Among some friends and colleagues there's a running joke that, when it comes to tech and crisis communications, there is one golden rule, a strategy so powerful and airtight that it can virtually ensure your company will weather the most harrowing scandals. I'm going to let you in on it now. First rule of tech PR: Never share anything. Ever.

There are some — most notably, Amazon — that observe the rule and worship at the church of radio silence. And, for the most part, it works quite well. Tech news cycles are as short as they come and, when it comes to technology, consumers have perfected the art of selective memory in favor of convenience.

The downside of secrecy, of course, is that you develop a reputation for secrecy. And so, in recent months, some of the tech giants have sought to defy the golden rule, to appear transparent, and to pull back the curtain a bit. What they've discovered is the catch-22 of tech PR right now: Consumers and the media love your product, and demand transparency — until they actually learn what's going on behind the scenes.

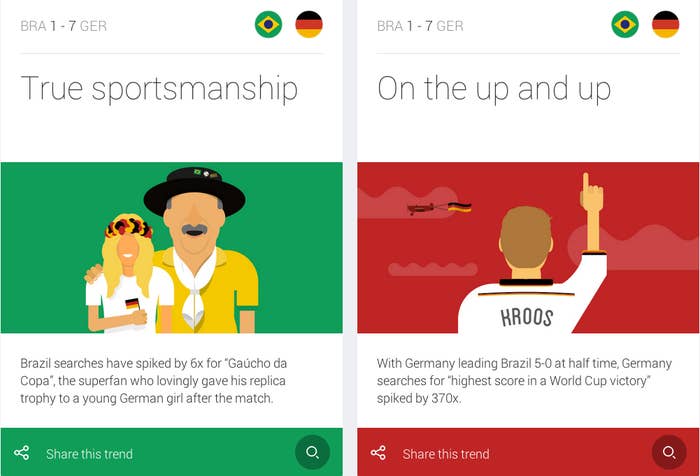

The most recent example comes this week in an NPR piece, which goes behind the scenes of Google's "experimental newsroom," which the company created for the World Cup in order to "turn popular search results into viral content."

Google, which has treated its algorithms as competitive secrets since it launched, no doubt saw the piece as an opportunity to highlight a new, fun trend-based initiative. Previously, Google Trends have been widely reported on and seen as a harmless way to harness and demonstrate the power of the company's data and algorithms. But the NPR piece took a different tone, opting instead to focus on Google using its proprietary data with a "clear editorial bias" and filtering out negative search queries to deliver information that people are more likely to share. From the piece:

After the dramatic defeat by Germany, the team also makes a revealing choice to not publish a single trend on Brazilian search terms. Copywriter Tessa Hewson says they're just too negative. "We might try and wait until we can do a slightly more upbeat trend."

It's enough to trigger an already-heightened sense of unease in tech and media spheres. On one side, media narratives have been known to sensationalize small, internal and experimental initiatives inside tech companies as indications of future strategy. And on the other, there's the search giant's seeming desire to curate its data to make news, which feels, if not a little bit shady, almost impossible to compete with. Google, big data's towering overlord, is entering the newsroom game! The world's most powerful information giant is filtering your news like everyone else! And doing so with readily admitted human bias!

This story on Google's news team jiggering with what emotions to cater to reminds me of the Facebook algorithm mess. http://t.co/gYQQO0hxx0

what's the algorithmic ideology of google's newsroom? what politics are supported or undermined when "negative" stories aren't disseminated?

For its part, a Google spokesperson offered up a statement on the subject of its World Cup trends, which was profiled in numerous other outlets before NPR:

Our social channels exist to share interesting and relevant information to the people who want to hear from us. Unlike your average 16-year-old, we don't share every single thing we might have to say. Throughout the World Cup, we've shared more than 150 tidbits in 13 languages looking at Leaping Legends to Waving the Flag and everything in between. If people want more, they can always use google.com/trends to see what topics are trending at that time. Our primary goal, more than anything else, is to share what matters most at that moment to the most people. And, it's good to have that goal, as we don't want to have to rely on penalty kicks.

The ethics/concerns/future implications for the news business aside, it's hard to understand why Google would let reporters in on these efforts, especially given the current media maelstrom surrounding big tech's use of algorithms, data, and the manipulation (of any kind) of emotions. Google has seemingly little to gain and everything to lose by reminding users that it has a team of data scientists and copywriters at the ready to turn your data into a neatly packaged, socially optimized product. With almost no provocation, Google opens itself up to this line of thinking:

The reality is that if it wanted to, Google could instantly become the most powerful newsroom in the world: http://t.co/CYr8VDvSHo

"I think here you're seeing the unhappy marriage that exists in large tech company public relations," PR firm founder and author Ed Zitron told BuzzFeed. "They see the cool hot young startups, who can let people behind closed doors and want a bit of that, but at the same time they need to be the big public, multibillion-dollar company can't say anything."

Zitron argues that, in these cases, size is often to blame. "The problem is they want to be both things. Theres' a maelstrom of different voices in a company Google's size. Somebody who wants to be cool and somebody who wants to be quiet. I don't envy them because god, that must be exhausting — the constant battle of how we need to be perceived. Do we need the startup-y look?"

Google is certainly not alone. Last year, in an attempt at transparency, Facebook introduced a series of blog posts geared toward explaining News Feed tweaks that seem to have had the opposite effect. For publishers, who depend increasingly on traffic from Facebook — and thus worry about a traffic-destroying algorithm correction — they're a source of anxiety and a reminder of the product's subjectivity. And for regular Facebook users, despite their lack of any real disclosure, the posts prompt their own small news cycles and invite new speculation about what makes News Feed tick. By pulling back the curtain part of the way, Facebook actually fueled some of the conspiracy theories it was trying to quash.

But, in many cases, big tech companies still want a piece of the news cycle. "In the NPR instance, Google could've said nothing and it would have been no problem at all but it also would've led to zero press, " Zitron said. "Ultimately, they wanted press because it's a cool story and I think there was a good chance the press would've been very sympathetic to it."

It's as good a sign as any of the growing disconnect between the increasingly powerful web giants and its users. For many, the uncertainties of an algorithmically run, data-driven future pose a potential threat to our very agency, or, at the very least, leave us slightly queasy. Google co-founder and CEO Larry Page sees it differently, as he noted in an interview with the New York Times' Farhad Manjoo:

For me, I'm so excited about the possibilities to improve things for people, my worry would be the opposite. We get so worried about these things that we don't get the benefits. I think that's what's happened in health care. We've decided, through regulation largely, that data is so locked up that it can't be used to benefit people very well.

Page concluded telling the Times he "would encourage people to have an open mind, and to look to the future with a sense of optimism" for the company's grand vision. Trust us.

It's not really a plea, but a suggestion. Google has made the potential rewards for that trust abundantly clear as part of it's public image strategy: The company will use your information to teach machines how to drive cars, keep your home the right temperature, and maybe even keep you alive longer. What's less clear though are the risks, which is what makes these behind-the-scenes peaks so unnerving. Like Facebook, Google's effort to open up doesn't present a window, but a two-way mirror. What little we see only reminds us of all that we can't see.

Story was updated to include a statement from a Google spokesperson.