WASHINGTON — If any Republican former state attorney general from the South announced his support for LGBT advocates' side of a political issue, the move would make news.

When Mike Bowers decided to do so, it was more than that. For 17 years, Bowers' name was synonymous with the legal inferiority of gay people.

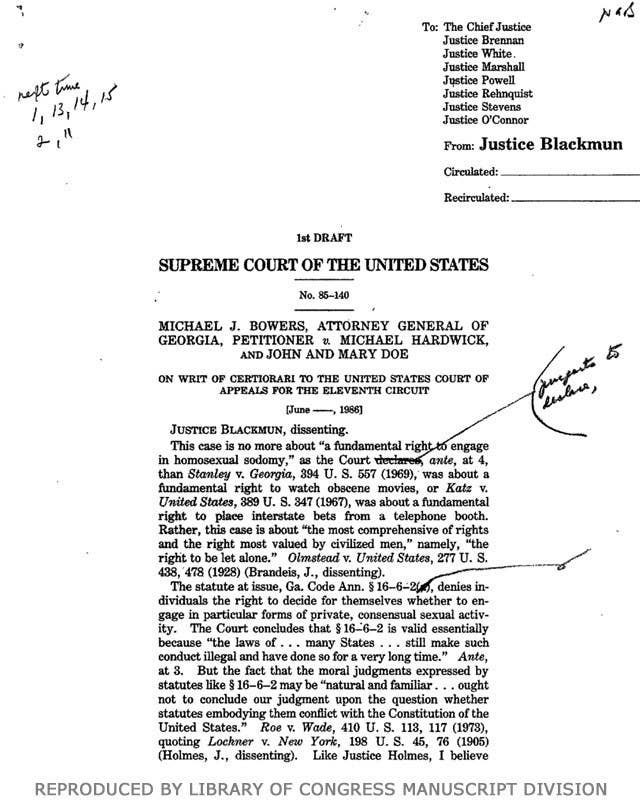

Bowers v. Hardwick, the 1986 Supreme Court decision allowing state bans on "homosexual sodomy," was only before the Supreme Court because Bowers, then the attorney general of Georgia, asked the justices to hear the case and uphold the constitutionality of the ban.

Nearly 30 years later, Bowers says he's "changed as society has changed."

On Tuesday, Bowers released a scathing seven-page memo detailing his legal conclusion that pending "religious liberty" legislation in Georgia — as he put it in an extensive interview with BuzzFeed News — "is an excuse to discriminate."

The proposals, modeled in part on the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act, are "a trend all over the country," Bowers said, and their timing — coming in the wake of this past year's many marriage equality decisions — makes them suspect. The bills provide religious exemptions for laws that otherwise apply to all, but many of the state bills have provided for even broader exemptions that could reach further than the direct government burdens intended to be lessened by the federal law.

As Bowers put it Tuesday, "Any time a person wished to refuse to act in response to a government requirement, he or she could assert the protection of the proposed RFRA." An example, often cited by LGBT advocates in fighting these bills, is a baker who wishes not to bake a wedding cake for a same-sex couple despite state public accommodation protections that include sexual orientation.

Bowers hadn't spent much time considering the bills, he said, until the state's LGBT organization, Georgia Equality, asked him if he would consider taking on an analysis of the ones pending in Georgia. Once he'd read the bill, he decided it needed to be killed.

"I thought it was just terrible, absolutely terrible," he said. "I believe it's not that complex. All this is for is to discriminate. If you're not going to discriminate, you don't need the darn thing."

The proposed law, Bowers said, would allow people "to use religion as an excuse for his or her interpretation of the law and to get out from under this, that, or the other law."

As a longtime state lawyer, however, Bowers got most exercised when describing what he felt is one of the biggest issues with the legislation: administration of the law. The religious liberty bills would put the onus of enforcement on regular people to adjudicate between what is fair and unfair, he argued.

"It's not so much what gets into court," he said, "it's what's happening on the front line of education or the front line for the policeman or for health care. It's just going to be a mess — and it's going to take a long, long time to unravel, if ever."

And though Bowers repeatedly stressed that he is "not trying to make some big, national statement," his past makes it hard to avoid doing so — a fact that he acknowledged likely was the reason why Georgia Equality approached him in the first place.

"I've got nothing to lose!" he shouted excitedly. "I'm 73. They can't send me to Iraq or Afghanistan. And I'm never going to run for office again. What the hell. I'm trying to tell it like it is."

Bowers' views were once very different.

In 1986, Bowers, then a Democrat, asked the Supreme Court to reverse an appeals court decision "holding that the sodomy statute violates the fundamental rights of homosexuals."

The Supreme Court took Bowers' case against Michael Hardwick, a gay man, leading to a decision that haunted cases over gay rights for decades.

Justice Byron White wrote the court's 5-4 opinion upholding Georgia's sodomy ban, calling the claim that the Constitution bars such laws, "at best, facetious." White called it "obvious" that prior court decisions asserting which fundamental rights are protected by the Constitution would not include "a fundamental right to homosexuals to engage in acts of consensual sodomy."

Asked about the distinction between his position today and his position then, Bowers registers that this clearly is an issue he's considered — both aware of the consequences of his actions and changes in his views since then, yet still of the belief that he was just doing his job in 1986.

"This is all I can tell you, I was trying to uphold the laws, which was my duty," he said. "They were the law, and I took an oath to uphold the law, and I did that. And the Supreme Court of the United States said that they were legitimate."

He is keenly aware that, for some, the memory of his actions in office will be strong.

"I will leave it to others to judge me, I'm not going to judge myself. For better or worse, that's for others to do," he said. Then, without prompting, he continued, "I never had an evil animus toward gay people. I never did. I worked with an awful lot of gay people in the attorney general's office, here in this law firm — but, that's for other people to judge."

Then, more: "Have I changed? Of course I've changed. I'm 30 years older, life changes all of us. We grow. That's the best I can tell you."

That was nearly 30 years ago. The justices themselves revisited the issue in Lawrence v. Texas 17 years later.

In the meantime, though, sodomy laws — and the constitutional permission slip provided for them by the Bowers decision — were used to justify a range of anti-gay treatment, from adoption laws to employment policies to security clearances.

Bowers, although he didn't go into specifics, does acknowledge that effect. "I realize all of it, of course," he said simply.

In 2003, though, the Supreme Court rejected and invalidated the ruling in the case that bears Bowers' name.

"The rationale of Bowers does not withstand careful analysis," Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote in the court's Lawrence opinion. His conclusion was direct and unambiguous: "Bowers was not correct when it was decided, and it is not correct today. It ought not to remain binding precedent. Bowers v. Hardwick should be and now is overruled."

So, which decision — Bowers or Lawrence — does Mike Bowers think is right?

"They both were right — for their time," Bowers said, unwilling to tear down his own career — but also acknowledging that others might.

"Should either one of them have been different? I'll leave that to the Supreme Court; I'm not going to second-guess the Supreme Court. That's done and over and passed. I mean, even our president has changed his view on gay marriage," he said. "But I'm not trying to justify myself — I will let other folks [judge me]."

But, Bowers — and his views — have changed.

"Part of that's getting older, having grandchildren," Bowers said, laughing. "I've probably mellowed a lot."

President Obama, in announcing his changed view on same-sex couples' marriage rights in 2012, mentioned his children's views on the issue as part of the reason why he was announcing his changed position. Asked if Bowers has had similar conversations with his grandchildren, he bristled.

"No. Hell no. I've got seven boys and one girl. They talk about baseball, hunting, ATVs, a couple of them ride horses with me. They're outdoorsmen and they're athletes; they don't talk about that. Good grief," he said. "I have a farm. They're outdoor people. They like to hunt. They don't talk about politics, good lord."

Although Bowers doesn't default to a common refrain among public officials who have changed their views about gay people — about children or grandchildren persuading them — he does acknowledge that change. And the change is real.

When asked about the Supreme Court's pending marriage cases, Bowers said nationwide marriage equality was "the most likely end-point," adding that if some states recognize the marriages as legal, ultimately the others will follow.

He went further when it comes to his own view of same-sex couples' right to marry, giving two answers.

His first answer was quick and painless: "I want people to be left alone." But then, he gave a second answer: "I genuinely believe that everybody, all people, need someone to love and be loved by. I truly believe that."

He went on. "I've been married to the same woman for almost 52 years. It has not been perfect, there's no question. And a lot of that's been very public," he said, referencing an affair Bowers had, which was revealed during his 1997 gubernatorial run. "But, we are still married. We still love each other very, very much. It is the most important thing in my life. We have survived. We'll be married 52 years the eighth day of June. And that is terribly, terribly important — for all of us — to have someone to love and be loved by."

"That's, I hope, why I am sensitive," he said, adding, "And, my faith says that the second most important commandant of my faith is to love your neighbor as yourself."

The man who represented Michael Hardwick before the Supreme Court, Harvard Law School professor Laurence Tribe, is taking in this week's developments with a similar gracious-but-not-ignoring-the-past approach to Bowers.

"I've been delighted to watch Mr. Bowers evolve," Tribe told BuzzFeed News. "Better late than never!"