable price — I wonder, like Donna Haraway, if the category we call woman is not already some sort of cyborg, a hybrid body made up of organic material and the implanted subconsciousness of those voices telling women how to behave, how to be better. These suggestions seek to make women robotic in their uniformity; voluntary Stepford Wives.

Maybe, instead, we should think of our consciousness as a circuit board that we are in control of. Instead of being something that must be formed, we can hold ourselves as individual units open to being rewired, to adapting to new advances, and not simply mechanisms who are in need of constant repair from some sort of patriarchal tool box.

Our existing infrastructures fail us because they think we're already broken. The internalized lessons of aspirational literature, pharmaceutical aids intended to keep women laboring at appropriate levels, the woman watching herself being watched to keep her a cog in a wheel — the same narratives we'll hear as long as there's money to be made in telling a woman that she's doing it wrong. What I want is the ability to communicate everything I think and feel without ascribing to platitudes or cliches; to work as a means to its own end, work that I do because I love it, because it gives me purpose, because it keeps me as a machine in service for myself and not because I am a well-oiled cog in a larger machine; to live on a timeline that I determine, not one determined by a fear of breaking tradition.

These are not desires that lend themselves to self-help and productivity literature aimed at my category of human. But they are part of the stories told to women about why they are wrong, why they aren't working hard enough to have it all, the most hateful of all platitudes. "Our bodies, ourselves; bodies are maps of power and identity," Haraway writes, "Cyborgs are no exception… Intense pleasure in skill, machine skill, ceases to be a sin, but an aspect of embodiment. The machine is not an it to be animated, worshipped, and dominated. The machine is us, our processes, an aspect of our embodiment."

"The power to determine the language of discourse," Haraway says, "is the power to make it flesh." Our words, our methods of communication, our tools, are battlegrounds — I am looking for a collection of words that I wear as armor; I want our bodies and identities to be things we are building not because they're broken, but because we are constantly defining for ourselves what better means. Having it all, for us, is thinking too small.

Haraway's Cyborg Manifesto is not designed to help, or improve, the lives of all women everywhere; it's her call for readers not to do better, but to think better. We pretend science is only discovery, not subject to the same biases humans bring to every single thing they touch, the same way we do with these classic self-help narratives; we pretend these are just the facts, just the truth of how people succeed, as the best way to find people to emulate and eventually become. If I could just figure out exactly how Sheryl Sandberg got where she is, and break it down into individual easily packaged and purchased components, I can be Sheryl Sandberg, is the thinking that sells books. But being the cyborg feminist Haraway describes means being someone/something completely devoted to the promise of impeccable work at my own standards.

For people who do not want to participate in — or have not been included in — ironclad interpretations of what it means to be a woman, Haraway has given us a tool that also functions as a weapon. Lean in? Lean the fuck out of my way.