The day after a viral BuzzFeed post asked about the color of a certain striped cocktail dress, neuroscientist Pascal Wallisch pulled up the infamous photo on his laptop and showed it to his wife.

Why are people freaking out about this, he asked her, when it’s so obviously white and gold?

“And she said, ‘What are you talking about? It’s obviously black and blue,’” Wallisch, a clinical assistant professor of psychology at New York University, told BuzzFeed News. “I knew she wouldn’t screw with me — she’s very serious, she’s a lawyer. So I realized immediately that nothing that we know about color vision could explain this.”

Tens of millions of people were having the same argument, leading to a cultural phenomenon now known as simply “The Dress.” In the two years since, at least half a dozen studies have come out trying to answer the question on everyone’s minds: How could two people look at the same photo — on the same screen, at the same time — and have such dramatically different perceptions?

This research has coalesced on an intriguing explanation: The color you see on the dress depends on the unconscious assumptions your brain makes about the light shining on it. People who assume that the dress is in shadow — that is, basking in blue light — will usually see it as yellow, presumably because their brains are subconsciously subtracting blue from the scene to take the shadow into account. Conversely, people whose brains assume the dress is under artificial lights are more likely to see it as blue, because they’re mentally discounting yellow.

But why do certain people make one assumption and not the other?

No one knows exactly, but Wallisch provides one answer in a study published earlier this year. Surveying more than 13,000 people — the largest published study of The Dress to date — he finds that early risers tend to see the frock as gold and white, whereas night owls are slightly more likely to see it as blue and black.

This makes sense, he says, because people who wake up early are, over their lifetimes, exposed to more blue light (from the sky) than are people who tend to stay up into the night, surrounded by artificial yellow light.

For these scientists who have studied The Dress, the photo has profound implications.

“What I find fascinating is that it’s basically some kind of belief or knowledge that people have about the scene that influences what they see,” said Christoph Witzel, a vision scientist at the Justus Liebig University of Giessen in Germany who published a study about the illumination of The Dress this year. “It means that very fundamental things such as colors, that we think are just there, that we believe are parts of the outside world, in reality can be influenced by what we believe.”

For about a month after The Dress appeared, Wallisch said, it was all he and his colleagues could talk about. It was (and still is) one of the only images known to produce such striking differences in color perception from one person to another. “It was like finding a new organ, or a new species,” he said.

“It was like finding a new organ, or a new species."

The dress effect is probably not inherited. The genetic testing company 23andMe polled about 25,000 of its customers about how they saw the photo, and found no genes that could predict color perception. Similarly, a study found that identical twins (who share 100% of their DNA) don’t always see the dress the same way, although they are more likely than fraternal twins (who only share about 50% of their DNA) to see it as the same color. That suggests that genes have some influence on how we see The Dress, but that most of the effect is driven by our environment and life experiences.

Wallisch’s paper, published in the Journal of Vision, is based on two internet surveys: one that included 8,084 people a month after The Dress was published, and another that included 5,333 people a year later.

Like previous studies, Wallisch’s found that people who assumed the dress was in shadow were more likely to see it as gold, compared with those who thought it was in artificial light.

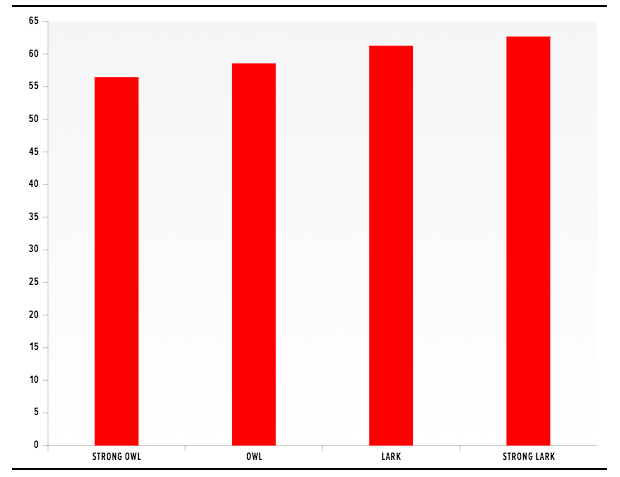

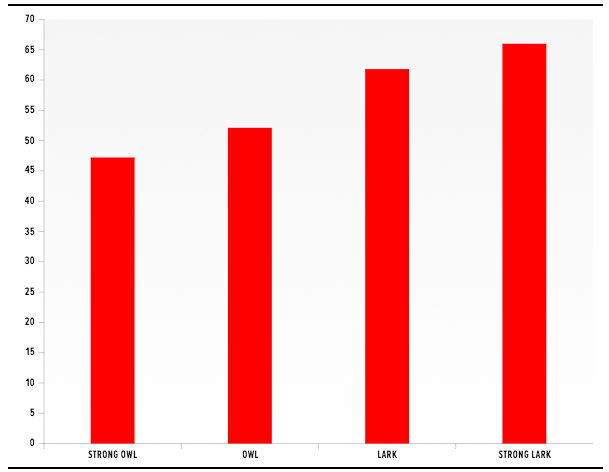

His findings regarding early and late risers (whom he calls “larks” and “owls,” respectively) showed up in both surveys, though the effect was subtle. In the first survey, a “strong lark” was 11% more likely to see the dress as gold and white than was a “strong owl.” (In the second survey, the effect was larger, with strong larks being almost 40% more likely to see it as gold and white. The difference, Wallisch guesses, could be because the first survey, coming out so soon after The Dress, had more trolls lying about what they saw. He did not discard any data points from either survey.)

Original Sample: % of People Who See Gold and White

Replication Sample: % of People Who See Gold and White

The noisy data showed up in his own family: Wallisch is an extreme owl, staying up into all hours of the night, but he saw the dress as gold and white, the opposite of what his paper would predict. And his lawyer wife wakes up early, but saw it as blue and black.

Other researchers found the new study valuable, particularly because its two surveys included large groups of people and replicated each other.

“I don’t very often get to say that studies are impressively well done but I think this one is,” Lisa Feldman Barrett, a professor of psychology at Northeastern University, told BuzzFeed News. “I found it very persuasive.” (As a lark who sees the dress as gold and white, she also happens to fit the theory.)

Feldman Barrett, author of How Emotions Are Made: The Secret Life of the Brain, noted that this is but one example of many in which our brains use the accumulation of past experiences to make judgments about the present. “Everything that you see and hear and taste and touch, every thought that you have, every emotion, every memory, all arises pretty much in the same way — in this predictive architecture of the brain.”

Some scientists aren’t as sold. Dale Purves, a research professor at the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences, told BuzzFeed News that although the new study provides the “definitive database” for data on The Dress, he doesn’t think Wallisch’s theory fully explains the phenomenon. “There’s something deep here, there’s no question,” said Purves (early riser, blue and black). “But it’s fair to say that no one has really explained it.”

Perhaps more interesting than the science of The Dress, Purves said, is the fact that tens of millions of people cared so much about it. “It’s a big deal because of the internet, not the other way around.”