NAIROBI — When Samanthah Maina decided to run for office, the first-time candidate thought she was more than ready. She was prepared to answer questions about her political qualifications, delve into the details of her platform, and ease suspicions of her initial identity as an independent in a political landscape of at least 60 registered parties.

But first the 26-year-old had to campaign door-to-door to collect the 500 signatures she needed to vie for a Members of County Assembly (MCA) seat in the Nairobi neighborhood of Kileleshwa, which found her less prepared to respond to what she was actually asked: “But you’re not married. Are you able to run a ward in public office? Can you be trusted with such responsibility when you can’t run a home?”

Maina, who has since joined the young, progressive Ukweli Party, is well aware that Kenya lags behind other East African countries when it comes to its representation of women in politics. But she still did not expect voters to suggest that she was only vying for the assembly seat — which acts as a link between voters and county lawmakers — in order to sell cosmetics.

“In my head I’m thinking, ‘Why would I choose politics to sell my looks?’” she told BuzzFeed News during an interview at a Nairobi mall cafe on a recent afternoon. “I’ll go for Miss Kenya, right? Not politics.”

She was also taken aback by comments suggesting that her hair, which she often wears natural, looked “unprofessional” and not politician-like.

And she certainly had not braced herself for those who told her that she could get raped simply by running for public office.

“Some people will just put these things before you,” she said. “You’re here trying to sell your manifesto, or the agendas that you have once elected, but then all these other issues are brought up.”

As Kenyans prepare to vote in their general election on Aug. 8, increasingly heated political conversations tend to revolve around one of two topics: Whether or not the elections will result in the same kind of rioting, violence, and displacement that followed the deeply controversial 2007 cycle, and the continued lack of representation of Kenyan women in parliament.

Despite its high rates of economic growth, technological advances, and status as a democratic exemplar among other African countries, Kenya struggles to achieve a gender-balanced government, even as neighboring countries make strides. In Rwanda, for example, women make up 64% of parliament, according to a study conducted by the World Bank. In Uganda, 30% of political seats are held by women. But in Kenya, only roughly 20% of parliament is composed of women, placing it alongside the US in terms of gender parity.

Kenya attempted to address this disparity by including an article in its 2010 constitution requiring that women comprise at least one-third of federal lawmakers — but years of stalling on the mandate nearly resulted in a government shutdown in late March this year.

Among the obstacles hindering women from running for public office in Kenya are a lack of funding, concerns over their safety, and, as Maina experienced, outright sexism and harassment while campaigning.

And she is far from the first to be targeted.

When environmental champion and Nobel Peace Prize winner Wangari Maathai ran for president in 1997, local papers printed rumors the day before elections that she had dropped out, which had a negative impact on her votes.

In 2013, one aspirant told Reuters that an opposition party had raided her campaign site and littered it with condoms in an attempt to denigrate her reputation among conservative voters.

And in 2016, Miguna Miguna, a candidate for governor of Nairobi, was caught on a hot mic during a talk show saying that one of his opponents, Esther Passaris, was “so beautiful, everybody wants to rape her.” The talk show was canceled over the leaked video of Miguna’s comments, but he is still in the running for the governorship.

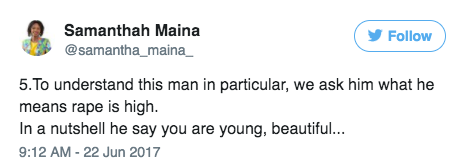

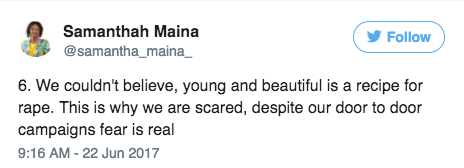

Maina took to Twitter after her experiences on the campaign trail in late June to bring attention to the issue. She cited constituents who told her and her campaign members that “rape incidences are rampant,” particularly because of her youth and appearance.

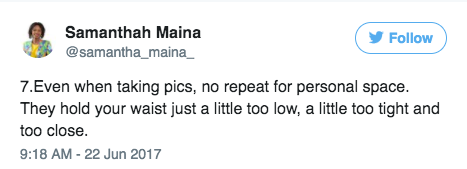

She also called out people who did not respect her personal space when she posed for photos. “They hold your waist a little too low, a little too tight and too close,” she tweeted.

When someone suggested that Maina and other female candidates hire bodyguards to protect them on the campaign trail — and many have in the past — she said that a “mental shift” in society was needed in order to fully bring an end to discrimination.

Obstacles to access exist even for women who are not actively running but simply wish to participate in politics in Kenya.

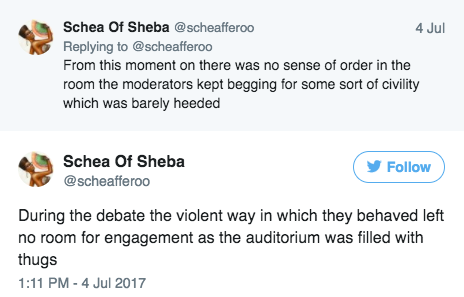

Scheaffer Okore, an activist and vice-chair of the Ukweli Party, attended Nairobi’s gubernatorial debate on July 3 and tweeted the next day about how the complicity in allowing men to get rowdy in the audience sent a message that women were not welcome.

Okore told BuzzFeed News that several of the men in the audience took advantage of the moderator, who was a woman, by raising their hands to ask a question, and rather than return the microphone to her, passed it instead among themselves, rendering her nearly invisible.

In addition to addressing what she called the “toxic masculinity that exists in the political space in Kenya,” Okore said that security institutions prioritizing the protection of women was crucial.

“Women have lived their entire lives learning how to be safe from men," she said. "They should not have to do it in a field where they know it’s male-dominated."

Despite the difficulties, Maina would still encourage other young women to run for office. They just have to know what they’re up against.

“It will test you on every front: emotionally, psychologically," she said. "You might lose weight, or gain weight from the stress. We talk about representation, but we can’t shy away because it’s going to be a bit tough. There’s not going to be a perfect time.”