JOHANNESBURG, South Africa — Yolanda Dyantyi was supposed to be the first person in her family to earn a college degree — and at one of South Africa’s top-ranked universities, at that.

She was 19 years old and ambitious, double-majoring in political philosophy and international relations, and drama. A self-proclaimed feminist, Dyantyi always considered herself an outspoken person, and she got involved in a number of social justice organizations at school. But within two years, Dyantyi was charged with kidnapping and assault by university authorities, and was handed a lifetime ban from studying there; she can’t even set foot on campus. All because of the work she and other student activists were doing to combat rape culture on campus.

Dyantyi and a group of other student leaders started a hashtag called #Chapter212, which references the section in South Africa’s postapartheid constitution that guarantees everyone the right to full control over their bodies. Dyantyi knew firsthand how important it was to protect that constitutional right — during her first year at Rhodes University, she was raped by two male students. She and other student activists knew that sexual assault was prevalent at Rhodes, and used their hashtag to call out the fact that in addition to the trauma of potentially having to sit next to their alleged attackers in class, sexual assault also violated their constitutional rights. She wanted the university to take victims’ claims more seriously, to stop using language that could discourage them from pressing charges — like mentioning how a sexual assault accusation could hurt the perpetrator’s reputation — and to make psychological support services more accessible to victims.

Dyantyi and the group hung posters about rape culture around school — but shortly after, someone tore them down. After that, a post appeared on a Rhodes student Facebook group page naming 11 male students who had been accused of sexual assault by their fellow classmates. It quickly became known as the “RU Reference List.” The list predated the #MeToo movement, which saw women share their stories as victims of sexual harassment and assault 11 years after the term was first coined by Tarana Burke, and the Shitty Media Men list by a year and a half.

“The list didn’t even say they were rapists,” Dyantyi said, “but it was enough to mobilize people.”

The list went viral on campus, and the events that unfolded the day it was posted differ, depending on whom you ask.

According to Dyantyi, a group of women confronted some of the men named on the list outside of their dorm, including a female student who had accused one of the men of raping her. “None of the men were physically harmed,” said Dyantyi, who was present when the man accused of rape was confronted. She described the moment as “a space of healing” for the victim, and denied that anyone in the group was violent toward the male students named on the list. Nothing else happened, Dyantyi said.

The size of the anti-rape protests exploded the next night. Dyantyi remembered the campus being flooded with more than a thousand protesters, a sizable portion of a school with a student body population of about 8,000 people.

Dyantyi acknowledges that she was one of the more vocal protesters during that time. But even though she was one of hundreds of students who took part in demonstrations like a topless protest, she and another female student were the only people that university authorities took action against.

In a disciplinary hearing, two of the men who were confronted said that on the night the confrontation took place, four of the men on the RU Reference List had been dragged out of their dorms, held against their will, and assaulted. Dyantyi’s version of events — that the men were simply confronted and no violence took place — was not recorded during the disciplinary hearing. And so, she said, their version became the undisputed narrative of what happened.

In November 2017 the two women were found guilty of kidnapping, assault, defamation, and insubordination in the university disciplinary hearing, and subsequently banned from Rhodes for life. Rhodes maintains that Dyantyi was not banned because she was protesting. This is all reflected on Dyantyi’s academic transcript, which she said has made it virtually impossible to apply to other schools; nobody wanted to be associated with that.

Now, at 22, Dyantyi is out of school and unemployed.

“The institution criminalized me,” she told BuzzFeed News from a rooftop café in Johannesburg last week.

In August 2018, two years after the RU Reference List went viral, a 23-year-old student named Khensani Maseko killed herself at Rhodes University, weeks after she reported having been raped by a fellow student at the school, which contacted her family and said it would follow up on the investigation, according to a statement. The day she died, Maseko posted her birthdate on her Instagram page with the caption “Nobody deserves to be raped.”

Three days after Maseko died, Rhodes announced that it had suspended the male student she accused of raping her.

Violence against women in South Africa, particularly sexual violence, has been widespread for years, just like in many other countries. For years, the country hailed for its progressive constitution and spirit of activism during the fight for freedom from apartheid has also had some of the highest rates of rape in the world, according to a Statistics South Africa report published last year on crimes committed against women. The same report also found that 3.8% of black men, 2.6% of white women, and 2.5% of black women thought it was OK for a man to hit a woman.

Thanks to the work of Dyantyi and hundreds of other activists fighting to shed light on the crisis of gender-based violence (GBV) in South Africa, elected officials are paying more attention to it now than ever before. But advocates still worry that it may not be enough. The country is holding elections on Wednesday, and some activists say the plight of sexual violence against women has been exploited for political points throughout campaign season. They worry that even though each of the three main political parties has promised to focus on GBV in their manifestos, the problem will be forgotten yet again as soon as the polls close.

Those who have been part of this conversation, both among their respective organizations and with officials, have told BuzzFeed News that while the government is good at giving the appearance of acting on an issue, it routinely fails to deliver tangible results.

That’s part of the reason Zukiswa White, a community organizer, decided it was time to call politicians out for their “all talk, no action” approach to GBV. She’s the spokesperson of Shayisfuba, a growing national campaign focused on building a feminist government. Women represent 42% of the seats in South Africa’s outgoing Parliament, but White said that “women are simply not a political priority in this country.”

The 26-year-old told BuzzFeed News over a chai latte outside a mall in Johannesburg that Shayisfuba — founded last November — brings together women-centered groups from all across the country into a single collective that pushes an openly feminist agenda. That includes the struggle for land, part of a long-held debate about how best to give justice to black South Africans who lost 87% of the nation’s land to white farmers during apartheid.

On May 1, Shayisfuba held a meeting in Soweto, a township known for the anti-apartheid protests that took place during the 1970s and ’80s. About 270 people showed up, mostly women, clad in gray T-shirts with a message on the back that read: “We demand a feminist government.” The group invited speakers to discuss issues ranging from the poor delivery of basic public services like water, electricity, and sanitation to the need to recognize and protect members of the LGBT community. Breaks between sessions featured Ariana Grande’s “God Is a Woman,” and a musical performance by a local rapper.

In the afternoon, three high school students took to the stage and talked about the difficulties they face getting home from school. Cab drivers in the area are known for harassing young women, making comments about their school uniforms, pressuring them to sit in the front seat beside them, offering them money for sex, and sometimes raping them.

Sitting in the audience was a cab driver who’d been invited to the meeting by one of the organizers. After listening to the girls’ testimony, he stood and told the audience that he’d seen multiple instances of the harassment they described while on the job.

“We men need to do better,” he said.

South Africa has had no shortage of high-profile cases of physical and sexual assault of women in recent years. In March, a woman named Gugu Ncube’s seminude protest in front of the Union Buildings in Pretoria — the seat of the South African government and home to the office of the president — went viral on social media. Wearing her underwear and a piece of cloth covering her chest, Ncube, who alleged that her former boss at the University of South Africa had sexually harassed her, demanded to see President Cyril Ramaphosa. She was arrested by a squad of women police officers and charged with public indecency. Ncube declined to speak to BuzzFeed News.

In 2017, Mduduzi Manana, then the deputy minister for higher education and training, pleaded guilty to three counts of assault against three women he got into an argument with at a Johannesburg nightclub. Last year, Manana’s housekeeper accused him of pushing her down the stairs in his home, which he denied. He was not prosecuted for the allegations. In August 2018, he spoke at a fundraising gala for GBV called “Legends United Against Gender-Based Violence.”

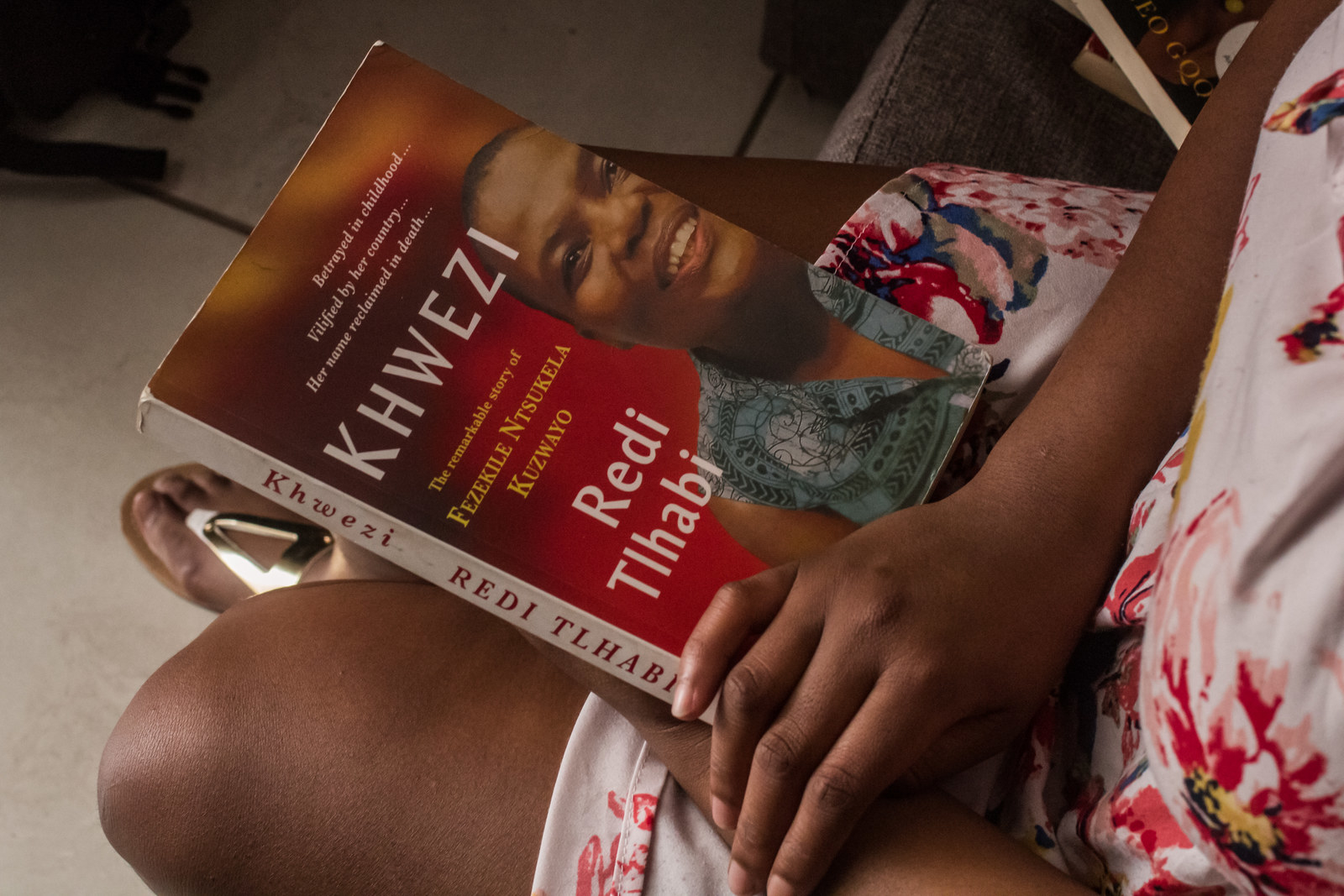

One of the most widely covered cases took place in December 2005, when a woman named Fezekile Kuzwayo accused Jacob Zuma — then the deputy president, but he would later go on to become president — of rape. The controversial case saw Zuma supporters burn images of Kuzwayo (a well-known AIDS activist who was HIV-positive, and who died in October 2016) and call her a bitch. While being cross-examined in court, Zuma infamously claimed that taking a shower after having sex with someone who is HIV-positive would reduce his risk of contracting the virus. The court dropped the case, and a judge ruled that Zuma and Kuzwayo had consensual sex. Nearly 14 years after Zuma’s trial, the African National Congress — the party he belongs to, and the same party that has governed the country since apartheid — still does not have an internal policy for handling sexual harassment.

Much of the discussion around GBV that’s happening in South Africa now is the result of #TotalShutdown, a nationwide protest against GBV that nearly brought the country to a standstill last August. It signaled a major shift in the level of public anger among many South African women and gender-nonconforming people, and its members have continued to challenge the government to play a more active role in bringing a stop to it.

Mandisa Khanyile was on the national team of the #TotalShutdown, and was responsible for bringing together GBV organizations, student groups, and trade unions for the movement, and told BuzzFeed News during the country’s first public hearing on GBV, hosted by the Department of Women, that she and 13 others had created a Facebook group aimed at forcing the government to pay attention to GBV. In just a few weeks, it grew to 50,000 members.

“Women in this country have been dying,” said Khanyile, 36, who currently directs an organization called Rise Up Against GBV. “Absolutely nothing is getting done about it. We’ve had campaigns — so we thought, why don’t we shut the country down to show them how powerful we are? It’s 52% of the population who are dying and nothing’s being quoted about the fact that there’s a femicide in South Africa.”

The organization initially only planned to march in South Africa's three capitals — Cape Town, Bloemfontein, and Pretoria — on Aug. 1, but Khanyile said that there was so much outcry from women in provinces and cities outside of the capitals, they realized it needed to be a nationwide shutdown. President Ramaphosa had no choice but to listen to them.

By the end of October, Ramaphosa had announced the National Summit Against Gender-Based Violence and Femicide, which was one of the #TotalShutdown movement’s 24 demands. Survivors of GBV spoke. The summit organizers created commissions focused on a range of issues, from preventing violence against women to figuring out how best to support survivors.

But, as Khanyile said, “South Africans are great at paperwork. No one can out-paperwork us. We will show you the best, most beautiful policies, the most stellar constitution. We will out-paperwork you any day. Implementation is the issue.”

As if to underscore the problem, two weeks before the elections, the Department of Women hosted the nation’s first public hearing for GBV. The event was supposed to feature testimonies from survivors of different types of crimes ranging from domestic violence and femicide to the assault of older people and members of the LGBT community. The intention, according to the department’s press release, was to “allow society to gather and collectively shed the veil of shame, reduce notions of abandonment, and to offer support to victims and survivors of GBV.”

But the hearing, which took place at a modestly sized stadium in a town 30 minutes outside of Pretoria, started three hours late. The schedule, as a result, had to be modified, and the survivors did not end up having a chance to share their testimonies. And when it did finally start, one of the women panelists said, while addressing the men in the room with an opening prayer, “Men, you are the head of the house.”

The paradox of hearing traditional and potentially dangerous gender roles reinforced at a state-sponsored gathering about GBV is South Africa’s struggle to address the issue in a nutshell.

The ANC, nonetheless, outlined a plan in its party manifesto to address GBV, which it acknowledged had reached “crisis proportions.” In addition to accelerating educational training for young people to “change social attitudes” and creating harsher sentencing for perpetrators of domestic and sexual violence, the ANC vowed to better equip the police and members of the court to support victims and survivors.

Other parties have not ignored the issue either. The Economic Freedom Fighters party (EFF) specifically focused on violence committed against black African women in its manifesto, noting that “while patriarchy and sexism are pervasive in our society, it is black women who suffer the most from gender-based violence.” The party aimed to address the problem by incorporating women’s liberation into its larger fight for economic freedom for black people.

And the Democratic Alliance, the main opposition party to the ANC, wanted to “scrap the ineffective and toothless Ministry for Women under the Presidency.” According to its manifesto, the DA wants to reallocate those funds to the Commission for Gender Equality, which was formed out of a constitutional mandate, and the National Council on Gender-Based Violence, launched by former deputy president Kgalema Motlanthe in 2012 (but which dissolved in 2014, and was reestablished at Ramaphosa’s Gender Summit). The manifesto also included specific protections for members of the LGBT community.

But even larger organizations working on gender equity remain skeptical of the parties’ seriousness about GBV. In February, the Commission for Gender Equality invited top-level members from each of the three major parties to a meeting about the representation of women in politics and the elections. And while each party showed up to the gathering, they all sent lower-ranking members who were not in decision-making roles, according to the commission’s chair.

The discrepancy between the measures the government has taken to listen to #TotalShutdown activists, and the strategies it has employed to actively decrease the rates of violence against women were evident at the public hearing in Pretoria.

For example, the Department of Women created a system for detecting and responding to possible GBV with what it calls the “GBV Robot” for women. (“Robot” is the word many South Africans use for stoplight.)

The “green light,” associated with the hashtag #Lights4Life, describes a healthy relationship (romantic or platonic) of mutual respect and safety. The “yellow light,” or #SeeTheSigns, describes the typical early signs of abuse, like manipulation or public humiliation. The “red light” is called #Run4YourLife; the first bullet point reads: “Your partner threatens to kill you or your children.”

Khanyile, the #TotalShutdown activist, took issue with the system, and condemned “the whole idea that it’s the survivor or the victim who needs to see the signs and run, instead of actually focusing on the perpetrator and the role that they should take in ending GBV.”

She also noticed a fair amount of what she saw as victim-blaming at the hearing. The host of the event, a former radio host who has herself spoken about her experiences with domestic violence, said to women during her opening remarks, “If you get beaten once, you’re a victim. If you get beaten twice, you’re a volunteer.”

As a #TotalShutdown volunteer who also sits on the newly formed national GBV council, Sibongile Mthembu often acts as a liaison between the two groups. Like Dyantyi, the former Rhodes student who was banned, Mthembu, 51, is also invested in the cause for personal reasons: When she was 28 years old, her partner stabbed her more than 100 times in a single incident.

She told BuzzFeed News in the parking lot of the public hearing — she divides her time between South Africa and Mozambique, where she works, and was headed to the airport — that working with the government has not always been easy.

Mthembu said she bristled at the suggestion that anyone would volunteer to be abused, and almost brought it up when it was her turn to speak on the panel, but then thought, referring to the host, “Why should I be correcting her? She needs to own up to her mistakes. I’m tired of correcting women.”

She also acknowledged that she’s heard problematic statements even within activist circles.

“Remember, it’s not only the outsiders,” she said. “I’ve found women’s spaces are very toxic because we’ve been abused, we are broken, and we haven’t dealt with the anger.”

Dyantyi, the student activist, still participates in the various feminist movements trying to end GBV in South Africa. She has since decided to shift her focus solely to the victims of GBV, and is in the process of creating a website for victims to archive their stories in the hopes that sharing their experiences will help them heal.

“It’s tiring sitting in meetings with the government when they don’t want to recognize that GBV is a national crisis, but we can’t keep protesting the same shit,” she said.

But Dyantyi, like several other organizers working on limited resources, oftentimes without pay in the fight against GBV, is drained. And not only does she not see an end to the battle anytime soon, regardless of how elections turn out — she can’t imagine herself doing anything else.

“I’m scared for our country, but how can you not be in fight mode when your life is at risk every day?”●