A year ago, a friend of mine, a journalist, asked me if I could write a piece about my father — what memories I have and that sort of thing. When I think about it now, I think maybe he wasn't asking me to write about my father, but really about his death.

Writing about his life is more important for me. Because I will remember his death forever. But being able to remind myself of his life is becoming harder and harder. Memories fade much faster than you expect; that's why writing this is urgent and necessary for me. Maybe that sounds a bit dramatic. Sometimes I think I get that from my father. He used to perform theater in his spare time.

My father was born in 1957. He was the eldest of seven children. He was raised by my grandmother, because his younger brother, Ngabo, was born shortly after he was and his parents couldn't take care of two small children. After Ngabo, his parents and my grandparents had Ida, Olive, Mudeli, Mutesi, and Cyemayire. From this family of nine, only my Aunt Ida survived. The rest were killed in the genocide exactly 21 years ago.

The genocide in Rwanda began on April 6, 1994. Within 100 days, nearly 1 million Tutsis along with moderate Hutus were killed by Hutu militias. No family in Rwanda was left untouched by the genocide. Families like mine were torn apart. I grew up without a father, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins. The children of Hutu militias grow up without parents because theirs are in prison. And all that time the world watched idly and intervened not at all or not enough. Best known is the failed blue-helmet mission as well as France's involvement in the genocide.

But back to my father. He was the oldest and took responsibility for his family. He was the best in school and an overall great kid. After the sixth and last grade of primary school he was supposed to go to high school like other kids. He was not allowed to. Why? Because he was Tutsi. He couldn't continue with school because he belonged to an ethnic minority in Rwanda. He didn't let this obvious injustice discourage him: He repeated the sixth grade four times in a row until he was finally allowed to go to secondary school. Four times!

After secondary school he was granted a scholarship to study in Belgium. My mother, who is also Tutsi, received one too. They were childhood friends. I recently asked my mother when they actually started dating; she said when they were 15. For them, dating meant enduring this injustice together, swapping books and telling each other stories of different times.

Sometimes they held hands.

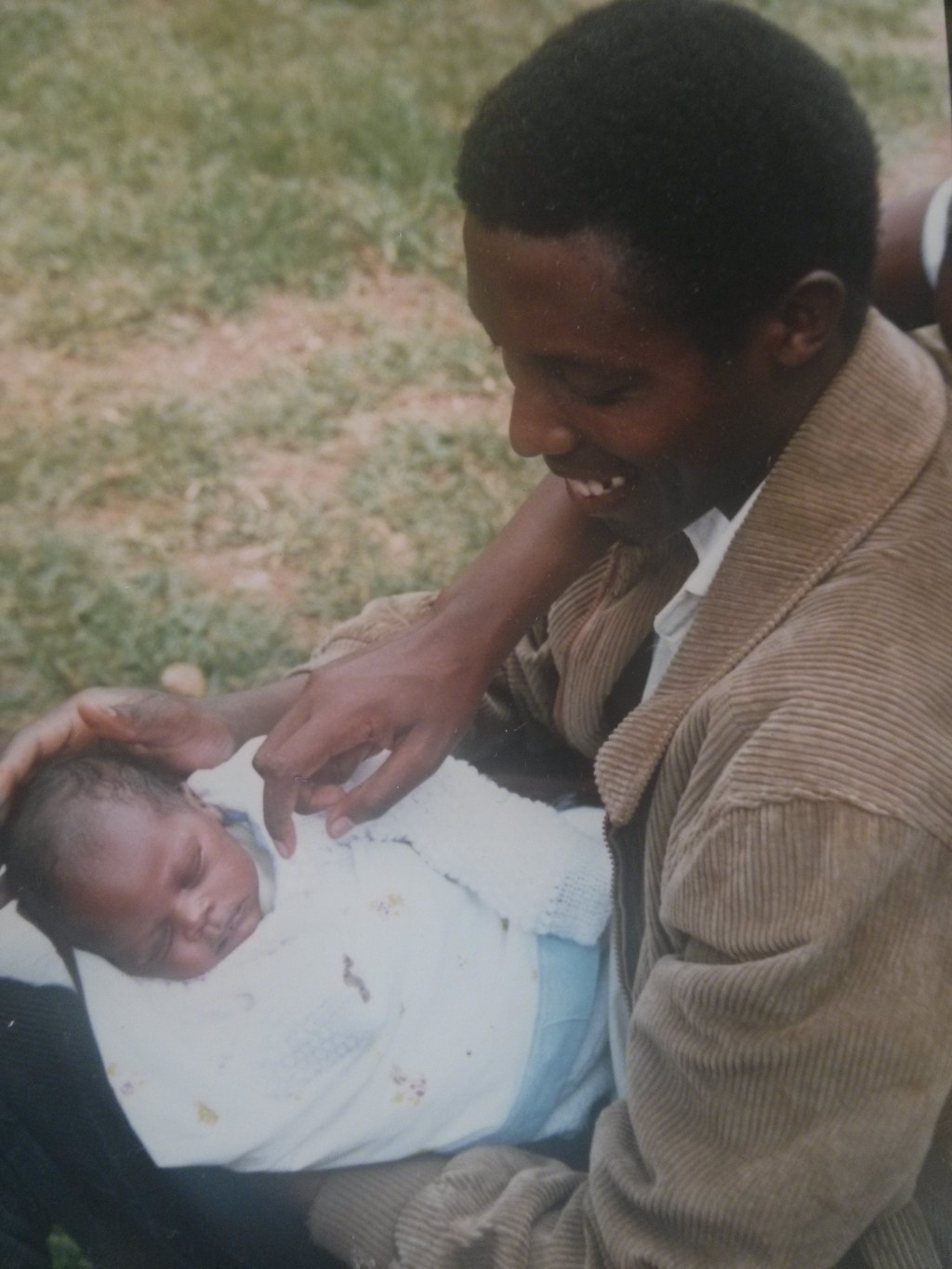

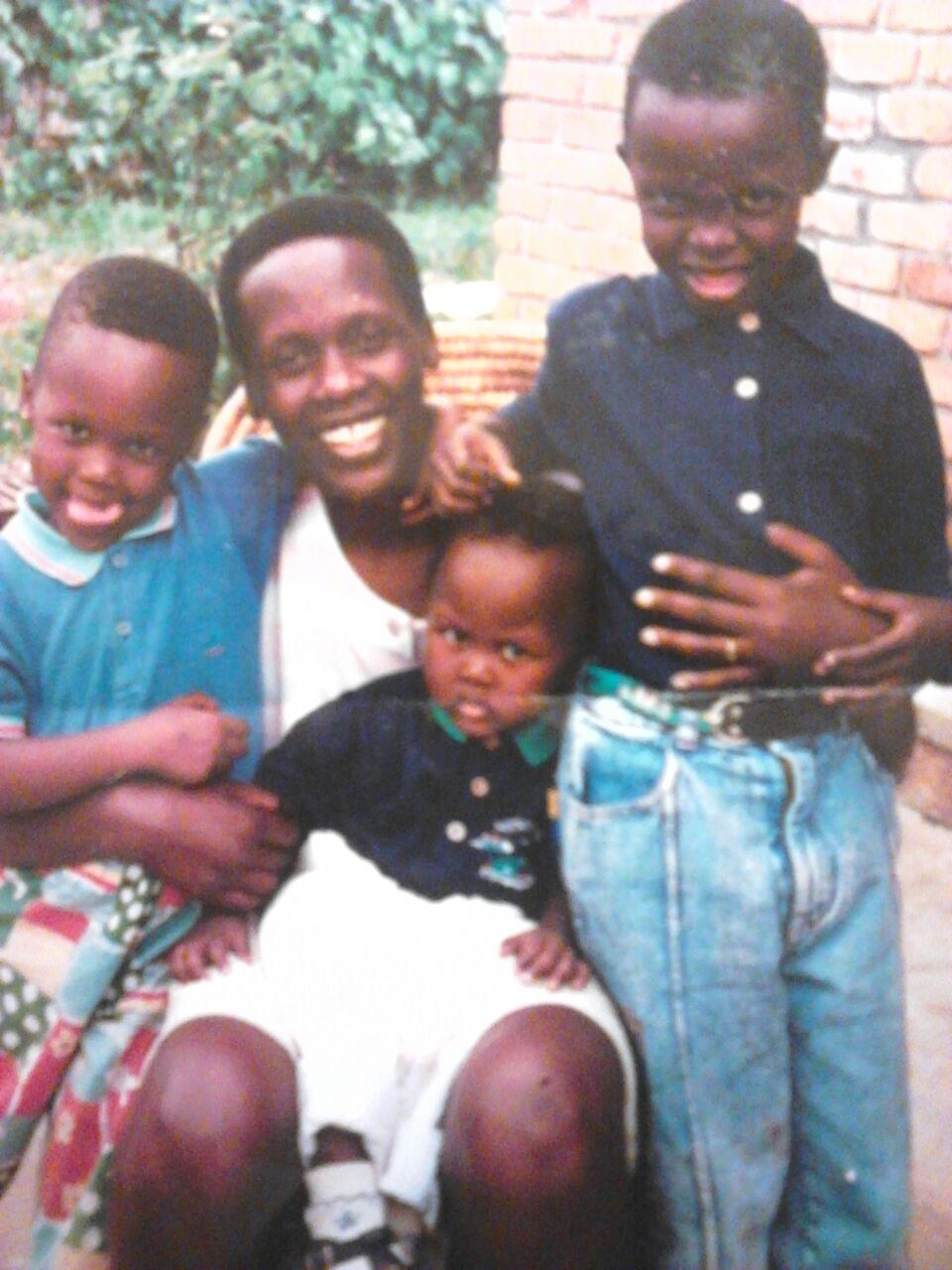

My parents returned to Rwanda in 1987 and married. My father was a teacher of French and sports as well as a prefect, a sort of co-principal, at a secondary school in our neighborhood. My mother worked for Oxfam in Kigali. They were in love, optimistic, successful, and pregnant. On an October afternoon in 1988, Canon Yaoundé, a soccer team from Cameroon, was playing against the Rwandan team Rayon Sport. My uncle Edouard wanted to pick up my father to go watch the game together right as my mother's contractions begin. My parents drove to the hospital, and a little bit later I was there. We still joke it was the only day I was ever on time.

Like any Rwandan family, we lived with extended family members. My father's sisters Mutesi and Mudeli stayed with us. They went to school in Kigali, the capital city. Mutesi attended the secondary school École Technique Officielle in the Kicukiro neighborhood. During the genocide thousands of Tutsis looking to hide were killed there.

On April 30, 21 years ago, we hid with our Tutsi neighbors in the school where my father taught. On that evening armed militias stormed our hideout, taking the men with them and leaving behind the women and children. After my father's death we hid in the Hotel des Milles Collines, now famous as Hotel Rwanda. I was 5 years old.

The Hutu militias killed my father and left him bleeding in the street. I pass the street often when I am in Kigali. Twenty-one years is a long time. A lot has happened in my life that he wasn't around to see. To this day I look at fathers with children and each time feel a mixture of envy and sadness.

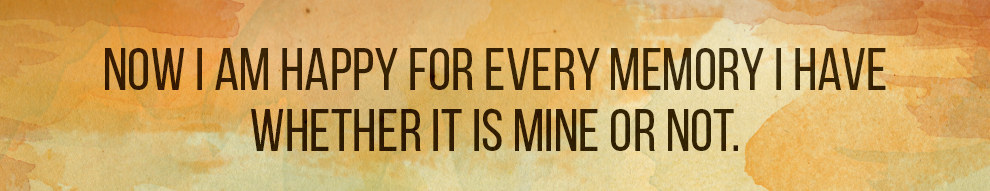

I had five years with my father. Five years is not a long time, but I cherish them. I sometimes tell my friends about my father. How he played basketball or how he rode through Kigali on a blue bicycle. I mix the memories I still have with what others tell me about him. That used to bother me. Now I am happy for every memory I have whether it is mine or not.

A year ago a college friend of my dad's sent us a recording of my father giving a presentation. My sisters and I sat together and listened to it. For a moment you could hear my father's voice in my kitchen in Berlin. I will never forget that. As my father slowly realized that he would most likely die, he sent a letter to his friends abroad. He asked them to look after us should we survive. Every time I think about that letter, I tear up. To imagine what he felt in the moment is too much.

As a child, for the first three years after his death I strongly believed he would come back. It was my biggest wish. For a while I even believed that my father came back disguised as our dog Tissy. Whenever I was in a plane and saw clouds I would wave every time and say, "Bye, Papa." And whenever I wrote in my diary I would imagine that he would read it. As if I were writing him letters. I always wrote to him about how tall I was and what grade I was in.

Every time I feel sad and miss my father I think of the countless orphans and widows that this genocide created. I think about those who to this day live under the worst conditions and on top of that grief, have to worry about how they will feed their families. I know that I have a lot to be thankful for. I am thankful that my mother and sisters survived with me, and that we have each other and can lead a life. Sometimes that keeps me from being able to properly mourn, and I don't allow myself to be truly sad.

But today I want to allow it. I want to bitterly miss him and to cry. I want to remember him and look at his pictures. I don't want to forget my beloved father, Innocent Seminega.

In December 2013 at a reading in Kigali, I noticed a woman staring at me for a long time. She approached me, with tears in her eyes, and told me that I reminded her of my father. As a young woman she had taken his theater class. He was a good dancer, told great stories, and gave good hugs. I get that from him. With other things I am not so sure.

For a very long time, I tried to keep my father alive. When I was 18 I had his name tattooed on my wrist. Most people who see it think it is a stamp from a club. Something that means so much to me doesn't mean anything to other people. I think that is exactly what all people struggle with that have lost a loved one — that the world doesn't stop, that it isn't important, or that no one really notices. I wanted the world to stop on the day my father died, but it didn't.

This post was translated from German by Ian Bateson.