WASHINGTON — Earlier this year, the Obama administration Justice Department announced sweeping reductions in the sentences for nonviolent drug offenders, an announcement that was heralded in the press and by advocates, liberal and conservative alike.

But when it comes to people already in prison for those very same drug offenses, the Justice Department is taking a very different stance: Officials have recommended a policy that would keep tens of thousands behind bars under the old guidelines, a decision that has set off a firestorm among advocacy groups on both sides of the aisle.

The sentencing rules for federal drug crimes were established in the 1980s, sending thousands to prison for long sentences with the goal of reducing drug crime — a policy demonstrated to disparately affect minorities, and the subject of intense advocacy in recent years. The Justice Department announced its support earlier this year for new guidelines recommended by the U.S. Sentencing Commission that will lower the sentences for future offenders by an average of 11 months versus sentences handed down today.

Since that decision, however, the department has asked the commission, an independent board that creates sentencing guidelines for federal courts, to make thousands of drug offenders currently serving time exempt from those rule changes. On Friday, the commission will vote on the issue. Sources familiar expect the ruling to come sometime in the mid-afternoon.

In the balance: Whether 50,000 drug offenders serving time will be able to petition a judge to review their sentences according to the new standards.

That number represents around 25% of the total federal prison population — approximately 210,000 convicts — a daunting figure that has made even the advocates for change in the Justice Department blanch.

"The Justice Department is being very pragmatic here," said Doug Berman, a professor at Ohio State law school and a leading expert on the Sentencing Commission and its decisions. Inside the department, there are fears about what allowing 50,000 prisoners to have their sentences reevaluated will mean.

For instance, Georgia U.S. attorney Sally Quillian Yates, who represented the Justice Department at June sentencing commission hearing on retroactivity, argued evaluating years-old specifics in cases could prove challenging. "That...would require a tremendous amount of administrative assessment," she said of one hypothetical involving gun possession. "And in the cost and benefit analysis, and in weighing these factors we don't think that that's an appropriate use of resources."

The Justice Department is urging the commission to adopt guidelines requiring drug cases involving a gun in any way or a more nebulous "obstruction of justice" to be ineligible for review by a judge. Justice Department officials have admitted some offenders worthy of sentence review could fall through the cracks, though they've said that's a necessary evil given the limited resources available. The Justice Department plan would cut the number of prisoners eligible for retroactivity from 50,000 to about 20,000.

Behind that proposal, say observers, is the messy politics of actually dealing with the impacts of the drug war that a growing bipartisan chorus say they want to see ended. The challenge of retroactivity has pit the Obama administration — the most open to changes in law since the drug war began — against many of its allies who say the Justice Department's caution in the face of retroactivity makes them question the administration's commitment to the cause.

Berman said the department's plan reflects the difficult politics of retroactivity. While it's relatively easy to champion a change to sentencing for future drug offenders, reducing the sentences of thousands convicted for drug crimes means reexamining and in some cases unwinding the efforts of federal prosecutors who often measure their effectiveness with the number of people they've put behind bars and the amount of time they've put them there. That's not an easy ask and, as the Justice Department's ongoing efforts to prevent that reexamination from happening in the first place shows, one that administration officials are wary of embracing.

"There are some members of the commission who say, 'let's go for full retroactivity and let the chips fall where they may,'" he said. "There are others who are like, 'You know what? Enough is enough and let's go forward and not backward.'"

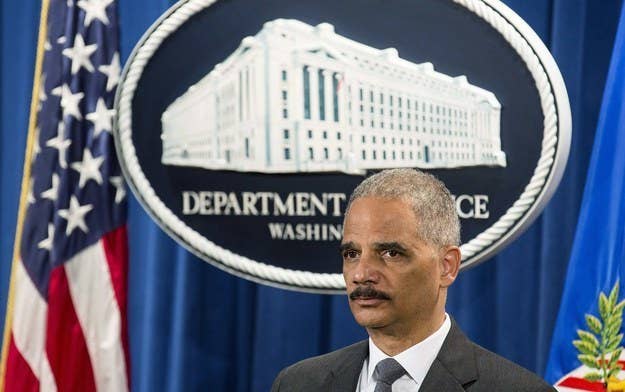

A Justice Department official declined to directly respond to the critics of the department's retroactivity proposal, but pointed to Holder's June testimony before the sentencing commission. Holder said full retroactivity would pose a risk to public safety.

"Not everyone in prison for a drug-related offense would be eligible. Nor would everyone who is eligible be guaranteed a reduced sentence," he said. "But this proposal strikes the best balance between protecting public safety and addressing the overcrowding of our prison system that has been exacerbated by unnecessarily long sentences."

But the department's recommendations have set off a wave of outcry in the very active advocacy community around criminal justice issues — pitting many of the Obama administration's biggest supporters against them.

The NAACP, National Council of La Raza, several prominent LGBT groups, and three progressive senators have all petitioned the sentencing commission to ignore the Justice department, warning that the exceptions desired by the Obama administration will adversely affect minority convicts. NAACP lawyer Kim Keenan said her group's letter full retroactivity is the only way to address "the past unconstitutional and disparate treatment of minorities."

The administration allies say the Justice Department's concerns about resources don't jibe with the Obama administration's promise to make addressing the impacts of the drug war a priority.

"I don't think that money should be the factor that prevents justice from prevailing. So if that's the only argument that there is I don't think that's fair to the communities that are being impacted," said Meghan Maury, a top lawyer at the National Gay and Lesbian Taskforce, which also submitted a letter to the commission calling for full retroactivity. "If the number is one dollar or $1 million, justice shouldn't be run by money."

White House opponents are also angered by the Justice Department request. Leaders in the conservative movement to reduce drug sentences in the hopes of spending less money on the drug war are also petitioning the commission to ignore the administration request and vote for full retroactivity. In its letter to the commission, the American Conservative Union warned that following the Justice Department guidelines would be an "injustice." Republican Sen. Rand Paul, perhaps the right's most vocal supporter of ending the drug war as we know it, joined the letter signed by progressive Democratic Sens. Dick Durbin, Patrick Leahy and Sheldon Whitehouse that doesn't directly call out the Justice proposal, but calls anything less than full retroactivity "would create new inequities in our system."

Families Against Mandatory Minimums, a group that straddles the fence when it comes to the White House, having counted on the two most polarizing billionaires in politics — George Soros and the Koch brothers — for financial support, also opposes the Justice Department proposal. Mary Price, FAMM general counsel, said it's impossible for the Obama administration to reconcile a push for new sentence guidelines while pulling back from retroactivity.

"It is pretty stunning," she said. "Everything that has been coming out of that department, and I'm talking from the Attorney General on down, has been about reducing the amount of people [subject to long drug sentences.]"

Price noted that Holder supports the Smarter Sentencing Act, a stalled bipartisan legislative push to make the crack cocaine vs power cocaine sentence reductions passed in 2010 retroactive. "The (Justice Department) has been ahead of everybody" on sentence reductions for future offenders, she said. The department's retroactivity stance "is a case of 'golly, what are you thinking?"

Not all the critics claim the Justice Department is being too harsh with its proposed retroactivity exemptions. The National Association Of Assistant U.S. Attorneys, a group that has publicly opposed every attempt at drug sentence reduction in Congress and at the executive level, submitted a letter to the commission that warned the Justice Department was on dangerous ground endorsing any retroactivity at all. "Allowing an individual sentenced under a plea agreement to have his sentence reduced retroactively prevents the government from obtaining benefits gained through concessions during bargaining, while allowing defendants to make considerable gains without risk," wrote the association's executive director.

Rarely would the offenders at issue be released right away. FAMM and other groups say the average sentence reduction for existing offenders would be 23 months, meaning prisoners currently behind bars who make their case for retroactivity to a judge would still have to serve out their existing sentences minus two years (plus whatever sentence enhancements prosecutors successfully added to the prison term, none of which would be altered by full retroactivity.) The expected window of current inmates affected by retroactivity spans the next 30 years.

This isn't the first time Price and the other groups have taken on the Justice Department and Holder over full retroactivity. In 2011, Holder personally testified at a sentencing commission hearing examining whether or not to make new crack vs power cocaine sentences retroactive. Holder spoke to the need for retroactivity but said it should be limited "beyond current commission policy." That is, many crack offenders should be exempted from the new guidelines, in Holder's words, to protect public safety. In the end, the commission voted unanimously to grant full retroactivity, ignoring Justice Department recommendations.

No one observing the commission is ready to expect the same result this week. The commission is a political body — members are picked by the president and confirmed by the Senate. Three of the seven commission members must be federal judges and no more than four can be members of the same political party. Commission hearings surrounding retroactivity can be a raucous affair (for a relatively unknown Washington commission of elder jurists, that is) and politics play a part. Most see the commission as leaning to the conservative side of the ideological spectrum, which means they might be open to the Justice Department argument that 50,000 sentence revisions are just too much for the system to handle.

Berman, the professor, says Holder's testimony in 2011 about safety and Yates' testimony in June about resources are cover for larger forces roiling the Justice Department and the larger movement to reexamine the war on drugs: Prosecutors don't like the idea of their sentences being shortened, and politicians don't want to risk the blowback if any of the prisoners whose sentences get shortened commit violent crimes down the road.

How the commission splits the difference could have wide-ranging effects, he said.

"You see this from the law enforcement folks especially: 'We're debating the challenge of giving these folks a kind of extra justice. And these aren't people who deserve that extra justice. Maybe we can concede that they got slammed a little hard before. But you know what? They've got no one to blame but themselves,'" Berman said. On the other side, Berman said, "Those are people's mothers and brothers and sisters and mothers" serving time under rules that have changed.

How the sentencing commission decides Friday could determine which of those two arguments become the basis for retroactivity going forward.

For advocates, the internal battles in the Justice Department and among law enforcement over retroactivity are a distraction from the issue at hand, which they say is simple fairness.

"Sentences should take into account the crime and the role of the offender," said Antonio Ginatta, advocacy director at Human Rights Watch. "If [sentences] are too long going into the future, they're too long looking back at the past."