After working underground in the coal mines of southern West Virginia for almost 35 years, Steve Day thought it was obvious why he gasped for air, slept upright in a recliner, and inhaled oxygen from a tank 24 hours a day.

More than half a dozen doctors who saw the masses in his lungs or the test results showing his severely impaired breathing were also in agreement.

The clear diagnosis was black lung.

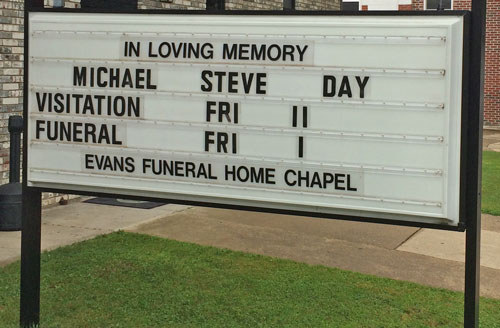

Yet, when I met Steve in April 2013, he had lost his case to receive benefits guaranteed by federal law to any coal miner disabled by black lung. The coal company that employed the miner usually pays for these benefits, and, as almost always happens, Steve’s longtime employer had fought vigorously to avoid paying him. As a result, he and his family were barely scraping by, sometimes resorting to loans from relatives or neighbors to make it through the month.

Like many other miners, he had lost primarily because of the opinions of a unit of doctors at the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions that had long been the go-to place for coal companies seeking negative X-ray readings to help defeat a benefits claim. The longtime leader of the unit, Dr. Paul Wheeler, testified against Steve, and the judge determined that his opinion trumped all others, as judges have in many other cases.

Today, however, there is final and overwhelming evidence that Wheeler was wrong: Steve’s autopsy.

On July 26, what was left of Steve’s lungs gave out. He was 67 years old. The doctor who performed the autopsy found extensive black lung. With the permission of Steve’s family, I shared his autopsy report with three leading doctors who specialize in black lung and related diseases. Each said essentially the same thing: Steve had one of the most severe cases of black lung they had seen.

“A majority of his lungs had been replaced by scar tissue with coal dust,” said Dr. Francis Green, a professor of medicine at the University of Calgary and one of the world’s top experts on the pathology of black lung.

Dr. David Weissman, who heads a federal agency’s division that certifies doctors — including Wheeler — to read chest X-rays, said it was “very concerning” that a certified reader would fail to recognize a case as severe as Steve’s.

Reached by phone, Wheeler said, “I’d love to talk to you, but the hospital has asked that everything be referred to the legal team.”

A Johns Hopkins spokesperson would not comment on Steve’s case, but noted that the black lung X-ray-reading program headed by Wheeler has been suspended, pending an internal review. The spokesperson refused to provide details about the review, saying only that it “is proceeding as rapidly as possible, and I can assure you that Johns Hopkins takes it very seriously.”

Eight months before he died, Steve filed a new claim for benefits, presenting evidence that the masses in his lungs had grown and his breathing had worsened even further. He underwent an exam by a doctor of the company’s choosing, and even this physician found severe black lung.

In late September, a Labor Department claims examiner issued an award of benefits. But this is only a first step in what is usually a protracted process of appeals. Indeed, Steve also had won at this initial level in 2005. The company that employed Steve, now a subsidiary of Patriot Coal Corp., appealed that decision, leading to the denial of the claim by a judge.

Patriot refused to say whether it would continue to fight Steve’s current claim. “Patriot Coal follows set procedures in the handling of claims,” a spokesperson said in a statement. “We will continue to follow our procedures and will respond accordingly.”

I asked whether, given the overwhelming autopsy evidence, the company would be willing to concede that Steve had a legitimate claim for benefits. “We have procedures we follow in reviewing a claim, and we will follow these procedures with this claim, as with all others,” a spokesperson responded. She would not say what those procedures are.

Paul Frampton, an attorney at the firm Bowles Rice LLP, handles a large number of black lung cases on behalf of coal companies and defeated Steve’s previous claim. He is again representing Patriot Coal in the current claim. He did not respond to repeated voicemails and emails.

Steve became the face of a series of investigative stories I wrote last year while at the Center for Public Integrity; the series logo featured an image of him holding his hardhat with tubes feeding oxygen through his nostrils. He freely shared his story, granted me access to deeply personal records, and became a symbol of the struggles many other miners face.

Now his autopsy report and his personal story highlight how Wheeler’s approach to reading chest films, applied in thousands of cases over decades, led to wrongful denials — with devastating consequences.

It was 1969 when Michael Steve Day arrived back home in Glen Fork, West Virginia, after a tour in Vietnam, where he had worked base security for the Air Force. He returned amid tumult in the Appalachian coalfields.

A widespread strike had virtually shut down the coal industry in West Virginia, and tens of thousands of miners had descended on the state capitol in Charleston, demanding legislation to address a problem that had plagued miners for more than a century. It had gone by many names, but a movement had coalesced around a simple, descriptive term: black lung.

Later that year, Congress would make a promise to the nation’s miners: Coal companies would be required to control levels of disease-causing dust, an approach meant to virtually eradicate black lung, and anyone who did get it would receive fair compensation.

But at the time, Steve, 23, had romance on his mind. He met a girl named Nyoka Gayle Fortner. They spent afternoons taking walks, holding hands. They’d been together only weeks when Steve asked her to marry him.

“Aw, Steve, you can do better than me,” Nyoka recalled telling him. “No, I want you,” he said. They eloped on July 25, 1969.

Both Steve’s and Nyoka’s fathers had been coal miners. Nyoka had seen the physical toll of the job, and she asked Steve not to go underground. He said he wouldn’t.

But options are limited in southern West Virginia, and the lure of the best paycheck around soon hooked Steve. He went to work for Eastern Associated Coal in September 1969, and he would work the rest of his roughly 33-year mining career for this company that’s now owned by Patriot Coal.

He did the dustiest jobs: cutting coal with powerful machinery, hauling it in shuttle cars, or driving bolts into the roof of a freshly mined area to ensure it didn’t collapse. He’d work double shifts, extra days — whatever he could to earn more for his family.

Steve and Nyoka had three children: a son, Michael Steve Day Jr., and two daughters, Stepheny and Patience. “My dad would come in from the mines, and he’d still be dirty, coal dust all over him. And he would stop and play,” Patience recalled. “I remember many a day when we would be out in the front yard, we would have ball gloves, and he would toss the baseball around with me.”

Jobs came and went with the boom and bust of the coal industry. There’d be layoffs, and Steve would drive around day after day looking for work. And there were the inherent dangers of working in often-unstable caverns deep underground, surrounded by powerful equipment. Rocks slammed into Steve’s back and bruised and split open the skin on his elbows and knuckles. He sometimes worked in tunnels so low that he had to crawl for entire shifts. He’d come home with knees like balloons. “He would work and work and work,” Patience said, “and it was all for his family.”

The more serious problem was less obvious. By the late 1990s, he began to notice coughing and labored breathing. In 2004, Steve’s doctor told him to get out of the mines; his lungs were shot. The man Nyoka had always seen as indestructible, “a superman,” had to retire.

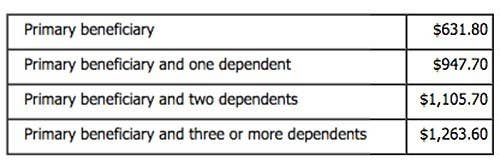

Steve’s case, which he filed in 2005, grabbed my attention for a simple reason: The judge’s 2011 decision denying benefits didn’t seem to make much sense. Continuing to read through thousands of decisions, I came to realize that nonsensical conclusions are surprisingly common in the arcane world of federal black lung benefits.

When a miner files a claim, he is entitled to a medical exam conducted by a doctor approved by the Labor Department, but he also must submit to an exam by a doctor of the company’s choosing.

Steve unwittingly selected a doctor who frequently testifies for coal companies to conduct his Labor Department-paid exam, but even this doctor found the most advanced form of black lung. The doctor chosen by the company also found black lung initially, but he changed his mind after being sent Wheeler’s reports on the chest films.

A miner has to prove not only that he has black lung but also that it has rendered him totally disabled. In Steve’s case, every doctor agreed his lung function was so bad that he was totally disabled, and every doctor except Wheeler and his two Johns Hopkins colleagues saw black lung on the X-rays and CT scans.

But the reports and testimony from the Johns Hopkins doctors were the ones that counted. Deferring especially to Wheeler’s qualifications — multiple professional certifications, undergraduate and medical degrees from Harvard University, a long list of publications, four decades of teaching at a world-renowned institution — the judge found that Steve “did not have” black lung.

There was no evidence that Steve had any of the illnesses Wheeler suggested as alternatives — tuberculosis, bird tuberculosis, or a fungal infection caused by exposure to bird or bat droppings. The judge made no determination about what was causing Steve’s obvious disability, just that it wasn’t black lung.

Reading through other cases, I saw many instances of disabled miners who were being treated for black lung but who, according to judges who based their decisions in large part on the opinions of Wheeler and his colleagues, didn’t have the disease or couldn’t prove they had it. It was as if they had some mystery illness.

In reading Steve’s X-rays and CT scans, all of the doctors more or less agreed about the white splotches they saw; the main difference was how they interpreted them. But the most definitive way to determine if someone had black lung is not to analyze shadows on film but to examine the lungs themselves in an autopsy.

Steve’s diseased lungs, then, provide a useful test of who was right and who was wrong.

Of the reports by doctors who saw black lung on the images of Steve’s chest before his death, perhaps the most detailed was by Dr. John E. Parker, who, for the last decade, has been chief of pulmonary and critical care medicine at the West Virginia University School of Medicine and, before that, ran the X-ray-reading program at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), which licenses physicians such as Wheeler to examine films for black lung and similar diseases. Parker teaches doctors to read X-rays on behalf of NIOSH and the American College of Radiology.

In 2013, I asked him to review Steve’s X-rays and CT scans, telling him only Steve’s name, age, and mining experience, as well as the fact that the interpretation of the films was contested. With the exception of one CT scan, Parker evaluated all the films Wheeler reviewed, as well as some taken more recently. Considering only the earlier films — those also evaluated by Wheeler — his conclusion was clear: Even back then, Steve already had end-stage black lung.

“Mr. Day’s history and findings are so characteristic that I am confident that Mr. Day has lung disease related to his coal mining,” Parker wrote in his report. “I am so confident, that I am indeed certain a biopsy or an autopsy, if performed, would confirm my diagnosis.”

Wheeler, by contrast, had been asked during a deposition in 2009 whether the spots he saw were black lung. “They’re not,” he testified.

How did Wheeler arrive at this conclusion? He has a strict set of criteria that he applies when reading films. Yet medical literature contradicts some of his opinions, and Steve’s autopsy report supports these texts and the reports of Parker and the other physicians who saw black lung.

For example, evaluating a 2005 CT scan, Wheeler noted areas of dead tissue inside the masses in Steve’s lungs and said these are typical of an infectious disease but not black lung. This film was not available for Parker to review, but, in later CT scans, he also saw areas of dead tissue. Consistent with medical literature, Parker said that they could be characteristic of severe black lung. As the disease progresses, areas of lung tissue inside masses can die, become liquid, and sometimes rupture into the airway, causing miners to cough up black phlegm. This matches what Steve and Nyoka described experiencing, and the doctor who performed the autopsy confirmed that this is what was happening in Steve’s lungs.

This pattern recurs in the reports. Wheeler and Parker saw essentially the same things. They more or less agreed on characteristics such as the location of the masses and the prevalence of smaller background spots. Yet Wheeler said these things pointed to tuberculosis or a fungal infection, while Parker said they pointed to black lung. The autopsy report shows that Parker was right and Wheeler was wrong.

The criteria Wheeler applied in Steve’s case didn’t just contradict Parker and other doctors. Many of the standards Wheeler used when reading films are at odds with the definitive text, written by an expert panel of the College of American Pathologists and still in use today, on the appearance of black lung.

Nonetheless, Wheeler has used these criteria in countless other cases. He has recited them in report after report, deposition after deposition. In a system with few attorneys willing to represent miners — and even fewer who know enough to challenge Wheeler’s views — his assertions have carried great weight and contributed to many miners being denied black lung benefits.

In more than 1,500 cases decided since 2000, Wheeler has not found a single case of the most severe form of black lung, even as other doctors saw the advanced form of the disease in 390 of these cases. Overall during that time, which is as far back as digital records go, miners have lost more than 800 cases after other doctors saw black lung on an X-ray but Wheeler graded the film as negative.

And that’s only counting the cases that made it to the second stage in the claims process — a hearing before an administrative law judge — and not cases that were denied at the initial level. Decisions at that early stage are not publicly available. The Labor Department recently contacted more than 1,000 miners who have filed claims since 2001 and were denied after negative readings by Wheeler, informing them that they could seek to reopen their claims or file new ones.

Wheeler has been reading X-rays for black lung for at least 40 years.

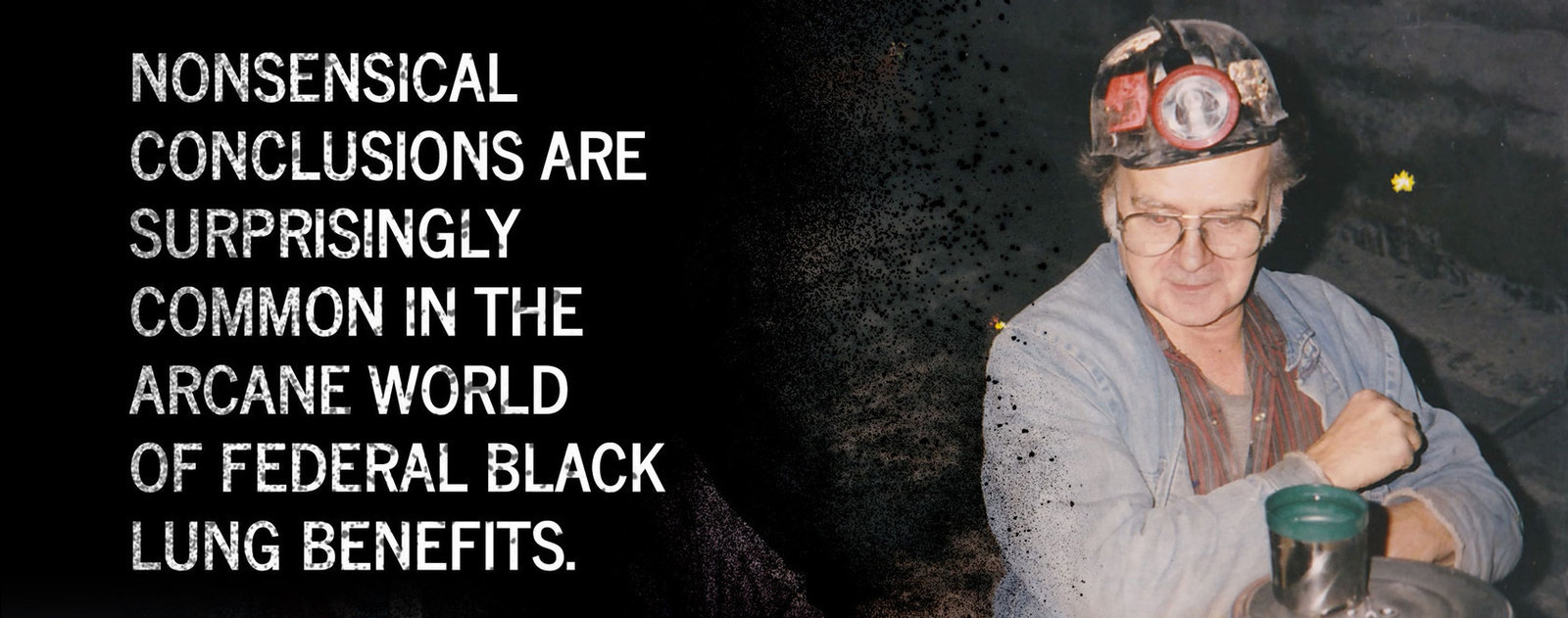

For hours one afternoon in April 2013, Steve and Nyoka sat side by side on the couch in their living room, describing to me the torturous routines that consumed their daily lives.

Steve spent most of his day in a recliner next to his oxygen machine. Most physical activity was out of the question. So was lying down to sleep; if he tried, he’d start to feel suffocated. Every night, Nyoka would sleep lightly in the bedroom nearby, listening to Steve’s breathing. Often, she would hear him gasp or seem to stop breathing altogether. She’d jump out of bed and beat his back until he coughed something up.

Nyoka struggled with debilitating pain from rheumatoid arthritis. Another disease that caused her body to retain too much iron sapped her strength. Also living in the four-bedroom, one-bathroom home with them were Stepheny, Patience, and Patience’s husband and two children.

As we talked that day, Nyoka’s words rose in a crescendo over the steady hiss of Steve’s oxygen machine.

“They spent my husband’s life and now don’t want to give him a penny for it and don’t care anything about the family that will be left behind,” she said, tears streaming down her cheek.

Steve’s expression never changed, and he said nothing. He just reached out a hand and clasped hers.

“To explain Steve is almost impossible,” Nyoka said recently. He was proud of his military service, but, unlike many people in the area, he never liked hunting — couldn’t bring himself to kill an animal. He rarely said much, but, if you pushed the right buttons, he’d become an engaging storyteller. He loved Chevy trucks and brooked no criticism of them, and he doted on a small gray cat, petting her as she purred or slept in his lap. “It was a little precious relationship that they had,” Patience, 30, said recently, laughing.

He adored Patience’s two sons. The first, Eli, now 2, was his “Little Buddy.” The second, Demetrius, now 7 months old, became “Tiny Buddy.” Eli still sees his grandfather in household items. Recently, Patience was stocking the refrigerator with Dr. Pepper, the only soda Steve ever drank (and the one thing he asked for when I visited him in the hospital recently). Eli appeared. “Paw Paw?” he asked.

As Steve pursued his new claim this year, his breathing continued to deteriorate. This July, he ended up in the hospital because of a gallbladder infection. Surgery to remove the organ was a success, but, after coming out of anesthesia, Steve had trouble breathing. For weeks, his family’s hopes rose and fell with a draining series of improvements and setbacks.

July 25 arrived — Steve and Nyoka’s 45th wedding anniversary. For weeks, Nyoka’s rheumatoid arthritis had been so bad that she barely could get out of bed, so she gave Patience a long note to read to Steve.

“She wanted me to wish him a happy anniversary, said that she loved him, she missed him terribly, and that, if her body would have let her, she would have been there,” Patience recalled.

Steve’s eyes were closed, and the bed shook as he fought for each breath. “I was sitting beside the bed in a chair, and I had my arm up on the bedrail and my head bowed,” Patience said. His breathing was so labored, she said, that “my upper body was being shaken.”

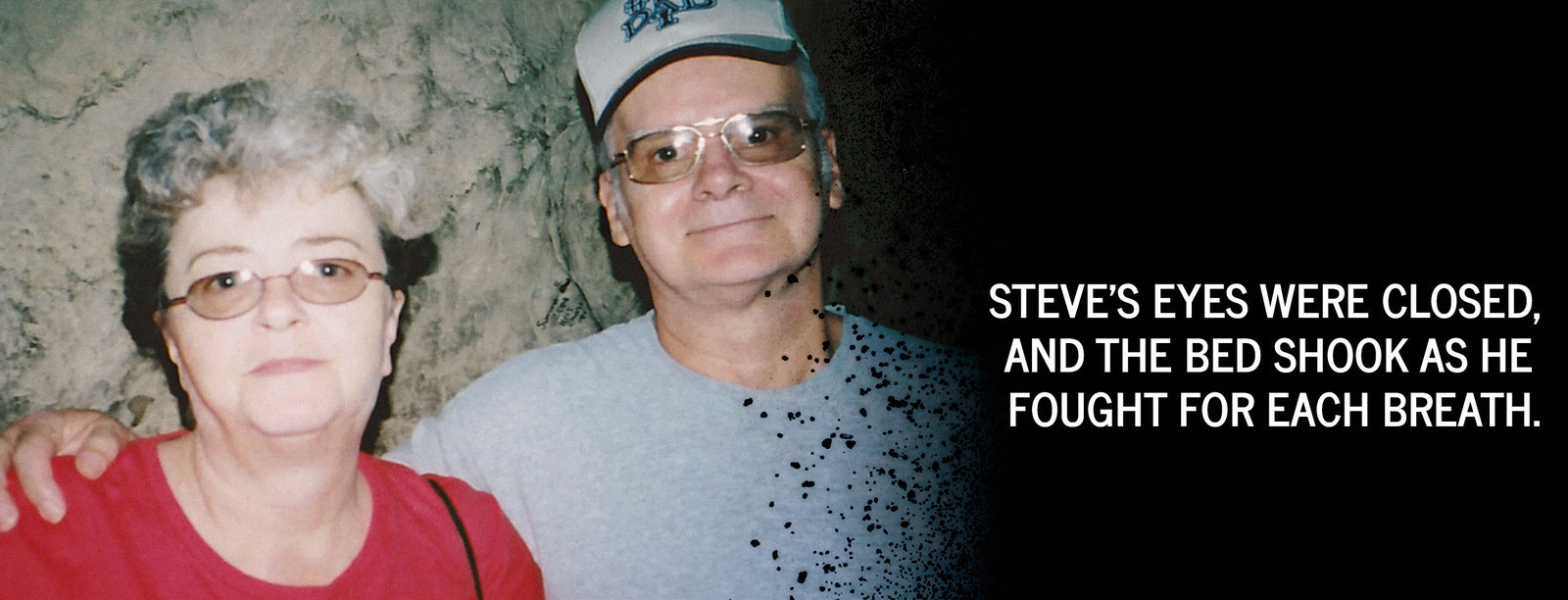

Steve died the next day.

At his funeral, an American flag lay across his coffin, and a collage of pictures told the story of a military man, coal miner, and proud husband, father, and grandfather.

There are many things about Steve I’ll always remember, perhaps most of all a conversation we had last November. It was a Friday evening, two days after the story featuring Steve had come out, and Johns Hopkins had just announced that it was suspending its black lung X-ray-reading program that Wheeler headed.

I called Steve and told him. He let out a hoot of elation unlike anything I’d heard from him before. He gathered his family around the phone. As I gave details, he excitedly relayed them.

Within minutes, though, his restrained tone returned. He asked, “I guess maybe I helped some people?”