Most twenty-somethings will never belong to a union — and may never know anyone who does. But many are in need of a job, and many more are sitting on student loans, which total more than $1 trillion nationally. And now, plenty are favoring a presidential candidate who identifies as a democratic socialist.

The Future We Want, a new collection of essays by and for this demographic looks at the future of organized labor and the left, with debt strikers, Black Lives Matter, and other movements leading the way forward. BuzzFeed News spoke with the collection's editors — Sarah Leonard, a senior editor at the Nation, and Bhaskar Sunkara, the founder of political quarterly Jacobin.

Given that a lot of people in our generation may never belong to a union, how do you see them engaging with the labor movement?

Sarah Leonard: We’ve definitely seen the fits and starts of organizing of a generation that didn’t grow up with unions. But one of the reasons the Sanders campaign is so successful is because a number of movements have laid the groundwork for thinking about problems socially. And that’s a bigger change than sometimes we remember today.

A number of years ago, a Tumblr got started that allowed people to post their debt online. People would share photos of themselves, often with a piece of paper over their faces, saying, "I have this much medical debt. I have this much school debt. I’m really ashamed." It brought people together in a way that literally allowed us to view their debt as collective — in one big stream. Whereas before everyone thought that they were doing something wrong, that they’d screwed up somehow, that they were stupid. And that’s a really insidious feeling.

You’ll never struggle over something you feel you deserve to suffer. But if you feel like this is a social problem that has been unfairly, structurally imposed on society, then you have something to fight over.

Bhaskar Sunkara: The only maybe downer note I’ll add to that is — it’s not even just a matter of raising consciousness. Most people, let’s say, don’t try to start a union not because they’re not aware of this as an option. But also because they’re just too smart to try to start a union.

We’re in an era where there’s high real unemployment, and there is not a strong labor movement. Say you manage to be stably employed — your best bet is often to try to keep your head down, and if you need to cover any debts, you’re going to go to your friends, your family, or maybe you're going to take out some credit card debt. That’s often a more viable route.

So I think we need to understand how much the deck is stacked against ordinary workers. Not to be defeatist, but to take stock of the number of steps it will take to get to a point where collective action is going to be a viable thing for most people.

The collection focuses on the relationship between race, gender, sexuality, and class. Could you talk about the book's intersectional lens on the labor movement?

SL: People experience the lack of power in their lives in many different ways, and it’s important to talk about those experiences so we can do coalition-building — to be able to say, "I feel ground down by my boss, but you also feel ground down by the police, and for you those are equivalent problems."

BS: Often I think this kind of stuff is poorly labeled identity politics, in a dismissive way. I think it’s better to call it the old-school way: anti-oppression politics. One thing the book drives home is that any viable anti-racist or anti-sexist agenda has to have a class component. That’s not to say that just class is enough, but if you try to present an anti-racist or anti-sexist program without class, it’s definitely not enough.

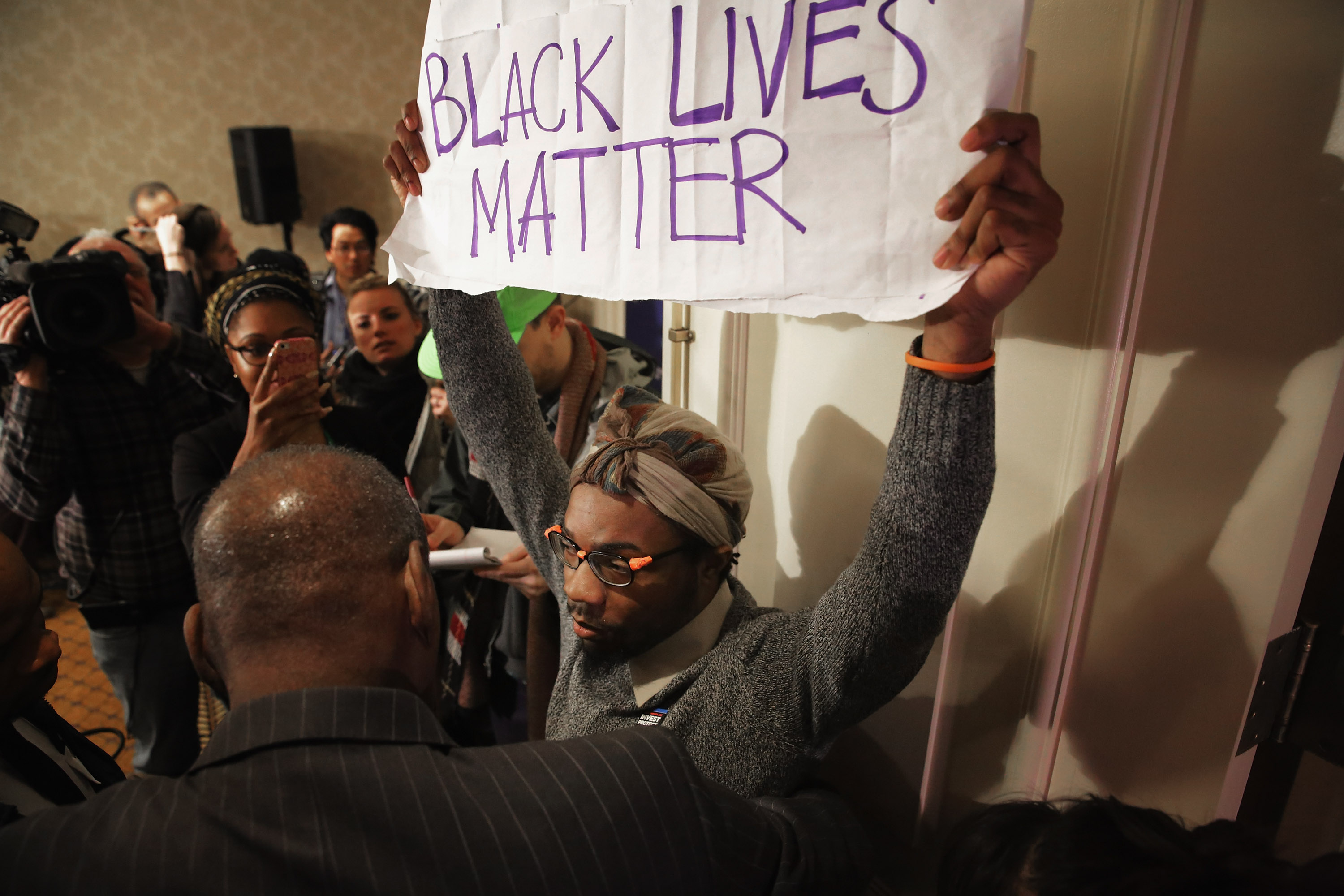

SL: A social justice unionism can mean collaborating with all kinds of movements, such as Black Lives Matter. The Black Youth 100 Project put out a big report recently on the role of black workers in the labor movement, for example, because black people in this country have more trouble building wealth. It’s harder to get a mortgage, for instance, and people of color are more likely to suffer in times of layoffs.

SL: The way that the candidates have had to address the issues raised by Black Lives Matter has also been extremely significant. That’s partly because they’ve declined as a movement to endorse anyone, they’ve taken away candidates’ microphones and made public relations nightmares for them when they failed to address issues affecting black and brown people in this country.

At the last Democratic debate, the candidates were competing to be most progressive on mass incarceration and criminal justice. The effect of that movement on the campaigns has shown how movements should use campaigns. We have a group of the leaders of Black Lives Matter having a conversation in the book — addressed specifically to the police but also to larger criminal justice questions.

The book also talks about what the labor movement can do to help combat climate change.

SL: We thought that was crucial. If the context of our politics in the future is the fact that our world is melting, we have to have a strategy for dealing with that which incorporates the critique we’re already making of how burdens often fall on the poor.

BS: Part of it is also trying to push against the notion that "this is what happens when civilization gets too complex, and we start polluting more often," — like your average worker owns a coal power plant. So on the one hand it’s pushing against the idea that we’re all responsible, while also saying that any solution should be in the interest of the vast majority.

The book primarily deals with domestic issues. How do you see it as informing or being informed by movements outside the United States?

SL: We’ve seen a number of upsurges in other countries. Corbyn is a good example. Syriza in Greece. Podemos in Spain. The Left party in Portugal. People are suffering, and so people want left-wing governments. They’re like, "Get us out of here."

But the forces are not really strong enough to support a stable left-wing program. So we're engaging in a learning process. What we’re trying to do with this book and elsewhere is think, "What if we might actually win?" This is not the full policy brief for a socialist presidency, god knows. But we’re doing our best. The important thing is to stop thinking of yourself as a perpetual critic and start thinking you might actually have an opportunity to begin implementing these things.

On that note, there’s pragmatism to the book, but there’s also some radical thinking. Why is it important to sometimes think in utopian terms?

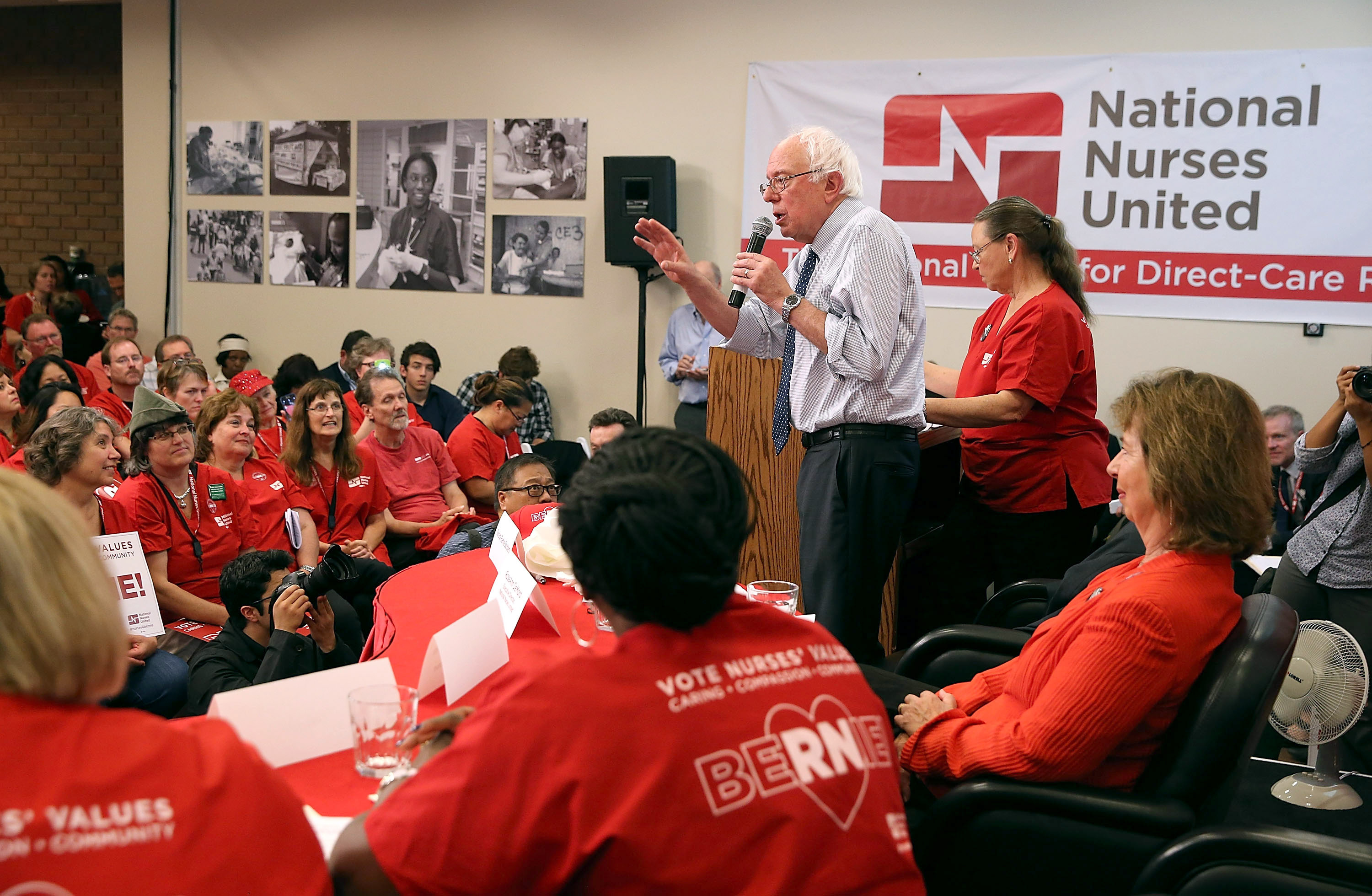

SL: Bernie Sanders sounds idealistic to some people and pragmatic to other people. If you have no union, low wages, and no healthcare, he sounds pretty pragmatic. Because when people say, “He’ll never be able to get anything done, and there will be blood in the streets before a Sanders agenda can pass,” — well, there’s already blood in the streets. We have high infant mortality compared with Western Europe. I was talking to a woman from the nurses’ union and she said, “When people come into the intensive care unit where I work, the first question out of their mouths is about how they’re going to pay for it.”

BS: Beyond that, let’s say this was a race between radical reforms offered by Sanders and incremental reforms by Clinton — if you have a Republican congress constituted the way it is now, the incremental reforms aren’t going to pass anyway. So would you rather spend that capital getting insufficient reforms through, or would you rather put forward a politics that can build its own social base? And Sanders has actually uncovered a large constituency that had felt left out of the political process.

People are ready for something radical. They want enemies named, and they want proposals put forward they aren’t used to. And it’s really up to us and to people like Sanders to put forward these proposals, because if they aren’t put forward by us, they’re going to be put forward by the Trumps of the world.

Similarly radical, but in the opposite direction.

BS: Right. I also think a lot of what is going on now with socialism is kind of a mile-wide but an inch deep. We need to take advantage of the moment and talk to as many people as we can, but also be aware of our own marginality.

I feel the same way about Jacobin. We’re growing quite fast by the standards of a socialist publication, and we think we can ride the Sanders wave to above 20,000 subscribers. But at the same time, that’s the old feeling of, “We have five people in a group. Two months ago, we had one. Therefore, at this pace, in a hundred months, we’ll be a mass party.” It doesn’t actually work that way.

SL: We did want to be somewhat pragmatic with the collection. There’s nothing in there that’s unimaginable: universal child care, paying people to do jobs that are not creating climate change. These are not things that should be impossible to conceive of, even in the relatively near term, should the political will exist.

We didn’t want to call it a blueprint because we’re aware that any solutions are the result of people’s struggle. That struggle is something we’re seeing right now, and so we would not presume to say, "The outcome should be 'x.'" That’s not our place. Our place is to contribute to that movement by putting forward things that we can agree to struggle for — and expanding our imagination as to what those things might be.

What led you two to this place — to your politics and to be editing this collection?

SL: I grew up a Democrat with liberal parents. And what became frustrating was, Democrats always seemed to be half-assing it. So they’d say, "we want to redistribute — some." But it always seemed to be picking at the edges. So I started moving away from those politics and then started working at Dissent, which is a long-standing political quarterly that identifies as democratic socialist. Which is a word that people understand now.

BS: My parents were immigrants who came to the country in 1988, the year before I was born. So my first couple years, as one would imagine, there was a lot of moving around. My dad, who was a professional overseas, was de-classed, for lack of a better word. He was just always working. My mom didn’t finish her high school education, so she was working as telemarketer and did lots of other jobs.

I’m the youngest of five, and it’s impossible to think that the fact that I was able to pursue what I wanted to do and go to college was anything more than an accident of birth and circumstance. To the extent our family situation got way, way better it was just because both my parents got public sector jobs. So if I was going to develop any political consciousness at the very least it would be a broadly social-democratic, liberal sentiment that understood that value of public sector work and public goods.

What do you say to older critics who may take issue with your age and relative radicalism?

SL: If they didn’t want bunch of radical twenty-somethings, they shouldn’t have created a system of massive college debt. And no healthcare. That's on them.