Buta Singh hadn’t eaten in days, and his body felt like it was vibrating with hunger as he sat up on his bunk bed and watched the prison guards storm in.

The guards rounded up two dozen or so young men, all of them, like Singh, immigrants from the Indian state of Punjab. There was someone there to see them. Unbeknownst to Singh, the visitor was a representative from the Indian government. As he shuffled after the guards in his baggy navy-blue uniform — the uniform he’d been wearing for 10 months, issued by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement — Singh wondered whether the visitor was some higher-up from ICE, there to make a deal.

Like Singh, the Punjabis were followers of Sikhism, a religion that emerged some 500 years ago in the region now bisected by the border between India and Pakistan. Sikhs are usually recognizable by their beards and long, turbaned hair. But the ones in this group had shorn their heads and faces to better go unnoticed on their journeys: by air from India to the New World, by land through Central America, and finally to the line dividing Mexico from the United States. Most were asylum-seekers and had passed interviews that determined they could stay in the country as their claims moved forward, and many had close family members living legally in the U.S. — yet the government refused to release them.

So, on April 8, 2014, the Punjabis at Texas's El Paso Processing Center went on a hunger strike. It was about a week later when Singh, feeling shaky on his feet, walked into the meeting room where the visitor was waiting. He was startled to see a short, rotund man in a turban with his beard tied underneath his chin: a fellow Sikh from the Indian consulate in Houston. He was there to offer to send the detainees home.

Should they decide otherwise, the diplomat said, they were wrong to think their hunger strike would sway the American authorities. Singh’s surprise turned to anger. In India, he had been active in a fringe political party that advocates the creation of Khalistan, an autonomous Sikh state. The police in Punjab have a history of persecuting separatists, and Singh sought refuge elsewhere, he says, after they tortured him one too many times.

Now he was in America seeking asylum from the Indian state, and here, facilitated by the U.S. government, was an emissary of that very state. (The Indian Embassy did not respond to requests for comment.)

“None of you are doctors,” the diplomat said. “None of you are engineers. Why would America want you?”

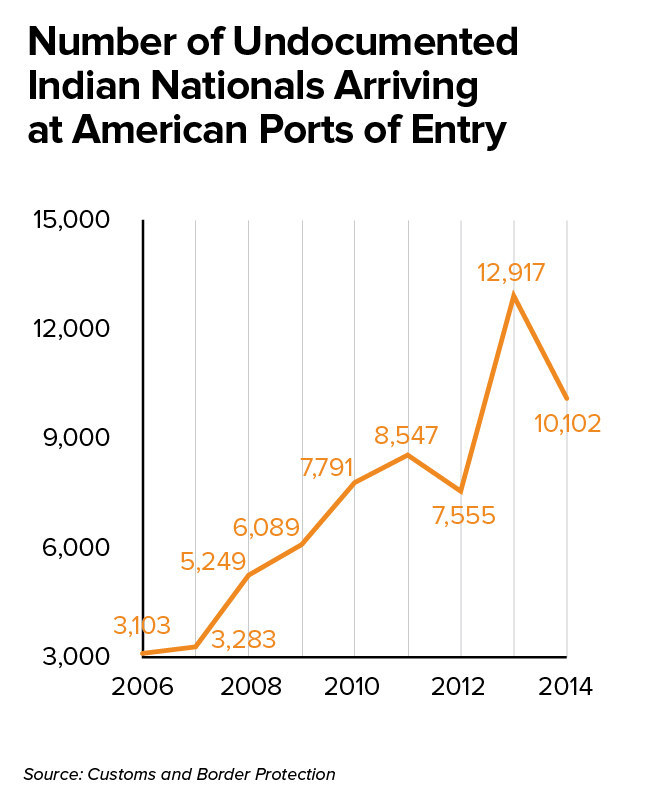

The number of Indian nationals caught trying to cross the southern border into the U.S. exploded suddenly in 2010, growing sixfold to 1,200 from just over 200 the year prior.

Although the number has oscillated since then, it has remained near an all-time high. And that includes only those caught trying to cross undetected, leaving out Buta Singh and others like him — thousands, mostly young men, who walk up to a border crossing, turn themselves in, and plead asylum. The total number of Indian nationals who tried to enter the U.S. without papers, including through airports and other points of entry, also spiked in the last five years, peaking at close to 13,000 in 2013, more than double the number in 2009.

Much of this influx, according to dozens of interviews with immigrants, experts, and current and former immigration officials, comes from young Indian men at the border, ferried there by transnational smuggling networks. Although border authorities do not track the religious or regional origins of migrants, government officials and other observers say that large numbers of the new arrivals are Sikhs from Punjab, a region in northwestern India beset by economic collapse and environmental degradation, a major drug epidemic, and decades of what human rights groups describe as political violence carried out with impunity.

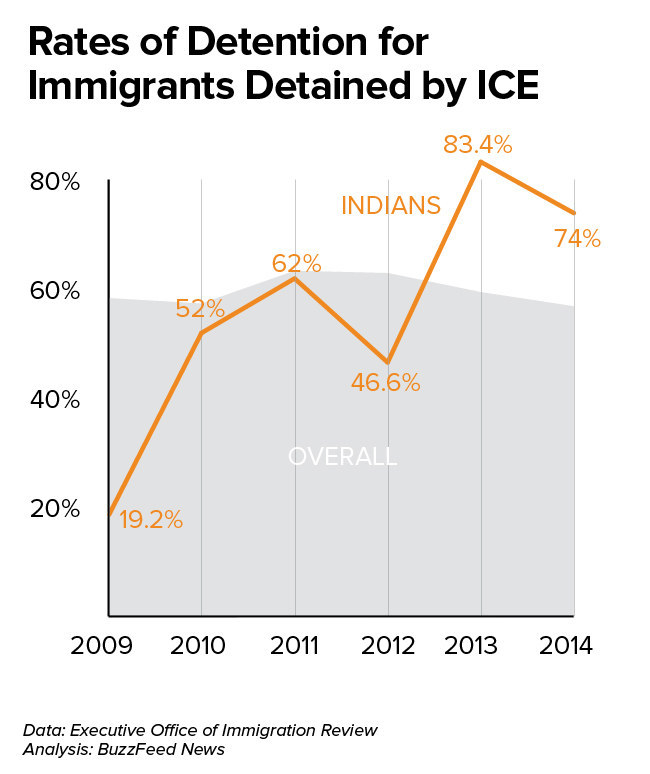

The American immigration enforcement apparatus has responded harshly to these new arrivals. Before the spike, only about a quarter of Indian nationals were detained at the beginning of their deportation hearings. But, according to federal data analyzed for the first time by BuzzFeed News, that percentage shot up dramatically around 2010, coinciding with the rise in Indian nationals at the border.

In 2013, the year Buta Singh arrived in Texas, 83% of Indians facing deportation were imprisoned — a far larger percentage than for immigrants from any other country, including Mexico, which had the highest overall rate of detention between 2003 and 2014. (BuzzFeed News obtained the data through a Freedom of Information Act request from the Executive Office for Immigration Review, or EOIR, the branch of the Justice Department that operates the country’s immigration courts.)

ICE refused to comment on these findings, citing the fact that the data comes from a different federal agency. “ICE is focused on smart and effective immigration enforcement that prioritizes its available resources on those who pose the biggest threat to national security, border security and public safety,” Sarah Rodriguez, an agency spokeswoman, told BuzzFeed News.

Two former ICE employees, who spoke to BuzzFeed News on condition of anonymity, said the agency has an unofficial policy of cracking down on Indian immigrants, especially in states along the border. This policy is connected to the widespread belief among immigration authorities that the smuggling networks bringing Sikhs to the border are training them to file false asylum claims and disappear into the interior of the country. The government also fears these networks could be used by terrorists. As one former official described the approach: “Keep them out. If you catch them, detain them.”

Buta Singh’s 33 years, from his childhood and young adulthood in Punjab, to his voyage to America and his incarceration in Texas, tell the story of this mass migration. When he first arrived in El Paso in June 2013, trading the filthy clothes he’d worn on his journey for ICE’s navy-blue uniform, Singh didn’t expect to be imprisoned for long. But as the months dragged on, it seemed to him and the other young Sikhs in the South Texas jail that the government was singling them out.

Yet the Sikhs keep arriving. On April 10, 2015, a company that sells turbans online got an email from an ICE prison near the border: “Florence immigration Federal Detention Center in Florence, Arizona again. We are experiencing another surge in our Indian Sikh population here and I’m wondering if you could send me some fresh turbans to share with the men. Right now we have 45 Sikhs and each week the number increases.”

In 1984, two years after Buta Singh was born, the Indian army stormed into the city of Amritsar and laid siege to the Golden Temple, the holiest Sikh shrine, with tanks and heavy artillery. They were after a man named Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, the leader of an armed separatist insurgency loosely known as the Khalistan movement. Bhindranwale had turned the temple complex into barracks fortified with snipers, machine guns, and grenades.

The operation, code-named “Blue Star,” killed Bhindranwale and reduced much of the temple complex to rubble. It was also timed with a religious day that brought droves of Sikhs to Amritsar. Though the precise casualty count has never been clear, many hundreds of civilians died in the siege, according to estimates by journalists who covered it.

Four months later, in retaliation, two Sikh bodyguards shot and killed Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in the garden of her residence in Delhi. The assassination unleashed a government-sanctioned campaign of retribution against Sikhs across India. Marauding bands went from neighborhood to neighborhood, voters lists in hand, targeting Sikhs’ homes for arson or killing them in the streets. India’s Supreme Court estimated the death toll at nearly 3,000.

Before Blue Star, Bhindranwale was a fringe figure who appeared in public wearing a bandolier and, in the manner of the medieval gurus, holding a long steel arrow in one hand. His followers had practiced terrorism for years, massacring civilians; assassinating police, journalists, and politicians; and, on one occasion, hijacking a plane. But the insurgency intensified after Blue Star and the anti-Sikh riots, and support for it grew among ordinary people. The decade that followed saw a bloody terrorist campaign by separatists. In two infamous attacks in 1987 and 1991, Khalistani fighters boarded a bus and a train, respectively, rounding up and shooting Hindu passengers.

Buta Singh grew up during the worst of the fighting. He said his family never participated directly in the insurgency, but his mother and other relatives were involved in political parties sympathetic to the cause. When Singh was 10, an older cousin was dragged from home by police and never seen again. This was not unusual for the times. The centerpiece of the state’s repression of the insurgency was a campaign of disappearances abetted by the Indian government’s decision, in 1988, to suspend the article of the constitution protecting due process.

Police rounded up suspected Khalistanis, tortured and killed them, then dumped their bodies in rivers or burned them a half dozen to a funeral pyre. “When the government was questioned about ‘disappeared’ youth in Punjab, it often claimed they had gone abroad to Western countries,” reads one report from Human Rights Watch.

The police regularly came to town to question young men and boys, and they began to pay special attention to Singh.

There has never been a full accounting of the disappeared. Ensaaf, a human rights research group focused on Punjab, estimates that 20,000 people suspected of collaborating with the insurgency vanished or were killed between 1984 and 1993. Of his cousin, Singh says, “Maybe he’s dead. I don’t know. Nobody knows.”

By the time Singh entered his teens, the state had all but stamped out the brushfire of the Sikh rebellion. The police went to great lengths to keep Punjab pacified. On a regular basis, Singh said, groups of officers arrived in his village, took over the temple loudspeaker, and summoned all boys older than 15 to a public place for interrogations.

Singh’s worldview was shaped above all by his mother, a pious Sikh who inculcated him with a deep spirituality and a strong sense of religious nationalism. As a teen, Singh began to spend a lot of time with an “uncle,” a close friend of his father’s, who had the job of reading aloud from Sikh scripture in the gurdwara, or temple. When Singh was around 17, this uncle, like his cousin years before, was taken from his home by police. Unlike his cousin, Singh said, they found the body a few days later in the forest.

Singh took over his uncle’s job in the gurdwara. When he went to college, he focused his studies on Sikhism, and he started going to rallies of the Shiromani Akali Dal Mann, a radical Sikh-centric party. As they always had, the police regularly came to town to question young men and boys, and they began to pay special attention to Singh.

One afternoon, after a police officer had screamed threats in his face, Singh asked his mother for advice. She was proud of him but suggested that he keep his politics under wraps for the time being. “You are a child,” she said. “Focus on your studies.”

Singh’s graduation from college in the early 2000s coincided with the beginning of the slow collapse of Punjab’s agricultural sector, the linchpin of its economy. Punjab has historically been called India’s breadbasket; though it occupies only 1.5% of India’s land, it produces 20% of its wheat.

In the decades before the collapse, Punjab owed much of this fertility to the Green Revolution of the 1970s, which introduced technologies that quickly multiplied yields. But the revolution was unsustainable, relying on massive quantities of nonrenewable groundwater and pesticides that steadily eroded the quality of the soil.

Singh watched as more and more families around him lost their harvests. His father’s farm, by luck, retained good soil and access to water, so Singh worked the fields. He dreamed of being a teacher but, try as he might, couldn’t find work. Disaffected, he ramped up his involvement in the Shiromani Akali Dal Mann, this time with his mother’s encouragement.

In 2004, police began to show up to his house. In a sinister line of inquiry, they would calmly question Singh and his parents on the whereabouts of the cousin who had disappeared 12 years prior.

Singh fled the country. He paid smugglers to sneak him into Greece, where he spent four miserable years working on a vegetable farm on the outskirts of Marathon. He had no legal status and rarely left the plot of land where he lived and worked. In 2008, figuring that he’d been gone long enough for the police to cool down, he returned to India.

“There are areas in Punjab where the heads of multiple households within a village will have committed suicide.”

Things at home, he found, had gone from bad to worse. Heroin was pouring in across the Pakistani border, compounded by synthetic opiates, and the drugs found willing users among young Sikhs crushed by widespread unemployment. There is a neighborhood in Amritsar known as the Village of Widows because so many of its men have died of overdoses. Singh and many other Sikhs say that corrupt local officials ignore or profit from the crisis, and several politicians and police officers have been implicated in the drug trade.

In the meantime, more and more farmers were killing themselves, stricken by crop failure and debt. “There are areas in Punjab where the heads of multiple households within a village will have committed suicide,” said Supreet Kaur, an economics professor at Columbia University.

Singh watched as many of the people he grew up with became lost in the drug trade, whether as users or pushers. Among the youth, many of those who didn’t succumb to addiction embraced an increasingly indignant politics of Sikh purity. Punjab’s youth were drifting apart, the dissolute and the righteous, and the distance between them grew.

On the evening of Dec. 27, 2011, Singh returned to his tiny village in the foothills of the Himalayas after a long day at a political rally organized by the Shiromani Akali Dal Mann. Singh was 28 then, tall and even-keeled, with large, expressive hands. His profile had been rising in the party, and he was now helping them recruit youth members and organize events.

Minutes after walking into his house, Singh said, while he was standing in the kitchen and drinking a glass of water, there was loud banging on the door. Singh’s mother quietly ushered him into his bedroom and locked it from the outside. From a knothole in the wooden door, Singh could partially see what was happening in the living room. Three uniformed policemen burst into the house, he said, accompanied by two men in civilian clothes. Singh recognized some of the officers: A few weeks prior they had stopped him on a country road, roughed him up, and told him to steer clear of any rallies.

Now, Singh’s mother, who was frail with liver cancer, stood in front of them with her hands clasped, saying her son wasn’t home. An officer pushed her to the floor. Singh could see her lying there, too weak to get up.

Singh’s younger brother, a 27-year-old with a mental disability that gave him the intellect of a small child, had been watching with alarm. One of the officers approached him holding a pair of pliers. Singh saw the policeman grab his brother’s hand. As soon as he heard the screaming, Singh started banging on the door.

The officers yanked Singh out of the room. They asked him why he had gone to the rally when they had warned him not to. With his mother on the floor and his brother weeping, Singh heard the officers say that they wouldn’t warn him again, but not before one of them slammed him between the eyes with the butt of his rifle.

The next day, Singh’s mother pleaded with him to back away from the party. He reluctantly kept a low profile for several months.

On March 29, 2012, police opened fire on Sikh demonstrators in the Punjab city of Gurdaspur, killing an 18-year-old engineering student. Party leaders told Singh that they needed him — he had a way of speaking to the youth, converting them to the cause, and this was a time to show resilience.

On the day of an important harvest festival, Singh rode his motorcycle into town and took a bus chartered by the party to Amritsar. The rallies that day were tense. As he returned home at night on his bike, Singh said, a police jeep and two unmarked sedans blocked his way on a dark, secluded road. Eight men got out, four in police uniforms and four in civilian clothing. They pulled Singh off his motorcycle and kicked it to the side of the road.

“You’re coming from Amritsar, ah?” a policeman asked. Singh didn’t lie. Three men stuffed him into one of the sedans while another picked up his bike. They tied his hands, gagged and blindfolded him, and drove three hours to an empty farmhouse in the hills. They brought Singh inside and tied him to a narrow wooden bed. By then it was nearly midnight. The men conferred until four of them left. “Don’t let him sleep,” one of the civilians said on his way out the door.

The remaining four sat on chairs, Singh said, and passed around a bottle of whiskey. The heat that night was suffocating, and Singh asked for water. One of the men stood up and, laughing, urinated on his mouth. This, Singh says, marked the first night he ever found himself wanting death. For several hours, the men did things to Singh that he asked not be put in print.

For several hours, the men did things to Singh that he asked not be put in print.

At dawn the next day they traded shifts with the men who had left the night before. They brought Singh outside and tied his hands to a branch hanging over the farmhouse well. Singh was delirious. One of the policemen took a sharp blade and made a series of shallow incisions on the inside of his left wrist, then rubbed powdered red chili into the wounds and stuffed handfuls in his mouth. Singh blacked out.

(Singh’s accounts of torture are difficult to corroborate fully. This story is based on extensive interviews with him, along with asylum and other immigration documents. Singh has scars that match the incidents he described, including one between his eyes where he says he was struck by a rifle butt and several parallel scars on his wrist where he says he was cut. Singh provided a copy of his ID card for the Shiromani Akali Dal Mann, and rights groups have documented harassment and torture against separatists. Torture by police across India is a widespread, documented problem.)

Singh awoke that night inside, he said, to a new police officer splashing water on his face. The rest of the men were passed out around the room, and the bottle of whiskey was empty. The officer lifted Singh to his feet and slowly walked him about a half mile down the road, where his father was waiting. Weeping, Singh’s father explained how he had scraped together the 3 lakh — roughly $4,500 — that the police had demanded for his release.

Within a few days, Singh said, he fled to the city of Agra to live with his sister. During the three months he stayed there, his mother’s cancer turned critical. While his sister went back to Punjab to help care for her, Singh stayed behind, afraid to return home.

The call saying his mother had died came on Sept. 5, 2012. In Sikhism, it is important for the oldest son to cremate the body of a parent, so Singh snuck back into Punjab to light the pyre. He returned to Agra that night without stopping at home.

The man in the parking lot of the New Delhi airport had muscular arms, a big gut, and a shaved head. He went by Baba. Singh showed up carrying new ID cards with pictures of his younger, beardless self, and Baba handed him the rest: plane tickets and a passport stamped with a one-month tourist visa to Suriname. He told Singh to go straight to the short, dark-skinned teller at the window farthest to the right — no one else.

Singh disappeared into the airport crowd. That morning in April 2013, he hadn’t known where exactly he was going, only that this was the first leg of a journey that would take him to America and that, his father would later tell him, cost $40,000. Singh knew nothing about Suriname, including the fact that nearly a third of the tiny South American country’s population is descended from contract laborers imported from India in the 19th century. So when he got off the plane, he was puzzled to find a man, immediately recognizable as Indian, waiting for him.

Singh approached him eagerly. “Sat sri akal,” he said in greeting: God is the truth.

“Hello,” the man said, curtly and in English.

They climbed into a beat-up white car that shook violently the whole way out of Paramaribo and into the rainforest, arriving finally at a rickety, single-room wood structure. The next morning, the man from the airport showed up with a pair of scissors and cut Singh’s hair and beard.

Singh would spend a month in that safe house, in the company of another young Sikh, never seeing the outside except for a rectangle of sky where the wall met the ceiling. In the ensuing weeks, as Singh made his way up through Central America, he was unable to shake the lifelong habit of bringing his hands to his head to tuck in the folds of a turban that was no longer there.

Indians have recently been taking arduous migration routes through Central America in much larger numbers, feeding the growth of a highly lucrative smuggling industry. Each smuggling network includes travel agents, document forgers, drivers, and, perhaps most important, corrupt government officials such as police officers and customs agents. “You have people playing different roles who come together to accomplish a specific goal, like moving a particular load,” said William Ho-Gonzalez, a federal prosecutor who has helped bring cases against smugglers focused on Indian nationals. “It’s quite effective.”

Midway through his journey, after spending 15 hours holed up with two Nicaraguan migrants in the pitch-black, suffocating bed compartment of an 18-wheeler, Singh was bundled onto a commercial bus. He didn’t know where he was until a handful of military police officers climbed on board and Singh saw that their shoulder patches said “Honduras.” When he and the two Nicaraguans were unable to show papers, the officers arrested them. A well-built, friendly cop in his twenties spoke to Singh in English — the first time in many days Singh had had a conversation with anyone. “We know you’re going to the United States,” he said. If Singh gave him $5,000, he would make sure he got there.

After Singh and the two migrants spent a whole day in a jungle safe house, guarded by teenage-looking cops with assault rifles, the English-speaking officer showed up to say he had connected with their “agent,” and they were free to move on. A new guide showed up and led them on a nighttime trek through the jungle, during which, unbeknownst to Singh, they crossed the border into Guatemala.

In the weeks that followed, Singh spent countless hours hiking through rainforests, riding in cars, trucks, and buses, and, on one occasion, clambering alongside dozens of other migrants onto a shallow boat that Singh was convinced would sink. He eventually made it to Mexico City, where his smugglers put him up in an apartment near the airport. Singh couldn’t sleep, even though the apartment was more comfortable than anywhere he’d been until that point in the voyage. He spent the night sitting by the window, watching the endless loop of commercial airliners ascending, descending, and ascending again.

The next night, Singh boarded a bus that took him to Ciudad Juarez, just across the border from El Paso. There, he spent about a week in a threadbare motel that he would later learn was about 10 minutes from the border.

Finally, on the morning of June 16, 2013, he received a visit from the last of his smugglers, a husky woman in her fifties who had a boyish haircut and chain-smoked cigarettes. She drove Singh to a parking lot next to a long pedestrian bridge connecting Mexico to the United States.

Singh took off walking north, traffic streaming beneath his feet, his legs numb and his heart pounding under the noon sun.

The U.S. government has reacted with fear and suspicion to the swell of Punjabi migrants at the border. Current and retired officials at the Department of Homeland Security (which includes ICE and Customs and Border Protection) and the Justice Department (which includes the immigration courts) described anxiety over the possibility that the same smuggling networks bringing in Punjabi Sikhs could be exploited by terrorists.

“We have had people from the region become national security concerns, whether from Bangladesh, India proper, or the Punjab,” Greg Twyman, an intelligence analyst at Customs and Border Protection, told BuzzFeed News.

The U.S. government has reacted with fear and suspicion to the swell of Punjabi migrants at the border.

The same smuggling networks are used by people from around South Asia, many of whom receive similarly harsh treatment by American immigration authorities. There are no known cases of terrorists using these networks to enter the United States.

There is also widespread skepticism regarding the asylum claims of Punjabis. “The overwhelming majority of these individuals are economic migrants,” Twyman said. “They are young males seeking their fortune.” Some officials described a general suspicion that smugglers moving large numbers of Indians have evolved to coach migrants in how to plead for asylum once they arrive in the U.S., much like the operations run by Chinese Snakeheads did at their peak in the 1990s.

“I call them the designer claim of the month,” said Bruce Solow, a retired immigration judge. “Word gets back to similarly situated individuals — 'Oh, if you say X, Y, and Z in the courts they’re going to believe you.' Then you get the copycat cases, and every damn case coming down the pipe is the same story and fact pattern.”

Officials also said they believe the smuggling networks extend into the United States, helping get new migrants out of detention and facilitating their disappearance as undocumented workers within the country. The two retired ICE officials interviewed by BuzzFeed News said these combined suspicions account at least partially for the agency’s tendency to deny Indians parole. One official described this as a decentralized policy: She was unaware of it while working at ICE headquarters in D.C., but it was clear when she worked in a field office near the border.

Although ICE did not comment specifically on Buta Singh’s case, these suspicions may explain why he, along with every other Sikh arriving in the El Paso Processing Center between 2013 and 2014, was denied parole.

The morning after Singh turned himself in at the border, he was moved to the El Paso Processing Center, which holds roughly 800 detainees at a time. Within a few weeks, he had passed his credible fear interview, which is used to determine whether an asylum-seeker can stay in the U.S. and proceed with a claim.

Singh had submitted detailed paperwork, including birth certificates from India, showing that his sister and her husband, both naturalized U.S. citizens, lived outside Seattle and could ensure his appearance in court. Nevertheless, ICE denied Singh’s release, asserting in its paperwork that he had “insufficient ties to the community.”

Few in the Sikh diaspora would deny that violent police repression has died down significantly since the height of the insurgency, or that many young Sikhs are driven to the U.S. by economic, not political, reasons. But there is still a sense that the U.S. has failed to keep up with the reality in Punjab. One Sikh lawyer in the United States, who asked to remain anonymous to protect relationships with government officials, pointed out that the Canadian government gives its immigration authorities relatively detailed reports about modern-day police repression of Sikh politics, whereas the U.S. does not. “I’ve sat down with officials from the State Department and informed them of these things,” the lawyer said, to no avail.

Police still keep close tabs on families considered to be tied to the separatists or any other “progressive Sikh agenda,” said Sukhman Dhami, co-founder of Ensaaf, the research organization devoted to documenting human rights violations in Punjab. This regime is in many ways indistinguishable from the one that disappeared thousands of people 20 years ago, and operates with impunity, Dhami said.

For instance, Sumedh Saini, the current head of the Punjab police, occupied a senior position in the same force during the '90s and has been directly accused of various rights violations, including some documented by Ensaaf and Human Rights Watch.

Police behavior in Punjab dovetails with a much larger problem: the widespread use of torture by police across India. As the human rights group Minorities of India wrote in a 2011 report, “Indian law enforcement culture overall encourages and often demands that police officers systematically employ barbaric torture methods and extra-judicial killings.” The problem, however, has done little to tarnish India’s reputation as a vibrant and free democracy. Jaspreet Kaur, a lawyer with United Sikhs in New York, recalled interning as a law student for the Indian government in a human rights–related position. At that point, as now, India had signed but not ratified the United Nations Convention Against Torture.

“My first project was to find reasons why we should not ratify this convention,” she said.

Every Sunday evening at 6, the Sikhs in the El Paso Processing Center gathered in a drab meeting room for prayer. Buta Singh usually led the sessions, quoting from the Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikh scriptures, as he had after the killing of his mentor in Punjab. The months dragged on, and ICE continued to deny parole or bond hearings to every Punjabi in El Paso. Singh knew of only one Sikh at the detention center who was granted bond.

The young Sikhs began to use their prayer meetings to organize, and after a couple of weeks of argument, they decided to stage their hunger strike. They picked April 8, 2014, and that morning refused to leave their bunks for breakfast.

As the days wore on and a few Sikhs began needing urgent medical attention, Singh sensed that some of the staff at the detention center were getting nervous. For some reason, perhaps because Singh spoke English, ICE had pegged him as the ringleader, even though he says that the group made decisions unanimously. ICE officials spoke to him every day, and every day he reiterated their demands: Either express a willingness to grant the detainees parole or bond, or move their cases elsewhere in the country.

That morning, they refused to leave their bunks for breakfast.

Then ICE brought in N.P.S. Saini, the diplomat from the Indian consulate in Houston. When Saini told the Sikhs that the U.S. wouldn’t want them because they weren’t doctors or engineers, one detainee, who spoke to BuzzFeed News on condition of anonymity, replied that he had in fact been studying engineering in India before he left.

Saini, according to Singh and four other detainees who were present for the exchange, switched from cajoling to veiled threats. He told the young men that many of their peers had come to the United States only to be jailed there, then returned to India, where they were jailed again for leaving. He reiterated that authorities in India now knew where they were. In the days after the visit, Singh and two other detainees said their families received threatening phone calls from police.

“ICE routinely grants access to consulate officials to visit nationals of their country in ICE detention,” an agency spokesperson told BuzzFeed News. “On this specific visit, all detainees met with the consulate official voluntarily.”

Attorney John Lawit, who handles Singh’s case as well as those of several other El Paso detainees, said that ICE’s decision to bring in Saini — or at least to allow his visit — violates the U.S. Code of Federal Regulations, which protects the confidentiality of asylum-seekers, specifically to avoid outing them to the authorities or other entities they’re fleeing. Shortly after the visit, Lawit filed complaints with the inspector general of the Department of Homeland Security, who dismissed one complaint and has yet to resolve the others.

On April 25, 2014, speaking to India Abroad, a representative of the embassy confirmed that consular officials had visited the detention center. The consulate and the Indian Embassy in Washington did not respond to numerous emails and phone calls.

The day after Saini’s visit, Singh was pulled out of his unit and left to sit in an isolated room. After a few hours, two ICE officers came in and put a tray in front of him with a sandwich and some juice. They told Singh that all the other Sikhs had relented and were already eating. When Singh said he didn’t believe them, they left him alone in the room with the tray for a few hours. Singh didn’t eat.

When the officers came back, they had a higher-ranking ICE official with them, who told Singh that they were willing to negotiate: If the Sikhs called off the hunger strike, ICE would begin slowly moving their cases to other parts of the country, where they would get another chance at parole and bond hearings. That night, Singh and the others decided to eat.

Within a couple of weeks, Singh’s case was transferred to the detention center in Tacoma, Washington. A week after that, the ICE office there granted Singh a $7,000 bond, and his family paid the money.

Singh was released on May 28, 2014. His sister and brother-in-law were stuck in traffic on the way to pick him up, so he stood and waited outside. It was raining, and a security officer told Singh that he could stand inside if he wanted.

“No, no,” Singh said. “It’s good.”

The gurdwara in Kent, Washington, where Buta Singh now lives, is one of the largest Sikh temples in the Seattle area. It has a tall flagpole out front wrapped in cloth the color of saffron — a revolutionary color, connoting emancipation. At the base is a plaque dedicating the flagpole to the martyrs of Operation Blue Star in 1984.

In the temple’s basement on a weekday evening in October, people sat on the floor eating vegetarian food from cafeteria trays. It is an indispensable feature of every gurdwara that anyone who enters may eat a full meal for free. Every wall of the basement was adorned with framed images, some of them taken from illustrated books. The majority marked moments of violence throughout Sikh history. One depicted “The Great Holocaust,” in 1762, with Mughal warriors on horseback trampling the piled bodies of Sikh peasants. Another showed an early martyr sitting placidly in a boiling cauldron of water.

On the other end of the room, someone had put up a series of color printouts of photographs from recent unrest in Punjab. In one village, police opened fire on protesters. The photos showed various gory scenes: men being loaded into ambulances with blood pouring down their faces; a man lying on his side, his back pockmarked with buckshot.

Upstairs, on the main temple floor, a scattered handful of visitors sat on the carpet of a large, dim room. Singh knelt facing the front, where a massive copy of the Guru Granth Sahib rested open on a platform festooned with colored lights. To the side, three musicians played a droning, sinuous raga on two harmoniums and the tabla.

This, Singh said, is the first place he went after his sister picked him up from the detention center in Tacoma. He sat and prayed for almost four hours before he was ready to see his new home. It was the first time in years he’d felt peace.

CORRECTION

An earlier version of this article misidentified Amritsar as the capital of Punjab. The capital of Punjab is Chandigarh.