The British documentary 56 Up, is airing exclusively on U.K. television right now. Part of the acclaimed and popular decades-long Up series, which has revisited the same 14 people every seven years, it’s an important and unique documentary. But there’s no date set for when or if it will air on TV in the U.S.

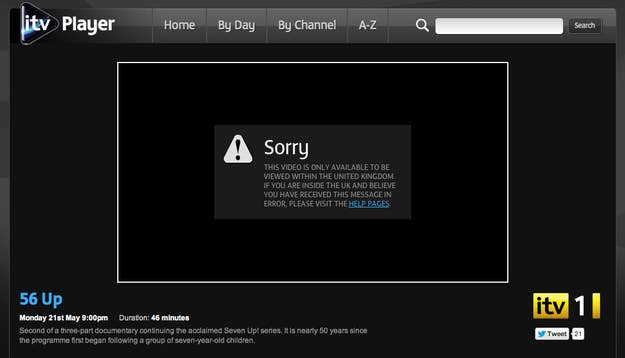

ITV, the U.K. television network and the studio behind 56 Up, is streaming the film on their website. But the moment the page loaded my excitement was crushed when I was met with a pop-up that read: “Sorry. This video is only available to be viewed within the United Kingdom.” So it’s not available online on this side of the Atlantic, either.

Seemingly, the only way to watch it is illegally. Which is ridiculous, as I’ve argued before.

Then I received an email that changed everything. A reader of my piece for The Atlantic, and a diehard fan of the series, told me that there is a way: a VPN (virtual private network), which essentially disguises where your IP address is located, so you could be in one country but it appears that you are located somewhere else — like the U.K. (VPNs typically have received press for their use by dissidents and journalists in authoritarian states like China so they can have unrestricted use of the web.) There are multiple types of VPNs and the details about how they work get pretty technical. But in a nutshell, as Pete Davis, a VPN expert from tech giant Cisco explained to me, “normally the end user’s IP address is located in whatever immediate area he is in, but with a VPN you use a piece of software on your computer to establish a connection with a server at some other location.”

But before I pulled the trigger on using a VPN to watch the series from across the ocean, I had to know: Is it legal? After contacting numerous attorneys who specialize in Internet and intellectual property law, the short(ish) answer is “basically yes, but it’s complicated.”

To be philosophical about it, who or where are you, really, when you’re online? Are you the physical person sitting in your chair? Or is it fair to say that you are who or where your computer or connection says you are? By using a VPN — one in the UK for instance — to access the internet and do your thing, "for all intents and purposes you are watching the show from the U.K.," explained Bret Fausett, a lawyer based in Marina del Rey, California, with extensive ties to ICAAN (the organization that oversees the use of Internet domains). Among the attorneys I spoke with, Fausett was also the most blunt in answering whether this is legal. He flat out says, “It’s not a crime.”

If anyone is going to be held liable for deception by connection to watch TV, it’s probably not the user. “The VPN may be subject to legal action,” Joshua Mooney, a Philadelphia lawyer who handles intellectual property matters in cyberspace, noted. “But holding a consumer — specifically a US consumer — liable is different." To nail a user for infringement, a company would have to meet a very specific checklist.

Interestingly, Mooney believes that the technology involved may play a role in the legality of using the VPN for watching content. Watching streaming content, he said, may have different implications than downloading content. “If the content somehow is being converted from one format to another, it’s possible you technically are copying it [during the conversion process]." Which means you'd be breaking the law. But if you're watching a straight, unconvereted stream at home, then you're probably okay.

The main reason that content gets geo-locked, the lawyers theorized, is over copyright and licensing issues that haven’t been dealt with by the provider. Largely due to old, outdated distribution modes, the world gets divvied up into different territories with different rights holders for each region. Content providers, the lawyers said, fearful of running afoul of rightsholders in one region or another, take the easy route and simply “lock” their content to the limited area they know they’ve secured rights for. “Providers don’t want to be held accountable if they broadcast a U.K. show in the U.S. without getting appropriate licenses first,” Mooney suggested.

Beyond technical and licensing issues, another issue affecting legality is whether or not the content is free. “If a provider is charging for it in the U.S., but it’s free in U.K.," and you’re watching it for free in the U.S. using a VPN, then you could run into some issues, Fausett said. He noted, though, that in gray areas of the law like this there’s always a counterargument to be made. “If the content is not available in the US,” he mused, “and is available in the U.K. for free," such as the case with 56 Up, "then I think that’s a hard case to prove wrongdoing, because you didn’t steal anything.”

Another hypothetical: You’re in France, and you’re using a VPN to watch a Netlfix movie streamed from the U.S. that's also available for purchase via French websites. In this scenario, “It’s not clear whether this is legal." Fauset said. "It could be legal because you are accessing the content from the US." The reality is, the law in this area is so open to interpretation that no one really knows for sure.

I gave Fauset a last scenario: What if you’re in the US and you use a VPN to purchase content that’s only being sold in U.K.? “As long as you are buying it, then there’s no problem,” he explained. “It’s no different than having a friend in the U.K. going to a store and buying it for you.”

Erik Syverson, a Los Angeles-based attorney who has “made Internet law the cornerstone” of his practice, puts the onus on the content provider. “It’s a language problem,” he said. “If I’m ITV, and if I want to restrict this technology, then I need to come up with specific language on my site saying, ‘Don’t use a VPN.’” He adds, “The interesting question isn’t whether something is illegal or not. Legality has little to no influence on human, and particularly entrepreneurial, behavior. You would be paralyzed; there would be no innovation if everything done was legal.” After all, he noted, “YouTube was a business founded upon knowing it had copyright infringements.”

I’m not blindly in the “information wants to be free” camp. ITV should charge for this content. Films cost money to produce, and I’d happily give money to support the series so it can continue. What I am arguing, ultimately, is instead of clinging to outdated legal constructs, providers would do well to make their content available immediately everywhere and charge for it. As Syverson said, “I’m not a studio head, but the old methodology of rolling out content region by region doesn’t make sense. These types of restrictions are a bad idea because people will always find a way to get it.”

If you’re curious to check out “56 Up” and don’t want to wait, you can hop a plane across the Atlantic tomorrow. Or you can use My Expat Network, the VPN used by the fan who emailed me. (At 5 £ a month, it’s a hell of a lot cheaper than a seat on a Virgin 747.) Their servers are located in the U.K., and, if you use them, by extension, so are you. There are a bunch of other good VPNs, too, like StrongVPN.

P.S. While attorneys were used as sources for this article, they are not your attorneys, and this piece does not constitute legal advice.

David Zweig is writer, lecturer, musician. He writes mostly about the intersection of technology, media, & psychology. You should follow him on Twitter, or Facebook, if that's your jam.