Look out the window of Superintendent Greg Alexander’s office in Garden Valley, Idaho, and you’ll see the football field — where, if you wait patiently, you’ll also see one of the herds of elk that fill the valley, their winter antlers blurring with the mountains behind. Alexander has a video of them that he likes to show off, as he did one morning in January. The elk stream by for a solid minute before you hear Alexander’s deep, linebacker voice boom from behind the camera: “Yep, I work here.”

As the video ends, Alexander tells me to turn and look over my right shoulder. I see something that looks like a wall — the specifics of which he’s requested I not describe — but which he informs me is, in fact, a camouflaged safe. Inside that safe, there’s a rifle.

“That’s how close these safes are,” he says. “And it’s been sitting here this whole time we’ve been speaking. You didn’t notice. It’s simple, it’s locked, and I have the ability to get into it. Without electricity, I can still get into it. At Sandy Hook, they put millions of dollars into security, they had all that stuff to help make the school safer, and you just feel awful that it didn’t.”

"If I can’t take care of our kids by saying I’m going to call the police, then I’ve got to figure out a different way.”

Those safes are the reason that the Garden Valley School District, enrollment 235, has recently found itself in the national news. For the last year, select Garden Valley teachers and administrators have been training to handle rifles in safes placed in undisclosed locations (outside, in hallways, or in classrooms) across the school, which houses grades K through 12. Open and concealed carry is “permitted” in schools in some capacity by 18 states, but formalized programs remain rare. Garden Valley’s is one of very few that does not involve teachers actually carrying guns in the classroom.

There have been 169 school shootings in the three years since 26 were killed at Sandy Hook Elementary in 2012, and many see it as logical to work toward fewer guns in the classroom, not more. On the satirical site Wonkette, a representative comment declared: "'Rural Idaho student/teacher/administrator shot by student/teacher/administrator with official school gun’ watch starts now.”

But the specifics of Garden Valley’s situation — its isolation, its particular approach to training — shifts the debates that normally swirl around guns in schools, reframing them in terms of practicality. As a blogger in the Spokesman-Review averred, “This might be an exception to the rule re: how I feel about guns on campus.”

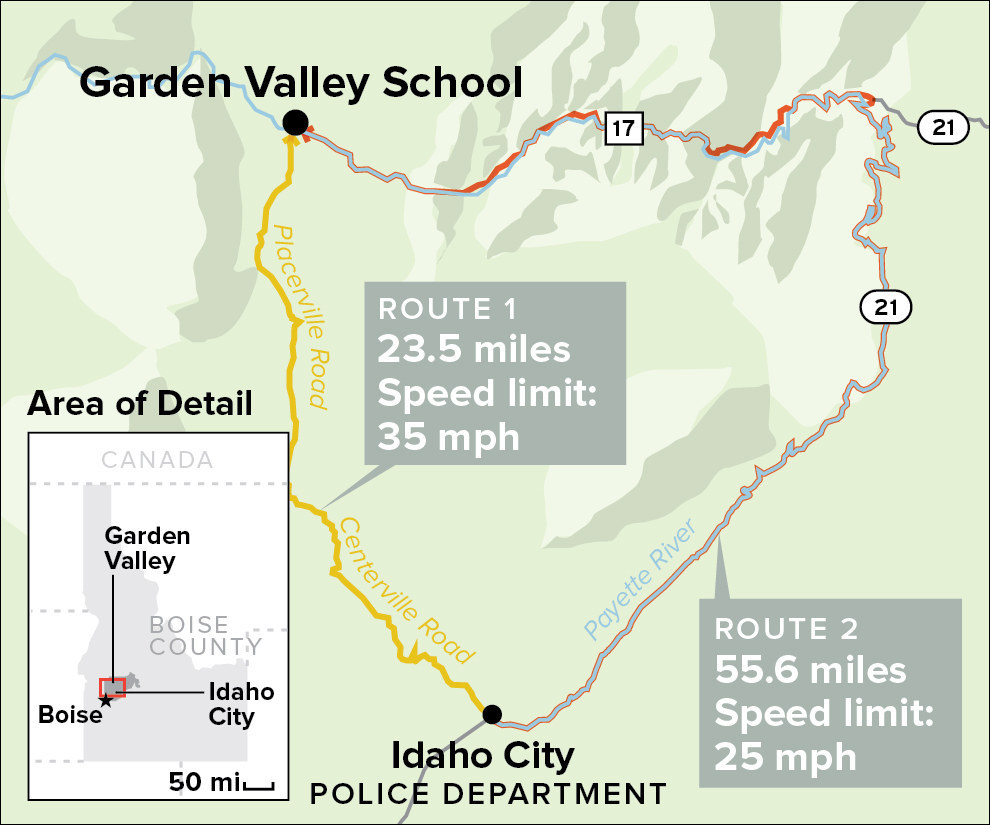

“On any given day, the police could be 45 minutes away,” Alexander told me. “And a gun situation could happen in between two and five minutes. So how are we going to deal with that? We want our kids to stay safe. So if I can’t take care of them by saying I’m going to call the police, then I’ve got to figure out a different way.”

Situated just over an hour away from Boise, Garden Valley couldn’t feel farther from the state’s urban center. Ten miles out of the city, the highways narrow to two lanes; the shadows from the mountains get deeper; passing opportunities become perilous and rare. Keep on Highway 55 and you’ll hit Boise County — which, confusingly, does not include the city of Boise — an area about the size of Delaware, with a total population just over 7,000. From there, the road hugs the Payette River until it forks in two, and Garden Valley unfurls in the space between.

“We have a geographically challenged county,” Janet Juroch, a reporter for the local paper, the Idaho World, told me. “From here to Idaho City, it’s over a dirt road! And it’s a good dirt road, but it’s an hour drive on a good day. You can’t go more than 25 miles an hour, and it just beats you to death.”

But Idaho City is the county seat — and the closest police station. Officers patrol through the area, but patrons at the local bar say they only really come around when they know there’s a theme night at the bar; after Ugly Sweater Night this past December, cop cars hovered around the entrance.

Idahoans have been fleeing the “big city” of Boise for the Garden Valley area for decades. There are thick, isolated woods in every direction, multiple natural hot springs, and golfing at Terrace Lakes, the Dirty Dancing–style development that, during the winter, hosts a game called “snolf”: hitting a tennis ball, in the snow, with an implement of the player’s choice.

Cell phone service in the valley is weak and at times nonexistent. As a result, no one, not even teens, walks around with their eyes glued to their phone. Because of the size of the school, Garden Valley plays eight-man football — a version of the sport, popular in small towns, in which defense is a low priority and the scores run high. Alexander’s biggest concern isn’t threats of violence, but absences: When a parent just can’t get their kid to school, either because of weather or a broken-down vehicle. “Some parents decide to live out in Primitive,” he told me. “It’s called Primitive — that tells you something right there. They have to plow their own stuff, do their own snowplowing. You have no idea how far up they are in those trees.”

In Idaho, where the state has continued to slash the budget and decrease taxes, districts rely heavily on bonds, or "levies," to fund new buildings and run the district on a year-to-year basis. These bonds must pass by a two-thirds supermajority, and in a district like Garden Valley — filled with snowbirds and residents who own massive swaths of land — it’s incredibly difficult to muscle one through the process. That started to change about ten years ago, when the valley’s so-called old-timers, whose family names can be found on the names of streams and buttes that crosshatch the county, became increasingly outnumbered by a mix of retirees (some from Idaho; most from California, a name that’s uttered like a dirty word), “new blood,” and telecommuters whose jobs allow them to relocate.

Surveying the political landscape, you can see how it took nine tries to pass the bond to fund a new school. But now that it’s completed, you can also see how the town rallies around it. On a Friday in late January, the bleachers of the school gym were filled for a home basketball game. The next day, the school would host the funeral of Orpha Ward, a woman who’d graduated from the high school in 1942 — and mother of Alan Ward, who serves as county commissioner, school board member, sawmiller, and, if you believe the blogs that cover the intricacies of local politics, one of the most controversial figures in the community. He’s also, according to those who know such things, the man responsible for the guns initiative.

Ward drives a massive flatbed Dodge Ram that, like every other vehicle in the county, bears splatters of gravel and dirt and slush. (The best way to tell an out-of-towner in these parts, people say, is by the cleanliness of their car.) He wears a plain chamois shirt and well-worn jeans; when he walks into Wild Bill’s — a coffee shop that doubles as the best place in town to find internet — half the customers say hello.

Ward speaks in a steady meter, his speech peppered with “well, now, you know.” When asked about the genesis of the guns program, his memory is imprecise. “I don’t know if it was after Newtown. All of them were just so awful,” he tells me over a cup of coffee that cost a buck. “But living in this community all my life, I felt some responsibility to try and make sure that couldn’t happen. Newtown was just unimaginable. They’re all unimaginable. But that one in particular, though...”

He pauses, blinks back tears. “I'll be honest with you. The gun program, I certainly pushed for it. Every month the school board would invite people in and talk about whether we should have concealed carry or a gun safe/storage deal. We talked about the composition of the building and what would be efficient and not too powerful, how far the sighting distances are. There’s just a horrific amount to it.”

“It was all very well-calculated,” he adds. “And coming from a board and a group of people who really cared. Not in any way off the cuff.”

After Sandy Hook, many schools began conversations about how to better protect their students. Nearly a year after the shooting, Garden Valley presented a plan to the Idaho State School Boards Association requesting a firearm training program, available to all school employees, through the state police academy. The proposal was voted down, but around that same time, Ward found himself delivering a load of firewood to Steven Ryan, who lives in the far western edge of the county. Ryan’s résumé includes 23 years on the police force and a term as a SWAT team commander; he currently trains police officers and members of the military across the U.S. on “active shooter” situations. “I sure’d want him on my side in a battle, I’ll tell you that,” Ward says. “That man can shoot.”

Ward asked Ryan, whose email signature is “The only thing that can stop a bad man with a gun is a good man with a gun,” for his thoughts on the issues facing Garden Valley, and Ryan prepared a presentation for the board — including a slide indicating the states with the lowest number of school shootings (at the top of the list: Idaho: 0 shootings; 0 dead).

“People think guns in schools and think handguns,” Ryan says. “But a handgun is really hard to shoot without hurting someone. So I talked them out of that. Instead, we went with a handgun-caliber rifle: a Beretta Storm 9 mm, which is very accurate, with very little felt recoil for the shooter.”

Students don’t know the location of the safes or who, exactly, has received training.

The board discussed the policy for several months before voting unanimously, in October 2014, to approve it. The next five months were spent refining the wording; acquiring the rifles (at least four, which were purchased, at $680 apiece, from a Boise gun store); installing safes, donated from a local machine shop; and scheduling training sessions. By May 2015, the safes, each of which is camouflaged in a different way, were in place. (Students don’t know the location of the safes or who, exactly, has received training, but as one resident told me, “I’ve been to the gun range, so I know who they are.”)

Soon after, the news went national. Like the signs that will soon be posted at the entrance to the school declaring it “armed,” the publicity was intended to announce, on no uncertain terms, that the school was ready to defend itself. “The fact that we’re prepared to respond so quickly is the real deterrent,” Ward told me. “Those who may do something know that they would be met with resistance.”

According to Ryan, “When we talk about making our schools safer for our children, we talk about target hardening. In an urban environment, you have ready access to resource officers and police, which means [an attacker] knows they only have so long until law enforcement responds. But when you get away from that urban environment, they think, I can do a lot of damage before cops get here. A lot of attackers intend to [commit] suicide, so they’ll analyze the situation and say, 'I’m gonna go someplace where they haven’t prepared.'"

“When you look at active threat situations,” Ryan says, “lives are measured in quarter seconds. Any quarter second lost is a life lost.”

Ryan came up with a specific plan for the teachers, each of whom goes through a vetting process, and trains three or four times a year. “I’m big on basics: first and foremost, how to safely use a gun. I teach them the tactics and techniques to be safe in a crowded, chaotic school environment. If they have to shoot the gun, they don’t want to miss — you don’t want to shoot the wrong person. So we work on marksmanship.”

For a recent training, teachers spent a full day working on scenarios using airsoft guns, which pelt the target with stinging air, and role-playing as “actual adversaries” to ramp up the stress quotient. “Nothing can compare to actually having someone shoot at you,” Ryan says. “But you want to put them under similar stress so they can learn to respond.” Representatives from the sheriff’s office also attend the trainings, in part to avoid a scenario in which law enforcement arrives and cannot distinguish between the “good guy with the gun” and an armed shooter.

“Steve has such a gentle approach,” Ward told me, noting that Ryan is paid only for his travel expenses. “He doesn’t have to do this. He does it out of the goodness of his heart, and he’ll tell you it’s for the community.”

From the next table over, a seventysomething man in coveralls turns, stands up, and shakes Ward’s hand. “Looks like you’re surviving that job,” he says, referring to Ward’s relatively new post as county commissioner. “I couldn’t handle it, I tell you,” he continues. “I’d wanna kill somebody!”

“When you look at active threat situations, lives are measured in quarter seconds. Any quarter second lost is a life lost.”

“Well, you can’t do that,” Ward chuckles.

Ward drives the quick seven minutes over to the school, which is set back from the main road by a quarter-mile entrance road. White buses marked FIRE PATROL are parked like matchsticks in an enclosed lot. Like so many areas in the Northwest, the area’s been hit hard by wildfire; five years ago, a blaze devoured the hillside when someone at the skinny-dipper hot springs tried to set her toilet paper on fire so as to “leave no trace.”

The school is shaped like a massive plus sign. On one side, the artwork of elementary school students and Khan Academy achievement certificates line the walls. On the other end of the hallway, three chimes indicate a class change, and middle and high school kids yell and push and flirt as they move through the single hallway. For budget reasons, classes run just four days a week. Fifty-eight percent of the students in Garden Valley are on free or reduced-cost lunches — 10% higher than the state average for Idaho. Alexander describes the school as “a very white community”; according to census data, the county is 95.4% caucasian.

Above the blue lockers that line the walls, there are composites of every graduating class going back to 1930. Ward searches for his mother’s name but doesn’t take the time to find his. He graduated, but barely: “I never was too good at school.” We reach the end of the hallway, and Ward leans in, speaking in a hushed tone so as not to disturb a group of elementary students circled around a teacher 10 feet away. “You see here, how you can see all the way from this end to the other? It’s a straight shot. That’s why we’ve got rifles.”

Greg Alexander fills the doorway to his office the way all men who’ve spent time as a vice principal — a job known for its role in enforcement — seem to do. He’s built like a football player, which he was, back in early ’90s, for Boise State. He says hello with a big, meaty handshake and wears a purple oxford with yellow embroidery: Garden Valley colors. A hodgepodge of memorabilia overflows his walls: There’s a plaque engraved with “We Love You Mr. A”; just below, the "Footprints" Prayer is mounted on wood. “That’s just where I’m coming from,” he’d tell me later in the conversation. “I just asked the Lord if this was the place I needed to be.”

Since graduating with a degree in secondary education in 1993, Alexander has taught at a middle school, a high school, and a private Christian school in Boise. He worked as an administrator in Caldwell, a suburb of Boise whose high schools deal regularly with gang activity, but here in Garden Valley, discipline issues generally range from gum chewing to online bullying — although, before Alexander’s tenure, a student did bring a knife to school. The police were called, according to the superintendent at the time, but they did not arrive until the next day.

Alexander’s only been in his job six months, but Garden Valley suits him and his family. Instead of staying in Boise to complete her senior year, his youngest daughter opted to transfer schools, and his wife’s dabbling in local real estate. “The other day, she was way out there to look at a property,” he tells me, “and she talked to one of the worst meth dudes up there. But she had no idea. He was all helpful, giving her directions, and I’m like, ‘Honey, why don’t you call me when you go places like that?’ Jeez, I’m gonna have to get her a concealed weapon.”

Six months after the guns policy was approved by the board, Garden Valley received a grant for a restorative justice officer, or RJO — an armed member of the police — who comes up from Idaho City and spends two days a week at the school. RJOs and school resource officers (SROs) are most schools’ primary means of defense against the threat of an active shooter, and with the expansion of RJO/SRO programs across the nation, school death rates have fallen. Yet many districts, especially rural ones, have struggled to find continuous funding for their programs, which rely on a mix of state and national grants and county budget dollars. Currently, Garden Valley shares its RJO officer with Horseshoe Bend, and the grants that fund him could disappear at any time.

Alexander never hunted growing up. Unlike many kids who grow up in Idaho, he hadn’t even taken hunter’s safety. That changed earlier this year. “I was pretty much the oldest in there with a bunch of fifth-graders,” he explains, laughing. “And there were other kids in there who were taking it for the second or third time because they like it. These kids, they keep going over this stuff: Ammunition goes over there; you put the guns in the safe at home here, or in the rack there. They have respect for the weapon.”

“My students back in Caldwell didn’t get a lick of that,” Alexander adds. “All they know is, ‘Here’s a gun — dad’s drunk, passed out — and here’s this gun; let’s look at this thing.' And next thing you know, one of them’s dead.” By contrast, guns in Garden Valley are something like a way of life. Rob Harold, who owns the Two Rivers Grill in the center of Crouch, explained it this way: “I grew up in Portland, and even eight years ago, I would’ve been against it. But the mountains have grown into me. Look at where we are! And those kids — those kids are the most valuable and vulnerable thing we have.”

The lunch bell rings and Alexander hustles down the hall to grab his plate: nachos, piled high with black olives, with a side of canned corn. I’m left in the care of the school administrative assistant, who moved to Garden Valley for high school; her husband has lived here all his life. They have two elementary-age boys, both of whom attend the school.

“My dad is the fire chief here, and a lot of us have scanners, because during the wildfire season, you have to be listening,” she says. “If anyone heard that there was some sort of emergency going on here, I think we’d have serious problems.” Parents would come, with their own guns, to the school. “And you wouldn’t blame them. The program is a good solution for something that we felt was out of our control.”

“I can see how other communities wouldn’t be as receptive. But that’s just our normal.”

Alexander had mentioned something similar when describing the parental reaction to the policy. “The local television station came up and couldn’t find anyone that was against it. What they found was, If they didn’t take care of it, we would. And that makes me even more nervous. It confirmed that we need to make sure the parents know we have things under control.”

Down the hallway, Laree Jones is supervising lunch. She’s worked at the school for years, both as a teacher’s aide and coaching every sport save football. A teen girl comes up to ask about the price of the winter dance — "it's $3 for a single, $5 for a couple, and it can be any couple — you can come with your brother, we don’t discriminate.” Before the dance, the students come to the gym to decorate and have informal lessons in western swing. As for the guns policy, “I can see how other communities wouldn’t be as receptive,” Jones says. “But remember there’s pickups all over the place with rifles on the gun rack. That’s just our normal.”

Out the window, an elementary school kid is running around in the newly fallen snow with a hammer. “He must’ve brought that for his tunneling,” she mutters, before another teacher grabs it and the chimes usher the rest of the class inside.

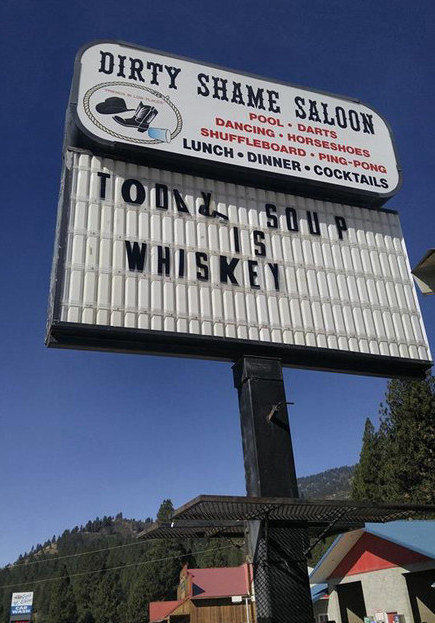

Everyone in town refers to the local bar, The Dirty Shame, as “The Shame.” As in: “Will I see you at The Shame tonight?” It has the curious effect of making people sound like they’re meeting for drinks deep inside an emotion. In the mornings, a bunch of old-timers come together, in one waitress’s description, “to mostly just sit there and bullshit. Heavy on the bullshit.”

An easy-smiling mother of four named Holly manages the bar and keeps the peace. There are microbrews on tap, but they’re mostly for the summer tourist crowd. During the winter, the locals go for mixed drinks or Coors, which many patrons retrieve by walking behind the bar, opening the fridge, and popping off the caps themselves, yelling, “One more for me, Holly!”

Earlier in the week, I was told that to truly understand the town, I needed to go to one of The Shame’s “Dirty Thirties,” which are really just rowdy birthday parties with a theme — in this case, disco. Starting at about 5 p.m., the bar is awash in the light of spinning disco balls and ample amounts of fringe and polyester. The guest of honor is a hotshot firefighter — the most elite, and dangerous, of the firefighting services — and in posters advertising the event, her face is covered in ash, overwhelmed with a smile.

The ages of attendees at the bar starts around 20 and ends over 70. Ward is here, stubbornly without disco wear, hunched with the old-timers at the bar. Iron welders and game guides and retired school board members are here, as is a local hunting guide named Darl Allred, who, earlier in the day, had taken me on a sleigh ride to feed the elk. Then, he was wearing a cowboy hat and a massive duster to keep off the snow; now, he has on a pair of leather hot pants and a shirt that sparkles.

Between refills of cabernet, Holly tells a long, involved story of a man who came into the bar, got angry when she cut him off, and pulled a gun. Eventually, she called the police, but the man resisted arrest, punching a cop in the face. “So the biggest guy on the porch runs over and jumps on the guy’s face,” Holly says. “And come to find out, he had another weapon on him, strapped to his ankle.”

Everyone does, as the cliché goes, know everyone, but they don’t necessarily like one another. “There are grudges in this county that run deep,” Alexander had told me earlier that day, a point elaborated by a woman who comes to the bar to stash her pool winnings, points to a guy sitting in a booth, and tells me, “His mother, she hated me and my husband, because we were kayakers, and they were loggers.” There are grudges between those who’ve worked to protect the gray wolf population and those who’ve seen the elk numbers — and the hunting dollars that accompany them — dwindle as a result, and grudges with roots in the school board and county commissioners’ office, both of which were wracked with small scandals, mostly around money-handling practices, over the last five years.

And yet there’s remarkably little dissent when it comes to the gun program — at least in public. The day before, at the lunch spot wedged in the corner of the mercantile, or “merc,” as it’s known in the valley, Heather Sipple had told me, “It’s kind of a normal idea and option for everyone here. I know it’s not like that other places. They automatically think, Guns, schools, terror, murder, horrible. But for us around here, I think it was like, ‘Oh, about time.’”

Anna Ross came in to check on the clothes she sells in another corner of the merc, chatting with Heather about their plans for the weekend, and which Ross Dress for Less they prefer when they make the trip into Boise. At the beginning of the school year, she posted a news items about the school’s gun policy on Facebook. “In the caption I wrote, ‘And this is where I live, and I know my kids are safe, so just save your comments for someone else.”

There are those in town who think it’s “a horrible idea,” but none of them want their name associated with that position on record. “I wanted them to do something with tasers,” one woman told me. “And everyone knew that there’s a teacher there who used to be in the military and that he always had a gun. He always had access to a weapon, but people just didn’t talk about it. So why did Alan [Ward] have to publicize this new weapons policy? In my opinion it’s because he’s trying to run for legislature. That’s it.” (Ward, for his part, won’t rule out a legislature run.)

“I’m dead set against it,” another woman told me. “But don’t quote me around here saying that. I think it was probably prompted by a few, and the rest just went along. And as for what motivated people, well, people who have guns don’t have to make sense.”

In a small building in the center of town heated only by a wood fire, Terry Lloyd is broadcasting from 98.5 KXGV, Boise County’s first and only radio station. The station plays a mix determined by their volunteer DJs — crooners, old-time radio shows, jazz, or, as Lloyd was playing when I arrived, classic rock. During our conversation, “Age of Aquarius” faded into Joe Cocker’s “Feelin’ Alright,” with Lloyd periodically breaking in with public service announcements, like a friendly reminder for listeners to call the gas company before they dig.

“I’ve been looking for a town like this all my life,” Lloyd, who has long blonde hair, a winter tan, and a radio voice an octave lower than her speaking one, told me. “It doesn’t get any more local than here,” she says. “We can do traffic reports that are like, ‘Well, three pigs runnin’ down the road!' That really did happen one day, I’m not making it up.”

To stay neutral in Garden Valley, Lloyd explains, requires a certain amount of lip-buttoning. “I think what happens here is that the relationships you make with people supersede whatever the political persuasion might be. Some people love to Obama bash. You just kinda learn to zip your lip — or you pitch them some shit and hope they’ll shut up,” she says.

As for the guns issue, she tries to look at both sides. “Our sheriff, he has to serve the entire county, and it would take him forever to respond to a problem here. But then you’re putting that responsibility on teachers!” She pauses, queues up the next song. “I don’t like to be wishy-washy on certain things, but you know, I don’t believe in guns, I definitely don’t, I’m against guns on campuses and that sort of thing. But I have a gun, in case I need it for wildlife or whatever, even if I don’t know where it is half the time.”

She leans back her chair, puts her hands behind her head, and smiles. “It’s kinda weird being a peacenik here, isn’t it?”

Earlier this year, Alexander and Ward traveled to the Idaho State School Board meeting in Coeur d’Alene, where they presented their program to a standing-room-only crowd. Afterwards, other Idaho districts have tried to implement similar programs. But none have passed. Two years ago, when a school board member from the Lake Pend Oreille school district, up near the Canadian border, submitted a proposal to arm teachers, community members launched an effort to recall him.

After Sandy Hook, the National Rifle Association (NRA) and National Education Association (NEA) diverged sharply in their recommendations for how schools should protect students. Launched in April 2013, the NRA’s “National School Shield” program, includes risk assessment, guidance on best practices, and an unequivocal call to increase the number of trained and armed personnel, including teachers and SROs.

By contrast, the NEA’s proposal focuses on a “dramatic expansion” of mental health services, pointed anti-bullying efforts, and increased gun control the form of background checks and bans on assault weapons and high-capacity magazines; a poll of its membership, conducted in January 2013, found that 68% opposed arming school employees. According to NEA President Dennis Van Roekel, “Guns have no place in our schools, period.”

“This is not an argument about gun control,” Ken Trump, president of National School Safety and Security Service, told me. “It’s an argument and an issue about best practices in public safety. Certainly many rural schools have a valid concern when response time is long, but put your money where your concerns are, and invest in a trained professional, certified police officer.”

“There’s a difference between protecting yourself versus asking those in law enforcement individuals to perform a law enforcement function,” Trump adds, “and no matter how you look at it, that’s what they’re doing. They’re asking educators and support staff to perform a police function.” As for budget concerns, he’s unsympathetic. "I hear that all the time, whether it’s in a large school or a small district. But here’s the thing: Your bottom line, not your rhetoric, reflects your priorities.”

“It’s kinda weird being a peacenik here, isn’t it?”

Still, every year, a handful of school districts across the country consider arming their educators. And for many, what hinders their efforts isn’t community opposition, but insurability. In 2012, insurance companies in Kansas and Indiana informed districts that any schools where teachers carried guns would be declined coverage; in Oregon, the school board association has implemented a policy in which each school must pay a $2,500 premium per staff member who carries a weapon. For districts already struggling with dwindling budgets, the premium is untenable.

Garden Valley’s weapons policy was approved by its Boise-based insurance company, and the board has assembled a plan to deal with the psychological and legal after-effects of an active shooter situation. “Not everyone has thought of that,” Alexander told me. “It’s going to be a difficult thing for that teacher to have to deal with that, if he shoots someone. We feel like that’s part of the cost, part of the liability, and we accept that.”

The district has also worked to flesh out other components of school safety: Teachers have been trained to deal with conflicts and on- and offline bullying, orchestrating “circles” that focus on dirt communication and taking individual responsibility. And while Garden Valley is too small for a full-time counselor, it’s working to implement a program that accepts Medicare and allows students to video-conference with mental health professionals via Skype.

But those initiatives still don’t address the question of isolation. Both Ward and Alexander acknowledge that the weapons program might not be suitable for every district. But it does, they say, make sense for theirs.

“Even though it makes some liberals nervous, it’s like our trainers say: Now we’re a hard target,” Alexander explained. “People that want to do damage, they don’t want to walk through the door and be stopped immediately and put down. I mean, there are parts of that scenario that I don’t like. And when you think about it too long, the idea of a gun in a school, sure, it’s awful. But still.”

It’s been open for only six years, but the Garden Valley gym already smells like decades of teenage sweat and squeaking rubber and boiled hot dogs. As the sun disappears behind the mountains on Friday night, the boys basketball team loses by 11, but the players still line up with the rest of the high school class to form a tunnel for the girls team to run through, their warm-up music blasting through the gym. Afterward, they retreat to the quarter of the bleachers they’ve taken as the student section, boys slouching on girls, girls slouching on boys, all carefully avoiding their family members positioned at various distances throughout the gym.

A man in the stands keeps yelling, “Justice! JUSTICE!” — which is confusing until it becomes clear he’s yelling at his daughter. “Justice, I know you can hear me — the whole gym can hear me,” he says, before handing her a buck and asking for some popcorn. The girls team has massive, swinging shorts; their warm-ups are embroidered with “As One.” The opponent is Salmon River, whose mascot is the Savage.

A cluster of girls with glitter in their hair and eyelids explain that no one even thinks about the guns in schools. “It’s just not a big deal,” one of them says, before the booming voice of the announcer calls for everyone’s attention. It’s Senior Night, and the parents of the seniors on the team gather at the center of the court, their arms overflowing with balloons and bouquets of flowers. Something sticks out from one of the dad’s hips, but it’s impossible to tell if it’s a gun or a cell phone or a Leatherman.

Later that evening, the students will head to the locker room and change into their dresses and Dockers and wobbly heels, and they’ll western swing under decorations they hung themselves. Down the hallway, an undisclosed number of rifles rest in an undisclosed number of camouflaged safes. Dotted throughout the valley, population density four people per square mile, there are a handful of men and women trained to use them.

And I’m reminded of something a woman, late in her seventies, spry and thoughtful and retired in the valley after many decades as an educator in Korea, told me earlier in the week. “It seems to me,” she said, pausing to choose her words carefully, “that people know virtually nothing about Idaho.”