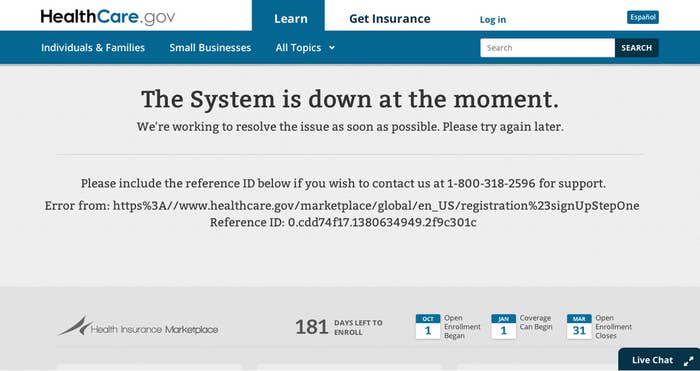

Once upon a time, Senator Harry Truman held the feet of wartime contractors to the fire, charging them of profiteering from producing the "arsenal of democracy" during World War II in hearings broadcast to the nation. Today, the scandal is not a warship that isn't seaworthy, a plane that doesn't fly, or rotten food. It's a website, Healthcare.gov, that has not delivered on its mission of enabling millions of Americans to browse and enroll in health insurance plans.

The debacle is merely the most visible example of how $80 billion spent annually by the federal government on information technology falls far short of delivering the quality or service any private company would expect at a fraction of that cost.

And while this is the first time many Americans have become aware of the issues that pervade federal IT architecture, it's hardly the first time that a federal government IT project has run far over cost and then not worked particularly well. In the wake of the botched launch, opponents of the Affordable Care Act are blaming the federal government itself, suggesting that this just simply shows the government cannot deliver on a project. But they would be wrong to do so.

At the heart of the federal IT crisis is a complex system of regulations that rewards contractors that are better at bidding on giant federal contracts than at building software. While the political figures who commission or oversee those contractors are ultimately culpable, the work itself is done by the private sector. That's not only true of civilian agencies, as the world was reminded when a private contractor for the National Security Agency, Edward Snowden, leaked key documents from the government and gave then to the press.

In fact, over the past several decades, more and more core information technology functions have been delivered by private contractors, not in-house staff. While a few government executives look for different approaches, private contracting is now the norm when it comes to how government IT is proposed bought, built, and maintained.

Given how well the Obama campaign used technology to support getting the Democratic nominee for president elected, I've seen many people wondering how his administration has so badly botched the technology behind his signature legislative achievement. To understand why this shouldn't be surprising, you have to know how different the ways campaigns and government agencies can buy and build tech are, as I said on Washington Post TV this past week, apples and oranges.

The short answer is that even presidential campaigns have a great deal of freedom to hire (and fire) who they want and take risks with adopting new technologies, from social media to data mining to mobile applications. Government agencies, by contrast, are bound both by regulations and culture. Many people I've spoken to in Washington over the past four years, in fact, have concluded that federal government procurement — how any administration can buy and build technology —- is broken. As former Presidential Innovation Fellow Clay Johnson observed this week, the Healthcare.gov fiasco "is instructive in that it highlights every piece of our procurement process that's broken."

Campaigns, by contrast, have much more control over how they buy tech, how they maintain tech, and how they build tech. That's not to say that all them do it well — BuzzFeed readers no doubt recall what happened to the Romney campaign and Project Orca — but it does mean that if there is great political leadership at the top of the campaign and they hire great chief technology staff who manage projects well, they have much greater flexibility to hire fire by an otherwise customized technologies the campaigns needs much more quickly.

This was abundantly true in 2008 when the Obama campaign used text messaging, email, and a website that will enable people to simply organize themselves to fundraise and sustain grassroots organizing. It was perhaps even more so in 2012 when, as Alexis Madrigal documented in The Atlantic, Harper Reed built an unprecedented technology operation that created the capacity for data mining, personalization and the creation of infrastructure for the campaign to build upon.

Federal agencies and, to be fair, state and local governments, have a much more difficult time buying and using technology. Why? Read the terrific Ars Technica article by Sean Gallagher in which he explains why government IT fails so hard and so often.

Why US government IT fails so hard, so often http://t.co/1arPAvumj1 old tech, dependence on outside talent, and contract madness.

Sean Gallagher

@thepacketrat

Why US government IT fails so hard, so often http://t.co/1arPAvumj1 old tech, dependence on outside talent, and contract madness.

First, there are huge numbers of regulations and rules about how technology can be bought. They're there for good reason, given decades or even centuries of private contractors providing goods and services, from profiteering in the Revolutionary War or Civil War when sold substandard food, uniforms, or ammunition to armies, or more recently when companies manufactured supplies and goods during the United States' many wars. There are decades of examples of fraud, corruption, incompetence, malfeasance, or other issues with huge information technology projects that have cost too much, gone on too long, and delivered substandard projects. There are good reasons for having many tough rules on how technology can be bought, in other words. The trouble is that all those rules are selecting for huge companies that are very good at getting contracts not necessarily in delivering results. They're also giving chief information officers and procurement officers an incentive to avoid the risk of working with newer firms, as opposed to managing it.

It's also no secret that many of the same companies have lobbying operations that may influence how regulations and legislation are constructed in ways that favor their interests or specific capabilities.

This is hardly limited to information technology, if you look at how contracts for a myriad of other kinds of goods or services are delivered to government, but IT now holds a special place in the hearts, minds, and hands of Americans, given how deeply integrated into modern society technology has become. To improve the situation, reform of how government is able to buy the best tech and recruit, hire, and retain talent is going to be needed. It's not clear if the political will to capacity exists to do so within this Congress.

It's not clear how much President Obama knew about the issues with this particular project, or how much his former CIO, Vivek Kundra, told him regarding the extent to which federal IT would hobble such efforts, though he has publicly expressed surprise at how dated the technology in the White House itself was when he came into office. The current U.S. CIO, Steven VanRoekel, does understand the issue and is taking the steps he can behind the scenes to improve on it in the national Digital Government Strategy, as is U.S. chief technology officer Todd Park. Both men, however, are up against the same beast of bureaucracy that has held back reconciling claims for veterans.

The uncomfortable truth may be that the White House and appointed officials simply don't have the power to enact immediate change in immense institutions. Despite the clout of the Office of Management and Budget, the primary lever the U.S. has wielded has been to cancel IT projects, not make sure they're built or acquired better — unless the agency CIOs work with them.

Could President Obama have changed the system in time to make a difference for Healthcare.gov? Maybe — but it's worth noting that federal IT procurement reform was just way, way low on the list of political priorities in the president's first term, despite the issues that it created for enacting his policy agenda, from two ongoing wars to a global financial crisis to health care reform, grappling with the Arab Spring. The second term hasn't been much better. Procurement is not a sexy issue, and it's extremely hard to fix.

As I mentioned, many huge federal contractors have big lobbying shops in which former congressmen and federal CIOs work the halls of Congress and the offices of their former colleagues. It would be utterly unfair to say that all federal contractors are ripping the nation off.

At the same time, it's fair to acknowledge that billions of dollars have been spent on programs that haven't come in on time or don't work. When it comes to national security, this can be particularly egregious. One of the most important whistle-blowers in recent memory, Thomas Drake, ended up going to the Baltimore Sun when no one in government would listen to him crying foul on overspending on a given IT program when a much cheaper option was available.

There are some notable successes to recognize. For instance, the way the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau aligns its technology with its mission is a bright spot in government. I'd like to believe it's possible to reform procurement without completely starting over, if only because that's not an option for federal agencies. The problem is that here, we're talking about real money and real power. Entrenched players have genuine reasons to fight change, from the systems integrators to the big enterprise IT companies that Vivek Kundra memorably called as "IT cartel" as he left office.

The Obama administration, perhaps ironically, has made several other important steps toward this much-needed change, from introducing Presidential Innovation Fellows to bringing in entrepreneurs-in-residence. Indeed, the Department of Health and Human Services' young chief technology officer, Bryan Sivak, has been pushing for many of these changes throughout his career in government. The part of Healthcare.gov that he was responsible for — the front end — was built using agile development, open source, and open standards, working in the open on GitHub with a small D.C. startup. Notably, that part of the site has worked in the midst of all the challenges that the site has had over the past two weeks. The rest of the site, built by CGI Federal, QSSI, and a dozen other contractors, was, by contrast, business as normal. As The New York Times documented Sunday in a well-reported feature on issues at Healthcare.gov, political decisions drove deadlines and the inability of government officials to say that it was not ready for prime time.

The sad truth is that unless we reform how government buys, builds, and maintains information technology, we will continue to get more Healthcare.govs. They'll be built at regulatory agencies, scientific agencies, or places like HUD or the Department of Education or nameless federal agencies that most people don't know exist, along with higher-profile ailing IT projects at the Department of State. Federal IT may be too big to succeed.

I have no doubt that this debacle is incredibly embarrassing for the president and his administration. It's given huge political ammunition to the opponents of the Affordable Care Act and unfortunately further damaged the trust and the government's ability to accomplish big things throughout the country. It's not clear if the tech will be able to be fixed in time for the second stage of people rushing to get insurance before the deadline.

It would be a historic irony if an administration that was elected using cutting-edge technology applied in innovative ways could not carry that innovation into office in support of Obama's signature legislative accomplishment. Unfortunately, unless something changes quickly, that's how this rough draft of history will be coded.